SIU Director’s Report - Case # 14-OCD-178

Issued: May 8, 2015

Explanatory note

The Ontario Government is releasing past SIU Director Reports (submitted to the Attorney General prior to May 2017) that include fatalities involving a firearm, physical altercation, and/or use of conducted energy weapon, or other extensive police interaction that did not result in a criminal charge.

Justice Michael H. Tulloch made recommendations about the release of past SIU Director Reports in the Report of the Independent Police Oversight Review, released on April 6, 2017.

Justice Tulloch explained that since past reports were not originally drafted for public release they may have to be edited substantially to protect sensitive information. He took into account that confidentiality assurances were given to various witnesses during the course of SIU investigations, and recommended that some information be redacted in the interests of privacy, safety, and security.

As recommended by Justice Tulloch, this explanatory note is being provided to assist the reader’s understanding of why certain information is redacted in these reports. Notes have also been inserted throughout the reports to help describe the nature of the information that was redacted and why it was redacted.

Law enforcement and personal privacy information considerations

Consistent with Justice Tulloch’s recommendations and guided by section 14 of the Freedom of Information and Protection to Privacy Act (FIPPA) (relating to law enforcement information), portions of these reports have been removed to protect:

- confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by the SIU

- information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding

- witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation, provided to the SIU in confidence

Consistent with Justice Tulloch’s recommendations and guided by section 21 of FIPPA (relating to personal privacy information), personal information, including sensitive personal information, has also been redacted, except that which is necessary to explain the rationale for the Director’s decision. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- subject officer name(s)

- witness officer name(s)

- civilian witness name(s)

- location information

- other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation, including in relation to children

- witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation, provided to the SIU in confidence

Personal health information

Information related to the personal health of individuals that is unrelated to the Director’s decision (taking into consideration the Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004) has been redacted.

Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from these reports because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner’s inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.

Director’s report

Notification of the SIU

Notification date and time: 08/03/2014 at 0403 hours

Notified by: Police

On Sunday, August 3, 2014, at 0403 hrs, Notifying Officer of the Thunder Bay Police Service (TBPS) notified the SIU of Deceased’s custody death. Notifying Officer reported that on Saturday, August 2, 2014, at about 1614 hrs, Deceased was arrested for breach of recognizance for being intoxicated in a public place. At 1638 hrs, Deceased was transported to the police station and taken to a cell. On August 3, 2014, sometime before 0300 hrs, Subject Officer noticed Deceased was in medical distress and called the EMS. The EMS tried to revive Deceased in the cellblock, but he died. Deceased’s body was transported to the Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Centre (TBRHSC).

Overview

On August 2, 2014, Witness Officer #3 and Witness Officer #4 responded to a call in regards to an unconscious man in the area of a location. The officers arrived and found a man now known to be Deceased slumping over. Deceased was extremely intoxicated and he was drooling on himself. Deceased required both officers’ help to stand. Deceased was arrested for public intoxication as he was unable to care for himself. Witness Officer #3 conducted a CPIC check and found Deceased to be on a probation order with a condition to abstain from the consumption of alcoholic beverages. The EMS arrived at the scene and assessed Deceased. He was medically cleared by paramedics and transported to the police station.

pronounced Deceased dead.

Scene

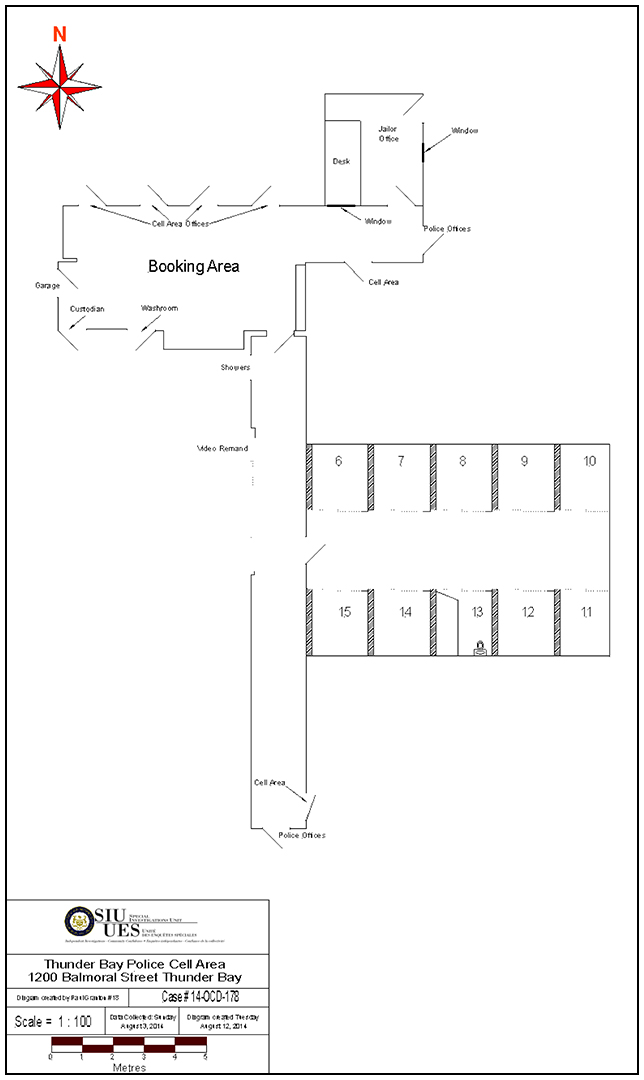

The hallway containing the men’s cells has an overhead camera. Cells 6 to 10 are individual cells with a concrete bunk, toilet and basin. They are on one side of the hall. Each cell is monitored with an individual camera mounted above the door on the opposite wall. Cells 11 to 15 are individual cells with a concrete bunk, toilet and basin. They are on the other side of the hall. Each cell is monitored with an individual camera mounted above the door on the opposite wall. Cell 13 is the middle cell. The door slides to the right. The door and front are barred, with good visibility into the cell. There is Plexiglas at the top of the bars. The floor is constructed of maroon coloured tile. The walls are painted black. The bunk is raised 19 inches off the floor. The cell contains a toilet and basin. The jailer’s office is located at the entranceway. The doorway opens into the hall leading to the booking area. There is a window that views towards the booking area. There are two TV monitors on the wall of the jailer’s office. The monitors show the individual cell areas and a booking room. The watch commander also has two monitors on the wall that shows the individual cells and booking area.

Background information

Deceased had seven Liquor Licence Act violations in the past two years.

The Investigation

Response Type: Attend Immediately

Date and Time Team Dispatched: 08/03/2014 at 0512 hours

Date and Time SIU Arrived on Scene: 08/03/2014 at 1320 hours

Number of SIU Investigator(s) assigned: 3

Number of SIU Forensic Investigator(s) assigned: 1

On Sunday, August 3, 2014, at 0500 hrs, three SIU investigators and two forensic investigators (FIs) were assigned this investigation. Due to delays in flight availability and the fact that the scene (cellblock) was altered due to the EMS attendance, it was agreed the TBPS Scenes of Crime Officer (SOCO) would take photographs and collect the evidence.

The SIU FIs attended at the TBRHSC and sealed the body bag of Deceased. On August

4, 2014, the body of Deceased was transported to the CFS. On August 5, 2014, a PM

examination was conducted.

On August 3, 2014, Subject Officer

On August 3, 2014, the following officers were designated as witness officers and they were interviewed on the date indicated:

- Witness Officer #1 (August 3, 2014)

- Witness Officer #2 (August 3, 2014)

- Witness Officer #3 (August 3, 2014)

- Witness Officer #4 (August 3, 2014)

- Witness Officer #5 (August 3, 2014)

On August 3, 2014, the SIU designated Witness Officer #6

The following civilian witnesses were interviewed on the date indicated

- Civilian Officer #1 (August 3, 2014), and

- Civilian Officer #2 (August 3, 2014)

Upon request the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the TBPS:

- Adult Accused Charge Report

- Background Event Chronology ----redacted and ----redacted

- Case File Synopsis

- Crime Scene Continuity Register

- Incident Summary

- Inspection Report 2008 - Care and Handling of Prisoners

- Witness officers’ notes

- Occur - Person

- Offence Notice - Deceased

- PML - Export

footnote 10 - Policy - NCO /Officer Deployment model and Responsibilities

- Policy - Care and Handling of Prisoners

- Prisoner Management Log (PML) - Deceased - redacted

footnote 11 - Prisoner Management Log - Deceased - unredacted

- Supplementary Occurrence Report completed by Witness Officer #6, and

- Supplementary Occurrence Report completed by Witness Officer #7

The SIU Affected Persons Coordinator (APC) became involved at the outset and dealt with and assisted Deceased’s family with several matters, making referrals to various resources the family could utilize.

Confidential witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence (Law Enforcement and Privacy Considerations)

Director’s Decision Under s. 113(7) of the Police Services Act

Deceased died while in the custody of the TBPS shortly after midnight on August 3,

2014. He was in cell # 13 of the police station, having been lodged there following his arrest for public intoxication the prior afternoon. The evidence establishes a sorry lack of diligence on the part of those officers who had dealings with Deceased during his period of custody. The officers were duty bound to care for Deceased. I am satisfied that the officers failed in their duty and that their failure to take better care of Deceased endangered his life. I am also satisfied, however, that their lack of care was not so egregious as to attract criminal liability.

Deceased had been arrested by Witness Officer #4 and Witness Officer #3. They were responding to a call regarding an unconscious male located outside a church. They found the male – Deceased – and quickly realized that he was seriously intoxicated. He was having difficulty standing and walking, and was variously responsive to the officers’ questions. The officers managed to walk him over to their cruiser. Paramedics soon arrived. Deceased complained of difficulty breathing. However, his concerns were dismissed by the paramedics and the officers. It seems they were of the view that Deceased was feigning illness to avoid going to jail. In their incident reports, prepared days after the event, the two paramedics who dealt with Deceased indicate that he seemed fine and was having no difficulty breathing. The paramedics left the scene and the officers placed Deceased in their cruiser and headed for the station.

The officers arrived at the station shortly before 1700 hrs and lodged Deceased in cell

# 13. He would remain there until his death about seven hours later. In fact, it was a further three hours before his lifeless body was discovered in the cell.

There is plenty of blame to go around as far as the officers are concerned. The investigation has revealed a largely cavalier attitude in the manner in which Deceased was cared for while in their custody. Beginning with the conduct of the arresting officers, there is no indication in their notes and statements, nor in the reports filled out by the paramedics, that they bothered to inform the paramedics that they had observed Deceased with breathing difficulties. One is left to imagine that the paramedics might have taken the state of Deceased’s health more seriously were his complaints more than simply words. Once at the station, almost inexplicably, these same officers failed to mention Deceased’s complaint of breathing difficulties to any of the officers who would have primary care of Deceased while in cells. This, despite the fact that both officers observed Deceased with shortness of breath while he was being escorted to his cell. When Deceased asked to be taken to the hospital again because of his shortness of breath, Witness Officer #3 refused. As the officer explained in his/her SIU interview, the paramedics had cleared Deceased. The booking video further recorded Witness Officer #3 “guessing” that Deceased’s breathing problems were related to his drinking.

Witness Officer #5 was the jailer when Deceased was first brought to the station. He made a point of indicating in his SIU interview that it was not his responsibility to make note of information relating to a prisoner’s injuries, drug or alcohol consumption, or suicidal tendencies. Strictly speaking, he may be right, but the officer’s failure to make reasonable inquiry of the arresting officers regarding Deceased’s condition was striking. Had Witness Officer #5 simply asked, one can only presume that he would have learned that Deceased had been seen and heard to be having trouble breathing.

Witness Officer #2 was the watch commander at the station when Deceased arrived. She downplayed her role and responsibility in relation to the welfare of prisoners at the station, at one point indicating that she had no responsibility for checking the welfare of prisoners on their arrival at the station. Witness Officer #2 failed to grasp that the well-being of prisoners is a collective responsibility, one in which the watch commander plays a lead role. The video monitors in the office she occupied were intended for that very purpose. Witness Officer #2 does say that she kept an eye on Deceased via the monitors. Given her attitude regarding the extent of her duties, however, one is left to wonder how vigilant her watch was.

Witness Officer #5 and Witness Officer #2 were relieved by Subject Officer (the designated “subject officer”) and Witness Officer #1 at about 1800 hrs and 1900, respectively. Witness Officer #5 says he provided Subject Officer no information regarding Deceased’s intoxication. Unlike Witness Officer #2, Witness Officer #1 says he/she was responsible for making physical checks of the prisoners in custody. Witness Officer #1 explains that he was unable to fulfill that duty owing to some physical ailment, Sensitive Personal Information. As a result, Witness Officer #1’s duties had been curtailed to prevent him/her from attending the cellblock. According to Witness Officer #1, Subject Officer alerted him/her to a problem in Deceased’s cell just prior to 0300 hrs. It was about that time that Subject Officer, realizing that Deceased was in medical distress, entered his cell and confirmed he was lifeless.

TBPS policy requires that the jailer make physical checks of the prisoners every half hour, and no less than once every hour in the case of a pressing circumstance requiring the jailer’s attention elsewhere. Subject Officer failed in that duty. In fact, the cellblock video last records Subject Officer entering the cellblock to give Deceased a juice box and granola bar at 2142 hours. In fact, no one appears to enter the cellblock after that time, meaning that Deceased was left unattended and personally unchecked for upwards of five hours. On the face of the evidence, there is no suggestion that this was a particularly busy night at the station or that Subject Officer was occupied with more important matters during this time. This case is close to the line. The offence that arises for consideration, in my view, is failure to provide the necessaries of life under section 215 of the Criminal Code. Subsection

215(1)(c) provides as follow:

Every one is under a legal duty to provide necessaries of life to a person under his charge if that person is unable by reason of detention … to withdraw himself from that charge, and is unable to provide himself with necessaries of life.

Subsection 215(2)(b) states:

Every one commits an offence who, being under a legal duty within the meaning of subsection (1), fails without lawful excuse, the proof of which lies upon him, to perform that duty, if … the failure to perform the duty endangers the life of the person to whom the duty is owed or causes or is likely to cause the health of that person to be injured permanently.

There is little doubt that Deceased’s arrest for public intoxication was lawful. He was highly intoxicated and in no condition to care for himself. The officers were right to arrest him for his own safety. Ironically, I am satisfied that there was a collective failure on the part of the officers involved with Deceased’s arrest and detention to adequately care for him. They were duty bound to do so and yet, time and again, missteps were taken which had the cumulative effect of endangering Deceased’s life.

In my view, the evidence is clear – Deceased ought to have been taken to hospital for medical treatment. The arresting officers had personally observed Deceased having trouble with his breathing. At the scene and at the station, he complained to the officers about his difficulty and asked to be taken to hospital. The officers, it seems to me, ought to have erred on the side of caution and taken him to hospital. Regrettably, they failed to do so and made the situation worse when they neglected to tell others charged with Deceased’s care of his laboured breathing. Had they done so, it might well have been the case that someone would have intervened to secure medical attention for Deceased or, at least, to ensure that he was carefully monitored while in custody.

Deceased’s custodians at the station fared little better. Witness Officer #5 took a hands-off approach in his attitude regarding the extent of his responsibilities over prisoner care. A reasonable officer in his circumstances, I am satisfied, would have made some minimal inquiries of Deceased’s condition. Again, had he done so, a closer watch could have been arranged for Deceased and medical service secured at an earlier point. Witness Officer #2’ appreciation of the extent of her duties also leaves much to be desired. While she was not the primary eyes and ears on the prisoners at the time in question, Witness Officer #2 failed to grasp the true nature of her responsibilities as being the officer with overall and ultimate responsibility for the care of prisoners. With respect to Subject Officer, the investigation is simply at a loss to explain why she failed to conduct personal checks on Deceased as she was required to do pursuant to police policy. Her failure to do some would seem particularly egregious in view of the fact that Witness Officer #1, the watch commander during her shift, was unable to assist with personal inspections given his/her health issues.

In the end, however one cuts it, the evidence strongly suggests that the subject officer, with help from the arresting officers, the jailer she relieved and the watch commanders, failed in her duty of care toward Deceased. Deceased’s cause of death was determined at autopsy to be, “Ketoacidosis complicating diabetes mellitus, chronic alcoholism and septicemia.” It is unclear on the evidence whether the officers’ failure to get Deceased to hospital at some point preceding his death would have saved his life.

That said, I am satisfied on the evidence that the absence of medical treatment, in the words of the offence provision, endangered Deceased’s life.

The real issue in the criminal liability analysis is whether the level of care exercised by the officers was so wanting as to attract criminal liability. As cases like Naglik, 1993 3 SCR

122, Creighton, 1993 3 SCR 3 and F.(J.), 2008 3 SCR 215 make clear, simple negligence will not suffice to ground liability in cases of penal negligence. In the case of failure to provide the necessaries of life, what is required is a finding that the impugned conduct constitutes a marked departure from the standard of care expected of a reasonably prudent person in the circumstances. While close to the line, I am unable to reasonable conclude that the conduct in question meets that test. The critical evidence that mitigates much of the officers’ conduct was that paramedics had dealt with Deceased at the scene and determined that he was fine and did not need to go to the hospital. While it is true that their assessment might have been different had the officers conveyed information regarding what they had seen of Deceased’s breathing, the fact remains that they were in a position to satisfy themselves of Deceased’s health. Parenthetically, I pause to note that there are some real issues regarding the care Deceased received by the paramedics, not the least of which are incident reports authored by the paramedics days after the incident which read more like a defence of their actions than a factual recitation of occurred. Be that as it may, the officers were entitled to place some reliance on what they understood to be a decent bill of health given by the paramedics. This evidence further tempers their failure to convey information about Deceased’s breathing to other officers at the station or to take more seriously Deceased’s laboured breathing at the station and his requests to be taken to the hospital. I wish to stress that this is not to absolve the officers from taking what in my view would have been reasonable steps in Deceased’s care; it is only to suggest that their failure to do so was not without some context or explanation.

The same goes for the other officers, including Subject Officer. To be sure, they knew enough about Deceased’s intoxicated state to put them on notice that he required careful watch. That said, the simple fact remains that they did not appreciate, nor were they told of, Deceased’s complaints of breathing difficulties. And what they did know and see, at least for a significant portion of Deceased’s time in custody, did not suggest he was in medical distress or in need of immediate medical attention. For example, the booking and cellblock video recordings show that Deceased answered questions at the time of his booking, appeared to be breathing normally for portions of time and was active various times until his last movement just after midnight. Indeed, his conduct during this time, including sitting and sleeping on the ground, was typical of intoxicated prisoners, says Witness Officer #1. Also important are the automated records produced by the TBPS prisoner management system, which records Subject Officer checking Deceased 26 times between 1858 hrs and 0249 hours, including 12 times between 2142 hrs and 0249 hours. While this latter series of purported checks was clearly not the result of personal inspections (given the cellblock video), I cannot dismiss the possibility these checks were made via the monitors Subject Officer had available to her in the jailer’s office.

In the final analysis, I am satisfied that Subject Officer was derelict in her duty to care for Deceased. She was not alone in failing Deceased. A tragic series of missteps by all of the officers involved in Deceased’s custody conspired against him that day. In some ways, it is because the blame in this case is spread wide across the officers that there is insufficient evidence that any one officer is sufficiently blameworthy to attract criminal sanction. Be that as it may, while I am satisfied on the evidence that the care Deceased received from the police was substandard, I am not satisfied on balance that the core of any one officer was markedly so in the circumstances. For the foregoing reasons, the grounds in this case fall short of proceeding with criminal charges.

Date: May 8, 2015

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Appendix "A"

All officers answered all note related questions and there were no issues with any responses.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph See “Documents”, ‘Call Incident Report.’

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Deceased’s body was displaying signs of rigor/livor mortis (Latin: rigor "stiffness", mortis"of death" - is the recognizable sign of death, caused by chemical changes in the muscles after death, causing the limbs of the corpse to become stiff and difficult to move. It commences after about three to four hours, reaches maximum stiffness after 12 hours). Livor mortis (Latin: livor-"bluish color," mortis-"of death" - is a settling of the blood in the lower portion of the body, causing a purplish red discoloration of the skin).

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph See “Documents”, ‘Case File Synopsis.’

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph See “Documents”, ‘History & Physical

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph All the above mentioned materials were requested and received.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph Mr. Greg Stephenson, President of the TBPA informed the SIU Subject Officer had been in contact with her counsel, Counsel. Subject Officer will not be providing a statement.

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph See “Documents”, ‘Supplementary Occurrence Report.’

- footnote[8] Back to paragraph See “Documents”, ‘Supplementary Occurrence Report.’

- footnote[9] Back to paragraph Civilian Witness #3, Civilian Witness #4 and Civilian Witness #5 were in the same cellblock with Deceased. By the time the SIU investigators arrived at the TBPS HQ, they were already released from custody and attempts to locate and interview them were to no avail, due to the fact that they had no fixed addresses. Their check time is identical to Deceased’s entries made by Subject Officer. See “PML-Export.”

- footnote[10] Back to paragraph Prisoner Management Log incorporating all prisoners.

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph See “Thoroughness/Integrity Issues.”