Initial Report: The Premier’s Advisory Council on Government Assets

Read the initial recommendations from the Premier’s Advisory Council on Government Assets on how Ontario can maximize the value of its key provincial assets, including the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), Hydro One and Ontario Power Generation (OPG).

Foreword

Overview

The Advisory Council on Government Assets was charged by the Premier to review the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), Hydro One and Ontario Power Generation (OPG) and to recommend ways to maximize their value to the people of Ontario.

In doing so, we took into account the government’s preference to retain core assets in public ownership and, in maximizing the value to the taxpayers, we also found ways to improve customer service and maintain an engaged employee workforce.

We were greatly assisted in our work by previous reviews done on these companies. We benefited from excellent cooperation from the companies themselves. We received numerous submissions from and met with many stakeholders. We found their comments well-researched and thoughtful. We also had constructive discussions with the unions representing workers in each of the companies. The Public Service of the Ontario Government has an enormous well of experience and capability that was made fully available to us.

We structured our review in two phases. Phase I, the results of which are included in this report, incorporated detailed reviews of the subject entities, stakeholder consultation and the development of our initial thinking on proposals for the future direction of each company. Phase II will incorporate further discussion and consultation on the proposals. This will further our goal of reaching agreement among the appropriate parties, leading to definitive recommendations to government for consideration in the 2015 Provincial Budget.

We have tried to conduct our review as transparently as possible. We approached our task with a genuine effort to have no preconceived answers to the issues raised, but to search for what is best for the people of Ontario, recognizing that we brought different visions and experience to the exercise. We are pleased that we are unanimous in our conclusions, which have also found broad agreement with the management of the companies themselves.

We have concluded that significant value can be added to the assets we reviewed within the parameters set by the government for this review. Indeed, we believe that the Province can, with the Council’s proposals, meet its key goals. It can retain all three core companies and significantly improve their performance. The Province can dilute its interest in some non-core assets where government ownership is not critical and where private sector involvement could facilitate more efficient electricity distribution. Our proposals would, over time, reduce the growth in electricity rates from those that would otherwise occur and keep liquor prices below the Canadian average, while improving consumer accessibility in a responsible fashion. Meeting these goals would free up $2 to $3 billion of funds to finance much-needed infrastructure investments without adding to the Province’s debt or increasing the deficit.

Premier’s Advisory Council on Government Assets

Ed Clark, Chair

David Denison

Janet Ecker

Ellis Jacob

Frances Lankin

Beverage alcohol

We examined the liquor distribution system in Ontario that centres around three quasi-monopolies — the LCBO as well as the privately-owned Beer Store (TBS) and off-site Winery Retail Stores (WRS). This system provides a highly-controlled distribution system for liquor that generally serves the consumer well, but limits accessibility and innovation. It is also a complex system with many interlocking parts that is prone to the creation of unfair value for those powerful enough to obtain certain rights.

We believe that the Province can retain the value of the existing beverage alcohol system while, at the same time, improving the customer experience, increasing access in a limited way and giving taxpayers a fairer share of the benefits of the system.

We considered selling the LCBO. There is a definite interest in the market for such an option, which offers simplicity and a large one-time financial benefit. However, we struggled with the concept of handing a monopoly over to a private owner. We were concerned that large outright sales of this kind in the past have proven to be far less attractive than they initially appeared. Privatization or sale to a private buyer would be a radical change to a system that actually works quite well and might require the creation of new regulatory systems. As far as consumer benefits are concerned, it is not evident to us that Ontarians would be materially better served by a privately operated LCBO. Further, any new owner would want to ensure that the monopoly they acquire is preserved. The Council believes that competition is a good thing, particularly for businesses like the LCBO which are not natural monopolies. Indeed, we would prefer to see some limited increase in competition rather than locking in a perpetual monopoly. Therefore, we rejected privatizing the LCBO.

We also examined the possibility of dramatically opening up the market structure currently controlled by the three quasi-monopolies in Ontario: the LCBO, TBS and the off-site Winery Retail Stores. Experience elsewhere suggests this would materially increase the number of access points, creating a more open marketplace but a more costly distribution system. Such a bold overhaul of the system would represent a radical change for the Province and would require a broad consensus that it is the right thing to do. Such a consensus does not appear to exist today.

We believe the LCBO should be retained in government ownership, but with the constraints of public ownership somewhat unshackled and a limited increase in competition to improve access and increase innovation. This would allow the LCBO to improve profitability and enhance service in a socially responsible way, essentially freeing up a public monopoly to act less like a public monopoly. This would include more effectively using the LCBO's buying power to lower costs. This should be done gradually. The initial focus of the LCBO will be to increase margins from suppliers and realize operational savings without affecting consumer prices. Should it be subsequently decided to raise prices, we would suggest that they should be maintained at below the national average.

Finally we believe, and the LCBO agrees, that there are a number of ways that customer choice and access can be improved and operations streamlined to improve profitability. The LCBO wants to update its website and create warehouse stores in major cities to carry alternative items not offered in standard stores. We also think the LCBO should explore the creation of specialty stores which emphasize craft beer or spirits, and should further orient certain locations to reflect the neighbourhoods in which they operate. As well, the online channel could make a broader array of products available than are carried in LCBO stores. These would support an aspiration for the LCBO to become a best-in-class liquor retailer. We expect to explore these ideas further with the LCBO in the next phase of our work.

The Council believes that the LCBO can be improved by better distinguishing between its true profit and the notional taxes it collects, as well as separately reporting its various businesses. The creation of this new disclosure framework will enable management to better represent and monitor performance and report on the implementation of our proposals, as improvements to the LCBO 's margins can be better evaluated.

In supporting, retaining, and improving the LCBO, the Council believes it is important to introduce more, even if limited, competition to provide more access as well as incentive to innovate. To this end, the Council is open in Phase II to exploring suggestions of how competition can be increased without undermining the fundamental economics and advantages of the monopoly system. Specifically, we would like to explore with craft brewers the possibility of opening a limited number of stores featuring craft beer from around the world. We would like to explore with the wine industry the possibility of opening new private stores offering both Canadian and international wines. Additionally, we would like to explore with distillers ideas regarding new sales channels.

In the case of the other distribution channels — the Beer Store and the off-site Winery Retail Stores — we do not believe as a matter of principle that the government should continue to foster a marketplace that provides unique benefits to these privately-owned quasi-monopolies. In our view there is unfair value flowing to the private sector owners at the expense of Ontario taxpayers. As changes are made to the LCBO to enable the Province to capture more value, we believe that similar adjustments should be made to the other quasi-monopolies.

We believe that the relationship between the provincial government and the Beer Store should be revised to ensure that Ontario taxpayers receive their fair share of the profits from the Beer Store. Consumers should not see an increase in prices as a result of this change. The Beer Store should be required to provide greater transparency, to ensure that costs are allocated equitably among suppliers, and to treat both owners and non-owners fairly, including with respect to the display of their products. The LCBO should be enabled to sell 12-packs and should increase its Cost of Service charge on beer.

In the case of the off-site Winery Retail Stores, only a select few wineries have off-site wine store licences. This seems unfair to the other producers. We also note that these wine channels permit the sale of what are essentially non-Canadian wines under the brand of a blended Canadian wine at very favourable tax rates relative to LCBO wine sales. This also seems unfair.

Given our bias to create more competition rather than less, we believe that wine stores, in some format, are a positive feature of the distribution system. As well, we recognize that stand-alone wine stores may not be able to sustain the same tax/mark-up system as the LCBO with its broader product assortment. We propose to engage the participants in a constructive dialogue to develop change that would reflect a fair tax system and continue to see strong demand for Ontario-grown grapes.

We need to find a balanced way to effect these changes so that value is not destroyed for the participants, but rather is more equitably shared. We believe that there could be a limited expansion of availability and would like to see an opportunity created for competitive distribution outlets to be established which would provide ongoing competition to the existing networks and force innovation.

In summary, we believe Ontario’s alcohol distribution system works relatively well. If consensus can be reached with the relevant parties and with the necessary political will, its limitations are largely fixable within the current construct by changing the behaviour of the three quasi-monopolies, adding some selective competition and making sure the public gets its fair share of profits.

Electricity

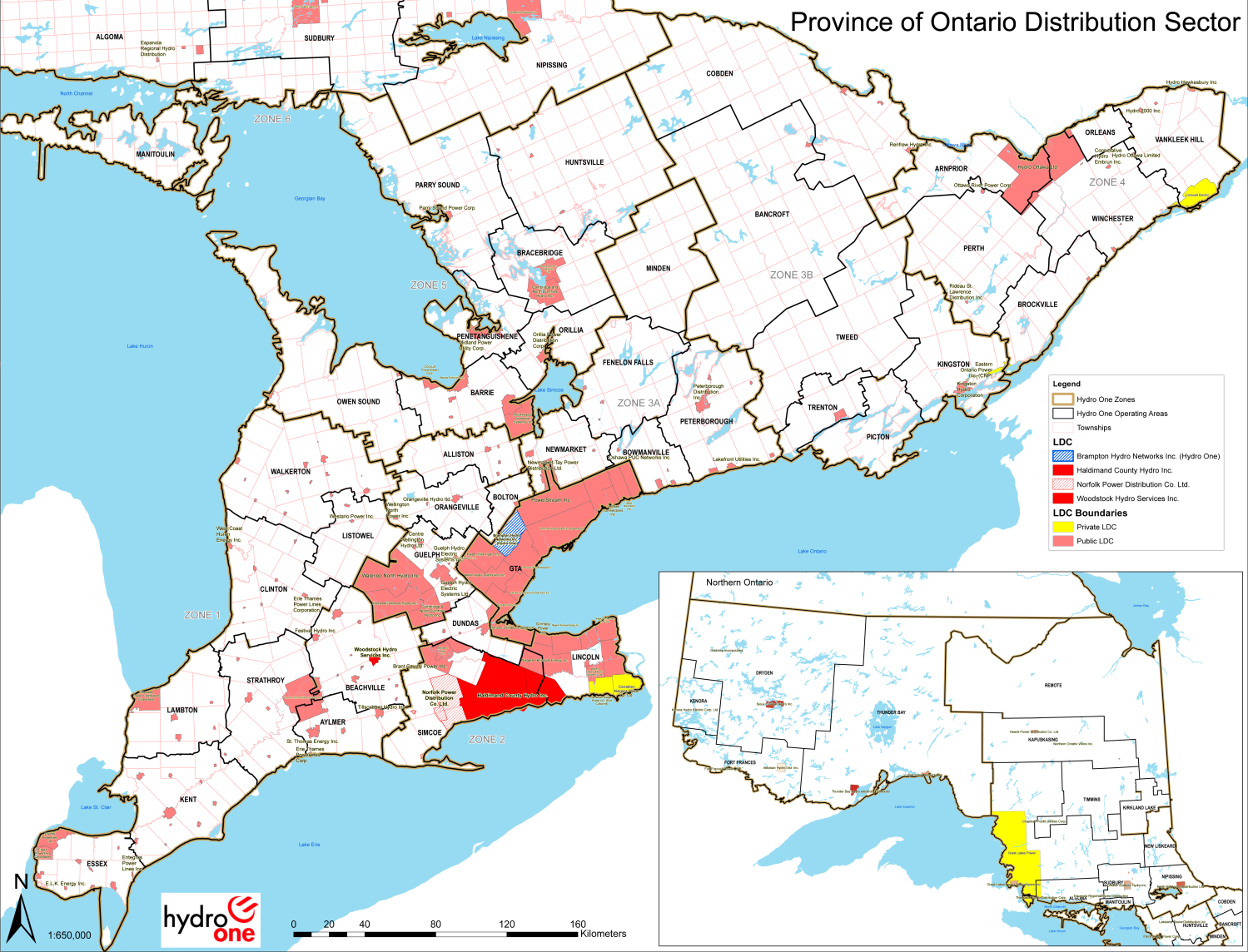

Hydro Onecomprises three main businesses within one company: a transmission business as one part of Hydro One Networks Inc. (Hydro One Networks), a large distribution business spread across the province as the other part of Hydro One Networks; and Hydro One Brampton Networks Inc. (Hydro One Brampton), a separate urban distribution business.

There are opportunities for operational improvements in both the transmission and distribution businesses. These have been recognized by management which is committed to exploring them. Many of these changes can be implemented without changing the current labour contracts. Other savings opportunities would require the cooperation of the unions and agreement of the shareholder. Where improvements can be made, the savings will accrue over time to electricity ratepayers.

Our view is that the transmission business is a well-run part of Hydro One with some opportunities to deliver savings on both capital and operating costs that should be pursued. While selling all or part of the transmission business would be attractive to the capital market, we believe this is an asset that, if retained in public ownership, can play a positive role in many aspects of electricity policy, including ongoing energy-sharing discussions with Quebec. Accordingly, we believe Hydro One transmission should remain in public hands as a core asset at this time.

We view the distribution business differently. There are huge challenges in Ontario’s local electricity distribution system. There are too many entities, some of them inefficient, that lack the capability and capital to modernize and adapt to the changing environment.

The electricity distribution sector was reviewed in 2012 by the Ontario Distribution Sector Review Panel. We agree with the Panel’s core conclusions — the need to foster consolidation and promote agile action in a changing energy world. Indeed, we believe these conclusions are supported by almost everyone in the industry, though not everyone agrees on how best to implement them. Ontario needs a more consolidated and efficient electrical distribution system. The system needs more capital, which is unlikely to be available from the public sector owners given other pressing needs.

The system also needs companies that can innovate and adjust nimbly to a very different energy world in the future. The current system fails that test.

Two entities that are key to breaking this logjam are Hydro One Brampton and the distribution business in Hydro One Networks. We propose that both be used, not to force consolidation but to catalyze it. Consolidation will facilitate efficiencies, reducing costs that in turn will reduce electricity rates from what they would have been. It will also improve adaptability of the system and create companies that can grow and create jobs. The Council would make this recommendation whether or not the Province needed money to fund new infrastructure. It is simply good energy policy. The Province should take action now as a catalyst and achieve savings over the long-term. We do not believe that the Ontario Government should divert resources from its priorities to fund consolidation of local distribution companies. Private sector capital is available to do this.

We are open to looking at different ideas as to how to encourage consolidation. One way would be to use Hydro One Brampton as a catalyst by merging it with one or more GTA-area distribution companies and then bringing in private capital to give it the financial capacity to undertake further consolidation. The Province could sell some of its interest in the company in a secondary offering along with the other existing owners, should government choose to do so.

We also recommend the separation of the transmission and distribution businesses now within Hydro One Networks into two entities. We would then propose that the government dilute its interest in that resulting distribution business by bringing in private capital. We would suggest that the Province initially retain a minority share (40% to 45%). This new company would then have the capacity to undertake further consolidations. These moves would create two champions of consolidation that would provide an entrepreneurial base for growth. We would expect other municipalities to respond either by joining these entities or seeking their own new partners — public or private. We would encourage both such moves.

Our preference would be to keep the distribution business in Hydro One Networks as a new separate distribution firm and not break it up. We recognize that there may be some limited circumstances where merging parts of the distribution business with specific municipal electrical utilities would foster further consolidation. But we would resist "cherry picking", as that would compromise the best outcome for taxpayers and electricity ratepayers. We would want to ensure that, if portions were to be sold, any sales would not reduce the value of the distribution business as a whole, and more importantly, not raise electricity rates from what they would have been. The Council is also open to other proposals and ideas that will come forward as part of Phase II.

We are very sensitive to the labour issues such a change of ownership raises. There are a number of rights that have to be respected and a number of concerns that will arise. We believe we understand these concerns but also believe that it is very important to have the right process to talk through and understand each party’s interests and concerns with the goal of finding sustainable, mutually acceptable solutions.

We also recommend that the government insist on provisions to protect against undesirable changes in ownership in the future. This would ensure that the Province can safeguard against unintended consequences from diluting its ownership.

We view Ontario Power Generationas being two distinct businesses — a complex and challenging nuclear business and a much more stable and straightforward hydro/thermal business. We focused mainly on the non-nuclear business — looking at possible operating improvements and whether there are assets that it would make sense to sell.

Cost savings in the hydro/thermal business are not overly large, but should be pursued. Similar savings are likely to be had in the much larger nuclear business. Management, which has been working on a business transformation initiative since 2011, is aware of opportunities and is committed to exploring them further.

OPG's portfolio includes assets — specifically its hydroelectric stations other than the large hydroelectric generating stations at Niagara Falls and on the St. Lawrence River — that could be sold to finance additional investments in provincial infrastructure. There is an active market for such assets.

However, a transaction involving these assets should not be OPG's first priority as it would involve a number of issues central to energy policy that would have to be resolved before reaching a conclusion that such a sale would be in the public interest. More important than pursuing a sale of hydroelectric generating stations, OPG faces a core issue: the refurbishment of the Darlington nuclear power station. This is paramount from a cost sustainability perspective. The scale and risk in this capital project dwarfs all other business issues at OPG. We recommend a laser focus on making sure Darlington comes on line safely, on time, and on budget. We also suggest that the government consider strengthening project management experience on OPG's board to help support the Darlington refurbishment.

To that end, we propose that OPG should consider creating, on a staged basis, an internal structure — as if they were two separate entities focused on their very different businesses. This could eventually lead to two separate organizations — a nuclear company with a Board that has predominantly large project management experience — and a non-nuclear company. However, moving aggressively now would risk diverting management’s attention from the core priority of the Darlington refurbishment and would also deprive the nuclear business of the financial support provided by the non-nuclear operations. Accordingly, any structural changes should be made over time.

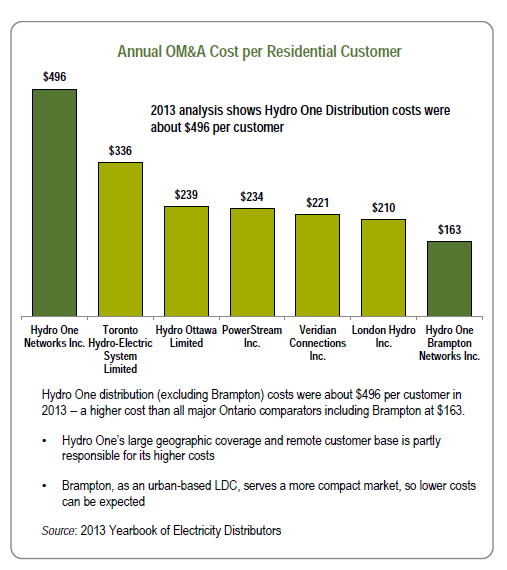

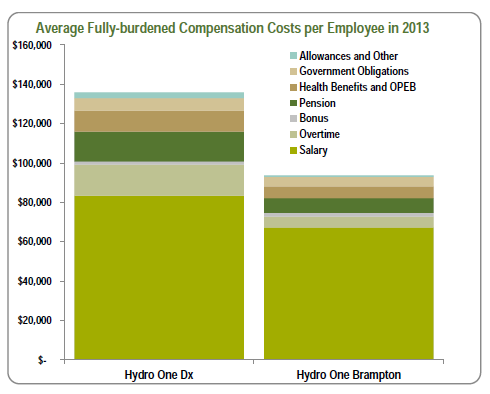

Cost savings that are attainable at Hydro One and OPG are relatively small unless both companies can alter their labour practices or modify their total compensation packages. Both have total labour costs that feature elements of above-market wages, benefits and pensions. Pension costs have recently been highlighted in the Report on the Sustainability of Electricity Sector Pension Plans (the Leech Report) and both entities operate under government-imposed restrictions that make them less productive than their private sector counterparts in heavy industries with field operations. These restraints impose a significant burden on electricity ratepayers and taxpayers.

To understand how we got here one has to understand a very long history of 'give and take' in bargaining. But, in today’s environment, the package of wages, benefits, pensions, and practices, in some cases, exceeds not only private sector standards, but public sector standards too. This is not true in all cases, especially with highly specialized and technical staff, so one must be careful not to make sweeping generalizations.

The Leech Report eloquently outlines the unsustainability of the pension plans in the electricity sector, including both OPG and Hydro One. Simply put: they are not consistent with public sector standards — and are not, in Special Advisor Leech’s expert view, stable.

We recognize that both union leaders and employees — at all levels — are equally concerned about ensuring the ongoing viability of these plans. We have a joint interest in finding a good, mutually agreed-upon solution. There has been broad agreement on a process to deal with this conversation. We recommend the government put urgency behind this initiative and ensure a coordinated government response.

If these companies are to stay and thrive in the public sector, modernizing labour practices to improve productivity is also critical.

Almost none of the potential improvements or restructuring at Hydro One or OPG will be possible without consulting and negotiating with the Power Workers' Union and the Society of Energy Professionals. These negotiations will be complex and challenging, but they are essential to long-term, sustainable operations. The current labour agreements were struck at the bargaining table and should be changed at the bargaining table. What is needed is to initiate a dialogue with management and the labour unions in order to agree on the facts and work together to understand the issues and the range of solutions.

Conclusion

We believe that our review has produced a sound, actionable framework to improve the operations of the entities we examined, to streamline the systems within which they operate, and to improve service to customers. This would free up funding for much-needed transit and transportation infrastructure investment.

Reducing government ownership in our electrical distribution systems through injecting private capital while retaining a minority share will help spur needed consolidation in the electrical distribution system to improve our electricity infrastructure.

At the same time, we estimate that between $2 billion and $3 billion, depending on market conditions at the time, can be realized and invested in Ontario’s transit and transportation infrastructure. These investments will create jobs directly and indirectly through investments in critical infrastructure which will remove impediments to economic growth. While the provincial government would get less ongoing income directly from these companies, the investments in economic growth will help mitigate this shortfall over time. In addition, this lost income would be more than covered from the savings generated by the improvements we are proposing for the entities we believe should remain publicly owned, including the LCBO.

The current beverage alcohol structure should continue — providing the benefits of a lower-cost, controlled model — but changes are needed to improve customer experience and returns to the Province. In addition, introducing limited competition will add further incentives to innovate.

All of this can be achieved without increasing the expected debt levels or increasing the expected deficit.

In the next phase of our work, the Council will engage with the companies and stakeholders to explore the proposals we are making in this report and seek to develop solutions that are pragmatic and, to the extent possible, supported by all parties.

Summary of council proposals

The following proposals, which have been developed based on our review and flow from the observations outlined in this report, constitute an actionable framework for change.

Beverage alcohol

LCBO

Ownership

- The Province should retain the LCBO.

- The current beverage alcohol market structure should be retained but opened up to greater competition.

Pricing and mark-ups

- The LCBO should move in a staged way to introduce a new pricing strategy, enabling it to use its buying power to reduce costs based on objective criteria, consistent with Canada’s international trade obligations.

- Ontario beverage alcohol prices should be maintained below the Canadian average.

- The LCBO should continue to review minimum prices.

Retail enhancement

- The LCBO brand should take advantage of its brand by associating it with certain products ("co-labelling").

- The LCBO store network should be expanded and differentiated by creating warehouse ("Depot") stores, converting some existing LCBOs to specialty shops which emphasize craft beer or craft distillery products, and orienting the product selection in certain stores to reflect their neighbourhood.

- The LCBO should develop into a best-in-class online retailer, fully integrating its website with its business to make a broader selection of products available to consumers and to provide suppliers, including those that don't have access to LCBO stores, access to the Ontario market. It should:

- make products available for online order ("click & collect");

- connect shoppers to the LCBO's warehouses; and

- create an on-line marketplace to allow any supplier in the world to register its products.

Labour

- The bargaining process must be respected; any changes to current agreements should be made at the bargaining table.

- Labour practices should be updated to improve productivity and to implement our recommendations.

Introducing competition

- Opportunities should be considered to introduce competition in a limited way, such as exploring with:

- craft brewers, the possibility of opening a limited number of stores featuring craft beer from around the world;

- the wine industry, the possibility of opening new private stores offering both Canadian and international wines; and

- distillers, the possibility of new sales channels.

Other proposals

- The LCBO should better differentiate its true profit from the mark-up it collects, as well as separately report its various businesses.

- The LCBO should realize the operational savings identified.

The Beer Store

- The LCBO's Cost of Service charges on beer should be increased.

- The LCBO should be enabled to sell 12-packs.

- Ontario taxpayers deserve their fair share of the profits generated from the Beer Store.

- Consumers should not see higher prices as a result of this change.

- The Beer Store should be required to:

- provide greater transparency;

- ensure that costs are allocated equitably between suppliers; and

- treat both owners and non-owners fairly, including with respect to display of their products.

- The possibility of opening a limited number of stores featuring craft beer from around the world should be explored with craft brewers

Winery Retail Stores

- The off-site WRS owners should be engaged in a constructive dialogue to achieve:

- a taxation system that is fair; and

- a set of changes that continue to see strong demand for Ontario-grown grapes.

- The possibility of opening new private stores offering both Canadian and international wines should be explored with the wine industry.

Electricity

Hydro One

General

- The Province should retain the transmission business at this time given its current policy role.

- Hydro One should work to realize operational savings identified over time.

- Hydro One should separate its distribution assets from the rest of its business.

- The Hydro One distribution assets should be used as a catalyst to encourage much needed consolidation and modernization of the electricity distribution system.

Distribution

- Private sector capital, rather than public funds, should be used to support the required consolidation of LDCs.

- The Province should dilute its interest in Hydro One Brampton by merging it with some other LDCs, including possibly with other GTA entities, based upon a pre-agreed business plan to bring in private capital to help grow and modernize the electricity sector.

- The transmission and distribution businesses of Hydro One Networks should be separated into two entities; the Province should dilute its interest in the resulting distribution company to a minority interest (40% to 45%) by bringing in private capital.

- The Council’s preference is to keep the distribution business whole to ensure a better outcome for ratepayers and taxpayers.

- Provisions should be used to protect against specific undesirable changes in the future ownership of these businesses.

- Any transaction should not create further upward pressure on rates.

- The current barriers and incentives, such as taxes, which impede consolidation should be reviewed during Phase II.

Labour

- The bargaining process must be respected; any changes to current agreements should be made at the bargaining table.

- Labour practices should be updated to improve productivity and to implement our recommendations.

- Rights must be respected and specific concerns should be addressed as a result of changes in ownership.

- A co-ordinated government response is required to achieve sustainable pension plans within Hydro One and OPG.

Ontario Power Generation

General

- A laser focus should be taken to ensure Darlington comes on line safely, on time and on budget.

- The government should consider adding more large project management experience to the OPG Board to oversee the Darlington refurbishment.

- OPG should work to realize operational savings identified over time.

- OPG should consider creating an internal structure over time as if there were two separate entities focused on their very different businesses: nuclear and non-nuclear generation.

Labour

- The bargaining process must be respected; any changes to current agreements should be made at the bargaining table.

- Labour practices should be updated to improve productivity and to implement our recommendations.

- A co-ordinated government response is required to achieve sustainable pension plans within Hydro One and OPG.

Introduction

Establishment of the Council

On April 11, 2014, the Minister of Finance announced a Council to provide advice on government assets, reporting directly to the Premier. The Council is made up of Ed Clark (Chair), David Denison, Janet Ecker, Ellis Jacob, and Frances Lankin. Establishment of the Council was also discussed in the 2014 Ontario Budget.

Mandate and principles

The Council’s mandate is to provide analysis, advice and recommendations on how best to maximize the value and performance of government business enterprises and other Provincial assets. This is intended to help the government deliver on its multi-year targets set out in the 2014 Budget. The government established three principles to guide the Council’s review. These were:

- The public interest remains paramount and protected;

- Decisions align with maximizing value to Ontarians; and

- The decision process remains transparent, professional and independently validated.

Terms of reference

We were asked to report to the Premier on the government business enterprises under review by the end of 2014 to contribute to the 2015 Budget process. The Council’s terms of reference provided the following guidance:

- Focus on core government business enterprises and operational agencies;

- Give preference to continued ownership of all core strategic assets to generate better returns and revenues to the Province;

- Advise the government on efficient governance and how best to achieve 'asset and income optimization' targets as set out by the government in ways that enhance services and value to the customers and recognize the need for highly performing engaged employees;

- Consider possible asset mergers, acquisitions and divestments if there is a strong business case and it would enhance value to the taxpayers of the province;

- Advise on possible changes to the corporate structure of the government business enterprises, including private-public sector partnerships;

- Review and comment on possible directions and agency proposals and business plans; and

- Take into account the protection of the public interest, including providing for an appropriate legislative and regulatory framework.

Scope of our review

Within our overall mandate to review government assets, we were specifically directed to examine three government business enterprises — the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, Hydro One, and Ontario Power Generation. They form the foundation of the government’s participation in the beverage alcohol sector and the electricity sector. Within the beverage alcohol sector are three major retail entities:

- LCBO

- Beer Store

- Winery Retail Stores

Although neither the Beer Store nor the Winery Retail Stores are government business enterprises, they are regulated by the government and are part of the province’s beverage alcohol system. As such, the Council concluded that it was impossible to consider the LCBO's place in the beverage alcohol sector without acknowledging the Beer Store and off-site Winery Retail Stores as competitors and comparators with the LCBO.

In the electricity sector, there are two government business enterprises:

- Hydro One

- Ontario Power Generation (OPG)

Given the short time frames associated with the Council’s advice to government and the size and complexities associated with nuclear power generation, we restricted the scope of our OPG review to its non-nuclear operations.

Our perspective

As we began our work, we set ourselves a goal to craft our advice in a way that would:

- Retain core enterprises within public ownership;

- Possibly divest some non-core assets to support investment in much-needed and productive infrastructure without adding to the Province’s overall debt or increasing the deficit;

- Improve both business performance and customer service in the subject entities while not increasing commodity costs to consumers.

We recognized from the outset of our work that all the entities operate within a tightly constrained regulatory or policy regime; furthermore, this is by no means the first time these sectors and entities have been reviewed.

Both the beverage alcohol and electricity sectors have been studied intensively over several decades. A number of studies have proposed different structures and operating models. Some of the operational recommendations of these studies have been implemented, but most strategic and transformational recommendations have not.

As we embarked on our review, we asked some basic questions:

- Could these publicly-owned companies be better run?

- Could they be more customer-focused?

- Are all the companies' assets truly core to their mission?

And because these publicly-owned companies (like any company in the private sector) have limited capacity to act, is there a set of practical steps that are within their capacity that would unlock value?

Our bias was clearly towards the do-able. It is easy to come up with dramatic shifts in strategy — but such shifts would require deep cultural changes in the organizations, and broad societal support to make them happen. We prefer a more measured approach — each step of which improves what we have and actually gets things done rather than adds this report to the list of earlier reports never implemented.

The Council was also guided by the government’s desire to find the financial capacity to fund needed transit and transportation infrastructure in the province.

We started from the premise that all three entities under review would have opportunities to realize value and improve performance as would almost any business in Canada, whether public or private. However, we recognized that in many cases the entities may have been constrained by the fact that they are government-owned; in practice, they operate in an inherently political environment. But we kept several things in mind.

As mentioned, government’s preference is to retain ownership of core assets. The Council also believes that rushed asset sales are not in the public interest. Any sale must be a carefully staged and competitive process.

We asked whether the government is, indeed, the best owner of these assets, and the purpose served by government ownership. Would a company — in private hands — be better able to serve the consumer or electricity ratepayer? Would bringing in the private sector unshackle a company, allowing it to grow and create jobs?

These assets all earn income for the Ontario government — income that is important given its deficit position. But the proceeds of any asset sale are unlikely to be reinvested in new direct income-generating assets. The new infrastructure assets may greatly benefit Ontarians and add enormous value to the provincial economy; this, in turn, would create income indirectly, through increased economic activity for the provincial government in the medium-term. But in the short-term, a loss of income is likely. The Council was very mindful of that impact. So, to offset any loss of income, it became even more critical to ensure better performance of the assets retained by the government.

The Council agreed that swapping ownership in infrastructure assets can make sense. But it is important that any funds raised are used to invest in other assets that deliver high societal or economic returns to the province. The government has made clear that funds raised in this process will be used to invest in transit and transportation infrastructure. Better infrastructure will allow the economy to grow faster, create more jobs, and increase both competitiveness and productivity. In addition, of course, there are jobs directly created by undertaking the investments.

Finally, we set out with a view that the Government Business Enterprises we were reviewing have, in most cases, adapted relatively successfully to their operating environment. The three management teams and boards have identified areas for improvement and implemented several of those changes. We engaged each of the organizations in our work so that we could explore opportunities collaboratively and, ideally, come to a collective view on how to effect change that is meaningful and achievable.

Our approach

We structured our review in two phases:

- Phase I incorporated detailed reviews of the subject entities, consultations with stakeholders and the development of our initial thinking on proposals for the future direction of each company. These are included in this initial report for consideration in the Fall Economic Statement; and

- Phase II will incorporate further discussion and consultation on the proposals, which would further our goal of reaching agreement among the appropriate parties, leading to definitive recommendations to the government for consideration in the 2015 Provincial Budget.

As we move forward, we will continue our commitment to a collaborative and transparent process as we work out specific ways to implement our recommendations.

Phase I. In Phase I, we undertook two main streams of work — detailed reviews of the entities in which we were supported by professional consulting expertise, and meetings with selected industry associations and stakeholders who are either employed by, regular clients of, partners of, or competitors with the three Government Business Enterprises.

The major work streams in each of the three companies involved an analysis of each organization and its operations, investigating issues and then developing and evaluating options for performance improvement, cost savings, and/or the optimization of asset value. We engaged a number of advisors and consultants to assist us in this work.

We met with a wide range of stakeholders, among them all the business entities involved and the oversight ministers. We met with representative stakeholders, including unions, in both the beverage alcohol and the electricity sectors. The Council also received a number of formal submissions in the course of our review, and we very much appreciated the thoughtful and constructive input we received through this process.

The beverage alcohol sector

Overview

The beverage alcohol sector in Ontario generated total retail sales of about $7 billion in 2013–14, of which about $3 billion went to the Ontario government through:

- a dividend from the LCBO ($1.74 billion);

- taxes on beer sales through the Beer Store and on-site manufacturers' stores ($524 million);

- taxes on wine sales through on- and off-site Winery Retail Stores ($33 million); and

- the provincial portion of Harmonized Sales Tax on sales at retail stores and licensed establishments ($650 million).

The Ontario system is dominated by three retail networks that are owned either by the government (LCBO) or producers (the Beer Store and Winery Retail Stores) and that have a quasi-monopoly on beverage alcohol wholesaling and retailing in Ontario:

- The LCBO is owned by the Province and operates 639 stores across Ontario. The LCBO also authorizes 217 Agency Stores, which are privately operated and provide retail access to consumers in less densely populated areas.

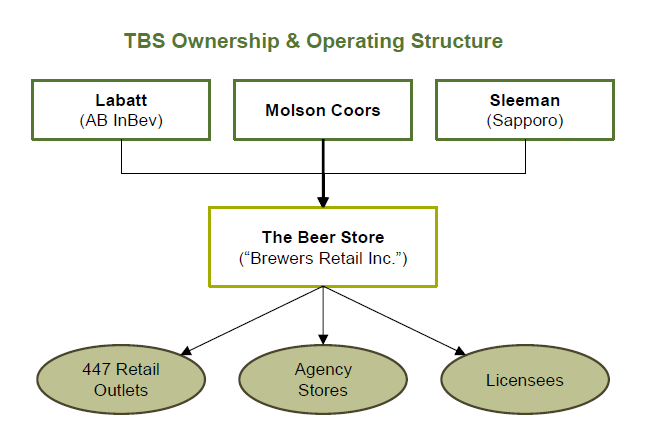

- Brewers Retail Inc. (BRI), which operates as the Beer Store, is owned by a consortium of three foreign-owned brewers, and has 447 stores across the province.

- Off-site Winery Retail Stores are owned by six wineries and retail only their own products at 292 locations across the province.

In addition to the channels listed above, local producers can sell their own products at on-site manufacturers' stores located at their point of production. Along with the LCBO and the Beer Store, authorized producers are also allowed to sell their products to licensed bars and restaurants, referred to as licensees.

Certain other provinces have modified their systems in recent years:

- Alberta is the only Canadian province or territory to fully privatize the retailing of beverage alcohol. A provincial agency retains control over the importation of alcohol into the province, and hires private companies to warehouse alcohol on its behalf.

- British Columbia is an example of a Canadian province with side-by-side public and private liquor stores selling a full range of wine, spirits, and beer. Private stores purchase liquor from the provincial agency at a discount to retail price, which was initially set at 10%. Today, that discount ranges from 16% to 30% for certain stores.

- Quebec also employs a hybrid model. The provincial agency is the only entity permitted to retail spirits and wine bottled outside the province, with wine bottled in Quebec and beer sold in private channels throughout the province, at convenience and grocery stores, as well as specialty retailers.

The public policy rationale for the design of Ontario’s system was originally — and largely remains — to control the distribution and sale of beverage alcohol. As such, government plays a strong role in the sector. Since the inception of the system in the late 1920s, government policy has focused on balancing consumers' desire for access to beverage alcohol against the social responsibility of mitigating its harmful effects. The Province has focused on managing the health hazards of beverage alcohol by limiting retail outlet density and controlling points of sale, preventing broader retail availability. This public policy issue is not unique to Ontario or Canada. Few governments treat beverage alcohol as simply a normal consumer product.

Many pieces of legislation, regulations and agreements govern the import, sale and transport of alcohol in Ontario, including:

The Importation of Intoxicating Liquors Act (Federal) assigns importation authority for beverage alcohol to provincial and territorial authorities.

The Liquor Control Act empowers the LCBO to retail beverage alcohol and to regulate warehousing and pricing and authorizes BRI and the basis for on-site brewery, winery, and distillery stores to sell their products to the public.

The Liquor Licence Act regulates responsible use, licensee sales and service requirements as well as establishes manufacturing and distribution conditions and legislation for marketing and advertising practices.

The Alcohol and Gaming Regulation and Public Protection Act ("AGRPPA") establishes the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario ("AGCO") and provides legislation for beer and wine taxes and their collection.

The Beer Framework Agreement, signed in 2000 between the LCBO and Brewers Retail Inc., acts as an operating agreement between the two entities. It gives the Beer Store exclusive rights to sell beer in formats larger than a six-pack in communities with a TBS location, and prevents the LCBO from wholesaling beer carried by TBS to licensees. The Beer Framework Agreement can be terminated with six months' notice.

International Trade Agreements, including the Beer Trade Memorandum of Understanding between Canada and the U.S., North American Free Trade Agreement, the Agreement between the European Community and Canada on Trade in Wines and Spirit Drinks, as well as the proposed Comprehensive Economic & Trade Agreement and Trans-Pacific Partnership, require treatment of imported products that is no less favourable than that accorded to domestic products.

LCBO

Background

The LCBO is a government business enterprise that has a monopoly for the wholesaling and retailing of spirits and imported wine and competes with Winery Retail Stores for Ontario wine sales as well as the Beer Store for beer sales.

The LCBO provides a direct return to the Province through an annual dividend. This amounted to $1.74 billion in 2013–14, and has grown at a compound annual growth rate of about 5.5% since 1994.

The LCBO is by no means a conventional liquor wholesaler and retailer. It operates in a complex environment that has shaped the way the organization operates today.

LCBO

Regulatory Framework / Mandate

- Liquor Control Act is guiding legislation

- Balanced mandate between social responsibility and financial returns to Province

- Performs a number of activities because it is a part of government (policy, communications, Freedom of Information, French Language Services, etc.)

- Suppliers and other stakeholders routinely appeal to government for changes to the LCBO

Governance

- Publicly-appointed Board of Directors has authority to execute operations under LCA

- Reports to Minister of Finance

- In practice, financial decisions are made in collaboration with the Ministry of Finance

Labour Relations

- Single union – Ontario Public Service Employees Union

- Approximately 90% of workforce is unionized

- Average age of approximately 45 years; average age of permanent employees within union of over 50 years

- Staff turnover of less than 5%

Market Dynamics

- Monopoly on spirits; near monopoly on wine

- Competitor to the Beer Store for beer sales

- Product pricing set on ‘cost plus’ basis

- Intersects with public policy goals; LCBO provides incremental support to suppliers

Our approach

The Council worked closely with LCBO management to understand their perspective and explore opportunities to improve performance. We were also assisted by consulting teams that undertook a focused diagnostic review to identify potential operational and profit improvements.

Our observations

General. Ontario’s beverage alcohol system is a product of its long history and has evolved in piecemeal fashion over the years. It may well be that, given a clean sheet, no one would design a system to operate as this one does. Given its status and history, it is hardly surprising that the LCBO neither resembles nor operates like a traditional private-sector wholesale/retail organization.

That said, the LCBO has evolved significantly over time, particularly over the past decade or so. Substantial investments in stores and improved customer experience, as well as a broad product assortment and a large footprint across Ontario, mean that consumers are generally well served by the organization. Currently, 90% of the Ontario population lives within 5 km of an LCBO or agency store. Operationally, allowing for the constraints within which it operates, the LCBO has made substantial strides in transforming itself from a government control mechanism into a modern wholesale and retail organization.

All in all, we found that, despite the constraints put upon it by government policy and labour agreements, the LCBO provides Ontario consumers with a very broad and convenient network, a sophisticated retail experience and a significant assortment of products that are, on average, priced below the Canadian average.

Ownership of the LCBO. One of the central questions we addressed was whether the Province should continue to own and operate the LCBO or whether it should be privatized in some manner. There have been arguments made over the years that the proper role of government is to regulate and oversee rather than to own and operate. In light of this, we considered the privatization options carefully.

We considered selling the LCBO. There is a definite interest in the market for such an option, which offers simplicity and a large one-time financial benefit. However, we struggled with the concept of handing a monopoly over to a private owner. We were concerned that large outright sales of this kind in the past have proven to be far less attractive than they initially appeared. Privatization or sale to a private buyer would be a radical change to a system that actually works quite well, requiring the creation of new regulatory systems. As far as consumer benefits are concerned, it is not evident to us that Ontarians would be materially better served by a privately operated LCBO. Further, any new owner would want to ensure that the monopoly they acquire is preserved. The Council believes that competition is a good thing, particularly for businesses like the LCBO that are not natural monopolies. Indeed, we would prefer to see some limited increase in competition rather than locking in a perpetual monopoly. Therefore, we rejected privatizing the LCBO.

We also examined the possibility of dramatically opening up the market structure currently controlled by the three quasi-monopolies in Ontario: the LCBO, TBS and the Winery Retail Stores. Experience elsewhere suggests this would dramatically increase the number of access points, creating a more open but more costly distribution system. Such a bold overhaul of the system would represent a radical change for the Province and would require a broad consensus that it is the right thing to do. Such a consensus does not appear to exist today.

However, in supporting, retaining, and improving the LCBO, the Council believes it is important to introduce more, even if limited, competition to provide more access as well as pressure to innovate. To this end, the Council is open in Phase II to exploring suggestions of how competition can be increased without undermining the fundamental economics and advantages of the monopoly system. Specifically, we would like to explore with craft brewers the possibility of opening a limited number of stores featuring craft beer from around the world. We would like to explore with the wine industry the possibility of opening new private stores offering both Canadian and international wines. Additionally, we would like to explore with distillers ideas regarding new sales channels.

Maintaining government ownership of the LCBO does not imply a continuation of the status quo — far from it. Working closely with management of the LCBO, we identified significant opportunities to create greater value and improve performance. In essence, we endeavoured to find ways that the LCBO, as a public monopoly, could act less like a public monopoly. If it turns out that this cannot be done, our bias would be to look again at ways to introduce even more competition than we are suggesting today. As previously stated, we believe that competition is a good thing.

The LCBO operates under significant constraints in both pricing and mark-up. Contrary to what many Ontarians believe, the LCBO does not actually set retail liquor prices in the province. Within specified price ranges, the LCBO applies a fixed mark-up (generally a percentage) to a supplier’s quote to determine the end price to the consumer.

The government imposes only two pricing constraints on suppliers:

- a requirement that minimum prices be charged for various categories of alcohol, an important tool for the Province’s social responsibility mandate; and

- a requirement for uniform retail prices for that product, no matter where it is sold in the province or through which channel.

While the LCBO seeks the best value for consumers within these price bands, the LCBO does not establish either wholesale or retail prices for products it buys and sells — it simply derives its operating margin from the fixed mark-up. It is important to understand the incentives that this system creates. Since the LCBO's mark-up for wine and spirits is based on a percentage of the supplier’s quote, cost concessions by suppliers actually reduce the LCBO's profits. As a result, there is little incentive for the LCBO to use its buying power to reduce the price it pays to suppliers and, by extension, the price it charges to consumers. Further, if the LCBO sees an opportunity to increase prices, it cannot do so without suppliers charging a higher cost.

Consumer prices: In our review of pricing at the LCBO, we excluded beer, given the Beer Store’s dominant market position. One might expect that wine and spirits prices in Ontario would be higher than they are in jurisdictions where more competition exists. However, our analysis indicates that this is not the case. In developing our price data, our consultants:

- examined self-reported provincial data aggregated by the Canadian Association of Liquor Jurisdictions (CALJ), which provides price data for an agreed-upon set of 42 wine and spirits products, four times per year; and

- conducted independent price checks of 43 wine and spirits products at seven government- and 16 privately-operated liquor retailers in Alberta, British Columbia and Quebec.

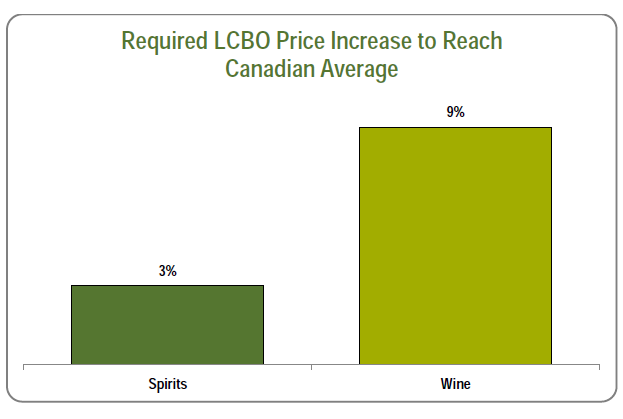

The CALJ data indicate that beverage alcohol prices in Ontario are generally below the Canadian average. The independent store visits turned up a similar result when comparing Ontario with Alberta, British Columbia and Quebec. The chart below illustrates the price gaps. Based on the CALJ data, the LCBO would have to increase prices for spirits by 3% and wine by 9% to reach the Canadian average.

Reducing cost of goods sold: The LCBO is one of the largest purchasers of beverage alcohol in the world, yet has too little incentive to use its considerable purchasing power to reduce the cost of goods sold (COGS) as any typical commercial wholesaler or retailer would.

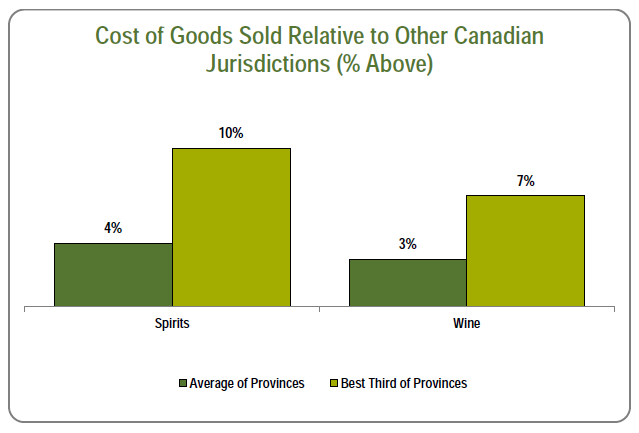

Using data from CALJ, we analyzed prices paid by the LCBO to wine and spirits suppliers for 42 products, comparing those to other Canadian jurisdictions. Although this limited set of items did not encompass the entire assortment available at the LCBO, we found the results striking as, in many cases, suppliers received higher prices in Ontario than they did in other Canadian jurisdictions. As illustrated in the chart below, the cost of goods sold is higher than the average for all provinces

(the darker columns on the left) – by 4% for spirits and by 3% for wine. Compared with the lowest-cost third of the provinces (the lighter columns on the right), costs are 10% higher for spirits and 7% higher for wine.

In essence, in Ontario, products are purchased from suppliers at above-average costs, yet the LCBO sells the same products to consumers at below-average prices. Two factors largely explain this:

- Cost: the distribution system in Ontario is highly integrated and much more efficient than those of other jurisdictions; and

- Margin: under the fixed mark-up structure, the LCBO cannot maximize its profits, effectively transferring value from taxpayers to suppliers.

Nowhere is this latter point more apparent than with minimum prices. The combination of a relatively high price floor and a fixed mark-up structure forces prices paid to suppliers upwards. The effect of this reverberates throughout the LCBO's product assortment, as these higher minimum prices put upward pressure on other products within the same category. We do not believe it is good policy for suppliers to receive windfall profits as a result of a social policy. As a result, we have discussed with the LCBO opportunities to competitively procure products that are listed at the minimum price. These initiatives would be based on objective criteria and consistent with international trade obligations.

The current minimum price for wine is not effective, as only a small portion of wine sold in the province changes hands at or near the minimum price. Given the role minimum prices play in encouraging responsible consumption, we note that wine has the lowest minimum price per litre of absolute alcohol content, substantially trailing beer and spirits. The government should consider raising minimum prices closer to real market levels and be prepared to move minimum prices up even further if warranted.

This should be done in a way that allows the LCBO to capture the resulting increase in profits.

There are opportunities to improve the customer experience within the existing store network. Our discussions with LCBO management and our review of the retail experience in other sectors and jurisdictions led us to conclude that the LCBO can improve the customer experience in a number of ways. These represent meaningful opportunities for the LCBO to increase margins while, at the same time, delivering better value for consumers. These include:

- Co-labeling: The LCBO could do more to monetize its strong brand by associating it with specific products, to the benefit of both its customers and the LCBO. Tags on products indicating "Buyer’s Picks" — combined with preferential shelf space for these goods — could help consumers in their buying decisions. As these opportunities would be auctioned to domestic and foreign producers for specific products, this would provide strong financial returns for the LCBO. Both co-labeling and preferential shelf space are examples of non-discriminatory ways to increase margins.

- Store network: Virtually all new LCBOs are large visually-appealing stores. This enables the organization to offer meaningful shelf space to local wineries and craft brewers and to allocate its high retail labour costs across a larger footprint with higher sales. We have worked with the LCBO to find ways in which it can enhance its overall store portfolio by creating variations within its network. Opportunities identified include:

- Craft and Cider Destination Stores: Elevating Craft. The LCBO now has a small number of 'Destination Stores' that carry a significantly broader selection of local wines. We believe that this store-within-a-store concept can be replicated to create certain specialty Craft Beer and Cider Destination Stores. These would be of interest to consumers, while also representing a meaningful opportunity for craft brewers.

- Craft Distillery Sections: Empowering Licensees. Craft distilled spirits represent a small but increasingly popular market segment. To address this, the LCBO has proposed setting up Craft Distillery Sections in specific stores across the province. This specialized shelf space would enable licensees to purchase craft distillery inventory in small quantities through the LCBO store network, while highlighting this growing segment for retail consumers as well.

- Niche Stores: Meeting Local Consumer Demand. The LCBO could create specialty boutiques in specific stores that better cater to the tastes and demands of the local community. For example, a store on the Danforth in Toronto could specialize in Greek wines and spirits while in Little Italy customers could find an exclusive selection of Italian wines and beers. These niche stores, while better serving their communities, could become popular destinations for many customers.

- Depot Stores: A New Buying Model. We discussed with the LCBO a design for a select number of new stores that would offer a limited selection of products sold by the case at all price points. These "LCBO Depot" stores would be much more basic in nature and would sell competitively-procured products not currently carried by the LCBO, emphasizing great value for customers.

The LCBO could improve customer experience through an integrated online platform, becoming a best-in-class online retailer. Although the LCBO is introducing a new website and digital platform, we — along with the LCBO management team — believe that more can be done to foster an integrated consumer experience. Current proposals being explored include:

- Online Retailing of In-store Assortment: Click & Collect. Stores would be integrated with an online 'click and collect model' that would enable customers to order products online for pick-up at their local LCBO. We believe this would represent a significant improvement for customers. When combined with new initiatives such as Depots, it would expand the assortment of products available and provide a different type of retail experience.

- Online Retailing of Warehoused Products: Private Stock. Today, LCBO warehouses contain thousands of products, many of which are held for agents and sold exclusively to licensees. These products are not available in LCBO retail stores. We believe the LCBO can use its online platform to create a new sales channel for these products; consumers could buy these products through the LCBO website and pick them up in their local LCBO store. This would enable agents and suppliers to benefit from a new sales channel and provide consumers with access to niche products.

- Open Marketplace: Online Retailing of Any Products. Even with the above initiatives, consumers in Ontario will have access to only a small fraction of the beverage alcohol produced worldwide. We believe the LCBO can use its online platform to create an open marketplace on its website, allowing suppliers and agents around the world to list products for consumers to purchase for pick-up at their local LCBO store. The marketplace would be open to all producers, and would also be an interesting opportunity in the context of interprovincial sales.

Accountability and measuring performance. Although many — including the LCBO management team — view the organization as an integrated entity, we see the LCBO as a business with three core segments:

- Retailer: the largest liquor retailer in Ontario by points of sale and total dollar sales;

- Wholesaler: one of the largest beverage alcohol buyers the world;

- Private contractor: engages with private-sector agency store operators and authorizes wineries to deliver products directly to licensees.

Each of the businesses has its own unique dynamics. Almost certainly, performance differs across the three areas. However, the LCBO does not currently assign accountability or measure performance in a way that reflects this.

In addition, sales of beverage alcohol within Ontario through non-LCBO channels are subject to commodity taxes levied by the Province. LCBO sales, however, are not subject to these, as they are effectively included in the business’s mark-up.

There are a number of issues with the above, including:

- Overstatement of profits: by combining notional taxes with business profit, the LCBO creates a false sense of profitability for both management and employees. The LCBO, like most retailers, is a thin margin business. By not presenting itself as such, it is more difficult for the organization to have the appropriate cost orientation.

- Misallocation of profits: the LCBO now allocates the organization’s wholesale profit and notional taxes to its retail channel, risking suboptimal business decisions.

The Council believes that the LCBO can be improved by better distinguishing between its true profit and the notional taxes it collects, as well as separately reporting its various businesses. The creation of this new disclosure framework will enable management to better represent and monitor performance and report on the implementation of our proposals, as improvements to the LCBO's margins can be better evaluated.

Operational effectiveness. We examined all areas of the LCBO's operations and generally found them to be well designed and operating efficiently within their constraints. However, as with any business, there is room for improvement in some areas. We, together with management, identified opportunities within:

- work practices and scheduling;

- efficiency of warehouse-to-store delivery;

- marketing programs; and

- freight savings.

The LCBO management team is committed to pursuing these opportunities.

Labour costs. Labour accounts for nearly half of the organization’s operating expenses. The LCBO has about 7,700 full- and part-time employees, of which about 7,000 are represented by the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU).

The collective agreement between the LCBO and OPSEU establishes labour rates and work practices that have a significant impact on how the LCBO operates. While these reflect benefits that the workforce has achieved at the bargaining table, they also impede the organization’s ability to modernize and streamline its operations.

Our consulting review compared the LCBO's wages to several comparable private- sector companies (Canadian Tire, Shoppers Drug Mart, and The Source), and determined that, on average, LCBO wages are about 90% higher than those paid by typical Canadian retailers. Further, LCBO staff and casual employees earn more than their counterparts at the Beer Store (the middle columns in the chart below), which is also unionized.

This difference was not uniform across all job categories:

The gap between staff wages and those of store managers is much narrower in the LCBO (the dark columns on the left) than in the peer group (the columns on the right). Most LCBO store managers are not unionized, and have had their wages frozen by government for the past six years, while wages for unionized assistant managers and staff have increased annually with government support over that same time period. This wage compression limits the ability of the organization to promote from within. In 30 extreme cases within the LCBO store network, a non-unionized store manager actually earns less than a unionized assistant store manager.

Perhaps the starkest example of the constraints that the LCBO's labour costs impose on the organization relates to staffing on Sundays. While full-time staff are paid an hourly rate of $26, these employees earn one-and-a-half times their regular rate of pay on Sundays. When benefits are included, this results in a fully-loaded cost per employee of about four times the wage rates of our private sector peer group. This makes the cost of having stores open on Sunday prohibitive and out of step with other competing channels.

The existing collective agreement provides LCBO management with some measure of flexibility to manage its operations, assign and re-assign workers and determine the complement of the workforce. The LCBO has increasingly relied more heavily on the use of casual staff as a tool to manage scheduling and costs more efficiently. However, other provisions exist that inhibit management’s ability to reorganize and restructure the workplace to improve operational effectiveness.

The current labour agreements have evolved over time as part of the give and take of the bargaining process. We believe that this is how they should be changed in the future. It is in the interest of all stakeholders that the LCBO be able to evolve as a customer-focused organization. If it cannot adapt, pressures will grow to increase competition even further than what we have proposed. We would therefore recommend that the primary focus be on addressing things that make it more difficult for the LCBO to operate as a customer-focused retailer and to implement our recommendations. In addition, we believe that it is important that any future wage increases remain consistent with the government’s labour strategy for the broader public sector.

The Beer Store (TBS)

Background

The Beer Store was originally established as a brewers' co-operative in 1927. Today, it is owned by three brewers — Labatt (owned by Anheuser-Busch InBev), Molson Coors and Sleeman (owned by Sapporo):

Total beer sales to consumers and businesses in Ontario are about $3 billion annually, almost 80% of which is accounted for by TBS. The Beer Store has an open-listing policy; any brewer can list products in TBS stores, provided it pays certain one-time and ongoing fees. In addition, TBS operates the Ontario Deposit Return Program (ODRP) on behalf of the government, providing a network of locations where consumers can drop off empty containers and redeem their deposits.

TBS employs about 7,000 people in Ontario. The three owners also operate breweries in the province with an estimated 1,300-1,600 manufacturing jobs. The craft brewers employ more than 1,000 people in Ontario.

The retail price of beer in Ontario contains a complex mix of taxes or mark-ups, levies and charges, depending on where the product is sold.

- Like all other beverage alcohol products, beer prices are set by the supplier and are subject to minimum and uniform pricing rules.

- The LCBO mark-up, which applies to imported beer and domestic beer sold in the LCBO, is set equal to the Beer Tax, which is applied to domestic beer, to ensure compliance with trade obligations. This value is a fixed dollar amount per litre.

- To cover expenses associated with selling beer through their networks, the Beer Store and LCBO charge brewers Cost of Service fees, which vary between the two channels.

- Several federal taxes and the Harmonized Sales Tax also apply to beer sales.

Our approach

We approached our review of the Beer Store as an adjunct to our work on the LCBO. Our principal focus was to assess whether the Beer Framework Agreement confers a material financial benefit on the owner brewers. Our analysis used publicly available information as well as information from the LCBO on its own beer retailing operations.

Our observations

TBS operates an efficient and relatively low-cost retail system. We developed an indicative assessment of costs per litre of beer between LCBO and TBS. Based on our consultant’s analysis, we estimate that TBS's costs are significantly lower than those of the LCBO.

A major contributing factor to this discrepancy is the cost of labour. As previously indicated, TBS wage rates for both permanent and casual employees appear to be meaningfully lower than those at the LCBO. Further, the LCBO has a very different business model than the Beer Store, one that is more consumer-friendly and requires more staff in each store. There is also a significant difference in non-store selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses between the Beer Store and the LCBO, largely as a result of their structure and organization.

The LCBO's Cost of Service charges for beer are too low. The LCBO's in-store Cost of Service charge has not been updated since 1989. Since that time, consumer prices have increased by 64%. As a result, the LCBO's Cost of Service charges may not be high enough to cover the business’s fully-allocated costs.

TBS and LCBO networks overlap closely. Not only are 86% of people in Ontario within a five-minute drive from a retail beer outlet, but almost 90% of TBS locations are within two kilometres of an LCBO and just over 60% are within one kilometre.

The current system could work better for consumers. Only the Beer Store is allowed to sell beer in cases of 12 or 24. This limits accessibility for consumers, many of whom prefer the LCBO's retailing experience, while preventing them from benefitting from the price breaks associated with larger pack sizes.

Canada is a very profitable market for brewers. Examination of publicly-available information for the owner brewers indicates that operating margins in Canada are materially higher than in other markets. This results from the operating environment in Canada which features:

- minimum price floors, and

- efficient distribution networks; and in certain markets

- control over distribution, and

- the ability to set the retail price for beer.

The TBS structure has the potential to generate material advantages for the three owners. Although the Beer Store operates on a break-even basis, we believe that TBS owners benefit from their ownership of the network. We believe there are a number of ways in which this may occur:

- Service charges. Non-owner brewers pay fixed service fees to sell their products in TBS. TBS owners pay an amount that varies from year-to-year, depending on actual TBS costs. As a result, any incremental service charges paid by non-owners directly benefit the three owners. This creates a risk that the costs of the system are not borne equitably by producers.

- Incremental owner market share. It is in the three owner brewers' interest to create programs and structures to increase their own market share through the Beer Store. TBS owner brands account for roughly 74% of sales in the LCBO, while we estimate that their share of beer sales in the Beer Store is over 80%.

The Ontario system benefits both owner and non-owner brewers. Although owner brewers benefit disproportionately from their ownership of the Beer Store, significant elements of the province’s beer market benefit all brewers. These include:

- Packaging. Under the Beer Framework Agreement, the Beer Store has the exclusive right to sell 12- and 24-pack formats of beer in Ontario in communities with a TBS location. This drives sales to TBS stores, further improving the network efficiency.

- Integrated distribution system. Canada is a highly profitable market for brewers. This is particularly true in Ontario. Rather than having to compensate the high number of distinct retailers and wholesalers, as in Quebec, brewers in Ontario use a fully-integrated and highly efficient system with significantly fewer points of access, reducing costs of reaching the end consumer.

- Licensees. Brewers may charge different prices to licensees than to retail consumers. As a result, many brewers charge materially higher prices to licensees than to retail customers.

- The Beer Store network. Small brewers benefit from the structure and set-up of the distribution network, given TBS's open-listing policy. Moreover, the cost-of- service fee at the Beer Store is lower than at the LCBO, improving margins for small and large brewers alike.

We believe that the relationship between the provincial government and the Beer Store should be revised to ensure that Ontario taxpayers receive their fair share of the profits from the Beer Store. Consumers should not see an increase in prices as a result of this change. The Beer Store should be required to provide greater transparency, to ensure that costs are allocated equitably among suppliers, and to treat both owners and non- owners fairly, including with respect to display of their products. The LCBO should be enabled to sell 12-packs and should increase its Cost of Service charge on beer.

The Council would like to explore with craft brewers the possibility of opening a limited number of stores featuring craft beer from around the world.

Winery retail stores (WRS)

Background

Total wine sales in Ontario amount to about $2 billion, approximately $700 million of which represents Ontario wine. Wine produced in Ontario comprises two categories of products:

- Ontario Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA), a designation which signifies that they are made from 100% Ontario-grown grapes; and

- International Canadian Blends (ICB), a blend of Ontario and imported wine that must have a minimum of 25% Ontario wine in each bottle.

ICB wines accounted for 75% of total Ontario wine sales by volume and 60% of total Ontario wine sales by value in 2014.

Wine is sold through two primary channels — the LCBO and a network of Winery Retail Stores (WRS) located both on-site at many wineries and, in the case of a few wineries, off-site as well. The WRS network also includes sales through farmers' markets, the internet, and wine clubs, and accounted for just over $250 million of the Ontario wine sold in the province in 2013–14.

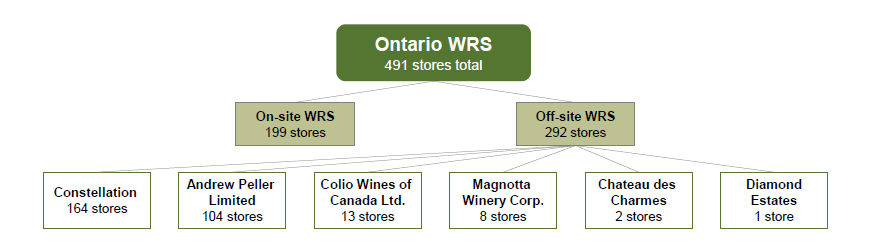

There are 491 stores in the WRS network — 199 on-site and 292 off-site. The number of on-site stores is based on the number of wineries and can change over time, while the number of off-site stores is fixed. Most off-site WRS are in a store-within-a-store format in grocery stores with Loblaws having the greatest number — 120 WRS stores.

The following chart depicts the ownership of Ontario WRS.

The capped network of 292 off-site WRS was allowed to continue operating under grandfather clauses in international trade agreements. These stores are only allowed to sell wine that is produced by the owner, and no new off-site winery retail stores can be added. There is no public disclosure provided for activity in these channels.

Over time, the vast majority of the WRS network has been consolidated under two large, publicly-traded entities — Constellation Brands Inc. and Andrew Peller Ltd.

- Constellation, based in the US, is the leading producer of premium wine in the world with almost $5 billion in annual revenue. In Canada, Constellation sells wines across all categories and price points.