Manure management for farms producing more manure than their crops need

Learn how to determine landbase needs to manage manure and options if enough landbase is not available. This technical information is for Ontario farmers.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published November 2021

Introduction

Manure is an excellent source of plant nutrients, however, applying too much of it to an area of land can increase the risk of environmental concerns. This fact sheet outlines how to determine landbase needs and discusses options for farms to manage manure if enough landbase is not available.

Determining landbase needs

There are a number of factors to consider in order to determine the landbase capacity of your Farm Unit to safely receive manure.

Under the 2012 Nutrient Management Protocol for O. Reg. 267/03, a Farm Unit is the land and associated facilities of an agricultural operation.

The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) cloud-based agricultural planning tools suite, AgriSuite, contains decision support tools to help farmers determine values for each of the following factors:

Factor 1: Nutrient value of manure to be applied

The nutrient value of manure varies greatly between different types of livestock (Table 1). The best way to determine the nutrient value of your manure is to have it analyzed by an accredited laboratory for nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and dry matter content. For a representative liquid manure sample, take liquid manure samples from an agitated tank to obtain an accurate estimate of nutrients. For a representative solid manure sample, take samples from several locations of a manure pile. Average manure nutrient concentrations for a range of livestock types are found in AgriSuite.

| Type of livestock | # Animals per NU |

|---|---|

| Large frame dairy cow | 0.7 |

| Beef feeders | 3 |

| Swine — finishing pigs | 6 |

| Lamb feeders | 20 |

| Chickens — layer pullets | 500 |

Factor 2: Planned crop rotation

The nutrient requirements of crops vary from one crop to another. What are the nutrient requirements of your current crop rotation? Can your manure application meet these requirements?

Factor 3: Current soil nutrient levels, soil type and topography of the landbase

If soil nutrient levels are already high, nutrient additions from manure could be limited. The best way to determine the nutrient levels in your soil is to submit a soil sample for analysis. Soil type and topography can also limit the landbase capacity for manure due to the higher risk of contaminated runoff from soil with low soil infiltration and steep slopes.

Factor 4: Proximity to watercourses or other environmentally sensitive areas

To reduce the risk of surface or well water contamination, setbacks for manure application are used. Consider these setbacks when calculating how much land remains for manure application.

Setbacks in Ontario

- 100 m (328 ft) from municipal wells

- 15 m (50 ft) from drilled wells or 30 m (100 ft) from any other well

- 3–60 m (10–200 ft) from the bank of surface water. This setback depends on a number of factors such as the incorporation method used, the slope near the watercourse and the P Index value (see OMAFRA fact sheet, Determining the Phosphorus Index for a Field).

Part VI in the Regulation specifies required setbacks for regulated farm units. The setbacks resulting from the P Index are not regulated but are still a recommended practice.

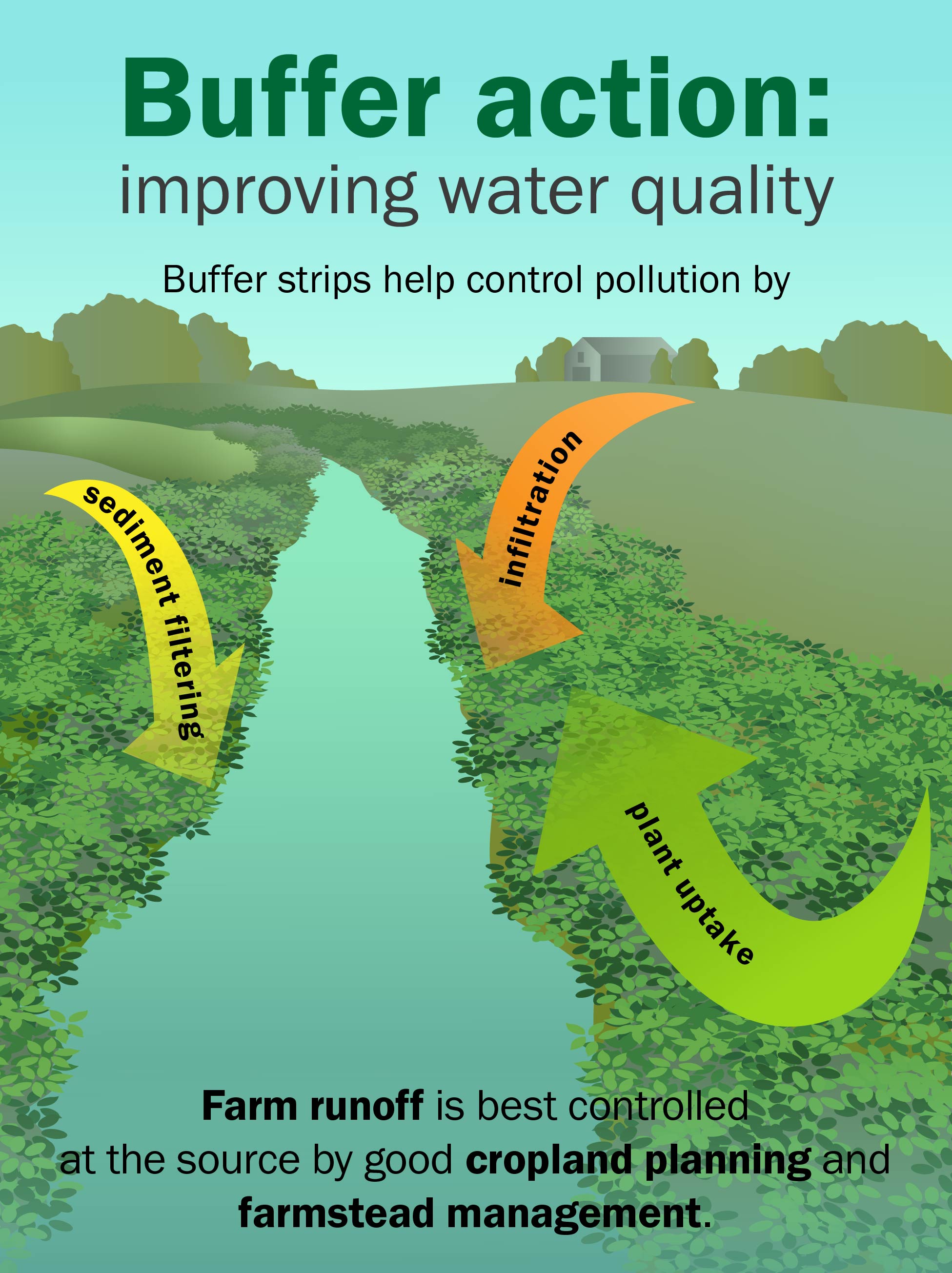

In addition, a 3 m (10-ft) buffer is required along all watercourses in fields where nutrients are applied and a nutrient management plan is required under the Regulation (except on organic soils) (Figure 1).

Options for farms that produce more manure than their landbase can handle

If you have more manure nutrients than your landbase can handle, consider the following options:

- increase the size of the landbase

- reduce the amount of manure nutrients to handle

- apply more manure to the same landbase

- move manure off-site

- adopt innovative treatments of manure

Option 1. Increase the size of the landbase in the farm unit

There is enough cropland in Ontario to handle all the nutrients from manure in the foreseeable future. The challenge is in obtaining a localized landbase for the farm’s manure, since transporting manure to remote sites can be costly (see end of this section for more on landbase accessibility).

There are five approaches to increase the size of the landbase in your Farm Unit.

Purchase more land on the same property deed as the livestock facility

Incorporating an additional landbase onto the same deed gives greater assurance that a proper landbase remains with the barns that produce the manure. This process is accomplished by purchasing an adjoining landbase. After purchase by the same owner, the properties are then joined on the same deed.

As livestock operations become larger, obtaining enough adjoining properties will be difficult. It is expected that many operations will gradually expand their landbase as properties surrounding the livestock operation become available.

Purchase more land on a different deed

Owned land on a different deed gives the operation full control of use of the landbase. However, the additional property could be sold in the future, possibly leaving the livestock facility without an adequate landbase.

This land should be located close to the livestock facility to lower the cost of manure handling. Consider the accessibility of this land base for spreaders or direct flow manure application systems (for example drag hose systems) (Figure 2).

Note: The use of high trajectory irrigation guns as a direct flow manure application method is prohibited by the NMA regulation when the manure being applied exceeds 1% dry matter.

Rent land on a long-term lease

Tillable land rented by the owner of the livestock operation on a long-term lease is generally preferred over a manure application agreement. The renter has control of the timing and scheduling of crops to facilitate the application of manure. This is especially important if the livestock operation has limited manure storage capacity.

Note: For NMA regulation purposes, rented or leased land is treated the same as owned land (that is it is under control by the operator).

Use a manure application agreement

A manure application agreement is another way to handle manure without land purchase. Though the land listed in an application agreement would not become a registered part of a farmer’s deeded property, the farmer would list the land on his Farm Unit Declaration Form when completing a Nutrient Management Strategy (NMS).

Note: A manure application agreement is not a required agreement under the NMA regulation, but it is an option for the farmer.

The longevity of the agreement can range from 1–5 years or more. The landowner is more likely to renew their agreement in the long term if they see the land receives benefit from the manure. If the manure is unevenly applied or if damage occurs during application, the landowner may not gain any benefit and consequently may refuse to continue with the agreement. Proper nutrient testing, development of an NMP and uniform, non-compacting application are keys to maintaining mutual benefit.

Rent land on a short-term lease

Consider a short-term lease if the livestock operation is in an area where land is regularly available for rent. Then, if one lease is lost, another lease can be picked up. If land is rarely available for rent, expansion based on a short-term lease should not be considered.

Note: For a regulated farm unit, a manure application agreement or rental agreement can be for as little as 1 year. It is expected that the operator will continue to renew this agreement within the strategy. If the agreement is not renewed, it is recommended the operator prepare a new Nutrient Management Strategy (NMS) if the loss of land means the amount of manure being generated exceeds the amount that the NMS can accommodate.

Landbase accessibility for manure application

In all five approaches, the accessibility of manure-application equipment to the properties must be considered due to the large volumes of manure that is to be handled. For example, at a typical rate of 47 m3 of manure/ha (5,000 gallons/acre), 2,500 tonnes of manure would be applied to a 40.5-ha (100-acre) farm (approximately 6 times the weight of dry corn you would harvest from the same acreage) (Figure 3).

Transporting 2,500 tonnes of liquid manure via a tractor trailer to a remote site (over 3 km (2 miles)) could become expensive. The actual transportation costs are affected by a number of factors including the amount of manure to be transported, distance to the remote site, access to transportation equipment or road configuration (for example hills, drive through towns/hamlets, crossing major highways, etc.). For example, applying manure to a remote site rather than a local one could add an additional cost of 1 cent per gallon of applied manure because of added transportation costs. At an application rate of 47 m3/ha (5,000 gal/acre), this would mean an additional cost of $124/ha ($50/acre).

If using manure spreaders, consider road travel and crossings necessary to access a remote field. Turns on busy highways are very dangerous since the large tanker often reduces or blocks visibility. Repeated turns by a loaded multi-axle tanker on hot pavement can cause extensive damage to the road. Safety concerns and extensive equipment damage could also occur to farm equipment if the size of the manure tanker is too big for the size of the tractor pulling it.

Direct flow liquid manure uses a pipeline to move the manure to the field. In many situations, at least one road, stream or private property crossing will be involved to reach a field. Permission must be obtained for any crossing or road access. For a livestock farm, consider the installation of a permanent underground pipeline to remote fields. Although more expensive initially, it allows for quick, long-term access.

Option 2. Reduce the amount of manure nutrients to handle

Reducing nutrients in the manure will result in a decrease in the amount of land required to spread manure from the farmstead (unless liquid loading is the limiting factor). There are three approaches:

Improve efficiency of nutrient conversion from feed to product

Processes that improve the productivity of a livestock operation (such as genetic improvements or feed ration balancing) will improve nutrient conversion. However, in some cases there is a trade-off between conversion efficiency and productivity. An operator must balance all factors in making a decision.

Specialized feed additives are designed to make certain nutrients in feed more usable to the animal. These products should improve nutrient conversion and reduce nutrient levels in manure. For example, the additive phytase has been found to reduce phosphorus in swine manure by 25%–50%.

Feeding animals a ration that is finely tuned to their nutritional needs can also reduce animal manure nutrient output and reduce the amount of feed spillage. Feed spillage is reduced by using high-quality feeds, spill-resistant feeders, good management and recycling of refused feed to other animals.

Decrease livestock production

If you reduce the number of animals on the farm, you will decrease manure production. For livestock farms, this approach is not always practical.

Remove nutrients from manure

Some treatments of manure will reduce the amount of a particular nutrient to handle. For example, during a composting process, if not done correctly, nitrogen may be lost to the air in a form of ammonia. This “lost” nitrogen can cause odour concerns and result in loss of a nitrogen source for crop fertilizer.

Option 3. Apply more manure to the same landbase

Increasing the application rate of manure without causing environmental problems or crop yield reductions is another approach to deal with excessive manure nutrients. Listed are five approaches to increase manure application rates.

Reduce commercial fertilizer use

By reducing commercial fertilizer applications, you may be able to apply a higher rate of manure to a field. Develop a Nutrient Management Plan to properly match the nutrients in both the manure and fertilizer with the crop nutrient requirements. This plan should include manure and soil nutrient tests. OMAFRA’s AgriSuite allows you to match these requirements and test various “what if” scenarios.

Note: A Nutrient Management Plan must be developed if the manure is to be applied on a regulated farm unit that generates 300 nutrient units or more, or if any part of the farm unit is less than 100 m (328 ft) from a municipal well.

When using manure as a major source of nutrients, it is important to apply the manure evenly and at the correct rates using properly calibrated application equipment. New technology is becoming available to improve calibration and provide uniform application of manure (Figure 4).

Reduce use of organic nutrient sources

Other nutrient sources such as ploughed-down red clover or sewage sludge applications can provide a significant addition of nitrogen to a field. In most cases, the operation will benefit. However, if the full landbase is required to use nitrogen in the manure, then reconsider the use of these organic nutrient sources.

Increase crop uptake of nutrients

Increasing crop nutrient requirements will proportionally increase the amount of nutrients that can be applied to the field. Examples of increasing crop uptake are:

- change to a crop or crop rotation that removes more nutrients from fields (Table 2)

- produce higher yielding crops

- switch to some legume-based crops such as alfalfa, which use high levels of all nutrients (an alfalfa crop will use soil-based nitrogen if available rather than producing its own)

Use AgriSuite to estimate multiple “what if” scenarios.

| Crop | Yield | Nutrient removal N | Nutrient removal P | Nutrient removal K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn silage | 51 tonnes/ha (23 tons/acre) | 229 kg/ha (204 lb/acre) | 96 kg/ha (86 lb/acre) | 198 kg/ha (177 lb/acre) |

| Alfalfa hay | 12 tonnes/ha (5 tons/acre) | 309 kg/ha (276 lb/acre) | 63 kg/ha (56 lb/acre) | 294 kg/ha (263 lb/acre) |

| Soybeans | 3 tonnes/ha (45 bu/acre) | 193 kg/ha (172 lb/acre) | 42 kg/ha (38 lb/acre) | 70 kg/ha (63 lb/acre) |

| Grain corn | 11 tonnes/ha (175 bu/acre) | 162 kg/ha (145 lb/acre) | 82 kg/ha (73 lb/acre) | 57 kg/ha (51 lb/acre) |

| Winter wheat | 5.7 tonnes/ha (84 bu/acre) | 113 kg/ha (101 lb/acre) | 55 kg/ha (49 lb/acre) | 34 kg/ha (30 lb/acre) |

Source: AgriSuite 2021.

Allow build-up of nutrients in the soil

Phosphate and potassium will build up in the soil profile if applied exceeding the crop’s needs. If initial soil levels are low, then some increase is preferable, provided that separation distances from surface water are maintained. However, there will be a limit on how long a build-up can continue before environmental problems or crop growth restrictions occur. A nutrient management plan, completed using AgriSuite, will identify situations where P should not be applied over crop removal or not be applied at all.

Note: If P levels get too high, the phosphorous limit in the regulation may restrict the addition of P beyond crop-removal levels, or in some cases, restrict the addition of P nutrients altogether.

Since a livestock operation is a long-term venture, do not base most landbase calculations on significant nutrient build-ups in the soil. One exception is when a remote landbase is used for a limited number of years.

Improve the absorbing ability of the soil

The ability of soil to absorb manure may be limited by wet, compacted soils and/or steep slopes. The absorbing ability of the soil can be improved by pre‑cultivation or by improving the soil structure.

Alternatively, higher rates of manure application may be achieved by completing multiple application passes with each pass at a very low rate.

Contamination of drainage tile water via cracks to the soil surface is another concern. Use of reduced rates, tillage prior to manure application or monitoring of tiles may be necessary in fields prone to this problem.

Option 4. Move manure off-site

In some cases, transfer of manure to an off-site location may be preferable.

Manure broker agreements

In some areas of Ontario, a manure broker (also called a manure removal contractor) will take the manure from the barn, store it and transfer it to another client. This approach is frequently used for handling solid manure (such as broiler manure) where there is a substantial demand for the manure as a source of organic matter for growing crops.

Note: When a broker is used as a part of an NMS, include the appropriate broker agreements. These agreements demonstrate an understanding between the farmer and the broker that once the broker takes the manure, it will be managed responsibly under an NMS/P.

Manure transfer agreement

A manure transfer agreement is used to transfer manure to another farm that is not part of the same farm unit.

Note: Two types of agreements are used. If the receiving farm is another regulated farm unit, a Nutrient Transfer Agreement is completed. This transferred manure must be included in the receiving farm’s NMS. If the receiving farm is not a regulated farm unit, information must be included in the generator’s NMS to indicate the receiving farm’s area, type and livestock information.

Option 5. Adopt innovative treatments of manure

The main goal of manure treatment is to produce a product that is easier to handle and less objectionable to users and their neighbours (therefore increasing or maintaining the landbase available to spread). The following are three ways to treat manure:

Manure separation

Separation produces a “solid” component out of liquid manure. This “solid” material is easy to transport and in demand by potential customers. The remaining liquid component is typically spread at livestock operation. In some cases, separation can be completed by just continuously draining the liquids from the manure. More complex systems such as a screw separator can be used to extrude a solid material from liquid manure (Figure 5). It is expected that 20% of the total nutrients from a free-stall barn can be “solidified” this way.

Another approach to producing a solid material is to change the manure handling and storage system to produce a solid form of manure. An example of this is in layer barns where belt manure-handling systems are used along with water conservation to produce a solid form of manure. Research projects indicate that the same technology can be used in hog-finishing barns where a sloped belt under the slats immediately separates the solids from the liquids.

Manure composting

Composting solid manure can reduce the total volume by 30%–50% and decrease the odour level. This results in less volume of product to be handled and a possible off-farm use by horticultural or residential users.

Increase the nutrient concentration in liquid manure

Reducing the water content in liquid manure will concentrate the nutrients in manure, making it easier to justify the cost of transferring the nutrients to remote fields. Practices such as keeping roof water out of the storage, covering the storage or installing water drinkers with less water loss can often reduce the volume of waste to be handled. For example, adding wet/dry feeders to swine finishing barns can reduce waste to be handled by at least 20%.

Anaerobic digesters

A digester treats manure in an oxygen-free environment. Biogas is produced as part of the process that is used to heat the digester with surplus available to produce renewable heat and electrical energy. While it does not reduce the volume or nutrient content, it causes a substantial decrease in odour and pathogen levels in the effluent.

Conclusion

There are many options to reduce landbase requirements for manure. Carry out proper planning before the time of construction or expansion of a livestock facility to ensure that adequate landbase is available for manure application. On farms where the landbase needs are only just met, the farmer should have a comprehensive contingency plan to safely handle any increases in manure volume or decreases in available landbase.

Resources

OMAFRA fact sheet, Manure agreements with brokers and neighbours. See Appendix 1 in the PDF for a sample of a manure application agreement.

Nutrient Management Act, 1990 — Regulations and Protocols:

- Calculating nutrient units is found in 2021 Nutrient Management Protocol for O. Reg. 267/03

- Maximum liquid manure application rates is found in Part VI in the Regulation

- Setbacks from water courses is found in Part VI in the Regulation

- Ban on use of high trajectory irrigation guns is found in Part VI in the Regulation

- Nutrient management plans are found in Part III and 2021 Nutrient Management Protocol for O. Reg. 267/03

- Phosphorus index and limits are found in Part IX and in AgriSuite

Nutrient management disclaimer

The information in this fact sheet is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon to determine legal obligations. To determine your legal obligations, consult the relevant law. If legal advice is required, consult a lawyer. In the event of a conflict between the information in this fact sheet and any applicable law, the law prevails.

This fact sheet was updated by Richard Brunke, P. Eng., nutrient management engineer, OMAFRA.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph An NU is equal to the amount of manure needed to give the fertilizer replacement value of the lower of 43 kg of N or 55 kg of P. For example, it takes the manure from 3 beef feeders to get the equivalent of 1 NU.