Assessing the potential for ground water contamination on your farm

Learn about a risk assessment procedure to select best management practices to reduce groundwater contamination. This technical information is for Ontario producers.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published November 2024

Introduction

Safe drinking water is essential for the health and livelihood of all residents. For rural Ontarians, drinking water is usually obtained from groundwater sources, and every effort should be made to protect these sources from contamination. In agricultural settings, potential contaminants include pesticides, milking centre washwater, manure and silage leachate. Each can pose a threat to groundwater quality if not properly managed.

Reducing the risk of groundwater contamination from your property takes careful planning. A first step is to identify potential contamination sources on your property and assess the risk they pose to groundwater. The potential for groundwater contamination once a contaminant enters the soil varies from farm to farm and depends on many factors.

This fact sheet discusses the key factors affecting contaminant movement through the ground and into the groundwater. It provides a simple risk assessment procedure so you can more effectively select best management practices and plan for and take corrective actions.

Groundwater contamination

The quality of groundwater is degraded when water carries contaminants downward through the soil to the groundwater. Once a groundwater aquifer is contaminated, all water wells drawing water from that aquifer are at risk of being polluted. A contaminated water well can result in health problems and a costly clean-up process.

Factors affecting the movement of contaminants to the groundwater

The potential for groundwater contamination and subsequent water well pollution depends on many factors. Three key factors are the focus of this fact sheet:

- soil texture

- depth to bedrock

- depth to groundwater

Soil texture

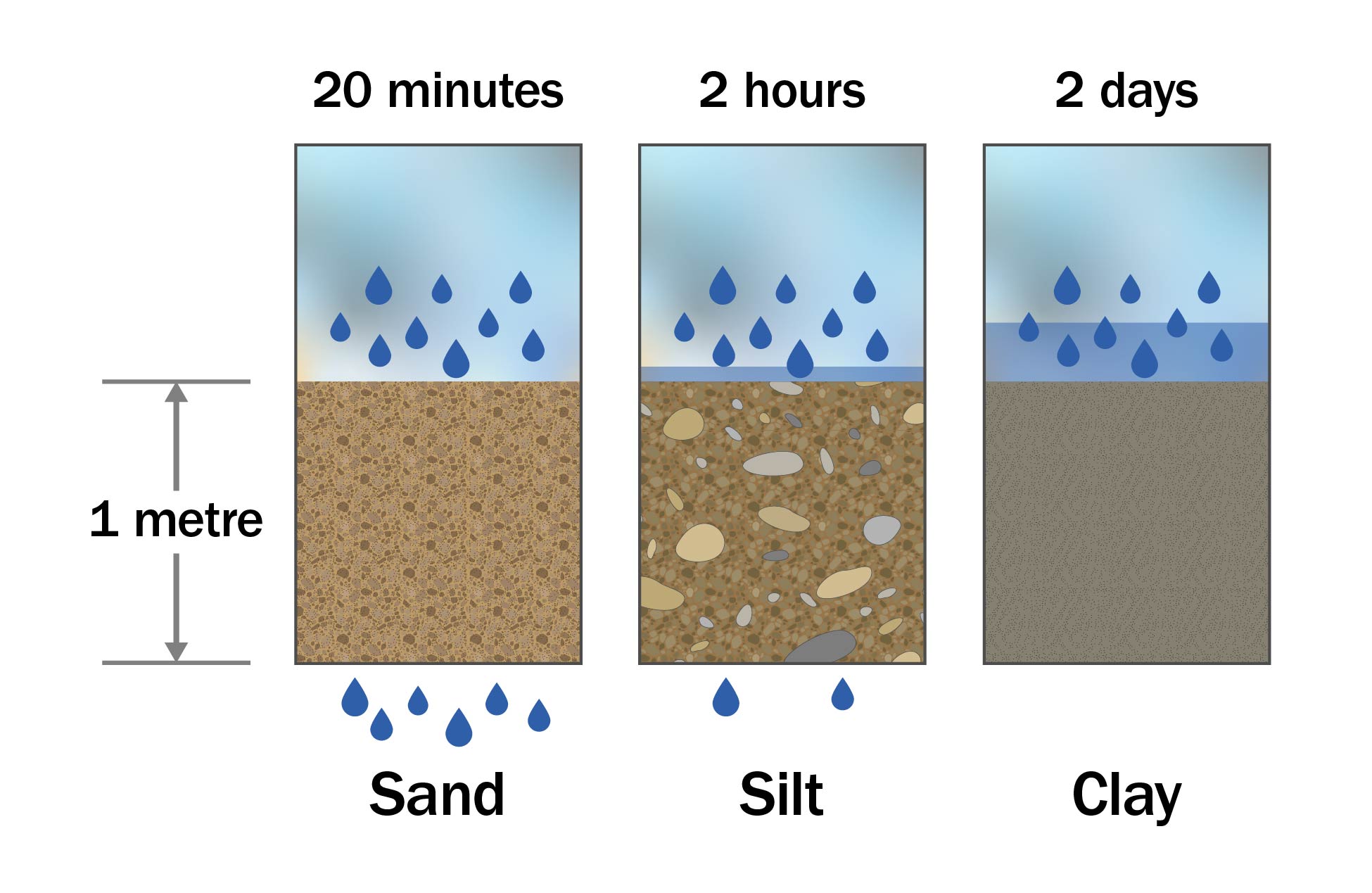

The texture of the soil is a dominant determining factor in measuring the ease and speed with which water and contaminants move through the soil to groundwater (Figure 1). Coarse-textured soils such as sands have large pore spaces between the soil particles, allowing water to quickly percolate downward to the groundwater. When water moves quickly through the soil, there is minimal time for filtration and/or natural treatment of the water to take place. Conversely, in fine-textured soils such as clays, the movement of water and contaminants through the soil is very slow. These fine-textured soils act as a natural filter, allowing bacteria and other soil organisms to break down contaminants before they reach the groundwater. Fine-textured soils provide much better natural protection for groundwater than coarse-grained soils. Note that if surface clays dry, they can shrink and crack, leading to rapid movement of surface water through the resulting cracked openings to lower regions of the soil profile.

Depth to bedrock

Open fractures in the bedrock allow for a rapid movement of water and contaminants to the groundwater. If the depth of soil over the bedrock is shallow, there is little opportunity for the soil or soil organisms to filter the water as it moves through this shallow layer of soil. Once the water and contaminants reach the bedrock, movement to the groundwater is often very swift.

Depth to groundwater

The filtering of contaminated water primarily takes place in soil above the water table (the unsaturated zone of soil). A high water table results in a shorter travel time for water and contaminants to move through this unsaturated soil before reaching the groundwater, therefore, there is little opportunity for the filtering of water to occur. Water table depths can fluctuate dramatically, depending on the season of the year. The water table is usually highest in the spring or late fall.

Assessing the potential for groundwater contamination

On the farm, there are many potential sources of contaminants. They are usually classified as point sources where potential contaminants are concentrated or stored in one spot (such as manure piles, fuel storages) or non-point sources where the potential contaminants are spread out over a greater area (such as pesticide or fertilizer applied to fields). Regardless of the source, some farms or areas of farms may be much more susceptible to groundwater contamination if contaminants enter the ground. Table 1 estimates the potential for groundwater contamination. This assessment method is only intended as a guide and considers only the three factors of soil texture, bedrock depth and depth to groundwater. The primary consideration is the relative speed with which contaminants move through the soil. It is assumed the soil profile is uniform and not layered.

To determine a site’s potential for groundwater contamination, find the soil hydrologic class (SHC) assigned to your soil in the first column of Table 1 and move horizontally to the appropriate “Depth to groundwater” column. If no SHC has been assigned to your soil, then consider the texture or the hydrologic soils group (HSG) of your soil, as an alternate approach for finding your soil in column 1.

The following guidelines may be helpful when using Table 1:

- If bedrock or groundwater is within 0.9 m (3 ft) of the soil surface, or the soil type is muck/organic, the potential for groundwater contamination will always be “high.”

- To determine the SHC for the soil at the site, either:

- Refer to the Environmental Farm Plan, County Soil Summary Sheet or the program’s Soil Calculator, available through the Environmental Farm Plan program representative (Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association) assigned to your area.

- Use the Hydrologic Soil Class using the HSG layer in AgMaps to identify the HSG site and then convert to the corresponding SHC (Table 1).

- Consult Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness (OMAFA) Publication 29: Drainage Guide for Ontario, to determine the HSG assigned to your soil and relate that to the SHC (Table 1).

- Have a field evaluation of your soils conducted to determine the characteristics of water movement through your soil.

- The following methods may be used to determine groundwater depth (water table):

- Digging a post hole in early spring often reveals the depth to the water table where a high water table exists.

- The depth to the water level in a dug well is a good indicator but do not use the static water levels in drilled wells. Static water levels in drilled wells usually do not reflect the near surface water table location.

- If the water table cannot be found, use the 0.9–4.5 m (3–15 ft) “Depth to groundwater” column in Table 1.

Legend: Ratings of the potential for groundwater to become contaminated if there is a spill or leak of a contaminant:

- 1 = high

- 2 = moderate

- 3 = low

- 4 = very low

| Soil hydrologic class | Typical soil texture | Corresponding HSG | Depth to groundwater: less than 0.9 m (3 ft) | Depth to groundwater: 0.9–4.5 m (3–15 ft) | Depth to groundwater: 4.6–13.5 m (16–45 ft) | Depth to groundwater: greater than 13.5 m (45 ft) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedrock (within 0.9 m (3 ft)) | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Muck/organic | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Rapid | sand | A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Moderate | loam | B | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Slow | clay loam | C | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Very slow | clay | D | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

To get a more accurate assessment of the potential for groundwater contamination on your farm, look for varying hydrogeological conditions such as changes in soil texture, bedrock types and depth to groundwater, and carry out enough site inspections to account for these variances. Always assess the farmstead area around the farm buildings separately from the field areas.

The potential for contamination of a specific water well on your farm can be further assessed by considering the separation distance from the potential contaminant source to the water well. The greater the separation distance, the less chance the contaminant will affect the well, either through groundwater flow or by surface flow. Using Table 2, determine the minimum recommended separation distances between potential contaminant sources and water wells by using your sites (from Table 1) and your well type.

In Table 2, potential contaminant sources may include point sources around the farmstead such as manure storages, fuel storages, septic systems, pesticides storages, etc.

| Potential for groundwater contamination (from Table 1) | Separation distance between potential contaminant source and water wells (drilled wells) | Separation distance between potential contaminant source and water wells (dug or bored wells) |

|---|---|---|

| High | Greater than 90 m (300 ft) | Greater than 90 m (300 ft) |

| Moderate | 24–90 m (76–300 ft) | 47–90 m (151–300 ft) |

| Low | 15–23 m (50–75 ft) | 30–46 m (100–150 ft) |

| Very low | At least 15 m (50 ft) | At least 30 m (100 ft) |

Reproduced from the Ontario Environmental Farm Plan.

Nutrient Management Act (NMA), 2002

New and expanding facilities on farms in Ontario that are phased-in under the Nutrient Management Act, 2002, must meet the minimum setback distance requirements of O. Reg. 267/03, as amended. AgriSuite is a tool that can assist in you in identifying minimum setback distances between wells and land activities.

Measures to counteract a high potential for groundwater contamination

A high or moderate groundwater contamination potential is an indication of the speed that contaminants move downward to the water table if a spill or leak occurred. The result could be a rapidly contaminated aquifer and a potentially polluted water well on your property and your neighbours’. If this high risk exists on your property, take special care to prevent leaks or spills of contaminants. Conduct regular inspection, maintenance and water testing of the water well. Containment of manure, livestock yard runoff and milking centre washwater is necessary to reduce leaching down to groundwater. As for field areas, apply manure and fertilizer at the proper rate to meet the crop’s requirements and at the proper time of year to maximize the use of the nutrients, otherwise, valuable nutrients could percolate down to groundwater.

Resources

Best management practices (BMPs):

OMAFA fact sheets:

- Understanding groundwater

- Managing the quantity of groundwater supplies

- Protecting the quality of groundwater supplies

- Highly vulnerable water sources

- Private rural water supplies

- Testing and treating private water wells

Disclaimer

The information in this document is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon to determine legal obligations. To determine your legal obligations, consult the relevant law. If legal advice is required, consult a lawyer. In the event of a conflict between the information in this fact sheet and any applicable law, the law prevails.

Author credits

This fact sheet was updated by Amber Langmuir, P. Eng., engineering specialist, water management, OMAFA, and Kevin McKague, P. Eng., engineering specialist, water quality, OMAFA.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph The minimum separation distance required between the type of water well and a potential source of contamination to be consistent with water well construction regulations under the Ontario Water Resources Act, 1990 (Reg. 903).