Treatment outcomes for Co-Morbid Tourette Syndrome and associated disorders in a specialized outpatient tertiary clinic

Abstract

Tourette Syndrome (TS) is a neurodevelopmental condition consisting of multiple motor and one or more phonic tics. Reviews have documented the very high co-morbidity of TS and other neurodevelopmental and anxiety disorders, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Previous research and existing evidence-based treatment guidelines indicate treatment for OCD and IED remain effective when considerable comorbidity exists. Current research results were consistent with this pattern, with support shown for the specialized clinic in treating children with TS and associated disorders. Continued symptom reduction from post treatment to follow-up suggests support for building skills with this client population.

Purpose

Background

Longitudinal studies have documented the significant emotional, social, and learning impact these disorders have on a child’s overall adjustment and development (Storch et al., 2007). A significant impact from these disorders has also been found for caregivers of these children, and their family members. Impaired functioning and high-co-morbidity rates have also been found to continue into late adolescence (Gorman, 2010). Although best practices for psychological interventions for TS have begun to emerge, there is a continued need for outcome evidence on interventions for this complex group of youth (Woods, Conelea, Walther, 2007).

Purpose

The current study examined treatment outcome evidence for children/youth participating in one or more treatment groups addressing symptoms of co-morbid OCD or Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED). Preliminary analyses were also conducted to understand any potential differences between children and their families who accessed one versus multiple treatment groups within the specialized clinic. Post-treatment outcomes for clients were also analyzed irrespective of treatment group.

A priori hypotheses included an expectation that participants in either treatment group would display significantly reduced symptoms, a decline in overall impairment from pre to post-treatment, and treatment gains that would be maintained at the 6-week follow-up.

Group Treatment - OCD

Treatment for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder consisted of a treatment group based on Exposure & Response Prevention (ERP). The ERP group met once a week for twelve 60-90 minute sessions. The treatment approach borrowed heavily from, and elaborated upon, the protocols found in the book, “Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Cognitive-Behavioural Treatment Manual” by John S. March, M.D. and Karen Mulle, M.S.W (1998). Elements used from their program, entitled, “How I Ran OCD Off My Land”, consisted of developing a tool-kit for bossing back OCD, mapping OCD, using ERP, family sessions, relapse prevention, and booster calls and sessions (“tune ups”).

Group Treatment - IED

IED symptoms were addressed in the Self Management Group (SMG), which met for 12, 60 minute sessions with parents/guardians. The premise was that participants had difficulty regulating their emotional arousal due to deficits in inhibitory ability. The experience of profound loss of control, and immense frustration it can create, leads to reactive anger. As this is due to a neurological skill deficit, it cannot be punished away nor can the child simply choose not to act in this manner. Instead, it is vital to learn new coping skills for these deficits to prevent the overload, therefore reducing the frequency of reactive anger. Given that rage represents a skill deficit and loss of control, few differences were expected in the overall intensity of rage episodes given that this process is not modifiable. Sessions included intensive training in using an expanded model of the Collaborative Problem-Solving approach (Dr. Ross Greene).

Measures

Participants

Data was collected at pre-treatment, post-treatment, 6 weeks, and 6 month (on the CAFAS) follow-up for clients. Mean age of clients was 12.57 years (SD = 1.9) for ERP and 11.15 years (SD= 1.7) for SMG clients. Ages ranged from 9 to 15 years. All clients had previous diagnoses of TS and associated disorders, such as ADHD, OCD, and IED.

CAFAS (Hodges, 2000). The CAFAS is a multidimensional rating of level of functioning, consisting of subscales assessing functional impairment in 8 domains. Each is rated from 0 (no impairment) to 30 (severe impairment).

Exposure & Response Prevention (ERP) for OCD

National Institute of Mental Health - OCD Scale (NIMH; March & Mulle, 1998). The NIMH is comprised of a Global Obsessive-Compulsive Score and Clinical Impairment Score The Global Score is evaluated on a scale (1-15) that best describes the present clinical state of the client’s symptoms based on guidelines. The Impairment Score evaluates the degree of impairment by present symptoms on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “normal” (1) to “among the most extremely ill” (7).

Self-Management Group (SMG) for IED

Rage and Episodic Dyscontrol Scale - Modified (REDS; Budman, et al., 2003). The REDS provided information on the frequency and intensity of the child’s rage behaviour using a 4-point scale ranging from “no rages in a month” (0) to “1 or more per day” (3) and “yells and screams, but still can control anger” (0) to “becomes violent or dangerous; must be restrained” (3).

Results

CAFAS

All clients demonstrated significant reductions from the beginning to the end of treatment in their overall functioning, functioning at home, and in their mood regulation. Gains in the latter two areas were maintained at the 6 month follow-up (CAFAS Mood/Emotions t(10) = 2.33, p < .05, CAFAS Total, t(14) = 2.80, p < .05).

Exposure and Response Prevention for OCD

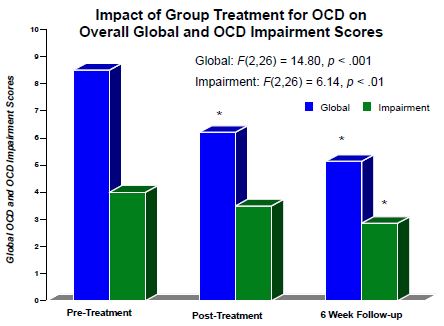

A repeated measures MANOVA was conducted for 14 ERP clients. Analyses demonstrated significant results over time for the Global OCD and Clinical Impairment scores. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that for Global symptoms, a significant decline was noted across time, including from pre-treatment to post-treatment, and a subsequent decline to the 6 week follow-up. Impairment scores did not significantly decline from pre to post-treatment, but a significant decline was noted from the post to the 6-week follow-up time point.

Self Management Group for IED

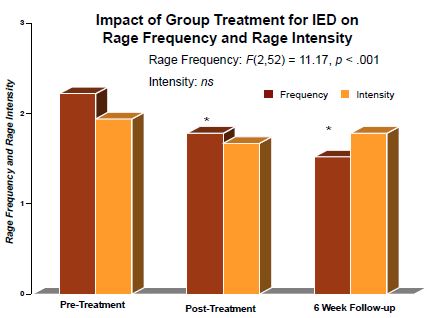

A repeated measures MANOVA was conducted for 27 SMG clients on the Intensity and Frequency of the child’s rage behaviour on the REDS. Results indicated no significant decline in the overall intensity of the observed rage behaviour. However, results demonstrated a significant reduction in the overall frequency of the rage behaviour. Post-hoc analyses indicated a significant decline in the frequency of the rage behaviour across time from pre to post- treatment, and post-treatment to a 6-week follow-up.

Treatment Results - OCD

Treatment Results - IED

Self-Management Group

What Fills My Beaker?

- Getting thoughts or scary pictures stuck in my head!

- Not finishing something!

- Getting distracted!

- Having to wait for things!

- Getting blamed for things!

- Forgetting stuff!

How do I Know my beaker is flling?

- Grind teeth…

- Tightened fists…

- More tics…

- Can’t stop thinking about what is bugging me

- Feel like hitting something..

Conclusions

This study added to the research on psychological interventions for Tourette Syndrome and associated disorders. Overall, findings demonstrated support for the clinic in treating children with Tourette Syndrome and associated disorders. Repeated measures MANOVA analyses demonstrated significant reductions in symptoms and impairment levels at post-treatment for clients participating in the ERP treatment group for OCD symptoms and the Self Management treatment group for rage behaviours. Notable were the findings that these treatment gains were maintained (or even significantly improved) at follow-up.

Both treatment groups are important in that treatment is conceptualized as skill-based and as providing clients with coping skills for areas in which they have skill deficits. This knowledge, coupled with many opportunities for practice and review, empower children and their families to make continued positive changes. The pattern of results demonstrating continued symptom reduction from post-treatment to a 6-week follow-up for clients in the ERP and SMG was consistent with this idea, suggesting support for the focus on building skills with this client population that can continue to be practiced and sustained over time (March & Mulle, 1998; Greene & Ablon, 2005).

Select References

Budman, C.L., Rockmore, L., Stokes, J. & Sossin, M. (2003). Clinical phenomenology of episodic rage in children with Tourette Syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 59-65.

Gorman, D.A. et al. (2010). Psychosocial outcome and psychiatric comorbidity in older adolescents with Tourette syndrome: Controlled study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197, 36-44.

Greene, R.W., & Ablon, J.S. (2005). Treating explosive kids: The collaborative problem solving approach. New York: Guilford.

Woods, D.W., Conelea, C.A., & Walther, M.R. Barriers to Dissemination: Exploring the criticisms of behavior therapy for tics. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 14(3), 279-282.