Key findings and recommendations

Data collection and information reporting

Reported incidents

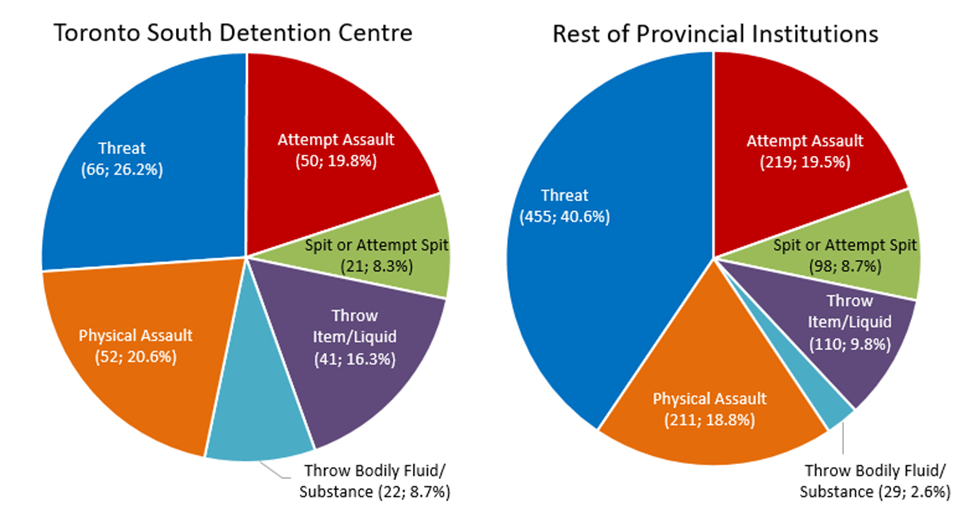

The Independent Review Team analyzed ministry data and found that the largest number of reported inmate-on-staff incidents across all provincial institutions in 2017 was attributable to threats, followed by attempted assaults and physical assaults.

Figure 2. Reported inmate-on-staff incidents by type, 2017 at TSDC and rest of provincial institutions

It is clear that a province-wide analysis of incidents of inmate-on-staff violence is ineffective at identifying the specific issue(s) experienced by a particular institution. Local analyses are necessary to understand the type, frequency, and severity of incidents that occur at specific institutions in order to tailor a localized operational response that mitigates the risk of future incidents.

Reporting process

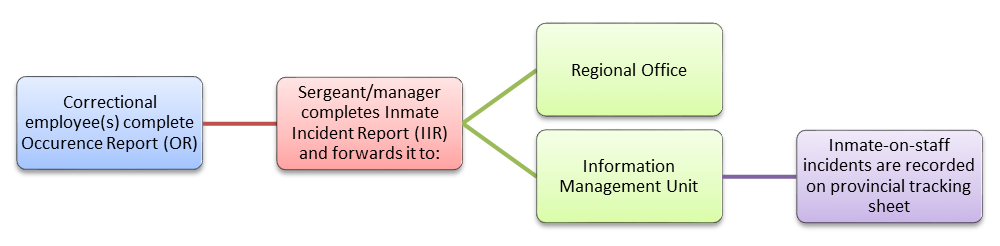

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services’ (MCSCS) current policy mandates that incidents of workplace violence must be reported by the employee to a manager or supervisor either verbally or in writing.

Figure 3. MCSCS incident reporting paperwork process

The Independent Review Team previously reported that the IMU database that records inmate- on-staff incidents is outdated and that this precluded efforts to conduct any high-level analyses.

Implementation of a more robust, efficient, and digital infrastructure for data relating to institutional violence is essential to identify any patterns that can inform quality decision- making and policy changes that impact institutional operations and standing orders. In addition, the TSDC Case Study identified many instances of locally tracked inmate-on-staff occurrences that were not reported to the IMU by sergeants on IIRs, and thus were never considered for inclusion in the ministry’s list of inmate-on-staff incidents. It is unknown whether this issue is unique to TSDC or if similar patterns would emerge at other provincial institutions. It is necessary to ensure that sergeants and other managers are adequately trained in completing the IIRs in this new digital platform. Furthermore, it is essential that the ministry standardize the process for selecting when ORs can simply be filed for local records retention purposes, and when, and how, ORs become IIRs that are forwarded to the regional offices and IMU.

The TSDC Case Study also revealed that there is no consistency in terms of how correctional employees involved in incidents are identified on IIRs. Current, there is no ministry policy that identifies a requirement for involved correctional staff beyond direct victims of reported assaults to be named on IIRs;

In addition to IIRs, the Independent Review Team identified data entry errors and/or inconsistencies regarding misconduct dispositions in the Interim Report and further investigated these concerns.

Information sharing

The Interim Report underscored the current lack of communication between the ministry’s corporate offices and institutions due to the aforementioned absence of trend analyses regarding reported incidents of violence at corporate and institutional levels.

Presently, OTIS is available as a ministry-wide database holding pertinent information regarding any individual who has ever been supervised by MCSCS in the community or in one of Ontario’s provincial institutions. As previously noted, OTIS can only be an effective tool for information sharing if the information entered is reliable. Incomplete and/or unverified information (e.g., missing disposition information; active alerts

The digital inmate incident reporting platform under development by the Modernization Division should allow for data to be extracted and analyzed on a number of variables, including allowing for institution-specific analysis. This would be a useful tool for institutions and would foster better understanding of incident-related trends at local sites, at comparable institutions (e.g., similar size or inmate demographics), and across the province.

Data collection and information reporting recommendations:

-

-

I recommend that the ministry’s data collection practices as they relate to institutional violence be restructured to facilitate the creation of targeted and timely policy responses.

Consultation with the Information Management Unit, institutional staff, and data analysts must occur to ensure that any new platform created captures necessary information for present and future analysis of institutional violence. At a minimum, the new platform must capture multiple variables including, but not limited to, specific inmate populations, correctional employees, time and location of incidents, and institutions or regions of the province in order to identify patterns relating to institutional violence that may emerge.

-

I recommend that the ministry conduct a detailed analysis of violence in each of Ontario’s correctional institutions. The methodology used in the Case Study: Toronto South Detention Centre should serve as a template for a preliminary localized analysis at each correctional site.

This will ensure that variation between institutions due to inmate demographics, staff complement, and supervision culture and practices, among other factors, are given appropriate consideration. Methodology will need to be expanded to include other aspects of institutional violence, including inmate-on-inmate, staff-on-inmate, and staff-on-staff violence.

-

I recommend that the monitoring of reported incidents of institutional violence be in regular time intervals, and as close to real-time as possible, to allow trend analysis that quickly recognizes developments or anomalies.

The Correctional Services and Reintegration Act, 2018 creates an Inspector General role for continuous oversight of Ontario’s correctional institutions; monitoring institutional violence must be a key responsibility allocated to this office.

-

I recommend that correctional managers and senior administrators conduct routine audits of reported incidents of institutional violence and their corresponding paperwork to ensure compliance with ministry policy and law. Timely completion of these audits should become a performance consideration.

-

I recommend that the ministry create a new policy standardizing when and how to initiate an Inmate Incident Report following the completion of an Occurrence Report by a correctional employee.

-

I recommend that sergeants and managers are trained on the utilization of the Modernization Division’s new digital platform for incident reporting, including the policy direction following the implementation of recommendation 1.5. from the Independent Review of Ontario Corrections’ Institutional Violence in Ontario: Final Report. This training must be completed prior to the rollout of the new platform.

-

I recommend that data from the Offender Tracking Information System and the Modernization Division’s new digital Inmate Incident Report platform be integrated to allow for multi-variable analysis relevant to institutional violence.

-

I recommend that data and trends pertaining to reported incidents of violence are regularly monitored at the institutional, regional, and corporate levels within the ministry.

Until the Inspector General of Correctional Services is established, trends must be analyzed within MCSCS as close to real-time as possible and communicated between corporate, regional, and institutional levels promptly to inform the development of appropriate operational responses.

-

Institutional culture and staffing

Correctional work environment

Characteristics of modern correctional practice include comprehensive correctional care interventions, validated security classification, and evidence-based risk management. Within this environment, correctional officers find themselves working at the intersection of care and custody, negotiating the tensions between rehabilitation and security as well as assuming the role of ‘peacekeeper’

We need to understand and recognize what didn't work and what is not working today in order to move forward. Not only do staff need to be safe, they need to work smart and sometimes common-sense goes a long way. We need leaders who are experienced and know the business. If not they will not be respected by the Inmates or the front line staff. I will reiterate not only do the staff need to feel safe the inmates need to feel safe as well. You can't make positive change when inmates are in fear of the predatory element among its population.

Senior Administrator, Eastern Region

While it is the case that some inmates can be violent – and should be classified and housed as such – it is ultimately difficult to perfectly predict instances of violence in correctional settings. Research on strategies for reducing institutional violence refute claims that it is dependent on the degree of dangerousness of inmate populations, rather, it is a “direct product of prison conditions and how [government authorities] operate [their] prisons.”

We are dealing with people and should not be warehousing them. […] Many individuals should not even be incarcerated. There should be more assisted living/social intervention prior to even coming into custody.

Sergeant, South West Detention Centre

The Independent Review Team’s findings on institutional violence flow directly from engagement with frontline staff, managers, and senior administrators, who provided a candid glimpse into correctional work culture. Much of the feedback from correctional employees revealed deeply held concerns by frontline staff regarding their working environments, relationships with management, training, professional development, and mentorship opportunities for new staff. Feedback provided to the Independent Review Team identified occupational stress associated with employee safety concerns as well as the lack of recognition by management as having a negative impact on correctional officers’ perception of their jobs and further widening discontent with upper management.

Working with managers who are incompetent and make poor decisions with disregard for staff safety makes for a stressful work environment.

Correctional Officer, Maplehurst Correctional Complex

Daily worries about job safety, dangerousness, and fear has been shown to contribute to an increase in occupational stress and “negative job satisfaction” for correctional officers.

I am happy that I am coming to an end of my career with 20 shifts left to work before retirement. I will miss my life long [sic] career but will be pleased to be free of the day-to-day stress that it brings […] My suggestion to you going into the future is help with the day to day stress. […] just responding [to a code] is a "stressor" for many staff.

Concerns regarding safety varied considerably by position. Of correctional officer respondents, 53%

Respondents were also asked if and how often they worried about being assaulted by an inmate (see Appendix B, Tables B-2 and B-3). Of correctional officers, 44% reported that they worried about being assaulted once a day and an additional 22% worried at least once a week.

Crisis in Corrections is an orchestrated tempest in a teapot. Hopefully this fools no one.

Sergeant, Northern Region

Only 13% of correctional officer respondents indicated that they never worried about being assaulted by an inmate. In contrast, only 27% of respondents in all other employment positions indicated that they worried about being assaulted by an inmate at least once a week, and nearly half (44%) of those respondents indicated that they never worried about being assaulted. This variation in responses among different positions is of particular interest considering that many of the employees who are not correctional officers, such as sergeants and programs and health care staff, also have frequent direct contact with inmates.

Relationships with managers

Research on correctional staff culture in Canadian jurisdictions has documented a significant concern with staff-management relationships,

I have only been employed a little over 2 years. I already have a strong distrust of management. I felt this distrust when I had one year in. I feel management doesn't work with frontline staff, with hold [sic] information, and try and get new staff to do things they shouldn't but they don't know any better.

Correctional Officer, Maplehurst Correctional Complex

In written responses, many correctional officers directly or indirectly referred to a disconnection between management and frontline staff. For instance, one correctional officer commented, “staff morale is at an all-time low […] We need upper management that cares about the staff, actually takes the time to talk to the staff, even introducing themselves!!” One sergeant echoed this sentiment, “due to the lack of support from senior management as well as the lack of transparency, equality, and fairness the staff moral [sic] is low. In this institution[,] opportunities are given to people who are in cliques and not because they know the job or are familiar with the area.”

Any ministry efforts to mitigate institutional violence must consider how the frontline staff- management relationship functions in correctional facilities in Ontario. As noted in the Interim Report, the lines of communication – whether formally through the chain of command or informally between staff – must be strengthened in order to establish clear directives, expectations, and accountability. In the IROC Institutional Violence Survey, though 58% of correctional officer respondents felt that there was good communication among colleagues, only 13% felt that there was good communication between staff and management at their institution (see Appendix B, Table B-1). Strong standards of communication signal a commitment to transparency in decision making, policy changes, and implementation efforts. Further, moral competency has been shown to be a key requirement of senior administrators and management in organizations that emphasize “strong moral identity” in employee directives and policies.

Perspectives and attitudes toward correctional work

A common theme that emerged from correctional officers’ responses to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey was a general punitive and discipline-oriented philosophy. Written responses to the survey often highlighted ongoing grievances about violent inmates in correctional institutions across Ontario and depicted them as unpredictable, insubordinate, and dangerous. Correctional officers identified recent ministry efforts to reform segregation and use of force policies and increasingly violent inmate populations as contributing to the rise of reported incidents of violence. To gain a sense of correctional officers’ perspectives and attitudes towards their role and correctional work broadly, the IROC Institutional Violence Survey prompted respondents with questions examining their interactions with inmates, the purpose of corrections, and perspectives on power (Table 2).

Our ability to physically discipline Inmates has been taken away […] Murderers, Rapists, Pedophiles, Child Pornographers, ISIS Terrorists, Blood and Crip Gang Bangers [don’t] deserve more human rights than the general public and the Correctional staff that watch over them.

Correctional Officer, Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre

| Statement | Agree or strongly agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree or strongly disagree | No answer | Not applicable | Total responses to question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have a good relationship with individuals in custody in my current institution. | 499 (54.96%) |

294 (32.38%) |

94 (10.35%) |

12 (1.32%) |

9 (0.99%) |

908 |

| The purpose of incarceration is rehabilitation and eventual reintegration. | 496 (54.63%) |

189 (20.81%) |

205 (22.58%) |

16 (1.76%) |

2 (0.22%) |

908 |

| Friendly relationships with individuals in custody undermine staff authority. | 248 (27.34%) |

287 (31.64%) |

362 (39.91%) |

8 (0.88%) |

2 (0.22%) |

907 |

| Individuals in custody should be under strict discipline. | 670 (73.87%) |

155 (17.09%) |

80 (8.82%) |

2 (0.22%) |

0 (0.00%) |

907 |

| I try to build trust with individuals in custody. | 689 (76.22%) |

151 (16.70%) |

51 (5.64%) |

9 (1.00%) |

4 (0.44%) |

904 |

| Individuals in custody take advantage of you if you are lenient. | 730 (80.57%) |

120 (13.25%) |

52 (5.74%) |

4 (0.44%) |

0 (0.00%) |

906 |

| Individuals in custody have too much power in my current institution. | 773 (85.32%) |

76 (8.39%) |

54 (5.96%) |

3 (0.33%) |

0 (0.00%) |

906 |

| Staff have too much power in my current institution. | 23 (2.54%) |

58 (6.40%) |

816 (90.07%) |

7 (0.77%) |

2 (0.22%) |

906 |

| I believe that most individuals in custody in my current institution should be in custody. | 644 (70.93%) |

201 (22.14%) |

28 (3.08%) |

29 (3.19%) |

6 (0.66%) |

908 |

| It is important to take an interest in individuals in custody and their problems. | 415 (45.76%) |

302 (33.30%) |

178 (19.63%) |

11 (1.21%) |

1 (0.11%) |

907 |

Written feedback provided further evidence of strong ‘Us vs. Them’ attitudes. For example, one correctional officer noted:

Our "clients" don't seem to mind jail. As a new [correctional officer], I see inmates don't mind spending time here with all of the benefits of jail, better meals than I eat, television, healthcare, yard, supplies, and assaulting a peace officer resulting in no additional jail time - why do they eat delicious meals when the person they killed is dead.

As noted, relationships between correctional staff and inmates can be positively influenced by individualized correctional work environments. Of correctional officers and sergeants (including staff sergeants) surveyed across the ministry, over half (55%) indicated that they had a good relationship with individuals in custody. Moreover, 76% reported that they tried to build trust with individuals in custody throughout their work.

The largest proportion of correctional officer and sergeant (including staff sergeant) respondents (40%) felt that friendly relationships with inmates did not undermine staff authority, though the majority supported the notion that inmates should be under strict discipline (74%) and that inmates “would take advantage of you if you are lenient” (81%). These responses further suggest that while correctional officers and sergeants might perceive that relations can be friendly, friendly relationships are considered as only possible under compliance and discipline regimes.

I was seconded [… to a] maximum security environment [where] I applied the interaction techniques I used at OCI. I also [wore] a name-tag. I found that the offenders responded very well to my positive and respectful attitude and were significantly more open once they saw my name-tag… The Officers I was working with thought I was hilariously kind to offenders… Direct supervision works. But you can’t get jail guards to buy into it.

Correctional Officer, Ontario Correctional Institute

Overall, punitive views prevailed across institutional employees in regard to correctional work. With respect to discipline, 67%

The inmates know that they can assault staff, threaten staff, intimidate staff with no punishment and it is getting worse by the day. The elimination of segregation punitive reasons has been the worst decision made. If your child spit on you would you not take away there [sic] privileges and put them in time out, if they hit another family member would the same thing not happen.

Similar sentiments were previously expressed by staff in the Interim Report, reflective of the lack of coherent and coordinated ministry direction to operationalize the MCSCS 2016 directive on segregation reform.

The punitive views and disciplinary philosophy were also reflected in the responses that correctional employees – and in particular, correctional officers – provided to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey regarding which measures would most increase staff safety at their institution (Appendix B, Table B-5). For instance, the most commonly selected measures from a list of options were: mandatory minimum sentences for assaults on staff (72%

Similarly, a number of correctional staff voiced frustration with the apparent lack of criminal repercussions for inmate-on-staff incidents. For example, one officer noted, “MANY times [incidents] are dealt with in house and the police are not contacted and charges not laid. When they are the charges are thrown out or the sentence is served concurrently so there is zero reprocussions [sic] for assaulting a staff member.” Similarly, a sergeant expressed discontent, noting that:

Penalties and sanctions are way to [sic] lenient. If an individual walked up to a police officer, or for that matter [any] member of the general public and assaulted them that person would receive serious charges. Why when it happens behind facility walls does is it feel like it is more accepted? Police, Crown attorneys and the judiciary seem to feel like it’s part of our job.

Discussions with police services revealed that corrections and police procedures are, at times, in conflict. For example, police indicated that:

When correctional staff respond quickly to a disruptive inmate, they may clear the scene without preserving the integrity of evidence, which hinders police investigations. Consequently, the evidentiary requirements necessary to pursue a criminal charge may not be satisfied. This may contribute to correctional staff’s dissatisfaction with the police response and criminal sanctions following an inmate-on-staff incident.

footnote 66

In consultation with the Independent Advisor, some police expressed favourable attitudes towards implementing dedicated police units responsible for investigating incidents at correctional facilities. These specialized officers would become familiar with correctional settings and develop working relationships with correctional staff. Similarly, correctional employees would have an identified police resource to enhance their understanding of criminal procedure and evidentiary requirements.

A strong belief in discipline was explicitly evident in responses to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey pertaining to use of force. Numerous correctional officers expressed a reliance on use of force as a disciplinary measure. Over one-quarter (26%

As for USE OF FORCES, it is a jail. USE OF FORCES occur for a reason whether it is to stop individuals from causing excessive harm to another or defending an employee from assault. There should not be a ‘bad look’ towards use of forces as they are what keep our institutions in order when it is needed.

The revised Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners – the Mandela Rules – adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, restricts use of force on inmates to cases of self-defence, attempted escape, and active or passive resistance, though force must be “no more than is strictly necessary”.

MCSCS policy also prohibits use of force as punishment, stating that “Force is not intended to be, and must never be used as a means of punishment”

Many inmates understand only one thing - force. Unfortunate as it is - it is a fact. Placating inmates with food and other items for simple things such as leaving a cell, only empowers them to continue the behaviour. It is a simple fact that sometimes minor force must be used. Making staff write reports and forbidding them to handle a misbehaving inmate only makes the staff and the whole system impotent. If the inmates see that there are consequences to misbehaviour then maybe they will learn and not have to come back. But then that is why they are there in the first place.

Some of the responses that the Independent Review Team received from frontline staff expressed concern with the ministry’s investigation and review processes following use of force incidents. For instance, one officer asserted, “[w]e have good officers wanting to give up, not showing up for work, because Ontario corrections have people undermining them… or judging a [person’s] use of force incident without ever being in a use of force” while another affirmed, “officers are now to the point where they hesitate to use force on [an] inmate when it is justified because they fear suspension”. Despite claims that correctional officers were reluctant to use force, and in spite of a declining provincial inmate population, the Independent Review Team found that reported use of force incidents actually increased from 1,249 incidents in 2013 to 2,490 in 2017.

The TSDC Case Study supported these findings as reported use of force incidents at the institution increased between 2014 and 2017.

The Independent Review Team further found that there is a lack of research evaluating the effectiveness of use of force models in correctional settings within Ontario and in other provinces and countries. Both the effectiveness of the use of force training and the current MCSCS Correctional Services’ Use of Force Model in Ontario must be reviewed against evidence-based best correctional practices. The Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) has recently adopted an Engagement and Intervention model to replace their previous use of force model. Though the effectiveness of this new model has not been evaluated, the Office of the Correctional Investigator recognized it as “an important change in officer conduct and, just as importantly, a major shift in culture within CSC”.

Training and hiring correctional staff

The ministry acknowledged that the current Correctional Officer Training and Assessment (COTA) program was outdated and in need of revision,

I feel it would be very useful to frontline staff to receive (any) training on de- escalation techniques. I don’t believe humans are born with the skill level required to defuse the high tension levels that we reach in the jail setting. By the time the crisis negotiator (the only one with any training in this) arrives the situation has already gotten out of hand. Telling us to “use your de-escalation techniques” is not training.

Correctional Officer, Central North Correctional Centre

During preparation of the Interim Report, the Independent Review Team consulted with the Ontario Correctional Services College (OCSC) regarding the current curriculum taught to new recruits in an effort to understand where effort is being concentrated in regard to training and shaping new cohorts of correctional officers. The Independent Review Team was provided with course outlines and student manuals and found that, of the 12 hours dedicated to defensive tactic training, only 90 minutes are dedicated to defusion of hostility whereas 4.5 hours are dedicated to the use of restraints, aerosol weapons, and expandable batons.

If staff could be trained in communication skills more. Staff get 40 hours of use of force training every two years but no communication skills training. Most situations can be diffused [sic] by communication but no training in that field.

Senior Administrator, Northern Region

In response to requests from the Independent Review Team, the ministry’s Modernization Division advised that developments are underway to design a “work integrated learning” model that combines theoretical learning with on-the-job learning components to meet the current needs of correctional officers. The COTA redesign is also to include a mental health component, but little information is available on whether this would include a very necessary component on self-care. At the time of this report, no changes to the COTA curriculum have been implemented. Appropriate communications training, both formally through COTAand informally through local mentorship and job shadowing, has direct implications on operational outcomes including interactions with inmates. The ability to defuse a situation before using physical force is crucial to mitigating institutional violence. In updating the course curriculum, it is crucial to ensure that COTA graduates receive sufficient training in human rights, correctional law, and self-care and resiliency for dealing with workplace stress. Training must be applicable to the day-to-day situations that correctional officers face in their work environments when dealing with inmates.

I feel that the correctional officer training curriculum needs an overhaul to change the way that officers view and treat inmates, particularly those with mental illnesses, which makes up the vast majority of our inmate population.

Senior Administrator, Northern Region

Overwhelmingly, senior administrators told the IROC Institutional Violence Survey that correctional officers lack sufficient training in the areas of conflict de-escalation and communication. One senior administrator from Central Region noted, “[w]e need to hire staff that have the capacity and demonstrated ability to be effective communicators and are [able] to deal and work with conflict.” Another senior administrator offered:

The lack of experience for the new staff being hired and the sheer numbers of new staff leaving gaps in experienced officers working with inmates, and the inability for the ministry to recruit and retain skilled competent managers has lead [sic] to a crisis in succession planning. Ontario has fallen behind in the compensation area and the disparity in the pay scale has driven skilled competent officers away from promotion when they can make more money in their current roles. Their [sic] is a crisis in retaining managers in the workplace creating gaps in supervision and management of officer performance and mentorship.

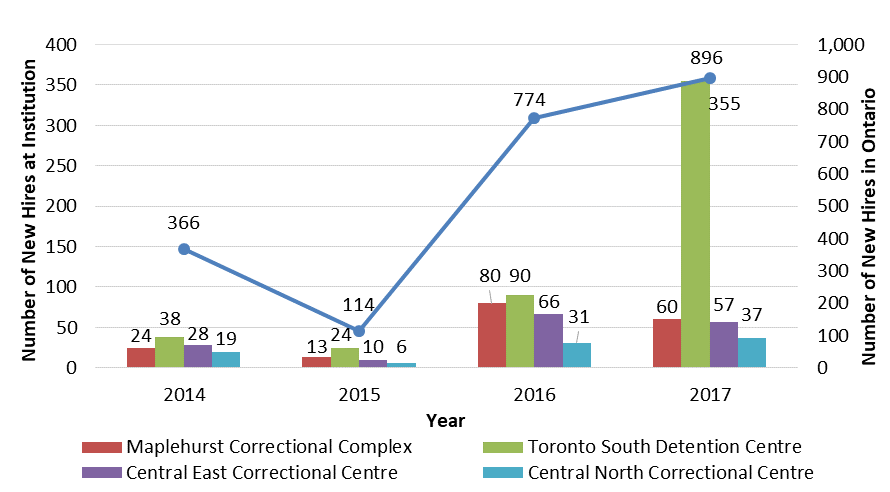

Between 2009 and 2013, there was a moratorium on all correctional officer recruitment. This impacted operations in all of Ontario’s correctional facilities, resulting in staff shortages and deterioration in the conditions of confinement including more time restricted to cell, reduced programming and recreation and an increased number of institutional lockdowns. Once the moratorium was lifted, in 2016, the ministry announced a commitment to hire 2,000 correctional officers over the next three years.

All the new hires in such a short span of time makes for an extremely dangerous workplace due to all the inexperience[d officers] working units with dangerous offenders.

Correctional Officer, Maplehurst Correctional Complex

Figure 4. MCSCS new hires in select Ontario correctional facilities, 2014-2017

Note: new hires includes correctional officers recently graduated from the Correctional Officer Training Assessment (COTA) program, re-hires (former officers who left their positions), and those who transferred form youth corrections following "conversion training".

I am disappointed with the way I was hired and trained. I started when Direct Supervision was a year old and had a slide show and small section of my training binder. I did not see the inside of South West Detention Centre until I arrived on unit for my 2 x 60 hour work weeks of training and my 4 hour orientation my first day. My training binder is still not complete and [it has] been 3 years.

Correctional Officer, South West Detention Centre

Over two-thirds (70%) of all correctional employees who responded to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey selected “experienced staff”, and 43% selected “staff training”, as key elements that contribute to staff safety in their institution.

These days staff are being hired by the dozens, unfortunately are not getting the one-on-one assistance from the more experienced staff. Therefore, the new staff are training the newer staff, so much is lost in why we do things a certain way. New staff are fearful because they haven’t learned how to build a respectful relationship with clients. Mentorship is important, and communication is essential.

To provide support to both institutional managers and frontline officers, the introduction of a correctional officer position in a senior or supervisory role could offer skilled and motivated staff with developmental incentives and meet the current need for peer mentorship. At present, the ministry utilizes two correctional officer classifications: Correctional Officer 1 and Correctional Officer 2. All new correctional officer hires begin their employment with the ministry as Correctional Officer 1 and “based on accumulated hours and satisfactory job performance they can eventually progress to Correctional Officer 2 classification.”

Staff are not trained appropriately or supported to deal with mental health inmates. There should be special hand-selected/hired staff to handle mental health inmates as they do not fit the role of traditional Correctional Officer and did not necessarily sign up for that role or understand how to deal with it. There also needs to be a way to effectively weed out correctional officers that are problematic working with inmates.

Sergeant, South West Detention Centre

Institutional culture and staffing recommendations:

-

-

I recommend that the ministry develop a comprehensive staff mental health strategy to provide self-assessment, self-care, and external support for correctional employees to assist in coping with occupational stress and injuries.

-

I recommend that the ministry develop a management model with a care-based, ethical, and empathetic decision-making framework for daily interactions with frontline staff that will positively impact staff-inmate interactions, improve officer wellness, as well as enhance institutional safety and security.

-

I recommend that the ministry conduct annual “quality of environment” or “moral performance” audits of all correctional institutions benchmarked against international and evidence-based best practices.

-

I recommend that the ministry undertake a review of the current MCSCS Correctional Services’ Use of Force Model and the effectiveness of the use of force training against evidence-based best correctional practices. This review must take into consideration the daily perception of risk and danger that correctional employees face, rather than the periodic occupational stressors that are experienced by police officers.

-

The ministry may wish to consider the new Engagement and Intervention Model utilized by the Correctional Service of Canada and best practices used to manage violence in other confined settings, such as forensic mental health or dementia units of long-term care facilities.

-

I recommend that the ministry revise the language of the current Use of Force policy to align with international standards of inmate treatment that allow for use of force only in accordance with safety and security objectives. I further recommend inclusion of a definition for the term ‘discipline’ to prevent ambiguity and conflation with the term ‘punishment’ in the MCSCS Use of Force policy.

-

I recommend that the ministry accelerate its stated plans to review and update the existing Correctional Officer Training and Assessment (COTA) program curriculum. In revising the curriculum, the ministry must incorporate core competencies, and emphasize the importance of fostering an institutional culture characterized by legality, dignity, and respect. Training must always address the dual nature of correctional work which encompasses both security and care.

-

I recommend that COTA redevelopment emphasize verbal and other de-escalation training including specific situational guidance for managing vulnerable or high-needs inmates.

-

I recommend that the ministry work with justice partners and stakeholders to develop training for correctional employees on correctional and human rights law as well as criminal procedure. The newly developed training must be incorporated into the COTA curriculum.

-

I recommend that the ministry establish policy for localized mentorship programs that can be operationalized at each correctional facility. These programs must outline minimum requirements for mentors and be available to all correctional staff and managers.

-

I recommend that the ministry work with policing partners to develop joint policy and provide joint education sessions to correctional employees with the aim of fostering a better understanding of the police role in correctional matters and the legal requirements for criminal proceedings as they relate to pursuing charges when inmates engage in criminal conduct.

-

I recommend that the ministry further collaborate with both provincial and local police services to develop dedicated police units that specialize in the investigation of incidents that occur within Ontario’s correctional institutions.

-

I recommend that best practices for report writing be immediately developed and incorporated into COTA and ongoing staff training, with an emphasis on procedural fairness and minimum evidentiary standards for external legal proceedings.

-

I recommend that the Personal Alarm Location system be implemented at the Toronto South Detention Centre following the completion of the Electronic Security System upgrade in 2019. An evaluation, including a cost-benefit analysis, must be undertaken within one year of the implementation of the Personal Alarm Location system.

-

I recommend that any person entering the secure portion of a correctional facility undergo screening (i.e., handheld/walk-through metal detectors and parcel x-ray machines) in those institutions with the requisite space and technologies.

-

Screening of all persons entering secure areas of Ontario’s correctional institutions is necessary to enhance the personal safety of staff and inmates, as well as maintaining public confidence by detecting and intercepting contraband.

-

I recommend that the ministry engage with the Ministry of the Attorney General to establish guidelines supporting the need for swift and certain sentencing for inmates who are found guilty of a serious assault against correctional staff.

-

I recommend that the ministry explore the introduction of a supervisory correctional officer position (i.e., Correctional Officer 3 [CO3]) to facilitate staff mentorship and assist with compliance and preventative security. Introduction of a supervisory correctional officer position is dependent on the review and potential reclassification of all correctional officer positions by post requirements.

-

I recommend that appropriate role competencies be created for each of the correctional officer classifications (Correctional Officer 1 [CO1] through Correctional Officer 3 [CO3]) and that positions be filled based on a candidate’s ability to meet these competencies.

-

Operational practices

For the majority of men and women in custody in Ontario’s correctional institutions, an act of violence is not listed as their most serious offence (MSO) in the Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS).

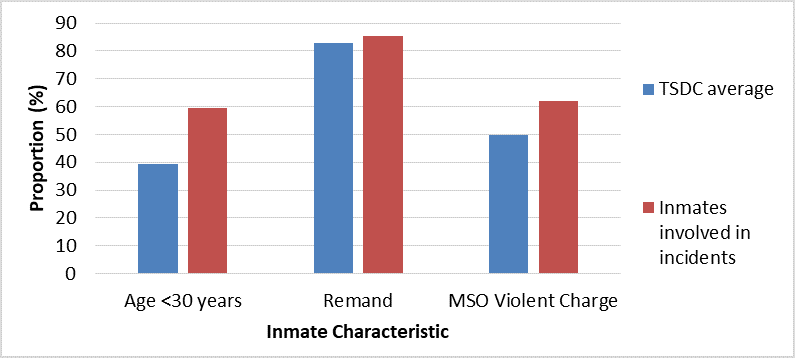

In the Toronto South Detention Centre (TSDC) Case Study, it was found that the inmate population during 2017 was mostly young (40% under age 30 and 71% under age 40), held on remand (83%), and half were in custody for a violent charge as their MSO.

Figure 5. Age, holding type, and most serious offence for inmates at TSDC in 2017

In the Interim Report, the Independent Review Team examined the control mechanisms that are currently available to correctional employees, as well as tools not currently available but that have been proposed by frontline staff. Control mechanisms reviewed in the Interim Report included disciplinary segregation, conducted energy weapons (CEWs), and cell door meal hatches with a ‘sally port’ function. Additionally, operational practices including security classification, inmate housing, and programming were examined.

Control mechanisms

The Interim Report found that the number of misconducts issued in provincial institutions increased between 2010 and 2017. Further, with respect to disciplinary segregation imposed following a misconduct, the Independent Review Team discovered that, while Ontario correctional institutions experienced a decrease in disciplinary segregation placements following the release of a ministry directive in October 2016, segregation continued to be frequently used as a disciplinary tool. The TSDC Case Study provided additional evidence that disciplinary segregation was not only utilized, but was actually employed in the large majority of formal misconducts against staff with guilty findings in 2017. At TSDC, of 102 misconducts with findings of guilt linked to reported inmate-on-staff incidents of violence in 2017, 75 (74%) resulted in a close confinement (i.e., disciplinary segregation) sanction.

Some frontline correctional staff and the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) members of the Provincial Joint Occupational Health and Safety Committee (PJOHSC) have proposed CEWs as an option to respond to institutional violence. The Independent Review Team conducted a jurisdictional scan to examine the use of CEWs in correctional facilities across Canada and discovered that, in each jurisdiction where the use of CEWs were piloted or implemented, they are either rarely used or use has been discontinued entirely due to a lack of evidence linking their use to a reduction in institutional violence.

Correctional officers have also suggested implementation of specialty cell door meal hatches to prevent violent incidents that occur through open hatches. While 19%

Currently, the ministry does not collect data pertaining to whether or not reported inmate-on-staff incidents occurred through the cell door meal hatch. The Independent Review Team was able to conduct this specific analysis on reported incidents at TSDC in its in-depth Case Study, and found that not including threats, 80 reported inmate-on-staff incidents (43%) in 2017 occurred through the cell door meal hatch. As expected, the large majority (79%) of all throwing-related incidents (i.e., of items, liquids, or bodily fluids/substances) occurred through the cell door meal hatch. The majority of incidents that occurred through these hatches occurred in a Segregation Unit, and large proportions of the remaining incidents occurred in a Special Handling Unit or Mental Health Assessment Unit. The TSDC Case Study data suggests that cell door meal hatch-related incidents may be restricted to a subgroup of the inmate population that could be appropriately identified, allowing for precautionary measures to be adopted to avoid such incidents.

While the widespread implementation of cell door meal hatches with a ‘sally port’ function would be ill-advised given the lack of evidence supporting their effectiveness, it may be advisable to consider retrofitting a very limited number of cell door meal hatches in some of Ontario’s institutions for appropriately classified inmates housed on specific units (e.g., Behavioural Care Units). It would be important to ensure that this strategy be implemented alongside other measures (e.g., multi-security units, evidence-based security classification tools, inmate programming, and additional staff training) and implemented after the development of ministry policy governing the proper use of these hatches. Furthermore, rigorous data collection during this pilot study is essential to allow for the assessment of this strategy and its potential benefits and shortcomings. Evaluation of the pilot study must consider demographic information pertaining to the inmates whose cell door(s) is equipped with these specialty meal hatches, other interventions initiated (i.e., programs, additional clinical supports), and outcomes while the specialty hatch is and is not in use (including reported inmate-on-staff violence and inmate-related outcomes such as self-harm or distress).

Inmate intake assessment and classification

The inmate population varies substantially across institutions, based on many factors including geographic location (e.g., urban centres or rural areas) and purpose of the facility (e.g., sentenced or remand centre). As a result, the services required for each institution’s inmate population will vary as well. It is essential that classification, housing and programming needs be tailored to the risk and needs of the inmate population and that consideration be given to overrepresented and vulnerable populations.

Presently, one indicator of behavioural risk is the presence of an active alert(s) in the Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS). Alerts can be added to an inmate’s information in OTIS by most frontline correctional employees. Some alerts have automatic expiry dates following release from custody (e.g., suicide risk alert), but other alerts do not (e.g., gang affiliation). For alerts that do not automatically expire, the onus is on correctional employees to access OTIS and remove an active alert that is no longer relevant. Thus, it is possible that some alerts unnecessarily remain active. This can be particularly problematic, as the current practice for determining custody rating, housing assignment, program access, institutional work assignment, and other elements of sentence management is largely based upon notes in OTIS.

It is essential that OTIS alerts be structured around an evidence-based tool of risk classification; at present, however, it appears that inmates may be assigned a particular OTIS risk alert based solely on the discretion of correctional employees. For OTIS alerts to be effective, they must be accurate and verified; for example, an inmate assigned a Mental Health alert should have this status confirmed by a clinician and not just be dependent on the observation of any correctional employee who may lack clinical training. OTIS is a database accessible across institutions and can play an important role in relevant information sharing in real-time, particularly as individuals may be transferred from one facility to another or be released and supervised in the community. However, lacking verification, the standardization of alerts, and quality control to ensure that only the most relevant alerts remain active in OTIS, the system will continue to lack the reliability necessary for it to be utilized as a classification and management tool.

The Interim Report emphasized the importance of effective risk management through evidence-based classification and risk analyses to determine institutional security and inmate housing needs. The Independent Review Team found that the MCSCS does not conduct regular security risk or classification assessments despite evidence-based research and policies across Canada and much of the world suggesting that regular assessment and proper classification of inmates can reduce institutional violence.

In response to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey, 25%

I truly believe that if we can properly implement and appropriately classify the inmates in our care to the best of our abilities institutional violence can be mitigated. It is understandable that in our line of work an individual may become angry, agitated, or have a crisis. These individuals may have violent and unpredictable outbursts […] If we can identify those inmates who are more prone to have violent outbursts then we can classify them appropriately and provide proper alternative housing and specialized clinical and correctional teams to better implement functional programming to these individuals.

The ministry has acknowledged the need to implement an evidence-based security screening tool and has created an Advisory Group to develop a risk-based security classification instrument to “sort inmates into security levels based on their likelihood of institutional violence, frequent misconduct, and/or escape”.

For example, as the first direct supervision facility in Ontario, it was imperative that TSDC develop an internal classification system and it is one of the few provincial institutions that actively uses an internal screening tool to classify inmates based on housing needs.

Ideally, inmates at TSDC are classified within days of arriving at the facility, although the institution advised the Independent Review Team that “there is not a set timeframe” and the classification process can be lengthy and may be influenced by lockdowns, institutional staffing, safety concerns, inmate court dates, and other relevant classification factors such as gang affiliations, non-associations, and ‘keep separates’.

I honestly believe that the Direct Supervision [DS] model is the way to go however there has to be […] proper internal and external classification of all inmates on an ongoing basis - there also has to be conditions set where an inmate can be deemed ‘Not DS suitable’ and alternatively housed in a non-DS facility as we all know not every inmate is suitable for DS…

Correctional Officer, South West Detention Centre

While some staff expressed concern with the current IPR classification tool and the operational processes being implemented to assess and classify inmates at TSDC, it is worth noting that the Independent Review Team found that fewer incidents of reported inmate-on-staff violence occurred on direct supervision units.

Multi-level housing units

Once classified, it is imperative that inmates are appropriately housed based on their identified security risk and programming or treatment needs. A number of correctional employees indicated that the availability and proper use of alternative housing was integral to the success of institutional operations. For instance, 14%

The ministry has recently made efforts to standardize institutional housing units throughout the province. For instance, the Correctional Services and Reintegration Act, 2018, which received Royal Assent in May 2018, distinguishes between general population housing (“housing for inmates within a correctional institution, other than alternative housing”) and alternative housing (“housing for inmates who require accommodation or services that cannot be provided within the general inmate population, and includes prescribed types of housing”).

Changes to ministry policy governing the placement of special management inmates

Unfortunately, there has been a lack of guidance on how to operationalize these units, and, despite the recent policy revision, Ontario’s provincial facilities continue to operate an array of housing units with different names and various operational procedures. The TSDC Case Study (Appendix A) revealed that the institution has a number of specialty units including intake, segregation, special handling, behavioural management, mental health assessment, special needs, medical, and infirmary. The names and current operating procedures of these units are not yet consistent with the July 2018 ministry policy revisions.

Correctional officers at TSDC indicated in the IROC Institutional Violence Survey that “step- down units” and the use of segregation and other restrictive units were positive means to manage “inmates that are not suitable” for direct supervision, thereby contributing to the success of the inmate supervision model. However, as noted earlier, although this may contribute to fewer reported inmate-on-staff incidents on direct supervision units, reported inmate-on-staff incidents in fact increased on these specialized units at TSDC in 2017. This underscores the need for additional resources and supports, and highlights that restrictive or alternative housing alone will not prevent institutional violence.

Programming

Identifying appropriate institutional placement based on security risk classification and inmate need is the first step in smoother institutional operations. Aligning individual treatment and programming needs to correspond with institutional housing placements is the next logical step in fostering rehabilitation and reintegration efforts. Providing and ensuring access to appropriate programming for inmates has been recognized in the empirical literature as a crucial component of evidence-based correctional practice, and has been linked with benefits such as reducing the potential for institutional misconducts and violence among inmates.

The Interim Report further examined incidents of reported inmate-on-staff violence at Ontario’s three correctional treatment facilities and highlighted the Ontario Correctional Institute (OCI) as having the lowest reported incidents of inmate-on-staff violence between 2012 and 2017 (total of six reported incidents).

OCI is commonly viewed as a unique correctional environment by virtue of its more available clinical resources, engaged correctional staff, emphasis on inmate programming, a pre- screening process prior to admission, assessment during orientation that includes determination of individualized programming needs, employee and inmate relationship, and working environment. In the IROC Institutional Violence Survey correctional employees at OCI acknowledged these features and also offered “extra freedoms”, “good food”, “ample recreation time”, “open setting/no cells/no bars” and “case management” as aspects that facilitate the success of the institution’s inmate supervision model. These are all elements of evidence-based correctional practices,

OCI is a unique facility that is supported by its physical design, relationship custody, programming, clinical resources and engaged Correctional Staff. When there is a deficit in any of these areas the OCI model suffers.

Senior Administrator, Ontario Correctional Institute

Perhaps unsurprisingly, in response to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey, 93%

Figure 6. Inmate recreation areas, OCI

Figure 7. Communal living and dining areas, OCI

Other institutions that have established inmate programs include Central North Correctional Centre (CNCC), which employs eight teachers from Simcoe County District School Board who facilitated the continuing education program offered at the facility. The institution reported that it is the largest adult learning centre in Simcoe County and an audit of the most recent school year, which ran from September 2017 to August 2018, revealed that 90 inmates graduated and that a total of 2,149 credits were earned. Moreover, CNCC employs a dedicated skills and trade manager, a program manager for vocations and industries, and two trade instructors who provide vocational learning and skills supervision. All of these positions facilitate programming designed to enhance employability following release from custody and enable inmates to develop vocational skills while under the ministry’s care. Some of the courses offered at CNCC between September 2017 and August 2018 included “Intro to Business Computers”,

Figure 8. Inmate program areas, CNCC

Similarly, the St. Lawrence Valley Correctional and Treatment Centre (SLVCTC) has adopted several evidence-based correctional practices. SLVCTC is designated as a Schedule 1 hospital and, in essence, functions as a hospital within a correctional facility for provincially-sentenced males with major mental illness.

Figure 9. Resident room, SLVCTC

Unlike OCI, CNCC, and SLVCTC, the Kenora Jail houses both sentenced and remand inmates. The district jail offers an impressive selection of programs, many of which are founded on partnerships with the community. Furthermore, social workers at Kenora Jail frequently attend programming with female inmates in the community. It is common for escorted temporary absences to be granted to the female population in Kenora to enable women housed at the institution to access programs that are only offered in the community.

The importance of inmate programming was reflected in the views expressed by several correctional employees. For instance, one correctional officer stated, “until we maintain discipline and order with better programs that give individuals the ability to succeed in society corrections today is a fail”. Similarly, a sergeant with over 15 years of experience working for the ministry reported:

over my years working with both male/female young offenders, and adult male offenders, they thrive on keeping busy, rules, regulations and consistency. They like to know what their day looks like, they enjoy routine, even if it’s just staff enforcing the same rules day in and day out. Programming needs to happen, outside time needs to happen, telephone calls, showers need to happen.

Programs are essential and should be mandatory. If programs do not happen there should be reports as to why and efforts to ensure the issues are addressed.

Social Worker, Central Region

More broadly, the Independent Review Team found that the majority of correctional employees (58%

Some frontline staff expressed concern regarding the programming currently available to inmates at their institution. One seasoned officer wrote, “it seems to me that the successful model for female inmates was abolished when the original Vanier in Brampton closed. There were work programs available to provide the women with skills and keep them productive. Additionally the women had liberal access to educational programs and liberal access to fresh air”. The officer further advised that, “at [my] current location [inmates] have limited access to these. Due to the crisis in staffing over the past years inmates are subjected to extended lockdowns and have limited access to what few available programs we have. More life skill programming would be an asset”. Similarly, another respondent reported that, “we current[ly] allow inmates out of their cells for 6 hr per day […] What kind of treatment is this? [...] I would like to see the changes to the amount of time inmates are allowed out of their cells. This allows for the initiation of more programs geared toward rehabilitation (school, trade). Zero rehabilitation happens at this jail”. Lastly, a veteran officer submitted, “we lack any sort of meaningful programming. Addiction is a huge problem that we are ignoring”, while a recreational officer advised, “that recreation can have positive impacts of reintegration… [but there were] huge limitations given our available space and condition of the jail” and that “programming is inconsistent, irregular and not available enough to make a difference”.

[…] institutions require more resources and physical space to carry out the appropriate programming to assist with inmate rehabilitation – the union needs to get onboard with rehabilitation.

Sergeant, Northern Region

In addition to limitations on the availability and delivery of inmate programming due to space, financial resources, and staff shortages, which may result in lockdowns that hinder consistency, some correctional employees advised that staff attitudes may adversely impact operations. For example, one respondent emphasized the value of inmate programming and suggested that “perhaps include this [information] in basic [correctional officer] training as they seem to think that programming is just ‘arts and crafts’ and not important”. Similarly, one social worker wrote, “more often than not guards have a power trip over controlling access program staff have with inmates, limiting our ability to perform our jobs and provide essential rehabilitative supports to inmates”.

The negative attitudes that undermine successful inmate programming were apparent in some of the feedback received from frontline correctional staff. One seasoned correctional officer asserted that “the only special programs should be those that deal with mental health issue…all others are a waste of time and focus”. Another officer stated, “the government forgets (or just doesn’t care) that inmates aren’t housed in jails because they are good people. The powers that be are so focused on programming and inmate rights that they have forgotten about their front line correctional officers”.

I am shocked at the lack of respect [correctional officers] have for program staff and the role they have. [Correctional officers] often have no idea what our job entails and have no motivation to support us in completing our jobs. Access to inmates is controlled by [correctional officers] and they take advantage of that and deny access for program staff they do not like.

Social Worker, Eastern Region

The Independent Review Team’s in-depth investigation of TSDC provided considerable insight into many issues related to inmate programming at that institution and that may exist at others as well, though further study is warranted. The programming offered at TSDC generally falls into four categories: institutional work, educational, spiritual, and general interest.

The Independent Review Team was advised that TSDC offers a single institutional work program with a maximum capacity of 40 inmates at any given time and, while the facility does not track the total number of annual participants, staff estimated that 180 inmates participated in 2017.

Presently, TSDC offers only two

TSDC initially advised the Independent Review Team that all inmates had access to the programs offered at the facility. However, upon further investigation, it became apparent that inmate access to programming can be restricted by a number of operational factors, including staff shortages, lockdowns, and the unit on which an inmate is housed. For example, TSDC reported that, in 2017, all of the facility’s course offerings were on direct supervision units; in other words, inmates being housed on more restrictive units were less likely to be able to access institutional programming.

This finding is not unique to TSDC. In fact, other institutions further restrict inmates from participating in specialized programs based on their custodial status. For instance, the admission requirements for the inmate work program at Maplehurst Correctional Complex preclude inmates on remand and those being held pursuant to an immigration deportation order from participating. These operational practices do not align with well-recognized programming principles, including that individuals with the highest risk should be provided with more frequent and intensive programming based on their individual need(s), and that programming can also be successful when accessed in the community.

TSDC also advised that some programs are impacted by the institutional staffing complement. Some are delivered by program officers, that is, correctional officers who have expressed an interest in program delivery and have been temporarily assigned these positions within the institution. While it is commendable that dedicated positions have been allocated for the purpose of delivering programs to inmates, assigning this duty to correctional officers is associated with certain challenges. For instance, these officers are not clinicians and they have not been specially trained in the Risk-Needs-Responsivity model.

Operational practices recommendations

-

-

I recommend that the ministry implement an evidence-based institutional security risk assessment tool that is validated for gender identity, ethnic populations, and Indigenous persons. This tool should be administered to all new admissions upon intake to identify individuals with a propensity for engaging in institutional violence so that staff and managers can be equipped with targeted preventive measures.

-

I recommend that policy and operational practices align with the principle of least restrictive measures by ensuring that all inmates are held in minimum security settings unless the security risk assessment tool confirms additional security measures are required.

-

I recommend that inmates be given written notice and explanation for their initial security risk classification and that reclassification occur at least once every 30 days.

-

I recommend that the ministry establish standardized and validated measures to identify characteristics of inmates that warrant alerts to be entered into the Offender Tracking Information System. Alerts related to an inmate’s behaviour that may be indicative of physical or mental health symptoms must be verified by clinicians.

-

I recommend that the ministry establish dedicated minimum, medium, and maximum security housing areas within each of Ontario’s correctional facilities and provide definitions of the conditions of confinement and operational procedures in these types of custody.

-

I recommend that institutions that do not have the capacity to create separate units create an ‘alternate housing area’ that allows for individualized arrangements in line with the exhaustive list of alternate housing unit types outlined in the ministry’s Placement of Special Management Inmates policy, most recently revised in July 2018.

-

I recommend that the ministry provide standards for the minimum conditions of confinement and an operational routine for each alternate housing unit within six months. These standards must align with the principle of least restrictive measures and be developed with input from the correctional bargaining unit.

-

I recommend that oversight measures be put in place to ensure that updated alternate housing policies, which identify standardized definitions for alternate units, are being implemented appropriately and that this area of correctional practice be a focus of the Inspector General of Correctional Services created in the Correctional Services and Reintegration Act, 2018.

-

I recommend that procedural safeguards and oversight mechanisms be applied to all alternate housing units that restrict out-of-cell time to less than that of the general population.

-

I recommend that the ministry ensure that correctional staff and managers assigned to work in alternate units are carefully recruited, suitably selected, properly trained, and fully competent to carry out their duties in these specialized environments. These posts should be filled first via an expression of interest and not based on seniority alone.

-

I recommend that the ministry establish or contract programs, program delivery, and meaningful activities in which all individuals held in custody may work, study, or participate and that rehabilitative programs comply with the needs identified in individual assessments.

-

I recommend that the ministry collaborate with community partners and stakeholders to identify how existing community-based services and programs could be leveraged to promote an individual’s safe, gradual release from custody.

-

I recommend that the ministry allocate appropriate resources and supports to ensure that evidence-based rehabilitative programs are routinely scheduled and consistently available in each institution based on individualized risk/needs assessments.

-

I recommend that all individuals in custody classified to an alternate housing unit/area be assigned a dedicated case manager and be provided with an individualized care plan, and/or treatment plan, that includes rehabilitative programming where appropriate.

-

I recommend that the Toronto South Detention Centre initiate a one-year pilot study to operationalize a Behavioural Care Unit, as outlined in the ministry’s July 2018 Placement of Special Management Inmates policy, using the following criteria:

-

Enhanced complement of staff to facilitate out-of-cell time and permit for dedicated case managers to ensure that each inmate classified to the unit has an inmate care plan developed, and that the care plan is appropriately followed.

-

Correctional officers to fulfill the role of case managers within the unit and the unit social worker to provide clinical support as needed.

-

Permanent rosters of correctional staff selected first through expressions of interest.

-

Correctional officers to be provided the opportunity to work eight-hour shifts if they are assigned to the Behavioural Care Unit for the duration of the pilot.

-

Dedicated mental health staff (registered nurse, social worker and psychologist) assigned to deliver treatment and programming to inmates classified to the Behavioural Care Unit.

-

Piloting the utilization of the Correctional Officer 3 (CO3) position that is filled via an expression of interest based on competencies required for the position. The CO3 position must be carefully recruited, suitably selected, properly trained and an adequately experienced officer to assist with compliance, preventative security, and increased demands working in this high-stress unit.

-

-

I recommend that the ministry pilot the use of a cell door meal hatch with a ‘sally port’ function for a six-month duration in the three institutions with the highest incidents of hatch-related assaults. These specialty hatches must be limited in number and only be used in Behavioural Care Units following the implementation of clear operational procedures and the development of clear oversight mechanisms.

Further analysis will be required by the ministry to determine the appropriate sites. Additionally, an evaluation of each pilot site must be completed within three months of the conclusion of the six-month pilot study, and must consider demographic information pertaining to the inmates whose cell door(s) is equipped with these specialty meal hatches, other interventions initiated in conjunction with the use of the specialty hatches, and outcomes while the specialty hatch is and is not in use.

-

I recommend that the Toronto South Detention Centre be one of the pilot sites as per recommendation 3.16.

43% of the reported inmate-on-staff incidents (not including threats) that occurred at TSDC in 2017 occurred through the cell door meal hatch. Given that the majority of these incidents occurred in a Segregation Unit, Special Handling Unit or Mental Health Assessment Unit, it is recommended that TSDC pilot the use of these specialty hatches in their Behavioural Care Unit. This pilot should be six-months in duration with an evaluative review taking place immediately following the pilot, as per recommendation 3.16.

-

Footnotes

- footnote[14] Back to paragraph IROC, Interim Report, supra note 9.

- footnote[15] Back to paragraph Following the report of workplace violence, a written review is then conducted by the manager/supervisor including recommendations for steps to take to prevent future workplace violence.

- footnote[16] Back to paragraph At times the IIR may be completed by a staff sergeant if the sergeant/manager is otherwise occupied and unable to complete the IIR.

- footnote[17] Back to paragraph IROC, Interim Report, supra note 9 at 16.

- footnote[18] Back to paragraph There is a Procedural Checklist of information to include when completing an IIR. This checklist acts as guidance material for sergeants/managers completing the IIR, and when elements are missing, staff at the IMU will attempt to follow-up with regional offices or institutions to obtain the missing information.

- footnote[19] Back to paragraph IROC, Interim Report, supra note 9 at 16.

- footnote[20] Back to paragraph Ibid.

- footnote[21] Back to paragraph Alerts refer to notifications that can be recorded in OTIS by correctional employees. These alerts can include categorization by substance abuse, mental health, management risk, suicide risk, and security threat group.

- footnote[22] Back to paragraph Hans Toch, Peacekeeping: Police, Prisons, and Violence (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1976); See also, Alison Liebling and Deborah Kent, “Two Cultures: Correctional Officers and Key Differences in Institutional Climate” in John Woolredge and Paula Smith (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Prisons and Imprisonment (Oxford UP, 2018), 208-234 (hereafter, Liebling and Kent, Two Cultures).

- footnote[23] Back to paragraph Alison Liebling, Susie Hulley and Ben Crewe, "Conceptualising and Measuring the Quality of Prison Life," The Sage Handbook of Criminological Research Methods (2011); Ben Crewe, Alison Liebling and Susie Hulley, "Staff Culture, Use of Authority and Prisoner Quality of Life in Public and Private Sector Prisons," Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 44, no. 1 (2011) (hereafter, Crewe et al.., Staff Culture); Alison Liebling, “Moral Performance, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment and Prison Pain,” Punishment & Society 13, no. 5 (2011) (hereafter Liebling, Moral Performance); Alison Liebling, “Why Prison Staff Culture Matters,” in James Byrne, Faye Taxman, and Donald Hummer (eds.), The Culture of Prison Violence (Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2008), 105-122; Alison Liebling, “Distinctions and Distinctiveness in the Work of Prison Officers: Legitimacy and Authority Revisited,” European Journal of Criminology 8, no. 6 (2011) (hereafter, Liebling, Distinctions).

- footnote[24] Back to paragraph Jill A. Gordon and Amy J. Stichman, “The Influence of Rehabilitative and Punishment Ideology on Correctional Officers’ Perceptions of Informal Bases of Power,” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 60, no. 4 (2016); See also, Liebling, Moral Performance, supra note 23.

- footnote[25] Back to paragraph Crewe et al., Staff Culture, supra note 23.

- footnote[26] Back to paragraph Donald Specter, “Making Prisons Safe: Strategies for Reducing Violence,” Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 22, no. 1 (2006): 125.

- footnote[27] Back to paragraph Liebling, Moral Performance, supra note 23.

- footnote[28] Back to paragraph Liebling, Distinctions, supra note 23.

- footnote[29] Back to paragraph Crewe et al., Staff Culture, supra note 23.

- footnote[30] Back to paragraph For research examining the impact of the principle of restraint and least restrictive measures (conditions of confinement) and recidivism, see: James Bonta and Paul Gendreau, “Reexamining the Cruel and Unusual Punishment of Prison Life,” Law and Human Behavior 14, no. 4 (1990) (hereafter, Bonta and Gendreau, Cruel and Unusual); Paul Gendreau and Claire Goggin, “The Effects of Prison Sentences and Intermediate Sanctions on Recidivism: General Effects and Individual Differences,” Public Safety Canada (Government of Canada, 2002); Francis T. Cullen, Cheryl Lero Jonson and Daniel S. Nagin, “Prisons Do Not Reduce Recidivism: The High Cost of Ignoring Science,” The Prison Journal 91, no. 3 (2011) (hereafter, Cullen et al., Prisons); William D. Bales and Alex R. Piquero, “Assessing the Impact of Imprisonment on Recidivism,” Journal of Experimental Criminology 71, no. 8 (2012).

- footnote[31] Back to paragraph Ibid.

- footnote[32] Back to paragraph French and Gendreau, Reducing Misconducts, supra note 11; Campbell et al., Prediction of Violence, supra note 11.

- footnote[33] Back to paragraph Liebling and Kent, Two Cultures, supra note 22 at 225.

- footnote[34] Back to paragraph Prior to the 1970s, women in corrections were hired as matrons (working as correctional officers within correctional institutions for women), clerks, and administrative support workers.

- footnote[35] Back to paragraph Maeve McMahon, Women on Guard: Discrimination and Harassment in Corrections (University of Toronto Press, 1999) in Freda Burdett, Lynne Gouliquer, and Carmen Poulin, “Culture of Corrections: The Experiences of Women Correctional Officers,” Feminist Criminology 13, no. 3 (2018): 329-349 (hereafter, Burdett et al., Culture of Corrections).

- footnote[36] Back to paragraph MCSCS data; Burdett et al., Culture of Corrections, ibid at 332.

- footnote[37] Back to paragraph Jill A. Gordon, Blythe Proulx, and Patricia H. Grant, “Trepidation Among the “Keepers”: Gendered Perceptions of Fear and Risk of Victimization Among Corrections Officers,” American Journal of Criminal Justice 38, no. 2 (2013): 245-265.

- footnote[38] Back to paragraph Jill A. Gordon and Thomas Baker, “Examining Correctional Officers’ Fear of Victimization by Inmates: The Influence of Fear Facilitators and Fear Inhibitors," Criminal Justice Policy Review 28, no. 5 (2017): at 463 (hereafter, Gordon and Baker, Officers’ Fear); See also, Burdett et al., Culture of Corrections, supra note 35.

- footnote[39] Back to paragraph Gordon and Baker, Officers’ Fear, ibid.

- footnote[40] Back to paragraph Gaylene S. Armstrong and Marie L. Griffin, “Does the Job Matter? Comparing Correlates of Stress Among Treatment and Correctional Staff in Prisons,” Journal of Criminal Justice 32, no. 6 (2004). See also, IROC, Interim Report, supra note 9; Rose Ricciardelli, Nicole Power and Daniella Simas Medeiros, “Correctional Officers in Canada: Interpreting Workplace Violence,” Criminal Justice Review (2018) (hereafter, Ricciardelli et al., Correctional Officers in Canada).

- footnote[41] Back to paragraph Abdel Halim Boudoukha et al., “Inmates-to-Staff Assaults, PTSD and Burnout: Profiles of Risk and Vulnerability,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 28, no. 11 (2013); See also, R. Nicholas Carleton et al., Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada, supra note 2 (this study has shown that alongside police officers and paramedics, correctional officers are most likely to experience mental disorder from work-related stress, including symptoms associated with PTSD).

- footnote[42] Back to paragraph Based on 412 (of 781) correctional officer respondents who either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “I feel safe working at my current institution”.

- footnote[43] Back to paragraph Based on 255 (of 388) respondents who did not indicate that they were correctional officers and either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I feel safe working at my current institution”.

- footnote[44] Back to paragraph Christina Howorun, “Inmates, Staff in Ontario Jails Still Getting Hurt with Contraband Weapons,” CityNews, December 1, 2017. Online: https://toronto.citynews.ca/2017/12/01/contraband-weapons-ontario-jails/; CBC News, “7 Inmates at London, Ont. Jail Overdose Within Minutes of Each Other, Police Say,” CBC News London, August 9, 2018. Online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/london-ontario-emdc-inmates-overdose-1.4779802.

- footnote[45] Back to paragraph As of November, 2018, Fort Frances Jail does not have an operational body scanner.