Section 2: opportunities and challenges for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

The review’s consultations with external stakeholders as well as officials from the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development and the WSIB highlighted several areas that represent opportunities and challenges for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board in the coming years. These issues are multi-faceted. Some are internal to the WSIB such as the role of technology to improve the claims and adjudication processes. Others are external such as evolving medical research and social norms on matters of occupational disease and mental health.

How the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board responds to these future opportunities and challenges will be critical to protecting and maintaining its financial sustainability and better serving workers and employers in the province. But, just as importantly, it is also critical to retaining public trust and confidence in the WSIB as a public institution.

This review has therefore focused on these forward-looking issues in order to better understand how they affect workers, employers and the WSIB, and what reforms may be required to the WSIB’s operations and the government’s legal and policy framework so that the upsides are realized and the downsides are mitigated. The outcome of this process of transition should be a stronger, more effective Workplace Safety and Insurance Board that is able to provide responsive, timely and individualized services on behalf of workers and employers. This is ultimately key to ensuring that the organization remains a vital and dynamic part of Ontario’s modern social safety net.

This section of the report outlines these forward-looking opportunities and challenges and sets out the case for related operational, legal and policy reforms.

2.1. Setting a sufficiency ratio for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

Protecting the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s vastly-improved financial position is foundational to the organization’s ongoing effectiveness. It is the starting point for any forward-looking analysis or planning.

Neither the government nor the WSIB can permit the organization to fall backwards into the structural underfunding that produced its massive unfunded liability. But it also cannot fall into a path of structural overfunding which can produce its own set of challenges. That means setting parameters around the WSIB’s financial framework that protects it against the actions and influences that contributed to its past problems and precludes the emergence of new ones.

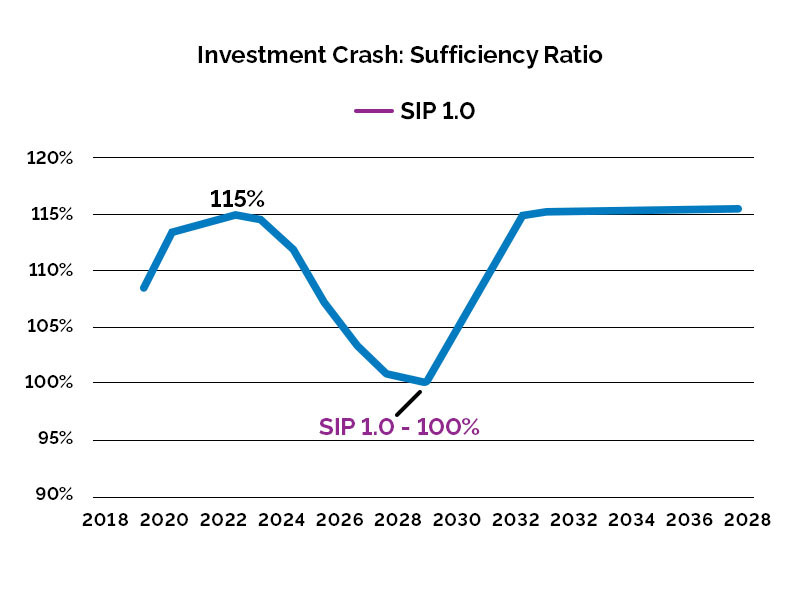

The first step is establishing a sufficiency ratio that guides the annual rate-setting process on an ongoing basis. Remember the sufficiency ratio and timeframes set out in Regulation 141/12 have since been superseded. The regulation directed the WSIB to achieve a 100% target by 2027. It is presently 110.2% funded

This has created uncertainty for the WSIB and its stakeholders. The review’s consultations heard from various stakeholders (including the WSIB itself) that new regulatory guidance from the government could provide greater clarity around the WSIB’s overall financial strategy and protect against the risks of underfunding and overfunding. It could also issue guidance on how to manage the distribution of excess or surplus funding.

What might an updated version of Regulation 141/12 set out for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board? There are various perspectives on the relative risks of underfunding and overfunding and the right sufficiency ratio for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board. The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board has carried out considerable analysis and research on asset-liability studies and adverse scenario projections to determine what a sensible and balanced sufficiency ratio might be in the short and medium-term. The reviewers met extensively with WSIB officials to understand this analysis, test its assumptions and ensure that it represents a reasonable basis to establish a reserve threshold.

As part of its 2020 rate setting, the WSIB has notionally sought to target a sufficiency corridor

between 115% and 125%. This target reflects the board of directors’ goal of enhanced assurance

that the WSIB will not fall below a sufficiency ratio of 100%.

Targeting such a corridor is sensible, especially in the short-term. It can not only protect against economic downside and premium rate volatility, it can also provide a financial buffer as the WSIB fully unwinds the past claims costs from its premium rate. Remember the upcoming year will be the first time in several years that the past claims costs component will not provide implicit slack in premium rates. This is not to preclude adjustments to the sufficiency ratio over time. But it seems prudent that the target in the short-term errs on the side of stability as the WSIB shifts to a premium rate comprised of new claims costs and administration as well as implements the new rate framework.

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s analysis shows that such a target provides a high probability that the system remains at or above 100% funding for the foreseeable future. This judgement reflects a series of asset liability studies and economic modelling that is broadly comparable to how provinces such as Alberta and Manitoba determine their financial planning. It is notable for instance that under such a policy the WSIB could withstand an economic shock similar to the 2008-09 recession and not fall below a 100% threshold (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Workplace Safety and Insurance Board insurance and loss of retirement income funds asset-liability study (based on 2008-09 recession)

Source of Data: Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s plan is therefore sensible with two key caveats. It is important to highlight both.

The first is that a sufficiency ratio corridor of 115% to 125% should be limited to a defined period of time that enables the WSIB to unwind the past claims costs component of premium rates and ensure that its pricing model for new claims costs and administration is correct. Assuming its pricing is accurate, the WSIB and the government may decide that such a significant cushion is unjustified and in turn lower it to 105% or 110%. The transition to the new rates under the rate framework will be mostly complete within five years. It seems reasonable therefore that the sufficiency ratio should be revisited at that time.

The second is that the regulation prescribing a sufficiency ratio should also establish general parameters for the distribution of excess funding above a sustainability reserve. The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board should not be permitted to accumulate large surpluses. But as important as it is to avoid overfunding, it is also critical that surplus distribution is principle-based and transparent. It should not be ad hoc or subject to politics.

A surplus distribution policy could assume different forms such as a dividend or premium credit for employers. The former is delivered in a one-time dividend payment to employers based on a combination of industry, rate group and health and safety performance. The latter is delivered in a one-time reduction in an employer’s premium rate in a subsequent year.

The form of surplus distribution is less important than the process and parameters. The Alberta Workers’ Compensation Board was one of the first workers’ compensation boards to codify clear parameters for surplus distribution in its funding policy. It stipulates that, at the end of the fiscal year, the board of directors may

consider surplus distribution in the form of a credit applied to an employer’s account, or funding for health and safety initiatives if the sufficiency ratio exceeds its 114 – 128% target range

The Ontario government should follow Alberta’s lead and prescribe the parameters for surplus distribution in regulation. The regulation should instruct the WSIB to consider surplus distribution if the sufficiency ratio exceeds 115% and (at the board of directors’ discretion) require that it distribute surpluses if the sufficiency ratio surpasses 125%. The WSIB can consult with stakeholders on the best design for surplus distribution and codify the results of these consultations — including the specific procedures and mechanism for surplus distribution — in its funding policy.

It should be observed that enacting a new regulation to replace Regulation 141/12 may first require legislative change. Regulation 141/12 was enabled by a legislative amendment in 2013 that permitted the government to set regulatory conditions for the WSIB when the organization’s insurance fund was not sufficient to meet its obligations under the act. The law, as it is currently written, may not permit the government to set conditions in regulation for the WSIB when its insurance fund is sufficient. It is beyond the capacity of the review to reconcile these legal subtleties. The government will need to make a judgment and, if necessary, amend the legislation in order to give itself the power to provide new regulatory guidance.

One of the main benefits of this overall approach is that it will place an implicit onus on the government to ensure its own policy choices do not undermine the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board financial position. Remember the Auditor General observed that a great deal of the WSIB’s past financial challenges were the result of the government choices that imposed new costs on the organization or limited its capacity to raise sufficient revenues to pay for administration and benefits. A regulation requiring the WSIB to meet certain financial thresholds amounts to a high-profile public commitment on the part of the government to the WSIB’s ongoing financial sustainability. It would effectively raise the political threshold for governments in designing policies that touch on the WSIB’s financial position.

2.2. Sustaining and strengthening the rate-setting process

As described in Section 1, the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board has taken considerable steps to improve its processes for pricing claims costs and setting premium rates. The combination of Regulation 141/12, the funding policy and greater rigour in its pricing analysis has contributed to the WSIB’s stronger financial position over the past several years. These are, of course, positive developments. The goal must be to sustain and strengthen the rate-setting process and the WSIB’s financial capacity in order to protect the gains that have been achieved.

Various stakeholders observed that the greatest threat to the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s ongoing sustainability is the potential for government policy in particular and politics in general to disrupt the organization’s financial sustainability.

The primary risk is not from overt political interference in the rate-setting process, as may have been the case in the past

The greater risk is that the government legislates new or enhanced benefits without adequate resources to fully cover them. This is hardly a theoretical risk. The 2009 Auditor General report, for instance, highlighted how previous policy decisions such as the 2007 indexation of worker benefits added to the WSIB’s unfunded liability

The review does not question these policy choices or the government’s authority to make them. But adequate time is required for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board to adjust its rate to account for new or enhanced benefits. The imposition of mid-year costs can preclude planning and, as a result, harm the organization’s financial position.

It is important therefore that the government refrain from mid-year policy changes. This does not mean that the government should never create new benefits or enhance existing ones. That is its prerogative. But it should be stipulated that new or enhanced benefits should come into effect in the fiscal year in which the WSIB can account for these costs in its rate-setting process. This was a past recommendation of Harry Arthurs. It remains a sensible recommendation now. While the government has in recent years collaborated with the WSIB in assessing the system effects when considering legislative or regulatory changes, codifying this expectation in the Workplace Safety Insurance Act, 1997 would help to create greater certainty and stability in the rate-setting process.

Another reform that would improve the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s financial planning is a better use of predictive modeling in its pricing and rate-setting processes. Private sector insurers are increasingly using predictive modeling to anticipate industry and firm-level trends and set rates more precisely. The WSIB has experimented with predictive model analysis but currently does not use any form of predictive modeling in its rate-setting processes. Yet it has a tremendous amount of data that could form the basis of sophisticated predictive modeling techniques. The WSIB should therefore develop a predictive modeling capacity within the organization as part of its efforts to sustain and strengthen its rate-setting processes.

2.3. Implementing the new rate framework

Section 1 described the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s Rate Framework Modernization initiative, its rationale, and how it is being implemented over the coming years.

The new rate framework improves on the current system by simplifying the employer classifications and replacing the existing experience-rating programs. But it will be essential that the WSIB carefully monitors its implementation in order to ensure that it works smoothly in practice. There are specific risks that will require attention and possible adjustments.

One issue is the initial distribution of employers according to the different industry classes will require ongoing adjustments. The initial classification for most firms will be based on a judgment of the firm’s predominant business activity

based on insurable earnings. Yet businesses and business activities are regularly evolving. It will be critical for the WSIB to be flexible as the new model is implemented. The process for determining whether employers are subject to single or multiple premium rates will also need to be consistent and transparent

As part of the transition to the new model, employer stakeholders have advocated for the assignment of a senior manager for each industry class who is responsible and accountable for these types of decisions. Think of it as a key point of contact for employers seeking to understand their grouping, its rationale, and how changes to their business activities will affect it.

This was challenging with 155 rate groups, but it should be doable and sensible with only 34 industry classes. The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board should therefore consider establishing an Industry Class Manager position especially as the new rate framework is phased in. It would be useful from an organizational standpoint to have a senior focal point with whom industry and worker representatives can engage about their unique issues and circumstances.

More generally, the biggest risk of the transition to the new rate framework is the extent to which a greater reliance on experience rating could enhance the incentives for claim suppression. Depending on an employer’s size and its rate group, the percentage of individual experience considered in the rating setting will range from as low as 2.5% to as much as 100%

This is not an indictment of experience rating in general or the model contemplated in the new rate framework in particular. The new model is simpler and more transparent than the panoply of programs that it is replacing. But that does not change the fact that labour unions and injured worker advocates are right to be concerned about how these incentives may affect employer behaviour. The use of a rolling six-year window to set individual premium rates will ostensibly help to mitigate the risks of rising claim suppression. Still, the WSIB will need to be vigilant including, as discussed later, expanding its audits for potential claim suppression.

2.4. Rationalizing Workplace Safety and Insurance Board coverage

Section 1 discussed the evolution of the WSIB’s insurance coverage including the different treatment of Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 employers as well as the workings of the inclusionary model

for coverage and the extent to which it can produce anomalies in the treatment of different firms and business activities.

The question of coverage is one of the most contentious issues facing the WSIB. It has been overshadowed for several years by the unfunded liability, but its elimination has pushed the subject back on the public agenda. There is growing momentum for the WSIB and the government to revisit its model for coverage led by labour unions such as the Ontario Compensation Employees Union.

The case for reform is not without basis. The inclusionary model, which requires the WSIB to render judgments about the inclusion of different firms and business activities, is poorly equipped to handle a fast-moving, innovative economy. The conversion to the North American Industry Classification System will simplify the administrative process of assigning different business activities but it will not change the basic model. The risk, as described earlier, is that certain workers and employers fall through the cracks

, or there are delays in determining their treatment in the inclusionary model.

It can also produce uneven treatment of different workers and employers that are difficult to justify based on evidence or principle. The review’s consultation frequently heard about such anomalies in the system. Some developmental support workers, for instance, are included in mandatory coverage and others are excluded, depending on their employer. Residential care workers who work in retirement homes or senior citizen’s residences are similarly treated unevenly. These anomalies can produce distortions. A part-time residential care worker, as an example, can conceivably work partly in a workplace that is subject to mandatory coverage and partly in one that is not, even though his or her activities and functions are precisely the same.

Fully changing the treatment of currently non-mandatory covered industries may create disruption or unintended consequences. Industries and firms have operated according to the current framework for more than a century and some have made alternative insurance arrangements for their workplaces. There may not be an appetite therefore for moving to mandatory coverage across the economy given the potential effects on business investment and employment. But the WSIB should move to an exclusionary model on a go-forward basis. That is to say henceforth new employers should be subject to mandatory coverage unless the WSIB and the government act to exclude them.

Under such a legal and policy scenario, the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and the government would now be required to take policy or regulatory action to exclude an employer and then justify their rationale. An exclusionary model would ensure that future decisions are more transparent and accountable. The net outcome would ostensibly make for a more principle-based model.

British Columbia’s exclusionary model is a good example of how such a new exclusionary arrangement could work. Section 2 (1) of the British Columbian Workers’ Compensation Act stipulates that this part [compulsory coverage] applies to all employers, as employers, and all workers in British Columbia except employers or workers exempted by order of the board

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and the government should consider adopting a similar legal framework that applies to new and future employers.

There are some current anomalies in Workplace Safety and Insurance Board coverage that justify immediate action. The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and the government should undertake to extend mandatory coverage to developmental supporter workers and those working in residential care facilities as envisioned in Bill 145, which died on the order paper in the 41st Parliament

Related to the question of coverage is the differing insurance schemes for Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 employers. The two separate models are a function of the WSIB’s founding. The review’s research found that it may have even been conceived as an experiment to see how the two models — collective liability and individual liability — worked in tandem. To the extent to which this is true, it seems like 105 years is long enough for an experiment to have run its course.

Maintaining both schemes creates some administrative complexities for the WSIB. Determining the administrative costs attributable to Schedule 2 employers, for instance, has been characterized as complicated and lacking transparency by a 2015 value-for-money audit carried by Ernst & Young

The distinctions between the two schedules and in turn the justifications for maintaining them is, moreover, becoming less obvious. There are two main reasons for this trend.

The first is more Schedule 2 employers are voluntarily opting into Schedule 1 because of the cost certainty of collective liability. This has particularly been the case for municipalities that are struggling to manage the costs of retroactive claims by firefighters and rising mental stress claims by other emergency personnel. Consider the number of Schedule 1 employers has increased by 28% since 2009 and the number of Schedule 2 employers has fallen by 7% over the same timeframe

The second is the WSIB is now using a type of collective provision to pool risk among Schedule 2 employers. This works as a system of financial guarantees to protect claimants from firm bankruptcies. There is no longer a separate operating budget to manage Schedule 2 claims or a separate process for how the claims are treated. In short, the system is increasingly converging to a collective liability model.

Consolidating the two schemes was not an option as long as the unfunded liability persisted. It would have been unfair to require Schedule 2 employers to contribute to past claims costs, given that they were not previously part of the system. But now that the unfunded liability has been eliminated there is an opportunity to consider whether to fully consolidate Schedule 2 employers into the collective liability system.

Incorporating the roughly 590 Schedule 2 employers into the new rate framework would require consultations and possible adjustments to the industry classes and premium rates. It would also require a transition plan for Schedule 2 employers who may have ongoing claims under the individual liability system and would begin to pay premiums into the collective liability system for future claims. The WSIB and Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development would finally need to consider the necessary legislative and regulatory changes as well as the appropriate timeframe for implementation.

Yet, given the changes in pricing model, it seems like an opportune time to bring the experiment of a dual model — collective liability and individual liability — to an end. Moving in this direction would simplify the WSIB’s administration and improve transparency with respect to pricing and administration costs. It would also bring greater cost certainty to Schedule 2 employers. The WSIB and the government should therefore prepare for the consolidation of Schedule 2 employers into Schedule 1 over the medium-term.

2.5. Modernizing and streamlining claims and adjudication

As discussed in Section 1, the WSIB’s current model for claims and adjudication relies on outdated technology and slow, labour-intensive processes. The result is a one-size-fits-all

system that lacks responsiveness and timeliness. Virtually every individual and organization who participated in the review’s consultations emphasized the need for modernization in order to better serve workers and employers.

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board recognizes that it has historically failed to examine its business from an outside-in

perspective and spent too little time thinking about how it serves workers and employers. The result is clear: the WSIB has not kept up with the accelerated pace of change that technological advancements are delivering in the new digital world. It has fallen significantly behind not just its private sector comparators but even among public sector organizations and, as a result, failed to meet the needs and expectations of the people it serves. The need for change is real.

The first step is for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board to structure itself around people’s needs and deliver services that best fit their expectations. People expect the same level of interactions and services they already find in other organizations they deal with on a daily basis. The top priority for the WSIB must be to modernize the claims process by replacing the reliance of paper processing, telephone interactions, and faxing with easy to use online services. Online services that allow people to register claims, check claim status, and communicate digitally, can achieve administrative efficiencies for the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and, more importantly, improve services for Ontarians.

The core services modernization initiative is prioritizing these changes in the immediate term. The expectation is that the digital submission of documents and online system for monitoring one’s status should be available in 2020. This is a positive first step. Further digital enhancements should continue with the goal of a full end-to-end digital solution that allows people to conduct business fully online with the WSIB as soon as possible.

A second, related step is to move to the extent possible to a self-service model for no-lost-time claims in particular and simple claims in general. The average cost of a no-lost-time claim is $344. The average cost of a lost-time claim exceeding three months in duration is $27,753. Yet the current claims and adjudication processes do not effectively differentiate between them. There is no reason that managing low-risk claims (which are primarily about collecting data as opposed to delivering benefits and services) should be as labour intensive as they currently are. A system of online claims for these simple cases as well as fast-tracked adjudication (using a form of e-adjudication) would enable the WSIB to dedicate more resources to complex claims.

As part of a shift to such a risk-based model, the WSIB should set new targets for processing timelines that differentiates between no-lost-time claims and lost-time claims and reports on them separately. The WSIB’s current practice of combining the two types of claims when reporting on its performance on processing timelines is inherently inflationary due to the disproportionate number of no-lost-time claims. Disaggregating the data would provide a clearer sense of the organization’s progress on improving processing timelines.

It should be possible through the use of digital technology, self-service, and e-adjudication to significantly reduce the processing timelines for no-lost-time claims. But, as importantly, it should also help to reduce processing timelines for lost-time claims by refocusing more resources and senior staff on them. Publishing separate metrics for each would enable Ontarians to track the WSIB’s progress.

A third step is to continue to adjust the current model for claims adjudication. The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board has at different times relied on a case manager model whereby specific case managers were responsible for particular industries, employers, or individual claims, and a triage model whereby claims and cases are distributed across the organization based on capacity at any given time.

Both approaches have their weaknesses. The former can lead to an inefficient distribution of staffing and resources if some adjudicators are markedly busier than others. The latter can cause its own inefficiencies by precluding the development of specific competencies and expertise among WSIB staff and causing workers and employers to deal with multiple Workplace Safety and Insurance Board officials on their files. There is a sweet spot between the two, and the WSIB must organize itself and staffing to achieve it. Simple claims, as a general rule, can be resolved through a triage model. More complex ones (including mental stress and occupational disease cases) will require dedicated expertise. The goal must be to ensure that the right claims are being managed by the right people at the right time.

Shifting to a model that focuses resources and expertise on specific types of claims — particularly complex ones — will become more important as the number of mental stress and occupational disease cases grow. The number of mental stress cases, for instance, has already grown by 107% since 2016. Managing this potential major source of new, complex claims will require a combination of process reforms and internal expertise. It is critical that the WSIB is proactive in implementing such changes in preparation of a rising share of cases requiring greater and more specialized attention. The risk otherwise is that the WSIB’s claim and adjudication processes may become overwhelmed and timelines could significantly worsen.

Overall, then, these three areas of improvement are critical to modernizing and streamlining claims and adjudication, addressing a major source of frustration for workers and employers, and positioning the organization for future caseload trends. Failure to make progress in these areas will erode public trust and confidence in the WSIB and could ultimately lead to new demands for more fundamental changes.

It is important, therefore, that not only the WSIB proceeds with its core service modernization initiative, but that it continues to engage stakeholders on its design and implementation. It will need to do so in order to both demonstrate progress as well as seek to input on different aspects such as the functionality of the online portal for both workers and employers.

2.6. Reforming the appeals process

As important as digital adoption and other technological changes are to improving the claims and adjudication processes, there is also need for some accompanying institutional reforms. Section 1 highlighted the appeals process as one area requiring the WSIB’s and government’s attention.

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s current appeals/reconsideration system imposes unreasonable delays by virtue of a myriad of steps and processes that ultimately rarely provide a final decision for the appellant or employer. The appeals/reconsideration system should not be viewed outside the claims continuum.

Streamlining the appeals process can therefore be part of an overall agenda to improve claims and adjudication. It does not need to come at the expense of workers — in fact, the review frequently heard that a streamlined process for appeals could actually improve outcomes for workers. There are three types of reforms that the WSIB and the government should consider.

The first is to consolidate the two layers of reconsideration and appeals presently housed within the WSIB. A single appeals function could draw from a combination of the current approaches of the reconsideration process at the operating level and the Appeals Services Division’s appeals resolution officers. It would provide workers and employers with an opportunity for appeal within the WSIB but not have them stuck in a lengthy, multi-layer process that does not typically produce different results than the initial adjudication. It would, in effect, accelerate appeals to the WSIAT, where the facts of the case can be reconsidered.

The legal and operational framework for a new consolidated appeals function within the Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal would require engagement on the part of the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, the government, and the WSIAT. Considerations would include the design of the appeals function, including the role of in-person hearings; new timeline standards for appeals decisions; human resources and staffing; and possible incremental resources to the WSIAT, which would ostensibly receive more appeals as a result. These are significant considerations that should not be taken lightly. But the rationale for maintaining two separate layers of appeal/reconsideration at the WSIB seems difficult to justify given the evidence of delays and a lack of different results.

The second is to improve how the Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal’s decisions are used to inform the WSIB’s adjudication guidelines and vice versa. It seems unproductive for the WSIAT to overturn the WSIB’s decisions in roughly half of cases and yet it can have no impact on how the WSIB adjudicates different types of cases. There is scope to protect the necessary independence of the two organizations and still enable a greater two-way conversation on cases where key principles are at issue. The goal should be to avoid cases with fundamental similarities, regularly returning to the WSIAT on appeal. A 55 to 65% overturn rate is not in the interest of the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal, workers, or employers.

In what form could this two-way feedback take shape? One option is the creation of a Quality Table with key representatives from both organizations. The purpose of the group would be to identify and anticipate trends through data analytics and actual case outputs. The Quality Table could work to ensure (1) a common understanding of the WSIB’s procedural documents including those related to claims and employer accounts and (2) that signature WSIAT decisions are used to update WSIB’s adjudication guidelines. Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal already highlights noteworthy decisions on its website and in its annual report. Transforming these highlights into formal guidelines with elaborated reasoning could help inform the WSIB’s own reasoning and decision-making and minimize major differences between the two organizations.

The third is that the Minister of Labour, Training and Skills Development should work with the Attorney General to ensure that legal representatives participating in the workers’ compensation system have adequate training and are serving injured workers in an ethical way. The review heard from several stakeholders that a minority of paralegals and legal representatives in the workers’ compensation system risk harming the reputations of the significant number of paralegals and legal representatives who work hard on a daily basis to represent the interests of Ontario workers and employers.

The review heard that a small number of paralegals and legal representatives may be contributing to poorer system-wide outcomes that need to be addressed. The review in particular was told that claims that some may deliberately delay the appeals process in order to maximize their client base and in turn their earnings, others provide poor representation on behalf of clients in front of the WSIAT, or a small subset charge exorbitant contingency fees. These issues are beyond the scope of this review. But they came up frequently enough that it is important to raise them here. The Minister of Labour, Training and Skills Development should therefore work with the Attorney General and the Law Society of Ontario to ensure that paralegals and other legal representatives participating in the system have sufficient training and a clear understanding of their professional standards and obligations. This is important to protect the reputations of vast majority of paralegals and legal representatives who play a critical role serving injured workers and to ultimately ensure that workers are receiving the representation that they deserve.

2.7. Enhancing audits

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s risk-based approach for audits is intuitive. Random audits are inefficient. Targeted audits based on empirical metrics can be both more efficient and ultimately effective.

The reviewers met with WSIB officials to understand how the organization’s risk-based model and the identifiers and factors used to identify firms for audits. The identifiers and factors are a reasonable basis to guide audit activities. These include:

- a high percentage of claims that were not established by a Form 7

- a high ratio of abandoned/rejected claims

- a high percentage of no-lost-time claims that had high health-care costs high percentage of claims that were reported late

- extremely low injury rate compared to their rate group average

- Employment Standards Act conviction(s) published by the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development

But, as sensible as a risk-based auditing model may be, the WSIB must also recognize the potential risks associated with the new rate framework, such as employer confusion over compliance issues and the common perception that it will increase incidences of claim suppression. A significant reduction in audits in this context could not only miss possible changes in employer behaviour, but it could also harm public trust. Stakeholders in the review’s consultation expressed concerns over the reduction of auditing resources observed through a number of audits and auditors over the last few years.

This concern is heightened by the fact that the number of registered employers continues to rise and in turn the proportion of firms subjected to possible audits is falling. The result is that not only is the absolute number of audits (including both revenue-related audits and claim suppression audits) declining, but the relative number is projected to fall from 4.3% of Schedule 1 employers in 2015 to roughly 0.8% in 2020 (assuming average growth from the previous five years)

Changes to the auditing process are not occurring in a vacuum. The WSIB and the government must be more cognizant of the overall mix of operational and policy changes occurring during this period of transition and the cumulative impact on the incentives for employers. The combination of the implementation of the new rate framework and a decline in the absolute and relative number of audits risks sending the wrong signal about claim suppression and theoretically increases the potential for it to occur.

This would be a regrettable development for various reasons — namely, it would risk undermining the WSIB’s progress on establishing a claim suppression audit function and implementing the new administrative monetary penalty that can be applied to non-compliant employers. It risks a step backward based on perception and fact.

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board should therefore maintain staffing and resources to protect a statistically relevant number of audits through the implementation of the rate framework. It is beyond the capacity of the review to judge the optimal number of annual audits, but it should be much higher than planned for the foreseeable future. The goal should be to ensure that the number of claim suppression audits is statistically relevant in order to provide a credible basis to make judgments about the system’s performance including whether any operational or policy changes are required.

2.8. Strengthening the occupational health and safety ecosystem

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board is foundational to Ontario’s broader occupational health and safety ecosystem, but, as discussed in the previous section, it is not the only player.

The review frequently heard about the utility and value of the Office of the Worker Adviser and the Office of the Employer Adviser. Their combined budgets are less than $15 million per year, which is a small fraction of overall spending. Yet, by all accounts, these two small offices play a key role in educating their constituencies on WSIB issues and representing them throughout the process. The OWA in particular, has been forced to decline cases due to limited resources. A modest investment, therefore, could go a long way to ensure that workers and employers are better served in the system. This is particularly important in light of previous evidence that non-unionized workers involved in the system may be at risk of poor representation and high contingency fees.

Providing these organizations with additional funding would enable them to better address the current gap between supply and demand for their services. It could also help to reduce the burden on the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal by making the appeals process more efficient and effective. The proper level of incremental funding is, however, difficult to judge. The Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development should therefore consult with the Office of Worker Adviser, Office of the Employer Adviser and broader stakeholders to determine the right funding profile to increase the budgets of the Office of the Worker Adviser and the Office of the Employer Adviser.

A related issue is the available representation of unionized workers in the system. It is first important to observe that most unions do a tremendous job representing their members through the claims, adjudication and appeals processes. It is not an exaggeration to say that union representatives, by and large, are among the most experienced and knowledgeable stakeholders in the entire workers’ compensation system.

Yet there is a risk that exceptions to this rule not only poorly serve workers but also harm the reputation of unions who work hard to serve their members in the WSIB processes. Presently it is a legal obligation for unions to provide fair representation

on behalf of its members in the area of collective bargaining. They face no similar legal obligation with respect to occupational health and safety issues. Amending the Labour Relations Act to require that unions must provide mandatory representation for their members involved in WSIB cases would ensure consistency in support and representation among unionized workers in the province. It would also ensure that these workers have proper representation given that the OWAs statutory mandate focuses primarily on non-unionized workers.

2.9. Delivering more effective and outcomes-based prevention programming

The review heard from various stakeholders about the importance of prevention as part of an overall occupational health and safety strategy. But, as described earlier, there was also considerable discussion about placing a greater emphasis on measuring the effectiveness of prevention-related programming.

Better analysis of outcomes will require more real-time and future-oriented data. The current data sources tend to be lagging indicators (such as lost-time injuries) that, by definition, capture incidents that have already happened. This is exacerbated by silos between the WSIB, Ministry of Labour, Training, and Skills Development and the Office of the Chief Prevention Officer. Although there has been progress on working more collaboratively, there is still room for improvement. As an example, the WSIB and Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development only share data with the prevention office by request and it can take several weeks or even months. And, moreover, there are data gaps. The reviewers requested data from the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development on the occupational health and safety performance of firms that are not subject to mandatory coverage and learned such data did not exist. We do not know therefore if non-mandatory covered firms tend to have more or fewer workplace incidents.

The first step in improving Ontario’s prevention model is to better leverage data and evidence. The WSIB and the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development should provide data to the prevention office in real-time or as soon as it is available. The prevention office should also develop a set of leading indicators to better anticipate emerging workplace risks. More epidemiological data need to be captured to better understand the contributing factors related to different types of incidents and injuries. The Office of the Chief Prevention Officer should play a coordinating role between the WSIB and the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development to accumulate and analyse these various sources of data in order to better inform prevention-related programming and to ultimately measure its effectiveness.

The government should also revisit its model for how it delivers prevention-related programming. Presently the Office of the Chief Prevention Officer transfers approximately $80 million to six health and safety associations (HSAs) who are primarily responsible for delivering prevention services on behalf of the government. The funding is delivered in the form of annual transfer agreements.

The review heard from various stakeholders that the HSAs do an excellent job of providing highly specialized services. They have accumulated considerable expertise and specialization and are uniquely positioned to deliver certain types of advisory support and training. But the review also heard that new and emerging models (such as for-profit organizations) are also providing more general services and training in the marketplace, particularly to small and medium-sized employers.

The current funding agreements between the Office of the Chief Prevention Officer and the Health and Safety Associations, in effect, give them a public funding monopoly for both their specialized services and their general ones. The former area remains a market failure,

where they are the only options available given their capacity and expertise. But the latter is an increasingly competitive market.

The government should consider a new funding model whereby it continues to provide direct funding to the HSAs for their activities, which are specialized and unique, and run open competitions for more general services and training that HSAs as well as other organizations could apply for funding. It is beyond the capacity of the review to determine which specialized activities should continue to receive dedicated funding and which ones could be opened up to broader competition. The right mix between these two approaches would require consultations with unions, employers, the HSAs, and other stakeholders.

As part of this transition, the government should also consider providing three to five-year funding to the Health and Safety Associations as opposed to renewing them on an annualized basis. Additionally, increasing overall prevention funding, if it is more outcomes-based, can actually produce positive returns in the form of lower costs elsewhere in the system. If the government, therefore, pursues some of the structural reform proposed here, it may also consider increasing the overall prevention envelope in order to catalyse, support new and dynamic prevention-related models and partnerships and ultimately improve occupational health and safety in the province.

2.10. Improving the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s governance

The review was asked to examine the WSIB’s governance and executive structure to determine if any changes were necessary to improve the organization’s efficiency and effectiveness. The consultations heard a bit about these issues, but they were not common areas of concern for most stakeholders. Still, there are some areas that require further attention or improvement that could contribute to better governance at the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board.

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board’s executive structure — including the number of senior executives and their reporting relationships — does not seem out of the ordinary or a cause for concern. There has been some consolidation in the organization’s senior roles in recent months, for instance, that has reduced the number of personnel reporting directly to the president and CEO. Still, if the government wanted to further analyse the WSIB’s executive structure, it may consider hiring a corporate governance expert to conduct a review and provide advice on possible reforms based on best corporate practices.

The appointment of new directors to the WSIB’s board is one area where reform may be valuable. Presently appointments are made by the Minister of Labour. Training and Skills Development with limited consultation or engagement with the current of board of directors. The risk is that this process could produce competency gaps on the board, especially as a number of board terms will expire in the coming months.

One option would be for the Governance Committee of the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board to submit an evergreen list of skills and competencies that the board needs to fulfill its responsibilities. The list would represent private advice to the minister and could be regularly updated to reflect new and emerging competency needs. This would enable a two-way conversation between the WSIB’s Governance Committee and the minister and in turn, would provide the board with an opportunity to input into the appointment process and mitigate the risk of competency gaps.

A related reform is to the term lengths of WSIB directors. The recent experience has shown the potential for multiple directors to have expiration dates concentrated in a short period of time. The risk, of course, is the loss of institutional knowledge and continuity. This is a particular concern during this period of transition for the WSIB. The government should therefore consider staggered expiration dates to ensure that there is an orderly process for managing board turn-over.

Another possible reform relates to the Workplace Safety Insurance Act, 1997 legislative requirement for board meetings. The act stipulates that the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board's board of directors must meet at such a frequency that in no case shall more than two months elapse between meetings

A final area for further attention is the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board's real property footprint. The organization’s roughly 4,000 employees are spread across 15 offices in the province but approximately half are located in its Toronto office. The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board has been working with Infrastructure Ontario on a long-term strategy for its realty portfolio. It should engage an independent adviser (such as Infrastructure Ontario) to evaluate how the WSIB manages its real property portfolio and identify any possible efficiencies.

Footnotes

- footnote[78] Back to paragraph Workplace Safety and Insurance Board. (2019). Second Quarter 2019 Sufficiency Report

- footnote[79] Back to paragraph Alberta WCB Policies & Information (2018). General Policies: Funding Policies

- footnote[80] Back to paragraph Arthurs H. (2012). Funding Fairness: A Report on Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance System

- footnote[81] Back to paragraph Office of the Auditor General of Ontario (2009). 2009 Annual Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario: Unfunded Liability of the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

- footnote[82] Back to paragraph Workplace Safety and Insurance Board Operational Policy. (n.d.). Advanced Copy: Employer Classification: Single and Multiple Premium Rates

- footnote[83] Back to paragraph Workplace Safety and Insurance Board Operational Policy. (n.d.). Advanced Copy: Employer Accounts: Employer Level Premium Rate Setting

- footnote[84] Back to paragraph Workers Compensation Act, [RSBC 1996] Chapter 492

- footnote[85] Back to paragraph Bill 145, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board Coverage for Workers in Residential Care Facilities and Group Homes Act, 2017, Session 2, 41st Parliament, 2017

- footnote[86] Back to paragraph Ernst & Young. (2015). Workplace Safety and Insurance Board Value-for-Money Audit Schedule 2 Insurance Program Final Report. Internal Ernst & Young Report: unpublished

- footnote[87] Back to paragraph Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

- footnote[88] Back to paragraph Calculated using data from the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

- footnote[89] Back to paragraph Workplace Safety and Insurance Act, 1997 (S.O. 1997, c. 16, Sched A). Section 162