2024–2025 Chief Drinking Water Inspector annual report

Learn about the performance of our regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, drinking water test results, inspection and enforcement activities and programs.

Message from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector

Each year, we publish the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Report to give a clear picture of how Ontario’s drinking water systems perform. It is part of our commitment to transparency, accountability, and continuous improvement. I am proud to report that our province continues to uphold some of the most rigorous water safety standards in the world, grounded in Justice O’Connor’s recommendations following the Walkerton Inquiry. These principles—particularly the multi-barrier approach and the importance of central oversight—remain vital to our collective mission of protecting public health.

However, safeguarding drinking water requires vigilance. Climate pressures, aging infrastructure and other emerging challenges demand continued investment and leadership. As this report highlights, providing reliable, clean water for Ontarians is a shared responsibility—and one we must continue to advance with transparency, integrity, and innovation.

I want to thank the thousands of dedicated professionals—water system operators, regulators, engineers, and public health experts—whose commitment helps keep our drinking water safe, day in and day out.

Explore the full report to learn more about how Ontario’s drinking water systems are performing, and the work being done to maintain the safety of drinking water in the province.

Steven Carrasco

Chief Drinking Water Inspector

Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

Message from the Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ontario is blessed with an abundance of freshwater. It is one of our province’s greatest natural assets, shaping our landscapes, supporting our ecosystems, and nourishing our communities. With this abundance comes a shared responsibility to protect it. Protecting the safety of our drinking water is not simply a matter of public health, but a meaningful act of community.

Drinking water touches every part of our lives. It’s in the meals we prepare, the care we receive, and the places where we gather. The Small Drinking Water System Program helps ensure that people drinking water from these systems, whether in a local restaurant, a rural clinic, or a seasonal campground, can have increased confidence in the water they drink. This program helps keep water safe through tailored oversight and collaboration between public health inspectors and system operators.

The results presented in the 2024-2025 Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report reflect the strength of the Small Drinking Water System Program and the dedication of those who support it. Over 98% of nearly 100,000 drinking water test results met Ontario’s water quality standards. More than 92% of these systems are now categorized as low or moderate risk, and the proportion of high-risk systems has continued to decline. Most importantly, adverse water quality incidents at these systems have decreased significantly over time, and no illnesses have been reported.

These outcomes speak to the effectiveness of the program and the care taken by the operators and public health units involved to respond quickly and effectively when issues arise. They also illustrate what can be accomplished with strong partnerships and a commitment to continuous improvement.

I want to thank everyone involved in the Small Drinking Water System Program for their ongoing efforts to protect one of Ontario’s most vital resources. Their work helps safeguard the water on which so many Ontarians depend.

Dr. Kieran Moore

Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ministry of Health

2024-2025 at-a-glance

Statistics

In 2024-2025:

- 99.9% of the more than 500,000 drinking water test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s health-based Drinking Water Quality Standards (“standards”)

- 99.7% of more than 40,000 results from non-municipal year-round residential systems met the standards

- 99.7% of almost 60,000 results from systems serving designated facilities (such as child care centres and long-term care homes) met the standards

- 98.1% of nearly 100,000 test results from small drinking water systems met the standards

- 97.5% of more than 21,000 test results met the standard for lead in drinking water at schools and child care centres

- when looking at flushed samples only, this number increased to 98.7%

- 99% of licensed laboratories and municipal drinking water systems received a compliance rating greater than 90%

- 8,018 operators were certified to run drinking water systems and 1,788 drinking water operator certificates were renewed

- • Approximately $6.8 million was disbursed to transfer payment recipients from the approximately $20 million in funding that has been committed for source water protection over 3 years (2024-2027)

Update on ministry actions to protect drinking water

Drinking water benchmark list

The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks is developing an online version of a Drinking Water Benchmarks List. The list will provide a central repository of the existing drinking water quality standards, aesthetic objectives, and operational guidelines which are considered in the production of high-quality drinking water in Ontario.

The list is designed to be a searchable source of information related to drinking water quality parameters. It will be used by drinking water system operators, health unit staff, private well owners, and members of the general public with an interest in drinking water quality and contaminants. In addition, the list can be updated as new standards, aesthetic objectives and operational guidelines are developed, to help maintain it as a current source of valuable information.

The Drinking Water Quality Management Standard (DWQMS) sets requirements for comprehensive management systems that support the delivery of high quality drinking water from Ontario’s municipal drinking water systems. In 2024-25 the ministry updated the DWQMS to clarify existing requirements, reflect current practices in drinking water system management, and enable the auditing of processes used to summarize monitoring data. Version 3.0 of the DWQMS will be posted on the Environmental Registry of Ontario.

Read more: Updates to the drinking water quality management standard

Source water protection

In 2024-25, the ministry continued to facilitate work through transfer payment agreements with source protection authorities across the province. This year approximately $6.8 million was disbursed to recipients to support protecting drinking water sources from depletion and contamination.

Municipal drinking water systems are expanding or changing in response to population growth, and this often changes the drinking water protection zones surrounding them. As well, several source protection plans have needed to be revised to address the ministry’s updated Technical Rules released in 2021 and, for example, to re-evaluate the risks from road salt and update policies to address those risks. In the 2024-2025 fiscal year, 8 source protection plans were amended or updated to incorporate changes to drinking water systems, update science, and/or address implementation challenges.

Moving forward

Best management practices

The DWQMS requires municipalities to review and document the consideration of all applicable drinking water best practices that have been published by the ministry. These practices support the delivery of safe, high-quality drinking water, help improve how systems run, and provide information to aid in future planning for municipal systems. By publishing best management practices, the ministry is making it clearer which ones to consider, while also encouraging system owners and operators to take action and put them into use.

Read more: Drinking water system best management practices

Accelerating and improving protections for Ontario’s drinking water sources

Changes were made to the Clean Water Act, 2006 that will enable local source protection authorities to approve routine source protection plan amendments and promote certainty in the process and timelines where Minister’s approval is still required. The amendments also include changes related to policies affecting prescribed instruments, such as certain licences and permits, to enhance consistency, transparency and accountability, while maintaining strong protections and oversight for our sources of drinking water.

Drinking water protection framework

Figure 1: Drinking water protection framework

- source-to-tap focus

- strong laws and regulations

- health-based standards for drinking water

- regular and reliable testing

- swift, strong action on adverse water quality incidents

- a multi-faceted compliance improvement toolkit

- mandatory licensing, operator certification and training requirements

- partnership, transparency and public engagement

- all the components work together to protect Ontario's drinking water

Ontario’s drinking water protection framework aims to keep drinking water safe through multiple protective barriers and checks and balances. These include:

- strong legislation

- source protection plans

- stringent health-based drinking water quality standards

- highly trained and certified operators with continuing education requirements

- frequent operational checks and water monitoring

- precautionary reporting

- regular inspections of drinking water systems and licensed laboratories

- partnership, transparency, and public engagement

Ontario continues to work with our partners through this comprehensive, multi-barrier framework to protect Ontario’s drinking water from from its source onward.

The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks regulates various kinds of drinking water systems and related activities set out in the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002, including:

- Municipal residential drinking water systems that are owned by municipalities and supply drinking water to homes and businesses.

- Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems that are privately owned and supply drinking water all year to 6 or more private residences in places such as trailer parks, apartments, condominiums, and townhouse developments. This also includes drinking water systems owned by local services boards, which are volunteer organizations that are set up in rural areas where there is no municipal structure.

- Public and privately owned systems serving designated facilities that have their own source of water and provide drinking water to facilities such as children’s camps, schools, health care centres, and senior care homes.

- Licensed laboratories that perform testing of drinking water.

- Certification and training for water operators and water quality analysts in Ontario.

The ministry has a comprehensive compliance program, which includes inspecting drinking water systems and laboratories, managing drinking water related incidents such as adverse water quality incidents, and supporting the regulated community with outreach and education measures.

Children’s camp initiative

The ministry recruited, trained, and mobilized a network of summer students across the province to engage in information gathering, education, and outreach to owners and operators of children’s camps.

Students engaged in the following education and outreach activities with children’s camps:

- verified that the drinking water systems’ profile information was accurate and up to date

- provided outreach to systems about general drinking water regulatory requirements including adverse water quality incident (AWQI) reporting and record retention requirements

- provided outreach to systems about blue-green algal blooms, where applicable

- conducted a short survey to obtain feedback on current ministry guidance materials and sought suggestions for improving them or generating new materials that may be useful

The project resulted in the students contacting more than 80% of targeted children’s camps, primarily through on-site visits. Approximately 50% of the children’s camps had their drinking water systems’ profile information updated. The ministry continues to monitor compliance within this sector to find further outreach opportunities.

Feedback from the children’s camps and the students was positive overall. Camps expressed appreciation for the information provided as well as the personal interaction with students and ministry staff. Students reported positive work experience interacting with the children’s camps.

Compliance actions

Inspections of drinking water systems and laboratories are a key tool in the multi-faceted compliance monitoring within the provincial drinking water protection framework.

During an inspection of a drinking water system, the water compliance officer will collect information to evaluate compliance and make notes to record details of the inspection. The officer will typically inspect the drinking water treatment equipment, interview personnel, review records and data, and take photographs.

During an inspection of a laboratory, the laboratory inspector will tour the facility, interview personnel, review records, and trace drinking water samples from receipt to reporting test results, among other things.

All drinking water systems and laboratory owners are issued a report with the inspector’s findings including any instances of non-compliance.

When non-compliance is identified, the inspector generally works with system or laboratory owners to help bring them into compliance. For more serious instances of non-compliance, the inspector may issue an order requiring remedial actions or request an investigation by the ministry’s Environmental Investigations and Enforcement Branch.

The decision to request an investigation for non-compliant behaviour typically depends on several criteria, including:

- the potential impact of the non-compliance on the health of the users of the drinking water system

- the compliance history of the inspected system owner and/or operator

- the level of the owner’s cooperation in coming back into compliance

- what steps the owner and/or operator has taken or is taking to resolve the issue

The Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (Ontario Regulation 242/05 made under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002) also requires that the ministry take mandatory action (for example, issue an order or request an investigation into the matter) when a violation may compromise the safety of the drinking water. This is further detailed in the Compliance and Enforcement section below.

Sampling, monitoring, and reporting

Regular monitoring and sampling at drinking water systems is required so that water quality issues are quickly identified and addressed.

Further, when a prescribed drinking water sample exceeds an Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standard or there is an observation of improperly treated drinking water at a regulated drinking water system, immediate reporting is required to both the ministry’s Spills Action Centre and the local medical officer of health.

Additional reporting is also required for exceedances or observations of improper disinfection at drinking water systems that serve designated facilities.

Both the laboratory that conducted the tests in question and the drinking water system’s operating authority (or owner, if no operating authority is responsible for the system) must immediately report the issue to the ministry’s Spills Action Centre and the local medical officer of health. If an operating authority is responsible for the drinking water system, it must also immediately report the adverse test result to the owner of the system.

The summary above is general and does not cover all aspects of the reporting requirements related to drinking water sample exceedances or improper disinfection. For more details, reference should be made to the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 (in particular, section 18) and regulations made under that statute (in particular, Schedule 16 to Ontario Regulation 170/03 Drinking Water Systems).

It is important to note that the report of an adverse test or operational issue (for example, low chlorine or improper disinfection) does not necessarily mean that the drinking water is unsafe. However, it does mean that the owner and operator need to investigate what may have caused the adverse result or operational issue and take all steps necessary to resolve it. Ministry water compliance officers follow up on such reports as needed.

The ministry also follows up on lead exceedances in schools and child care centres and works with operators of those schools and child care centres, as well as with the local medical officer of health, to resolve issues. When a test result exceeds the standard for lead, facility operators must report it to the local medical officer of health, the Spills Action Centre, and the Ministry of Education. If a result from a flushed sample fails to meet the lead standard, owners and operators must take immediate action to make the tap or fountain inaccessible to children by disconnecting or bagging it until the problem is fixed. Other corrective actions can include increased flushing, replacing the fixture, or installing a filter or other device that is certified for lead reduction. Operators must also follow any other directions issued by their local medical officer of health.

The ministry recently released a technical bulletin: Adverse drinking water test results — reporting requirements and exemptions, which outlines information and rules on reporting adverse drinking water test results. This bulletin is intended to help owners of drinking water systems and licensed drinking water testing laboratories better understand their reporting requirements and when exceptions may apply.

Drinking water performance

The following section outlines the performance of regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, drinking water test results, and enforcement activities and programs in Ontario. The performance results show that Ontario’s drinking water systems continue to be well operated, and our water is still among the best protected in the world. More detailed information on the following data is available on the Ontario Data Catalogue.

| Category | Number of drinking water systems and laboratories |

|---|---|

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | 653 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems (for example, year-round trailer parks) | 434 |

| Systems serving designated facilities (for example, a school on its own well supply) | 1,373 |

| Licensed drinking water testing laboratories | 49 |

| Category | Number of tests results | Microbiological adverse test results | Chemical and radiological adverse test results | Percentage of test results meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | 528,852 | 489 | 179 | 99.87% |

| Non-municipal year-round residential systems | 43,514 | 73 | 71 | 99.67% |

| Systems serving designated facilities | 58,772 | 136 | 55 | 99.68% |

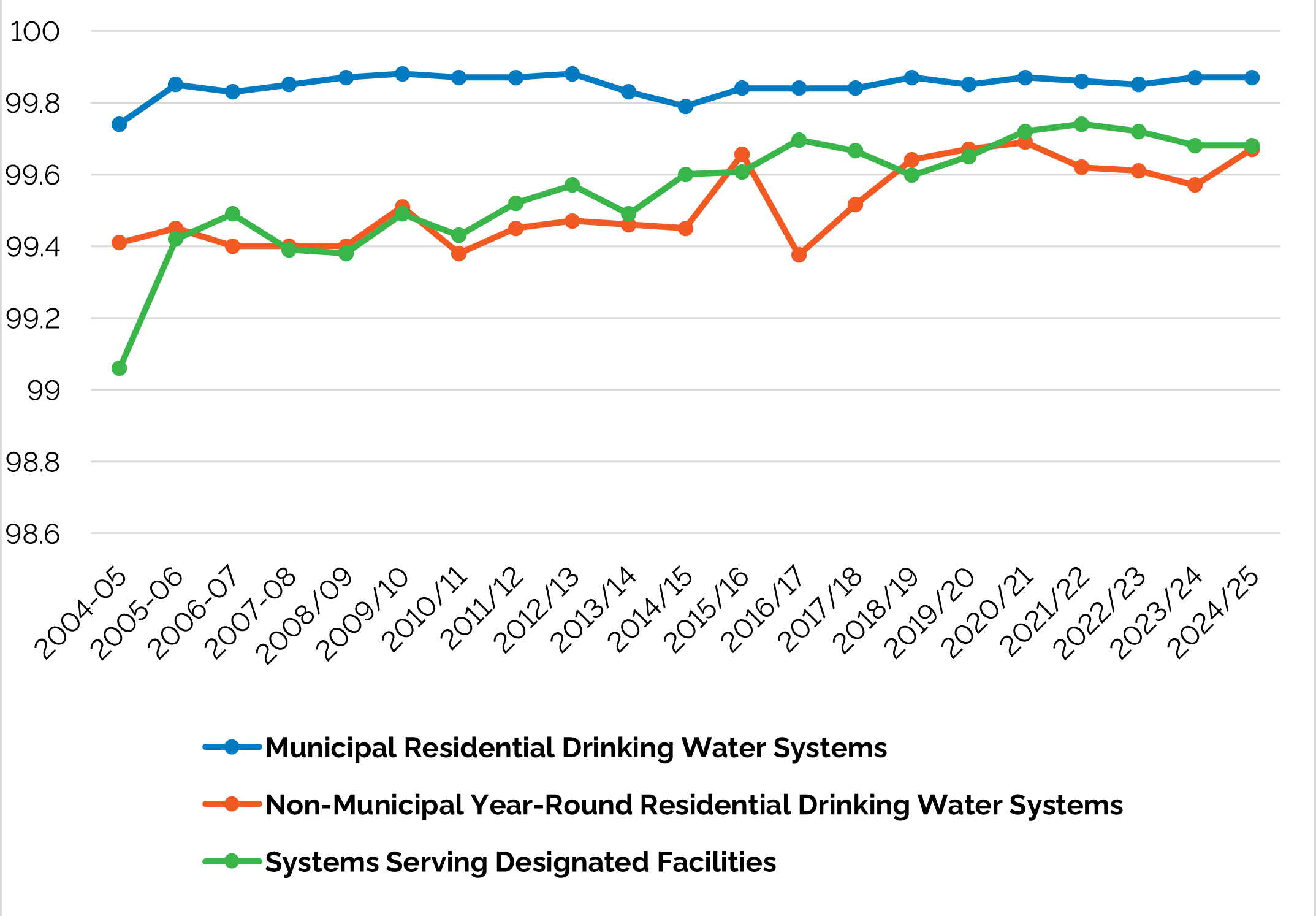

The consistent result of over 99% for all 3 system categories demonstrates that the stringent regulations and requirements in place help to ensure that regulated drinking water remains safe in Ontario. The year-over-year variation in the number of test results that met the drinking water quality standards is very minor, for all drinking water system categories. (Figure 3)

Total Summary: Percentage of test results that met the standardsfootnote 1

Figure 2: Trends in percentage of drinking water tests meeting Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards, by system type

A chart showing trends in the percentage of drinking water tests that met the standards for municipal residential drinking water systems, non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems, and systems serving designated facilities over 16 years. The trend is consistent for all 3 system categories, showing that over 99% of drinking water test results since 2004-2005 have met the standards.

For municipal residential drinking water systems, the percentage of drinking water test results that met the standards ranged from 99.74% in 2004-2005 to 99.87% in 2024-2025.

For non-municipal year-round drinking water systems, the percentage of drinking water test results that met the standards ranged from 99.41% in 2004-2005 to 99.67% in 2024-2025.

For systems serving designated facilities, the percentage of drinking water test results that met the standards ranged from 99.06% in 2004-2005 to 99.68% in 2024-2025.

| Category | Number of adverse water quality incidents | Number of systems reporting |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | 1,097 | 320 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential systems | 448 | 196 |

| Systems serving designated facilities | 337 | 245 |

| Sample type | Total number of results | Number of test results meeting Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards | Number of lead exceedances (of total number of results) | Percentage of test results meeting Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead — Flushed | 10,723 | 10,584 | 139 | 98.7% |

| Lead — Standing | 10,962 | 10,562 | 400 | 96.35% |

| Lead — Total for standing and flushed samples | 21,685 | 21,146 | 539 | 97.51% |

| Category | Number of test results | Percentage meeting the drinking water standard for lead |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | 4,680 | 95.94% |

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems | 540 | 99.81% |

| Category | Number of inspections |

|---|---|

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | 653 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems | 126 |

| Systems serving designated facilities | 261 |

| Schools and child care centres (lead) | 13 |

| Licensed drinking water testing laboratories | 97 |

| Category | Number of sent profile update reports |

|---|---|

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems | 455 |

| Drinking water systems serving designated facilities | 1,311 |

| Category | Number of facilities | Percentage of drinking water fixture inventories submitted | Percentage declaring sampling is completed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schools and child care centres | 11,131 | 97% | 87% |

Inspection ratings

The ministry assigns a rating to each inspection conducted at a municipal residential drinking water system or licensed drinking water testing laboratory. A risk-based inspection rating is calculated based on the number of non-compliance items identified during an inspection of a system or laboratory, and the significance of potential administrative, environmental, and/or health consequences associated with those non-compliances.

In 2024-2025:

- 76% of municipal residential drinking water systems received a 100% inspection rating

- 99.8% of municipal residential drinking water systems received an inspection rating above 80%

- 69% of laboratories received a 100% rating in at least 1 of their inspections

- 47% of laboratories received a 100% in both inspections

- 100% of laboratories received inspection ratings above 80%

An inspection rating of less than 100% does not necessarily indicate that drinking water is unsafe. It identifies areas where changes may be needed to improve the operation of a drinking water system or laboratory. In these situations, the ministry uses a range of compliance tools to help ensure that the owners address specific areas requiring attention.

Common instances of non-compliance for drinking water systems included failing to ensure that:

- continuous monitoring equipment is performing and recording tests correctly

- treatment equipment is properly operated (for example, using the correct dosage of chlorine, or confirming that filters are performing properly)

- logbooks are properly maintained and contain the required information

- persons operating the drinking water system possess the proper designation and training

- reporting requirements for adverse water quality incidents are met

- microbiological samples are collected at the proper frequency and correct location

Common instances of non-compliance for licensed laboratories included failing to ensure that:

- documentation and record-keeping contain sufficient detail

- policies and procedures are up to date

- laboratory personnel are conducting drinking water testing according to the licensed testing method

- adverse results are reported, and that the reports include all the required information

Compliance and Enforcement Regulation

The Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (Ontario Regulation 242/05) made under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 outlines the requirements the ministry’s compliance program must meet. Requirements met this year included:

In 2024-25, the ministry met these requirements by:

- completing an inspection at all municipal residential drinking water systems in the province

- completing 2 inspections at each of the licensed laboratories in the province

footnote 4 - conducting at least 1 of the 2 inspections at each licensed laboratory unannounced

- issuing all inspection reports for licensed laboratories within 45 days of the completion of the inspection

- taking mandatory action within 14 days of finding a deficiency at a municipal residential drinking water system or an infraction at a licensed laboratory

The ministry did not meet the requirement to conduct every third inspection of municipal drinking water systems unannounced, as one inspection was conducted announced when it should have been unannounced. The ministry also did not meet the requirement to issue all inspection reports for municipal residential drinking water systems within 45 days of the completion of the inspection, as one inspection report was issued after the 45-day requirement. The ministry took corrective action to help ensure that all requirements under the Compliance and Enforcement Regulation are met, including stricter adherence to standard operating procedures concerning these requirements. Training was provided to ministry staff on the importance of the Compliance and Enforcement Regulation and its requirements.

In addition to setting requirements for inspection and compliance activities, the Compliance and Enforcement regulation also provides the public with the right to request an investigation of an alleged contravention of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 or any of its regulations. In 2024-25, there were no public requests for such investigations.

Deficiencies and infractions

The Compliance and Enforcement regulation made under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 (Ontario Regulation 242/05) also requires that the ministry undertake mandatory action for deficiencies identified at municipal residential drinking water systems and infractions at drinking water testing laboratories. Mandatory action may consist of various measures, such as issuing an order with respect to the deficiency or requesting an investigation into non-compliant behaviour by the ministry’s Environmental Investigations and Enforcement branch.

A ‘deficiency’ in this context means a violation of prescribed provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 and its regulations that poses a drinking water health hazard. For example, water treatment equipment that is not operated according to provincial requirements may impact the quality of drinking water and adversely affect the health of those using the system. In the context of the Compliance and Enforcement regulation, an ‘infraction’ means a violation of prescribed provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 and its regulations in respect of a licensed laboratory. For example, in certain circumstances a laboratory’s failure to report an adverse test result to the owner of a drinking water system would constitute an infraction and could result in the system owner not taking corrective action.

In 2024-2025, the ministry did not identify any deficiencies during inspections of municipal residential drinking water systems.

There were three infractions identified at three licensed laboratories.

The following orders were issued by the ministry in 2024-2025 (including those issued with respect to an infraction):

Licensed laboratories

Three orders were issued to licensed laboratories, requiring actions to address:

- a laboratory that offered and provided drinking water testing services that were not authorized by the laboratory’s drinking water testing licence

- a laboratory whose licence was suspended because the laboratory was no longer accredited to provide drinking water testing services by an accreditation body designated under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 yet it was still conducting drinking water testing

- a laboratory that failed to immediately report an adverse test result to the Ministry of Health

The laboratories complied with the orders.

Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems

Eight orders were issued to the owners of non-municipal year-round residential systems, requiring actions to address non-compliance at:

- a duplex complex where record keeping, sampling and testing for chlorine residual and raw turbidity, and equipment maintenance and checks were not being performed as required

- a trailer park where the owner did not have a certified operator, as required, and did not ensure that system monitoring and maintenance or microbiological sampling were performed as required

- a trailer park and campground where the drinking water system category had changed, and the owner failed to: register the system with the ministry; retain a licensed engineering practitioner to prepare an engineering evaluation report; and retain a certified operator to operate and maintain the system

- an apartment building where the owner did not have a certified operator conducting maintenance on the drinking water system as required

- a trailer park and campground where the owner was no longer retaining a certified operator to operate the system as required

- a campground and mobile home park where the owner was not maintaining the drinking water system in a fit state of repair, and was not retaining a certified operator to operate it and perform sampling as required

- a trailer park where the owner did not obtain an Engineering Evaluation Report nor ensure that the proper maintenance, operation, and minimum level of treatment were provided as required

- an apartment building where the owner did not ensure that the operator was properly certified to operate the system as required

Four owners complied with the orders within the timeframe outlined in the orders. Four orderees failed to comply with the orders and an investigation was requested.

Systems serving designated facilities

Six orders were issued to owners of systems serving designated facilities, requiring actions to address non-compliance at:

- a supportive housing facility where the owner lacked a trained person to operate and maintain the drinking water system as required

- a children's camp where the drinking water system owner was not ensuring proper raw water and distribution system sampling or minimum level of treatment, and was not satisfying requirements related to operations and maintenance, annual reports, alarm responses, and incident reporting

- a children's camp where the owner was not properly conducting or documenting nitrate/nitrite sampling, and not satisfying requirements related to the system’s annual reports or Engineering Evaluation Reports

- a children's camp where the owner was not maintaining the well properly, did not ensure qualified staff were operating the system, and did not ensure that UV unit alarms were addressed as required

- a private school where the owner was not retaining a properly qualified person to conduct free chlorine residual monitoring

- a senior's residence where the owner was not ensuring that properly qualified staff operated the system, nor maintaining the system, achieving primary disinfection, conducting proper sampling, or responding to adverse water quality incidents as required

Four owners complied with the orders within the timeframe outlined in the orders. One orderee partially complied with the order and the ministry continues to follow-up with that owner. Another orderee failed to comply with the order and an investigation was requested.

More details on the actions ordered is available on the Ontario Data Catalogue.

Section 114 Order

Section 114 of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 sets out circumstances where a ministry Director can require a municipality to provide service to or assume responsibility for a non-municipal drinking water system to address or prevent a drinking water health hazard at a non-municipal drinking water system serving a major residential development. Prior to the issuance of a Section 114 order, the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 requires that the Director:

- consult with the medical officer of health

- give notice to the municipality of his or her intention to issue an order to provide service, and give written reasons in the notice for the proposed order

- provide the municipality with the opportunity to submit a written response to the Director and the medical officer of health before the order is issued

Before 2024, the operating authority of a non-municipal year-round residential drinking water system servicing approximately 60 homes and other non-residential properties informed the ministry that it anticipated needing to cease operating the drinking water system and that it had no successor. The local municipal actors recognized that it would be in the best interest of the residents to be serviced by a municipal residential drinking water system. In 2024–2025, the ministry utilized Section 114 of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 to require the local regional municipality and township to provide service to the users of the drinking water system going forward. The status of the drinking water system changed from non-municipal to municipal.

Convictions

In 2024-2025, owners, operating authorities, and/or operators of 5 systems that supplied drinking water to municipal and non-municipal residential systems and a designated facility were convicted and fined for a combined total of $87,500, with respect to charges for various offences under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002.

These convictions were as follows:

Municipal residential drinking water systems

- The owner of a municipal residential drinking water system was convicted for failing to meet sampling/testing requirements for the distribution system free chlorine residual. The free chlorine was not measured at least once daily nor were the prescribed rules followed. The owner pleaded guilty and was fined $5,000, plus the Victim Fine Surcharge.

Non-municipal year-round residential systems

- The operating authority of a drinking water system for a residential townhome complex was convicted for failing to ensure that every operator employed in the subsystem held the proper certification and for failing to ensure that distribution microbiological samples were taken and tested as required. The operating authority pleaded guilty and was fined $18,000, plus the Victim Fine Surcharge.

- The corporate owner and director of a modular home village were convicted for failing to comply with a ministry order by failing to retain the services of a certified operator or operating authority for the drinking water system by the compliance deadline. They were also convicted for failing to ensure that water treatment equipment was operated as required to ensure adequate disinfection within the distribution system so that, at all times and at all locations within the distribution system, the free chlorine residual was never less than 0.05 milligrams per litre. The corporation and its director pleaded guilty and were fined $45,000 in total, plus Victim Fine Surcharge.

- The owner of an apartment building’s drinking water system was convicted for failing to ensure that the system was operated by a certified drinking water operator and for failing to ensure that distribution microbiological samples were taken as required. The owner pleaded guilty and was fined $10,000 in total, plus Victim Fine Surcharge.

Designated facility

- The owner and operating authority of a drinking water system for a private school were convicted for failing to ensure that the drinking water system was operated by persons having the training or expertise required by the regulations, and for failing to ensure that raw and distribution microbiological samples were taken as required. The operator of the school was also convicted for failing to ensure that samples of water were taken and tested for lead. The owner, operating authority, and operator pleaded guilty and were fined $9,500 in total, plus the Victim Fine Surcharge.

All issues of non-compliance that led to these convictions have been resolved.

Information on drinking water quality, inspections, orders and convictions data is available on the Ontario Data Catalogue.

2024-2025 highlights of Ontario’s small drinking water system results

Across Ontario, thousands of businesses and other community sites use small drinking water systems to supply drinking water to the public. These places may not have access to a municipal drinking water supply and are most often located in semi-rural and remote communities.

These small drinking water systems, which are regulated under the Health Protection and Promotion Act and one of its regulations, Ontario Regulation 319/08 (Small Drinking Water Systems), provide drinking water in restaurants, medical offices, places of worship and community centres, resorts, rental cabins, motels, lodges, bed and breakfasts, campgrounds, and other public settings.

The Small Drinking Water System Program is a unique and innovative program overseen by the Ministry of Health and administered by local boards of health. Public health inspectors conduct inspections and risk assessments of all small drinking water systems in Ontario, and provide owner/operators with a tailored, site-specific plan (i.e., a Directive) to help keep drinking water safe. This customized approach has reduced unnecessary burden on small drinking water system owner/operators without compromising provincial drinking water standards.

Owners and operators of small drinking water systems are responsible for protecting the drinking water that they provide to the public. They are also responsible for meeting various regulatory requirements, including regular drinking water sampling and testing, and maintaining up-to-date records.

2024-25 at a glance:

- Over the past decade, we have seen increasingly positive results including a steady decline in the proportion of high-risk systems (7.85% in 2024-25 down from 16.65% in 2012-13). The total number of systems is relatively stable year over year.

- Risk category is determined based on water source, treatment, and distribution criteria. High-risk small drinking water systems may have a significant level of risk and are routinely inspected every two years. Low and moderate risk small drinking water systems may have negligible to moderate risk levels and are routinely inspected every four years.

- Public health inspectors often work with the operator to address potential risks, which, when corrected, may result in a lower assigned category of risk.

- As of March 31, 2025, 80.4% of small drinking water systems are categorized as low risk and a total of 92.15% of systems are categorized as low and moderate risk, and subject to regular re-assessment every four years. The remaining systems, categorized as high risk, are re-assessed every two years.

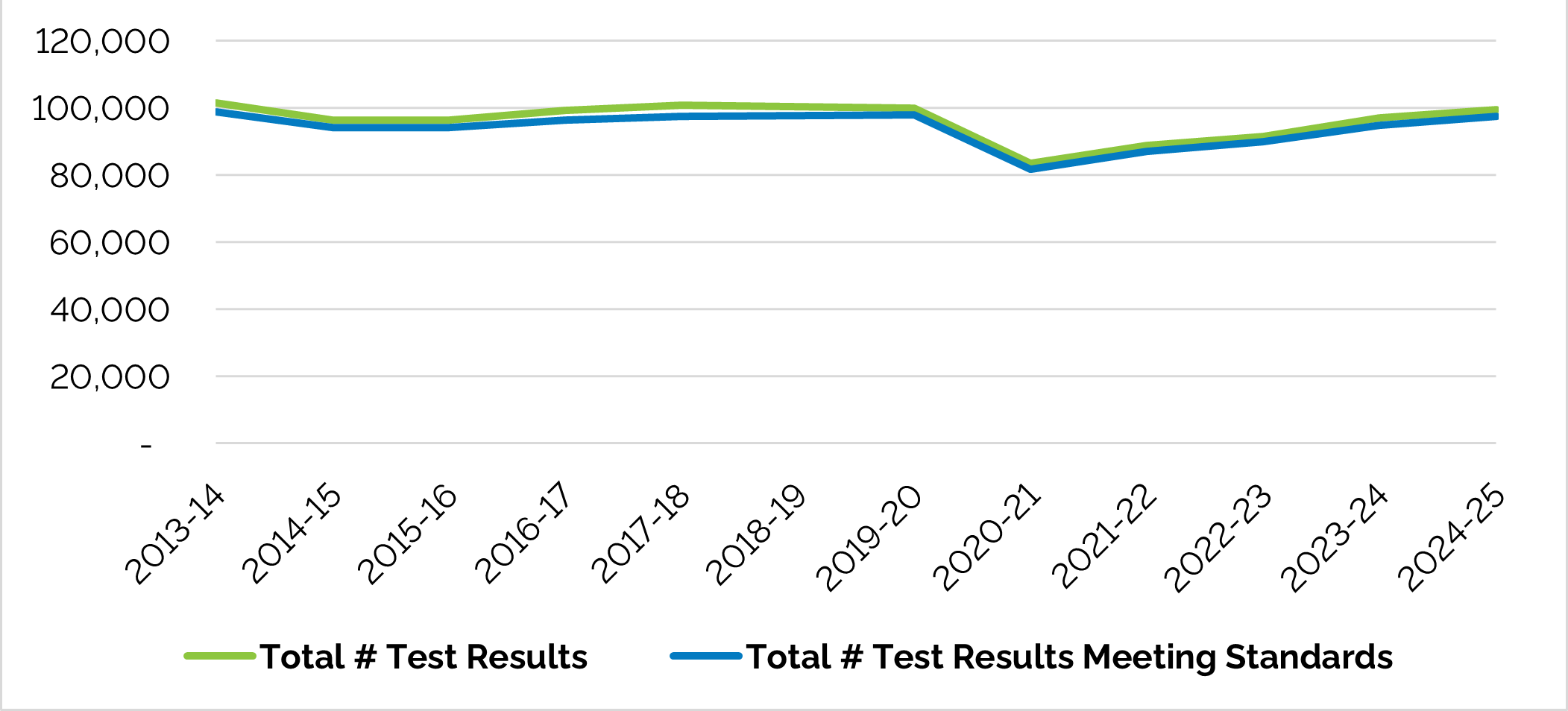

- Sampling continues to return to pre-pandemic levels, with 50,326 samples submitted to licensed laboratories and 99,273 test results received in 2024-25, after a decline between 2020 and 2021.

- 98.13% of the nearly 100,000 drinking water test results for small drinking water systems during the reporting year have consistently met Ontario drinking water quality standards as set out in Ontario Regulation 169/03 made under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002. Public health inspectors work with the system owners and operators to bring their systems into compliance.

- As of March 31, 2025, 29,549

footnote 5 risk assessments have been completed for the approximately 10,000 small drinking water systems since the inception of the current program in December 2008. The risk assessment is used by the public health inspector to develop the directive for the system which is a site-specific plan for the operator. The directive may include requirements regarding:- the frequency and location of sampling

- water samples to be taken and tested for biological, chemical, radiological, or other potential contamination

- operational tests such as checking disinfection levels and conducting turbidity tests

- operator training

- record-keeping

- installation of treatment equipment

- posting and maintaining warning signs

- Through the Ministry of Health’s Small Drinking Water System Program, local public health units provide information to small drinking water system owners and operators on:

- how to protect their drinking water at the source by identifying possible contaminants

- how and when to test their water

- treatment options and maintenance of treatment equipment, where necessary

- when and how to notify the public, whether in relation to a poor water sample test result or equipment that is not working properly

- what actions need to be taken to mitigate the problem

In the event of an adverse test result, the laboratory involved will notify both the owner/operator of the small drinking water system and the local public health unit for immediate response to the incident. Details of the adverse water quality incident will also be tracked by the public health unit in the Drinking Water Advisory Reporting System.

Adverse water quality incidents can result from an observation (for example, an observation of treatment malfunction) or adverse test result (i.e., water sample does not meet drinking water standards under Ontario Regulation 169/03).

- Since 2013-2014, a significant downward trend in both total adverse water quality incidents and the number of systems that reported an adverse water quality incident has occurred, with some fluctuations (most notably during the COVID pandemic):

- In the past two years, adverse drinking water quality incidents (AWQIs) and number of small drinking water systems with an AWQI, which had decreased during the COVID pandemic, have recovered and reflect pre-pandemic data trends.

footnote 6 - For example, in 2024-25, there were a total of 1,058 adverse water quality incidents reported by 785 small drinking water systems. These values decreased approximately 10% and 8% respectively from the previous year (despite a slight increase in samples and test results).

- Overall, the total number of incidents in 2024-25 is down 30.26%; and 35.44% fewer systems reported an adverse water quality incident compared to 2013-2014 data, at 1,517 adverse water quality incidents for 1,216 systems.

- Over the last three years, 2022-23 to 2024-25, the proportion of total AWQIs identified by an observation or another means, versus an adverse test result, has been the highest (approximately 19%) since the small drinking water systems program was implemented. This trend may be attributed to small drinking water systems operators’ increased awareness and knowledge.

A chart showing trends in the total number of small drinking water system test results and those results that met the Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards from 2013-14 to 2024-25.

The small drinking water system adverse water quality incident data demonstrates the success of the Small Drinking Water System Program. Adverse incidents are now being systematically captured and appropriate action can now be taken and tracked to help protect drinking water users.

Reductions in adverse water quality incidents in small drinking water systems have occurred over time since the start of the program, as owners/operators have complied with sampling requirements in accordance with their directives and have instituted improvements in their drinking water systems.

Note, the Ministry of Health is not aware of any reported illnesses related to these incidents. This may in part be because, through the Small Drinking Water System Program, operators now know when and how to notify users that their drinking water may not be safe to drink and are working with public health units to take appropriate corrective actions to mitigate any potential problems.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph There were slight variations in the methods used to tabulate the percentages year-over-year due to regulatory changes and different counting methods.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph A tailored report, which summarized systems’ profile data available to the ministry, to help keep system profile information up-to-date.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph The ministry is following up with the rest of school and child care centre operators to determine whether they met the requirement to sample all fixtures.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph Note: one laboratory had its licence suspended mid-year and so did not require a second inspection.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph The reported number of risk assessments will change as new systems come into use/change in use, and routine re-inspections and risk assessments are completed. Risk categories may also fluctuate (for example, if recommended improvements are taken to reduce the system’s risk). Similarly, a system may require reassessment to determine if the risk level has changed (for example, if the water source or system integrity is affected by adverse weather events or system modifications).

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph An adverse test result does not necessarily mean that users are at risk of becoming ill. When an adverse water quality incident is detected, the small drinking water system owner/operator is required to notify the local medical officer of health and to follow up with any action that may be required. The public health unit will perform a risk analysis and determine if the water poses a risk to health if consumed or used and may take additional action as required to inform and protect the public. Response to an adverse water quality incident may include issuing a drinking water advisory that will notify potential users if the water is safe to use and drink or if it requires boiling to render it safe for use. The public health unit may also provide the owners and/or operators of a drinking water system with necessary corrective action(s) to be taken on the affected drinking water system to address the risk.