Barn Swallow Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the Barn Swallow, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) in Ontario

Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

2014

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There was a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage at: www.ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Heagy, A., D. Badzinski, D. Bradley, M. Falconer, J. McCracken, R.A. Reid and K. Richardson. 2014. Recovery Strategy for the Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. vii + 64 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2014

ISBN 978-1-4606-3079-2 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n'est disponible qu'en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Michelle Collins au ministère des Richesses naturelles et des Forêts au

Authors

Audrey Heagy Bird – Studies Canada, Port Rowan, ON

Debbie Badzinski – Bird Studies Canada, Ottawa, ON

David Bradley – Bird Studies Canada and University of Guelph, Guelph, ON

Myles Falconer – Bird Studies Canada, Port Rowan, ON

Jon McCracken – Bird Studies Canada, Port Rowan, ON

Ron Reid – Bobolink Enterprises, Washago, ON

Kristyn Richardson – Bird Studies Canada, Port Rowan, ON

Acknowledgments

Funding for the preparation of this recovery strategy was provided by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF) through a contract to Bird Studies Canada (BSC). Many thanks to Vivian Brownell (OMNRF) for overseeing project delivery.

We would like to thank all of the people who participated in the technical workshops held at Guelph, Ontario on 10 December 2012 and 12 August 2013. Their names and affiliations are as follows:

Amelia Argue – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Natalie Boyd – Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Kyle Breault – Tallgrass Ontario

Chris Brown – Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Vivian Brownell – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Jennifer Brownlee – Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Mike Cadman – Environment Canada

Anthony Chegahno – Neyaashiinigming First Nation

Glenn Desy Ontario – Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Nancy Furber Haldimand – Bird Observatory

Cathy Giesbrecht – Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Jenny den Hartog – Christian Farmers Federation of Ontario

Gail Jackson Ontario – Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Peter Jeffery – Ontario Federation of Agriculture

Leanne Jennings – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Nicole Kopysh – Canadian Wind Energy Association

Rod Krick – Credit Valley Conservation

Zoé Lebrun-Southcott – Bird Studies Canada, Barn Swallow Project Biologist

Barb Macdonnell – Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Hannah MacIver – Environmental Consultant

Rob MacIver – Ontario Field Ornithologists

Megan McAndrew – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Lisa Myslicki – Infrastructure Ontario

Michael Patrikeev – Parks Canada, Bruce Peninsula National Park

Mark Peck – Royal Ontario Museum

Sarah Plant – Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

Bill Read – Ontario Eastern Bluebird Society

Chris Risley – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Peter Roberts – Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

Antonio Salvadori – Ontario Bird Banding Association (Wellington County Barn Swallow banding project)

Larry Sarris – Ontario Ministry of Transportation Andrew Sawyer Bruce Peninsula Bird Observatory Adrian Sgoifo Ontario Ministry of Transportation John Small Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Paul Smith – Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

Sean Spisani – Environmental Consultant

Nathan Stevens – Christian Farmers Federation of Ontario

Bridget Stutchbury – York University

Sandra Turner – Ruthven Park

Mary Young – Ontario Ministry of Transportation

In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge the technical information and assistance provided by David Bell, Peter Blancher (Environment Canada, Partners in Flight), Graham Bryan (Environment Canada), Andrew Couturier (Bird Studies Canada), Marie-Anne Hudson (Environment Canada), Adam Smith (Environment Canada), Ron Tozer (Algonquin Park) and Richard A. Wolinksi (Michigan Department of Transportation).

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Barn Swallow was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

The Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) is a medium-sized migratory songbird found in open country habitats. The most abundant and widespread swallow in the world, this familiar species breeds in temperate regions across North America, Europe and Asia, and overwinters in Central and South America, southern Africa, and southern and southeast Asia. Throughout its range, it is found in close association with human populations. Six subspecies of Barn Swallow are recognized but only one subspecies, H.r. erythrogaster, breeds in North America. Due to population declines across the northern portion of its North American breeding range, the Barn Swallow is listed as threatened under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and has been designated as threatened in Canada by COSEWIC. The Barn Swallow is one of many diverse species of common aerial-foraging insectivorous birds that are of conservation concern in Ontario, Canada and the northeastern United States due to long-term population declines for a combination of reasons that are not well understood.

This species breeds throughout Ontario but over 90 percent of the provincial population (ca. 350,000 individuals) is concentrated in southern Ontario, south of the Canadian Shield. Its distribution in northern Ontario is localized, being closely associated with roads and human settlements and largely absent in more remote areas. Since 1970 the Ontario Barn Swallow population has declined at an average annual rate of 2.56 percent, amounting to a cumulative loss of 66 percent. The rate of decline over the most recent 10-year period is similar to that since 1970.

Barn Swallow habitat needs include foraging habitat, nest sites and nests and nocturnal roost sites. Across Ontario Barn Swallows forage over a wide range of open country habitats including farmland, lakeshore and riparian habitats, road right-of-ways, clearings in wooded areas, parkland, urban and rural residential areas, wetlands and tundra. Barn Swallow nests in Ontario are commonly situated inside or outside of buildings, under bridges and wharves and in road culverts. A small portion of the population nests on cliff faces. Outside of the breeding season swallows congregate nightly in communal roosts. Roost sites in Ontario are often associated with marshes or shrub thickets in or near water.

Numerous factors have been proposed as possible explanations for the recent declines in Barn Swallows and other aerial insectivores. The information needed to critically evaluate known and potential threats to Barn Swallows in Ontario is generally lacking. Many knowledge gaps must be addressed in order to understand the most significant threats to this species' survival. It is likely that multiple direct and indirect threats at various stages (and locations) in its life cycle along with population fluctuations due to natural processes, are having an additive or synergistic impact on Barn Swallow populations.

Known and potential direct and indirect threats affecting reproduction and survival include: (1) loss of nest site habitat, (2) loss or degradation of foraging habitat, (3) environmental contaminants, pesticides and pollution, (4) reduced productivity due to predation, parasitism and persecution, (5) habitat loss, disturbance and human persecution at roost sites, and (6) climate change and severe weather.

Lack of understanding of the causes of the population decline hampers recovery planning. Key knowledge gaps that must be addressed to focus recovery efforts include: (1) vital rates and population source/sink dynamics, (2) diet and food supply, (3) habitat use, requirements and trends in Ontario, (4) wintering and migration habitat and ecology, (5) best management practices, and (6) climate change effects.

The recovery goal is to maintain a stable, self-sustaining population of Barn Swallow in Ontario by 2034 (within 20 years) and to slow the rate of decline over the next 10 years. The recovery objectives identified in this strategy are to:

- fill key knowledge gaps to increase understanding of the nature and significance of threats to Ontario Barn Swallow populations and the biological and socio-economic factors that may impede or assist recovery efforts;

- maintain or improve nesting productivity through the development of appropriate practices and policies for managing Barn Swallow nests, nest sites and associated foraging habitat in Ontario;

- promote stewardship, education and increased public awareness of the Barn Swallow in Ontario;

- identify and protect important roost sites used by Barn Swallows in Ontario; and

- inventory, monitor and report on the state of Barn Swallow breeding populations and habitats in Ontario and elsewhere to track the progress of recovery activitie

Approaches to recovery focus on research to address key knowledge gaps and also a range of short-term activities designed to maintain, and where possible enhance the reproductive output of the breeding population.

It is recommended that until key knowledge gaps are addressed, habitat for Barn Swallow in Ontario be defined narrowly as follows:

- nests (including unused nests) on natural or human-created nest sites during the current breeding season (between May 1 and August 31) plus the area within 1.5 m of the nest and the openings the birds use to access nests in enclosed situations;

- all used nests at any nest site that has been occupied by Barn Swallows within the previous three breeding seasons; and

- significant roost sites that are used regularly by at least 5,000 birds (approximately 1% of Ontario’s breeding population, adjusted for young-of-the-year) during the post-breeding season (July 1 through October 31).

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name (population):

Barn Swallow

Scientific name:

Hirundo rustica

SARO List Classification:

Threatened

SARO List History:

Threatened (2012)

COSEWIC Assessment History:

Threatened (2011)

SARA Schedule 1:

No Status

Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5

NRANK: N4N5B

SRANK: S4B

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

The Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) is a medium-sized songbird (length: 15-18 cm, mass: 17-20 g) with a long forked tail. Adults have steely-blue upperparts, cinnamon underparts, and a chestnut throat and forehead. Plumage of the sexes is similar but the elongated outer tail feathers are particularly noticeable on adult males (outer tail feather length 79-106 mm in males versus 68-84 mm in females; Pyle 1997).

This species can be distinguished readily in all plumages and ages from other North American swallows by its deeply forked tail, the white spots on the inner webs of the tail feathers and extensive cinnamon underparts (Godfrey 1986, Brown and Brown 1999a).

Six subspecies of Barn Swallow are recognized in the world and can be visually distinguished by subtle differences in plumage characteristics. Only one subspecies, H.r. erythrogaster, breeds in North America (Brown and Brown 1999a).

Species biology

Many aspects of Barn Swallow biology have been intensively studied, particularly the life history of the H.r. rustica subspecies, which breeds in Europe and winters in Africa. Caution is needed in applying the results of European studies to Barn Swallows in Ontario as there are some notable differences in the breeding biology of North American and European subspecies (Brown and Brown 1999a). For example, H.r. erythrogaster males participate in incubation whereas H.r. rustica males do not (Smith and Montgomerie 1991), and European birds can produce up to three broods per year, whereas there are no records of North American birds raising more than two broods in a year (Brown and Brown 1999a, Turner 2004). Also most breeding studies in Europe have focussed on birds nesting in dairy barns and other farm buildings where conditions may not be comparable to the range of breeding sites used in Ontario. In this recovery strategy, information for the North American subspecies is provided where available.

Food habits

The Barn Swallow is the archetypal member of the guild of aerial-foraging insectivorous birds characterized by their habit of feeding on insects while in flight. This familiar diurnal species is often observed feeding on insects flushed by grazing mammals, farm tractors, humans or flocks of other bird species (Brown and Brown 1999a). Occasionally, they land on the ground to pick up dead insects or pick insects from plants, buildings or water surfaces while in flight.

Barn Swallows forage individually or in small groups usually within 10 m of the ground in open areas (Brown and Brown 1999a). In cold weather Barn Swallows will sometimes forage in large numbers at ponds and lakes where the warmer water temperatures keep flying insects active (COSEWIC 2011).

During the breeding season most foraging takes place within 600 m of the nest site (Turner 2004). Information on foraging distances at other times of the year is currently not available.

Prey items consist almost entirely of flying insects. They also ingest grit, apparently to aid digestion of insects and possibly also for calcium (Brown and Brown 1999a). Diet reflects local insect availability with more than 80 insect families recorded as prey in European studies (Brown and Brown 1999a). Flies (Diptera) are the most common food item reported in North America along with beetles (Coleoptera), true bugs (Hemiptera), leafhoppers (Homoptera) and bees, wasps and ants (Hymenoptera; Brown and Brown 1999a). Barn Swallows often feed on single, large insects rather than on insect swarms (Brown and Brown 1999a).

Reproduction

Barn Swallows are usually socially monogamous but extra-pair paternity is common (Smith et al. 1991). Females typically first breed when one year old. Some yearling males may remain unpaired (Turner 2004). Breeding pairs are established after arrival on the breeding grounds. Pairs that nested successfully in the previous year often remain together (Shields 1984).

Barn Swallows will nest in solitary situations but are more frequently colonial with multiple pairs nesting on a single nesting structure (Brown and Brown 1999a). Barn Swallows defend a small territory (eight square metres or less in a European study) around their nest (Brown and Brown 1999a). Inter-nest distances in colonies are typically two to four metres but can be less than one metre apart if there is a visual obstruction between nests (Brown and Brown 1999a, Mercadante and Stanback 2011).

Nest record data indicate that colonies in Ontario range from 2 to 59 nests, with an average size of 10 nests (n=161) (Peck and James 1987). Colonies of up to 83 pairs have been reported elsewhere in Canada (Campbell et al. 1997).

The cup-shaped nests are made of mud pellets and lined with grasses and feathers (Brown and Brown 1999a). Nest construction starts soon after the birds return to their breeding grounds (Brown and Brown 1999a). Nest building takes 6 to 15 days (COSEWIC 2011). Old nests are often repaired and reused, which requires less time and effort than building a new nest (Brown and Brown 1999a, Turner 2006).

Egg dates for nests in Ontario range from 10 May to 21 August (Peck and James 1987). Egg-laying within a colony is largely asynchronous (Brown and Brown 1999a).

Clutch size is generally four or five eggs in Ontario ranging from one to seven (n=467) (Peck and James 1987). First clutches are larger than second clutches (Brown and Brown 1999a). Cowbird parasitism rates are negligible (4 of 3205 nests in Ontario; Peck and James 1987).

The incubation period is generally 13 to 14 days in Ontario (Peck and James 1987), and is performed mostly by the female (Smith and Montgomerie 1991). Eggs usually hatch within a 24 hour period (Brown and Brown 1999a).

Both parents feed nestlings, largely in equal proportions in North American subspecies (Brown and Brown 1999a). Young leave the nest when 19 to 24 days old (Brown and Brown 1999a) but may fledge prematurely by day 14 if handled or otherwise disturbed (Anthony and Ely 1976). Young are fed by their parents for up to a week after fledging and return to the nest at night for several days (Brown and Brown 1999a).

Second broods are common in Ontario and usually occur in the same nest (Peck and James 1987). The average interval between initiation of the first and second clutch is poorly understood but reported as about 51 days for birds in British Columbia (Campbell et al. 1997).

Nest success in this species is generally high (approximately 70-90% of nests fledge at least one young in Ontario and elsewhere), although ectoparasites, local predation or inclement weather conditions can negatively impact nest success (Turner 2004, Turner and Kopachena 2009, Salvadori 2009).

One Ontario study involving 20 pairs found that first broods had an average of 3.1 fledglings, 30 percent of the pairs laid a second clutch and the estimated annual reproductive success was 4.2 fledglings per pair (Smith and Montgomerie 1991). In contrast a Manitoba study at a site with high insect abundance found that 90 percent of pairs produced two broods and the annual reproductive success of 21 pairs was 6.9 fledglings per pair (Barclay 1988). Nest productivity, frequency of second broods, and annual reproductive rates reported elsewhere are also quite variable between sites and between years (Turner and Kopachena 2009). The average number of fledglings per pair per year ranged from 4.2 to 7.1 in studies from across the global range (Turner 2004).

Roosts

Outside of the breeding season Barn Swallows and other North American swallows forage widely during the day and congregate nightly in dense communal roosts (Winkler 2006). In Ontario, bird numbers at swallow roosts start to build up in July, peak in early to mid-August and are negligible by September (Clark 1984, Ross et al. 1984, Long Point Bird Observatory unpub. data).

These post-breeding roosts often include a mix of swallow species and it is difficult to accurately estimate the number of each species, which vary seasonally (Ross et al. 1984). Peak counts of up to 25,000 Barn Swallows have been reported in Ontario (Godwin 1995, Weir 2008). Counts of over 100,000 birds, including a mix of Barn Swallows and other swallow species, were reported at a swallow roost on a small island at Pembroke, Ontario that was occupied annually for more than 20 years and became the focus of an annual summer festival (Clark 1984, Ross et al. 1984, Ottawa River Legacy Landmark Partners n.d.).

Information on roosting behaviour and roost locations during migration and winter for Barn Swallows in the Americas is very limited. Radar data indicate that during migration periods swallow roosts in North America tend to be spaced about 100 to 150 km apart and that there is considerable variation in how consistently these migratory roost locations are used from year to year (Winkler 2006). Though they likely exist, no major Barn Swallow roost sites have yet been documented on their wintering grounds in Central or South America.

Extensive European banding studies show that the dynamics of Barn Swallow roosts vary seasonally with high rates of turnover of individuals during migration and longer stopover times during the post-breeding and wintering periods (Pilastro and Magnani 1997, Rubolini et al. 2002, Halmos et al. 2010, Coffait et al. 2011, Neubauer et al. 2012). Individual winter roosts in excess of one million birds (H.r. rustica) that are used annually have been reported at three sites in Africa (BirdLife International 2013a, b, c).

Migrations

Barn Swallows are long-distance migrants, flying more than 8,000 km between their breeding sites and wintering grounds. Long distance movements include a marked bird that moved 12,000 km in 34 days (320 km/d average) and another that moved 3,028 km in 7 days (433 km/d; Turner 2004).

Barn Swallows migrate during the day in loose flocks, often following coastlines or river valleys (Bent 1942). During migration swallows forage as they fly and shift from one nocturnal roost site to the next (Winkler 2006). They accumulate fat reserves prior to migration and are capable of extended flights across water and other ecological barriers (Pilastro and Magnani 1997, Pilastro and Spina 1999, Rubolini et al. 2002, Halmos et al. 2010, Coffait et al. 2011).

Most Barn Swallows depart Ontario by late September with small numbers present locally through October. In spring Barn Swallows return to southern Ontario starting in April with the main passage occurring in May. The frequency with which this species is reported on eBird checklists for Ontario (1900-October 2013; N=275,541) shows a bimodal distribution with a spring migration peak on 11 May (36.2% of checklists) and a late summer peak on 7 August (29.3% of checklists) (eBird, unpub. data 2013). The mass arrival and departure dates, calculated as the earliest and latest dates with 20 percent of the peak checklist frequency (Iliff et al. 2011) for Barn Swallows in Ontario are April 15 and September 11 respectively (M.Burrell, pers. comm. 2013). The wintering grounds and migration routes of the Barn Swallows that breed in Ontario are not known (see section 1.7 for current research project).

Relatively little is known about the phenology, movements and biology of the North American Barn Swallow population outside of the breeding season. The three foreign encounters of banded birds from the Ontario population have been in the United States. A bird banded in New Jersey on spring migration was reported the following year in Ontario and two birds banded in Ontario were subsequently encountered on fall migration in Louisiana and Massachusetts, respectively (Brewer et al. 2000).

Observations and band recoveries suggest that the bulk of the North American Barn Swallow population migrates through the Central American isthmus although trans-Gulf and trans-Caribbean migration routes have also been reported (Brown and Brown 1999a, Winkler 2006). In contrast there is considerable information on the migration routes and non-breeding biology of European Barn Swallows due to intensive roost banding projects such as the collaborative European Union for Bird Ringing (EURING) Swallow Project (Spina 2001).

Demography, site fidelity, and dispersal

Limited information is available on the demography, site fidelity and dispersal patterns for the Ontario and North American population compared to European birds as there have been few long-term, intensive Barn Swallow banding projects on this continent. The largest banding project in Ontario has focussed on Barn Swallows breeding in barns and other buildings at up to 21 locations in Wellington County since 2008 (Salvadori 2009, Salvadori et al. 2011).

The Barn Swallow is a short-lived species with most individuals living for less than four years (Turner and Rose 1989, Saino et al. 2012). The longevity record for North America is eight years, one month (Clapp et al. 1983, Lutmerding and Love 2012).

The age structure of the breeding population cannot be determined except in marked populations, as Barn Swallows undergo a complete moult in their first year and yearlings cannot be distinguished from older birds by plumage or other characteristics (Pyle 1997). Return rates of birds banded as adults at breeding sites vary considerably by year and location, ranging between 12 percent and 42 percent in North American studies (Brown and Brown 1999a).

Adults show very strong fidelity to breeding sites typically with more than 99 percent of returning adults using the same site and many returning to the same nest in consecutive years (Brown and Brown 1999a, Turner 2004, Safran 2004). However, Barn Swallow yearlings seldom return to their birthplace and few settle at nest sites within 30 km of their natal site (Shields 1984, Turner and Rose 1989, Brown and Brown 1999a, Balbontín et al. 2009a). Dispersal distances and survival rates for young birds cannot be estimated from local or regional banding studies because most birds banded as nestlings that survive and return as yearlings presumably settle at sites outside of the study area (Balbontín et al. 2009a).

The Wellington County, Ontario study (Salvadori 2009) reported that at least 103 of 493 (20.8 %) banded adults returned to the same nesting site in the following years (actual return rate is higher as not all adults were captured each year; A. Salvadori, pers. comm. 2012). One bird in this study returned for seven consecutive years (Salvadori 2009). Only one re-captured adult (0.12 %) changed sites between years (Salvadori 2009). Of 4,147 birds banded as nestlings at 21 locations in Wellington County, 29 (0.7%) were subsequently recaptured as breeding birds at the same location, and 5 (0.12%) returned to a different location within the study area (Salvadori 2009). These findings are generally consistent with similar banding studies done elsewhere.

A study of the effect of nest removal (Safran 2004) found that the site fidelity of returning adults was not affected by the removal of all old nests (i.e., no adults changed sites). However, this study did find a strong relationship between the number of old nests at a site at the start of the breeding season and the number of immigrants (yearling females) that settled at those sites, indicating that used nests serve as an important cue for yearling females selecting their initial breeding location (Safran 2004, 2007). Removal of old nests reduces the number of pairs using a nest site and also results in a higher proportion of experienced females at the site (as fewer yearling females are recruited).

Mean annual adult survival probability for birds nesting at a large colony in Nebraska was 0.350 ± 0.054 SE (n=300) (Brown and Brown 1999a) and 0.38 ± 0.13 SE in a New York study (Safran 2004). Annual adult apparent survival for 21 constant effort banding stations (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship network) from across North America was estimated at 0.483 ± 0.060 SE (DeSante and Kaschube 2009). Adult survival rates in long-term studies in Europe using mark-recapture analyses include 0.343 ± 0.028 SE for males and 0.338 ± 0.047 SE for females in a declining population in Denmark (Møller and Szép 2002), 0.404 ± 0.028 (all adults) in Britain (Robinson et al. 2008) and about 0.48 in Switzerland (Schaub and Hirschheydt 2008).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Good information regarding the distribution, abundance and populations trends of Barn Swallows breeding in Ontario is available from the Breeding Bird Survey (Environment Canada 2013) and the first and second Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas projects (Cadman et al. 1987, Cadman et al. 2007).

Distribution

The Barn Swallow is one of the most widespread swallow species, breeding in temperate regions across the Northern Hemisphere (North America, Europe and Asia) and wintering primarily in Central and South America, southern Africa and southern and southeast Asia (Turner 2004). In North America this species breeds from southern Alaska east to southern Newfoundland and south through the United States and into central Mexico (Brown and Brown 1999a).

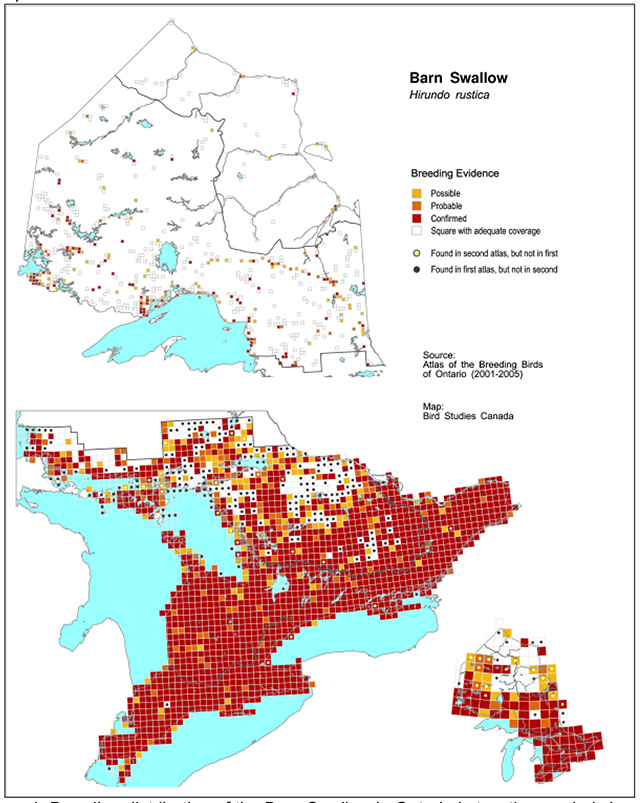

The current Barn Swallow breeding distribution is closely tied to that of the human population. It occurs throughout southern Ontario primarily south of the Canadian Shield (Figure 1). During the first and second Ontario Breeding Bird Atlases conducted during 1981 to 1985 and 2001 to 2005 respectively, the Barn Swallow was observed in nearly 100 percent of squares south of the Canadian Shield (Clark and Clark 1987, Lepage 2007). Although the Barn Swallow breeds as far north as the coast of Hudson Bay its distribution in northern Ontario is localized. The species is largely absent from remote sections of the far north, where no roads or human settlements exist.

The non-breeding range of the North American race of Barn Swallow extends from Mexico southwards throughout Central and South America (Howell and Webb 1995). The distribution of the Ontario breeding population within this very large non-breeding range is unknown.

Historical distribution

Prior to European settlement, the North American breeding distribution of this species was presumably restricted to areas with suitable natural nest sites particularly coastal and mountainous areas (Brown and Brown 1999a). There is a record of Barn Swallow nesting on longhouses (in British Columbia) dating back to the early 1800s (Macoun and Macoun 1904), and various sources have conjectured that Barn Swallows probably also nested in First Nations settlements in eastern North America (e.g., COSEWIC 2011).

Barn Swallows readily adapted to nesting on barns, bridges and other structures built by European settlers (Bent 1942). In addition the widespread clearing of forested lands for farming created suitable foraging habitat. Consequently, Barn Swallows have expanded their range into areas of North America where they did not occur formerly (Brown and Brown 1999a). This range expansion continued throughout the 20th century, most recently in the southeast United States where the population continues to increase (Robbins et al. 1986, Brown and Brown 1999a, Sauer et al. 2012).

In Ontario, the Barn Swallow has been reported since records were first kept (COSSARO 2011). This species was well established across southern Ontario prior to 1900 and was also reported as far north as the Hudson Bay coast (McIlwraith 1886, Macoun and Macoun 1904). Its distribution continued to expand in northern Ontario in the first half of the 20th century as it was able to colonize new settlements and infrastructure (Clark and Clark 1987, Lepage 2007).

Abundance

The Barn Swallow is the most abundant swallow species worldwide with a global population of some 120 million birds including 33 million birds in North America of which about 5 million breed in Canada (Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013). The population estimates for North America are derived largely from the Breeding Bird Survey data from 1998 to 2007 (Blancher et al. 2013). The global population estimate is extrapolated from the North American estimate based on the relative proportion of the global range (Blancher et al. 2013).

The Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas estimated the Ontario Barn Swallow population at 400,000 individuals during 2001 to 2005 (Blancher and Couturier 2007). This estimate is based on more than 50,000 point counts with good spatial coverage across the province and is therefore more representative than estimates based on Breeding Bird Survey data (Blancher and Couturier 2007, P. Blancher, pers. comm. 2013).

The Ontario population represents approximately one percent of the global population, and three percent of the North American population (Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013).

Factoring in the ongoing decline since the Breeding Bird Atlas estimate, the Ontario Barn Swallow population as of 2011 was estimated as less than 350,000 individuals (COSSARO 2011). During the post-breeding period the population is augmented by young-of-the-year (estimated 50% increase to approximately 500,000 individuals).

Caution is needed in interpreting and using these population estimates as the Breeding Bird Atlas estimates were "rough ballpark figures only" and "likely to be conservative" (Blancher and Couturier 2007, p. 655). These estimates should be considered approximations within an order of magnitude (P. Blancher, pers. comm. 2013).

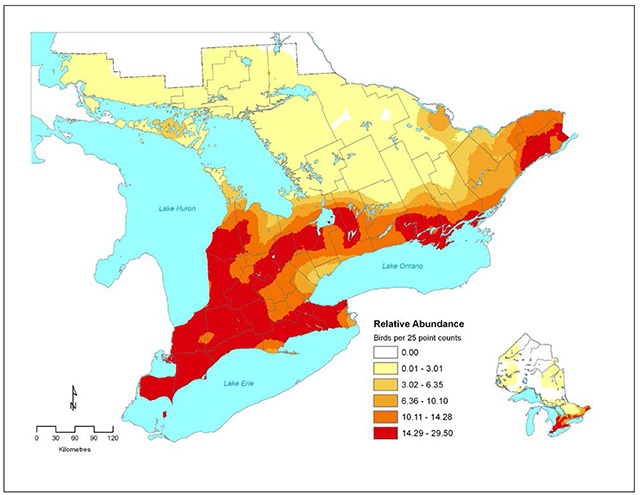

The atlas data showed that 91 percent of the Ontario population was concentrated south of the Canadian Shield,in the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Plain ecoregion (Cadman et al. 2007). Within this region the areas with the highest densities of Barn Swallows are: Stormont-Dundas-Glengarry County in the east, the northeastern shore of Lake Ontario, the southern part of Kawartha Lakes District and nearly all of southwestern Ontario (Figure 2).

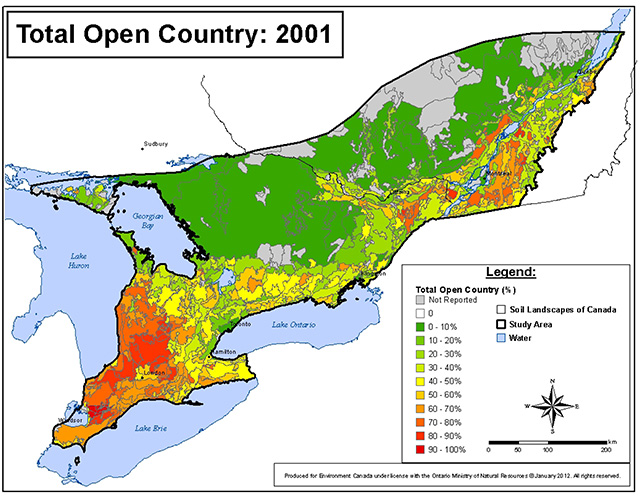

These high density areas all have relatively high amounts of open country habitat (Figure 3). However, there is no obvious relationship between Barn Swallow abundance patterns and the distribution of particular open country land cover types such as pasture (see Figure 11 in Neave and Baldwin 2011, S. Richmond pers comm. 2013).

Figure 1. Breeding distribution of the Barn Swallow in Ontario in two time periods based on Breeding Bird Atlas data (see Cadman et al. 2007) Coloured squares indicate reported distribution during 2001-05. Black dots depict distributional losses, squares where Barn Swallow breeding evidence was recorded during 1981-1985, but not during 2001-2005

Enlarge Figure 1 - Breeding distribution of the Barn Swallow in Ontario

Figure 2. Relative abundance of the Barn Swallow in southern Ontario based on Breeding Bird Atlas point count data collected in 2001-2005 (Cadman et al. 2007). See inset map for abundance in northern Ontario. County boundaries are depicted for southern Ontario

Enlarge Figure 2 - Relative abundance map

Figure 3. Total area in open country land cover classes (cropland, pasture and summer fallow) in southern Ontario during 2001 based on data from Statistics Canada (Neave and Baldwin 2011). Map courtesy of Graham Bryan, Environment Canada

Enlarge Figure 3 - Total area map

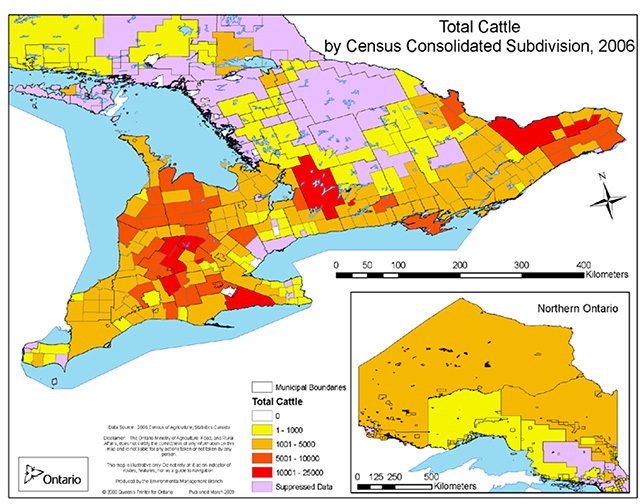

In Europe agricultural land use, particularly livestock farming, has been shown to be a strong influence on the distribution of Barn Swallows (Møller 2001, Ambrosini et al. 2002, Evans et al. 2007, Ambrosini et al. 2011a, Ambrosini et al. 2012). There is a general spatial correlation between Barn Swallow abundance and cattle densities in southern Ontario but the pattern is not consistent (Figure 4), with some areas of high Barn Swallow abundance having few cattle (e.g., Essex County) and vice versa (e.g., Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton).

Figure 4. Abundance of cattle (dairy and beef combined) in municipal boundaries of Ontario during 2006. Map is courtesy of Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food (P. Smith, pers. comm. 2012) based on data from Statistics Canada 2006 Census of Agriculture

Enlarge Figure 4 -Abundance of cattle

Population trends

Historically Barn Swallow populations were likely limited by the availability of natural nest sites (Holroyd 1975, Erskine 1979, Brown and Brown 1999a). Populations in heavily forested regions were also constrained by the availability of open country habitats for foraging.

Numbers of Barn Swallows in Ontario and other parts of North America undoubtedly increased following the arrival of European settlers due to the large increase in available anthropogenic nesting sites (Brown and Brown 1999a, COSEWIC 2011). However, in many settled areas populations may have peaked a century ago as agricultural modernization has generally resulted in conditions that are less favourable for this species (Bent 1942).

Good population trend data are available for much of Ontario and North America for the past four decades through the North American Breeding Bird Survey and Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas projects (Cadman et al. 1987, Cadman et al. 2007, Environment Canada 2013).

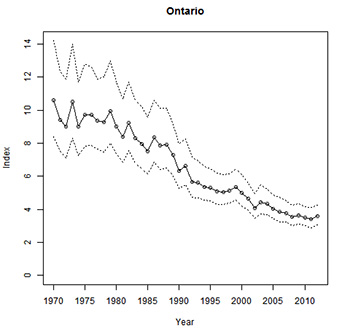

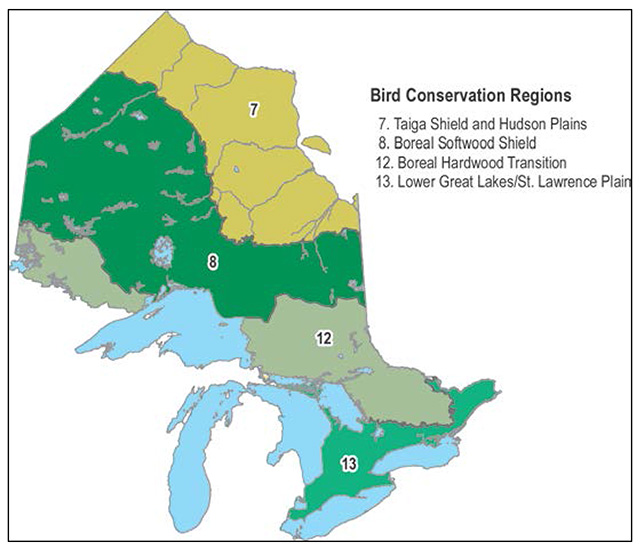

From 1970 to 2012, the Barn Swallow population in Canada declined by 80 percent (-3.74% annually) according to Breeding Bird Survey data (Table 1; Environment Canada in prep.). In Ontario, the annual rate of decline over this period is estimated at 2.56 percent, amounting to a cumulative loss of 66 percent (see Figure 5 and Table 1; Environment Canada 2013). Barn Swallow populations declined over this period in all regions of Ontario for which data are available (Table 1), with steeper declines in the Ontario portion of Bird Conservation Region (BCR) 12 (see Figure 6, equivalent to the southern Canadian Shield region) compared to the Ontario portion of BCR 13 (Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Plain region).

The probability of observation of Barn Swallows in Ontario declined significantly between the first (1981-1985) and second (2001-2005) Breeding Bird Atlas periods (-35% overall; Lepage 2007). On a regional scale, the probability of observation declined the most in the northern and southern Canadian Shield regions by 51 percent and 32 percent respectively. The probability of observation declined by seven percent in the Lake Simcoe-Rideau region but no change was detected in the Carolinian region where Barn Swallows continued to be reported as breeding in almost every square. No significant change was detected in the Hudson Bay Lowlands region where the species is very localized.

Breeding Bird Survey data for the most recent ten-year period, 2002 to 2012, indicate that Barn Swallow populations in Canada and Ontario have continued to decline but the average annual rate of decline has lessened to 2.56 percent (statistically significant) and 1.31 percent (near significant) respectively (Table 1). While the short-term rate of decline has abated at the national and provincial scales, the pattern of population change within Ontario is not consistent. The population trend for the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence (Ontario BCR 13) region from 2002 to 2012 was -0.084 percent annually (95% credible limits of -1.94 and 1.89), suggesting that the population in this region may have stabilized over the short-term. Barn Swallows in the Southern Shield region (Ontario BCR 12) continued to experience severe declines averaging -4.68 percent annually from 2002 to 2012. While not statistically significant, the short-term population trend for the Northern Shield (Ontario BCR 8) suggests that Barn Swallows may still be declining in this region (77.6% probablity of decline, Table 1).

Breeding Bird Survey data for the North American Barn Swallow population shows a small but significant long-term decline of -1.2 percent per year (95% CI -1.4, -1.0) over the 1996-2011 period (Sauer et al. 2012). Over the past 10 years (2001-2011) the North American population has been stable (0.0, 95% CI -0.4, +0.4) with population increases in parts of the United States breeding range offsetting ongoing declines in the Canadian population (Sauer et al. 2012).

European Barn Swallow populations show a somewhat similar pattern. Moderate declines were reported for Europe from 1970-1990 and also 1990-2000 (BirdLife International 2004), but the most recent data from 21 European Union countries indicate the European population has stabilized and even recovered to a level similar to 1980 (European Bird Census Council 2012).

Table 1: Long and short-term estimates of population change for the Barn Swallow in Ontario and Canada based on Breeding Bird Survey data using Hierarchical Bayesian trend modeling (Environment Canada in prep.). Boldface denotes significant trends. Ontario trends are also sub-divided into Bird Conservation Regions (BCR) (see Figure 6).

| Geographic Area | Time Period | Start Year-End Year | Annual Trend (%) | Lower Limits (95%) | Upper Limits (95%) | n (routes during trend years) | Trend Reliability | Probability of Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | short-term | 2002-2012 | -1.31 | -2.93 | 0.363 | 130 | Medium | 0.939 |

| Ontario | long-term | 1970-2012 | -2.56 | -3.17 | -1.97 | 152 | Medium | 1 |

| Ontario-BCR13 | short-term | 2002-2012 | -0.084 | -1.94 | 1.89 | 62 | Medium | 0.536 |

| Ontario-BCR13 | long-term | 1970-2012 | -1.2 | -1.79 | -0.577 | 68 | Medium | 1 |

| Ontario-BCR12 | short-term | 2002-2012 | -4.68 | -7.84 | -1.42 | 55 | Medium | 0.997 |

| Ontario-BCR12 | long-term | 1970-2012 | -4.73 | -5.63 | -3.79 | 66 | Medium | 1 |

| Ontario-BCR8 | short-term | 2002-2012 | -2.68 | -9.8 | 6.91 | 13 | Low | 0.776 |

| Ontario-BCR8 | long-term | 1970-2012 | -3.37 | -5.91 | -1.05 | 18 | Low | 0.998 |

| Canada | short-term | 2002-2012 | -1.85 | -2.84 | -0.747 | 631 | Medium | 0.998 |

| Canada | long-term | 1970-2012 | -3.74 | -4.15 | -3.34 | 754 | Medium | 1 |

Figure 5. Long-term population indices for Barn Swallows in Ontario during 1970-2012 based on Breeding Bird Survey data. Dotted lines depict 95 percent lower and upper credible intervals (Environment Canada in prep.).

Figure 6. Bird Conservation Regions in Ontario. Map courtesy Andrew Couturier, Bird Studies Canada.

Enlarge figure 6 bird conservation regions in Ontario map

1.4 Habitat needs

Barn Swallow habitat needs include foraging habitat, nest sites and nests and nocturnal roost sites. Daily access to suitable foraging areas with a reliable supply of insect prey is necessary throughout their life cycle. For breeding they require a suitable nest site in proximity to foraging habitat. Outside of the nesting period they require suitable habitat for roosting at night.

Foraging habitat

Barn Swallows forage over a wide range of open and semi-open habitats including natural and anthropogenic grasslands, other farmland, open wetlands, open water, savannah, tundra, highways and other cleared right-of-ways, and cities and towns (Brown and Brown 1999a). They avoid forested regions and high mountains.

Foraging is concentrated in areas with high availability of flying insects close to the ground or water surface. Insect-rich habitats vary seasonally and even daily. Frequently used foraging habitats include farmyards and grazed pastures, marshes and sloughs and coastal wetlands (Samuel 1971, Turner 1980, Godfrey 1986, Brown and Brown 1999a, Petit et al. 1999, Evans et al. 2007). In Europe grazed pastures and other grasslands are the preferred foraging habitat of this species during the breeding season, as they support high insect abundances and are proximal to nest sites (Møller 2001, Ambrosini et al. 2002, Evans et al. 2007, Grüebler et al. 2010).

Foraging habitats used in Ontario include farmland, lakeshore and riparian habitats, road right-of-ways, clearings in wooded areas, parkland, urban and rural residential areas, wetlands and tundra (Peck and James 1987). This species is largely absent as a breeding species in forested and muskeg-covered areas in Ontario (Peck and James 1987).

As noted earlier, the breeding distribution of this species in Ontario is correlated with open country habitat and over 90 percent of the population breeds in southern Ontario, where agricultural lands are the predominant open country habitat (Lepage 2007, Neave and Baldwin 2011). Grazed pasture and other agricultural grasslands are likely important foraging habitat for nesting Barn Swallows in Ontario as in Europe but Barn Swallows are also frequently observed foraging over cropland in Ontario (Boutin et al. 1999).

Information on Barn Swallow foraging distances is limited, particularly for North America, as very few studies of radio-tracked birds are available. Foraging distances vary seasonally. During non-breeding periods most foraging occurs within a 50 km radius of roost sites (Turner 2006). During the breeding season, particularly during the energy-intensive nestling rearing period, most foraging activity takes place as close to the nest site as possible (Turner 2006).

Samuel (1971) reported Barn Swallows "typically" foraged within 0.75 miles (1.2 km) and "seldom" foraged more than 0.5 miles (800 m) from the nest but this information appears to be based on one marked pair observed over a one week period in West Virginia and anecdotal observations. Several intensive observational foraging studies at European Barn Swallow colonies at farms found that almost all foraging occurs within 500 m of the nest site, with most trips within a 200 m radius (Turner 1980, Bryant and Turner 1982, Møller 2001, Ambrosini et al. 2002, Turner 2006). Foraging distance of nesting Barn Swallows in non-farm settings (e.g., Zduniak et al. 2011) has not been reported. Longer foraging distances around nests have been reported for other swallow species, particularly during periods of low insect abundance (Turner 1980, Ghilain and Bélisle 2008).

Nest sites and nests

Barn Swallows throughout the world have adapted to nesting in or on human structures, including buildings, barns, bridges, culverts, wells and mine shafts (Turner 2004). Use of natural nest sites such as caves or rock cliffs with crevices or ledges protected by overhangs is rarely reported (Erskine 1979, Speich et al. 1986, Brown and Brown 1999a). Recent efforts in Canada and the United States to construct stand-alone structures specifically to provide Barn Swallow nest sites have had varying success (Bird Studies Canada 2013, van Vleck 2013).

Nest sites in Ontario are commonly inside or outside of buildings, under bridges and wharves, and in road culverts (Peck and James 1987). Only 79 of 4279 (2%) Barn Swallow nests reported for Ontario were in natural settings (Peck and James 1987), although this sample may not be representative of the actual distribution of nests.

Nests are usually two to five metres above the ground or water surface and are usually constructed on a horizontal ledge or attached to a vertical wall close to an overhang (Turner 2004, COSEWIC 2011). Installation of artificial nest supports and cups to encourage Barn Swallow nesting has been tried in different situations with varying success (Turner 2006, Mercadonte and Stanback 2011, Bird Studies Canada 2013, van Vleck 2013). Mercadonte and Stanback (2011) reported that annual occupancy of 57 nest cups placed under a pier in North Carolina ranged from 23 to 46 percent over a five-year period (natural nests had been removed). Three of 56 artificial nest cups installed by Bird Studies Canada on existing structures with nesting Barn Swallows in southern Ontario were occupied in 2013 (Richardson 2013).

Nesting Barn Swallows must have access to suitable open habitat for foraging close to the nest and generally also require access to mud for nest building, although some nests in caves contain no mud (Peck and James 1987, Brown and Brown 1999a).

Unlike most small passerine nests, Barn Swallow nests persist for many years and are frequently re-used within a breeding season and in subsequent years. Barn Swallows that reuse nests have up to 25 percent higher reproductive success compared with those that construct new nests in some locations (Safran 2004, 2006) but not in others (Barclay 1988). Used nests are also an important habitat feature as a cue for yearling females selecting an initial nest site (Safran 2004, 2007).

Roosting habitat

Nocturnal roosts are typically in reed or cane beds or other dense vegetation, usually in or near water (Turner 2004, Winkler 2006). Post-breeding and migratory roost sites in Ontario are often associated with marshes or shrub thickets in or near water [e.g., willow thicket in London, Ontario (Saunders 1898 in Bent 1942); cattail marsh at Cataraqui Creek (Weir 2008); willow thicket on a small (0.2 ha) island in Pembroke, (Ross et al. 1984); marshes at base of Long Point peninsula (D. Bell, pers. comm. 2012); marsh at Pumpkin Point near Sault Ste. Marie (D. Bell, pers. comm. 2012)].

Little information is available on winter roost habitat for the North American subspecies but it includes sugarcane fields, reed beds and marshes (Vannini 1994, Basili and Temple 1999, Brown and Brown 1999a, Petit et al. 1999). Winter roosts elsewhere are also typically in reed beds, sugarcane fields or standing corn fields in rural settings (Turner 2004). In some parts of Asia however Barn Swallows roost on overhead cables, building ledges and trees in urban settings (Ewins et al. 1991).

1.5 Limiting factors

Biological attributes that affect the feasibility of recovery approaches for this species include:

- relatively short life span (maximum of 10 years, average age in breeding population estimated at 3-4 years);

- relatively high reproductive potential (often double brooded, capable of producing 10 young per year);

- high fidelity of adults to previous breeding sites and the low fidelity of yearlings to their natal sites;

- vulnerability to extended bouts of adverse weather or other events that limit the availability of flying insects;

- vulnerability to localized hazards (e.g., severe weather events during migration, predation or persecution at roost sites, aerial spraying of pesticides on foraging flocks) due to its gregarious behaviour during the non-breeding period

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Numerous factors have been proposed as possible explanations of the recent declines in Barn Swallows and other aerial insectivores in Canada (Nebel et al. 2010, COSEWIC 2011, Calvert 2012). However, the information needed to critically evaluate the past, present and future impacts of these potential threats to Barn Swallows in Ontario is generally lacking (COSSARO 2011). Key knowledge gaps that must be addressed in order to assess the severity and magnitude of the many possible threats that affect the survival and recovery of this species are identified in section 1.7.

Barn Swallows breeding in Ontario are affected by the cumulative impact of stresses experienced on their breeding grounds, during the post-breeding dispersal period, during spring and fall migration and while wintering in South or Central America. Factors affecting individual fitness can result in carry-over effects from one season to the next.

This species' close association with human-modified open country habitats (most notably agricultural lands) throughout most of its life cycle makes it especially sensitive to changes in land use and other human activities. Threats affecting the Barn Swallow’s food supply (flying insects) may also be implicated in declines observed in many other species of aerial insectivore.

Given the known and potential threats to this species, it is unclear why the pattern of long-term declines is confined largely to northern Barn Swallow populations, whereas southern populations in the United States are stable or increasing.

This summary of human-caused threats mostly focuses on threats occurring in Ontario during the breeding and post-breeding periods because: (1) reproductive success is a key demographic factor for this short-lived species, (2) very little is currently known about the nature, extent and severity of threats affecting Barn Swallows during the migration and wintering periods when they are outside of Ontario, and (3) the focus of this recovery strategy is to identify key practical actions that the Ontario government could undertake to promote the recovery of Barn Swallow.

This long-distance migrant spends much of the year outside of Ontario and implementing recovery actions only in Ontario may not be sufficient to recover the population. While the recovery of Barn Swallow in Ontario will ultimately depend on reducing significant threats affecting the species' survival wherever they are occurring, recovery actions to maintain or enhance the productivity of birds in Ontario should increase the probability of success.

The following assessment of the known and potential threats to Ontario Barn Swallows is based on the best information currently available including expert opinion gathered during the development of this recovery strategy. It seems likely that multiple direct and indirect threats are having an additive or synergistic impact on Barn Swallow populations as the known threats do not appear to adequately explain the observed population decline (COSEWIC 2011, COSSARO 2011). The significance and severity of these threats should be continually reassessed as new information becomes available.

Threats are presented in order of certainty, extent and anticipated importance to the Ontario recovery strategy as their relative severity is not known at this time.

Loss of nest site habitat

Loss of Barn Swallow nest sites due to demolition, replacement or renovation of human structures is a widespread and ongoing threat. In particular, replacement of old wooden farm buildings with modern structures that do not provide accessible nest sites is often cited as a principal reason for Barn Swallow population declines in Canada (see COSEWIC 2011). The supply of nest sites on other human structures (e.g., bridges, culverts, wharves, boathouses, residential and commercial buildings) may also be reduced as old structures are replaced with modern designs or retro-fitted in a manner that birds can no longer access nest sites.

Food safety regulations require that birds be excluded from food processing facilities, including milking parlors and vegetable packing areas. In addition there are numerous bird exclusion products available on the market although the extent to which they are being installed to deter Barn Swallows from nesting is unknown.

Changes in construction materials and designs can also affect the suitability of nest sites by changing thermal conditions (e.g., increased heat-induced mortality of nestlings in metal-roofed barns, Tate 1986) or by affecting (decrease or increase) the accessibility of nests to predators and nest competitors.

There has been no net change in the availability of natural nest site habitat (COSEWIC 2011).

While there is high certainty that the availability of barns and other human structures that provide nest sites has decreased over the past several decades and will continue to decrease, the significance of this threat to the recovery of the species is less clear (COSEWIC 2011, COSSARO 2011).

Nest site availability and the severity and the magnitude (frequency and extent) of nest site loss in Ontario have not been quantified. Numerous anecdotal reports of former nest sites (including anthropogenic sites and natural cliff sites) that are currently unoccupied suggest that additional factors are contributing to the recent population decline (COSEWIC 2011, COSSARO 2011).

Given the high nest site fidelity of this species, the permanent or temporary loss of a previous nest site is likely detrimental to the annual reproductive success of returning individuals. Birds can show strong attachment to a particular nest site. Considerable effort is required to prevent Barn Swallows from nesting (e.g., where repair work is planned or in nuisance locations). The impact of the reduction in available nest sites on yearling recruitment rates is not known, and presumably varies depending on the availability of other nest sites nearby.

Loss or degradation of foraging habitat

Threats to Barn Swallow foraging habitat in Ontario include changes in land cover and land use that result in the loss or degradation of insect-rich habitats within open country habitat. The quantity and quality of foraging areas in close proximity to nest sites, near roost sites and along migratory routes are important habitat parameters. In Ontario, changes in agricultural land use are particularly important as agriculture is the dominant land cover in the open country habitats where this species is most abundant (Neave and Baldwin 2011).

The amount and nature of open country habitat in southern Ontario (including the Southern Shield ecoregion, see Figure 3) has undergone dramatic changes over the past 200 years (Neave and Baldwin 2011). Open country habitats in southern Ontario prior to European settlement included local areas of native grassland, savannah, alvar and rock barrens, and First Nations agricultural lands (Neave and Baldwin 2011). In the 19th century the amount of open country habitat in southern Ontario increased as forested lands were cleared for agriculture (Neave and Baldwin 2011). Over the past century, open country habitat in southern Ontario decreased substantially due to reforestation of marginal farmland (especially in the Southern Shield ecoregion) and urbanization (Blancher et al. 2007, Neave and Baldwin 2011). Since 1971, there has been little change in the total amount of open country habitat in southern Ontario (Neave and Baldwin 2011).

While the amount of open country habitat in southern Ontario may have stabilized in recent years, there continues to be major changes to land cover due to changes in agricultural land use that could be affecting Barn Swallows and other wildlife populations (Javorek et al. 2007, Neave and Baldwin 2011). Steady declines in the total amount of farmland in Ontario and the amount of pasture since 1921 have continued through 2011 (Javorek et al. 2007; Statistics Canada 2007, 2012). In contrast, the total amount of cropland (including tame hay) in Ontario has remained quite stable over this period (Statistics Canada 2007, 2012). Recently, there has been a shift from hay in favour of annual row crops with the proportion of cropland in hay dropping from 28 percent to 23 percent between 2006 and 2011 (P. Smith, pers. comm. 2012, Statistics Canada 2012). Changes in agricultural land use are driven by socio-economic factors. Changing dietary preferences, changing farm practices and recent high corn and soybean prices have resulted in a general shift from dairy and cattle farming to intensive annual field crop production in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence region (Latendresse et al. 2008, Jobin et al. 2010).

In some parts of southern Ontario, rural non-farm properties with horses and pasture are increasingly common. Information on land use on these lands is not reported in the agricultural statistics as they are not considered census farms.

Changes in agricultural practices and land use that affect flying insect populations can have a major impact on this species. A study in Britain found aerial insect abundance and Barn Swallow density varied by crop type, with highest numbers over pasture and lowest numbers over row crops (Evans et al. 2007). In Europe, there is a strong link between Barn Swallow population size, distribution and productivity and the presence of livestock and pasturelands (Møller 2001, Robinson et al. 2003, Grüeebler et al. 2010, Ambrosini et al. 2011a, Ambrosini et al. 2012). A landscape-scale study in Quebec found a negative relationship between Tree Swallow breeding success and agricultural intensification (Ghilain and Bélisle 2008).

Ongoing trends that may be adversely affecting Barn Swallow foraging habitat in agricultural settings in Ontario include:

- continuing reduction in cattle herds;

- continuing reduction in pasturing of dairy cows and other livestock;

- improved sanitation practices (manure and fly management) on livestock farms;

- continuing loss of pasture;

- conversion of hayfields to annual row crops;

- increased field size and reduction in hedgerows resulting in lower insect abundance and diversity;

- changes in the types of pesticides (especially insecticides) in use; and

- increased planting of genetically-modified, insect-resistant row crop

Other insect-rich habitats that are preferred Barn Swallow foraging areas are associated with natural grasslands, wetlands, riparian habitats and water bodies. Changes in the extent and quality of these foraging habitats could be affecting food availability at various times in the Barn Swallow life cycle.

Changes in food supply are suspected as being an important factor in the decline of Barn Swallows and other aerial foraging insectivores (Nebel et al. 2010). It is uncertain as to where in the life cycle of these migratory species these changes are occurring (e.g. on wintering grounds, migration routes or breeding grounds), or whether they are related to changes in foraging habitat or other factors such as environmental pollution or climate change (see below).

Environmental contaminants, pesticides and pollution

Environmental contaminants, pesticides and pollutants that may directly or indirectly affect the survival and reproductive output of Barn Swallows (and other aerial insectivores) include:

- poisoning or sub-lethal harmful effects caused by exposure to pesticides, heavy metals, endocrine disrupters or other pollutants;

- large-scale calcium depletion (affects reproduction) due to acid precipitation;

- pesticides (particularly insecticides) impacting food supply; and

- light pollution around urban and built-up areas that may reduce local food supplie

The Barn Swallow’s close association with human-altered habitats throughout its life cycle suggests it may be at an elevated risk from pesticides and pollution. As Barn Swallows frequently forage over agricultural fields in southern Ontario they face relatively high levels of exposure to pesticides although their exposure risk is lower than ground foraging birds (Boutin et al. 1999). Although pesticide use is lower in agricultural grasslands (hay and pasture) than in other crops, a recent study found that lethal risk from insecticide exposure was the best predictor of declines in grassland birds in the United States (Mineau and Whiteside 2013). The indirect impacts of pesticides and pollution on food supply or quality is likely a more significant potential threat than direct poisoning at least on the breeding grounds in Ontario.

The quantity of agricultural pesticides applied in Ontario has declined in recent decades, with a 45 percent reduction in overall agricultural pesticide use between 1983 and 2008, and a 76 percent reduction in agricultural insecticide use in this period (McGee et al. 2010). A provincial ban on the cosmetic use of pesticides was implemented in 2009. There have however, been significant shifts in the types of pesticides being used in Ontario over time. Recently there has been considerable concern as to potential biological impacts of neonicotinoid insecticides, a new class of insecticide that was first used in Canada in the 1990s and is now widely used in Ontario and elsewhere. Neonicotinoids are systemic insecticides that act as insect neurotoxins. They have been implicated in the decline of honeybee colonies and other insect pollinators in Europe and North America and to global wildlife declines (Mason et al. 2013). There is growing evidence that these insecticides could be impacting bird populations due to direct toxicity and also as a result of the indirect impact of an overall reduction in insect biomass (Mineau and Palmer 2013).

Reduced productivity due to predation, parasitism and persecution

Predation, parasitism and persecution are known threats that can cause severe reductions in local productivity and other adverse effects. The extent and frequency of these threats has not been quantified. In general there is no indication that these threats have increased over time.

Various non-native and native predators commonly associated with human habitations may reduce productivity by predating eggs, nestlings, fledglings and/or adult Barn Swallows. Species that have been identified as particular problems include cats, rats, mice, raccoons, grackles, falcons, hawks and owls (Turner 2006, COSEWIC 2011, Salvadori et al. 2011).

Interspecific competition for nest sites with non-native House Sparrows and native Cliff Swallows can also result in reduced productivity (COSEWIC 2011, Salvadori et al. 2011). Rock Pigeons may also displace Barn Swallows at some nest sites (M.Taylor, pers.comm. 2013). House Sparrows also affect productivity directly by killing eggs and nestlings.

Barn Swallows are affected by many parasites including blood-sucking mites and lice, and internal parasites (Turner 2006). Elevated levels of ectoparasites can cause high nestling mortality and can also have carryover effects on the fitness of surviving young (COSEWIC 2011, Saino et al. 2012).

Barn Swallow nests in or on buildings are sometimes deliberately destroyed by people because the accumulation of droppings below nests is seen as a potential health hazard. Active nests may also be removed or otherwise disrupted if they are considered a nuisance because the swallows mob intruders near their nests or because of aesthetic or noise concerns. Temporary or permanent measures may be implemented to discourage birds from re-nesting at these sites (e.g., the use of predators was proposed at a marina in Toronto; Alamenciak 2012). Disturbance to active nests may severely affect local populations but the extent and severity of this threat is not known.

Landowner attitudes towards Barn Swallows likely vary considerably depending on the specific situation and degree of inconvenience. Studies of landowner attitudes at farms in the Netherlands found that Barn Swallows nesting in locations where they were not wanted was not a major issue and the species was viewed as a beneficial insectivorous species rather than as a pest (Lubbe and de Snoo 2007, Kragten et al. 2009). Barn Swallows in Sweden tested negative for salmonella (Haemig et al. 2008), casting doubt on whether their faeces constitute a significant health concern.

The removal of used nests (e.g., for cosmetic reasons or for routine maintenance activities) at any time of the year may pose a threat to the recovery of the species for two reasons. In some situations there appears to be a small reproductive advantage to reusing a nest compared to building a new nest (Safran 2004, 2006 but see Barclay 1988). Second, the removal of used nests negatively affects colony size during the following breeding season as yearling females cue in on the presence of used nests when selecting a nest site (Safran 2004, 2007).

Habitat loss, disturbance and human persecution at roost sites

Habitat destruction or degradation due to activities that disturb roosting birds and land uses that attract predators are known threats at roost sites. Adjacent development as well as predation by an increasing Merlin population may have been factors in the abandonment of the summer swallow roost in downtown Pembroke, Ontario in the 1990s (Ottawa River Legacy Landmark Partners 2013). The significance of threats to roost sites is unknown as information on the locations and size of Barn Swallow roost sites in Ontario and elsewhere is very limited.

Winter roosts in Central and South America may be subject to additional specific threats including poisoning or disturbance of roost sites due to measures taken to control other avian pest species (e.g., Dickcissel) (Basilli and Temple 1999), or even direct exploitation as a food source as reported at winter roosts in parts of Asia and Africa (Ewins et al. 1991, Turner 2004).

Climate change and severe weather

Barn Swallows are vulnerable to severe weather events that exceed their temperature tolerances (e.g., cold snaps, heat-induced mortality of nestlings) or reduce the supply of flying insects (e.g., prolonged cold weather or drought) (Turner 1980, Nebel et al. 2010, Møller 2011). Severe weather events during migration can result in mass mortality of Barn Swallows (e.g., 40% reduction in Barn Swallow populations across a large area of Europe following an extreme snowfall event in the Alps in fall 1974, Møller 2011). While these events are normally infrequent (Møller 1978, Newton 2007, Brown and Brown 1999b, Møller 2011), climate change may be increasing the frequency of hurricanes and other severe weather events (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2007).

Climate change may be affecting Barn Swallows populations in various ways including changing the timing of migration, their breeding and wintering distributions, the condition of arriving birds and vital rates (Turner 2009). These effects can be positive or negative and may vary by geographic region (Balbontín et al. 2009b, Turner 2009, COSEWIC 2011, Shutler et al. 2012).

Advances in European Barn Swallow migration dates and a northward shift in their wintering distribution can extend the breeding season and increase seasonal productivity (Møller 2008, Balbontín et al. 2009b, Ambrosini et al. 2011b). However,

hotter, drier weather can reduce insect populations and adversely affect productivity and survival (Balbontín et al. 2009b, Saino et al. 2004, Saino et al. 2011). A rapidly changing climate can also lead to a temporal mismatch between food availability and energy requirements for Barn Swallows and other aerial insectivores (Ambrosini et al. 2011b, Saino et al. 2011, Calvert 2012). Various European studies have found that survival and productivity rates are correlated with climatic factors that affect insect populations on the breeding and wintering grounds (Møller 1989, Møller and Szép 2002, Saino et al. 2004, Robinson et al. 2008, COSEWIC 2011).

Climate change effects on North American Barn Swallow populations remain largely speculative but are likely to be mixed as has been reported for Tree Swallows in North America (Dunn and Winkler 1999, Hussell 2003, Shutler et al. 2012).

1.7 Knowledge gaps

The Barn Swallow has been the focus of extensive studies particularly in Europe and Africa but much less is known about the ecology and conservation needs of the North American subspecies. The few published studies carried out at breeding colonies in Ontario have been limited in focus, geographic scope and duration (Holroyd 1975, Smith et al. 1991, Smith and Montgomerie 1991, Smith and Montgomerie 1992, Boutin et al. 1999, Salvadori 2009, Salvadori et al. 2011).

Fundamental uncertainties that are pertinent to the recovery of this species include:

- the demographic processes and proximate and ultimate factors driving recent declines in Barn Swallow and other aerial insectivores; and

- the extent and severity of current and potential threats in Ontario and elsewhere.

Uncertainty as to the threats and environmental factors limits our ability to determine what constitutes an achievable long-term recovery goal, prioritize recovery objectives, and predict the efficacy of various recovery approaches.

Several specific information deficiencies regarding Ontario Barn Swallow biology, habitat needs and threats were identified at the expert consultation workshop held in December 2012. These knowledge gaps were grouped into six themes: (1) vital rates, (2) diet and food supply, (3) habitat requirements and trends on the breeding grounds, (4) habitat and ecology during winter and on migration, (5) best management practices (BMPs), and (6) climate change effects. Research is currently underway to address some of these knowledge gaps (see section 1.7).

Vital rates and population source/sink dynamics

Information on the vital rates of the Ontario Barn Swallow population is needed to understand the demographic processes underlying the population decline and to identify where in the life cycle recovery action will be most effective. Comparable demographic data are also needed from other parts of the North American range including areas with population increases.

Specifically, systematic sampling is needed across the Ontario breeding range to assess:

- productivity;

- nestling growth rates under various conditions;

- adult return rates to previous nest sites and nests;

- recruitment of yearling birds to breeding locations; and

- survival rates of adults and young at each stage of the annual life cycle (breeding, post-breeding, and overwintering periods).

This information is needed to address key questions regarding population source/sink dynamics such as:

- demographic parameters correlated with nest substrate or colony size (e.g., is nest success affected by structure type); and

- what impact food shortages, nest competitors, predators, parasites and loss of used nests have on productivity.

Diet and food supply

Widespread declines in aerial insectivore populations has raised concern as to whether there have been large-scale changes in insect populations due to insecticides, environmental contaminants, habitat degradation, climate change or other factors.

Specific information needs are:

- Barn Swallow diet in Ontario and elsewhere in the life cycle;

- patterns of insect abundance and diversity among various habitat types;

- contaminant loads (e.g., neonicotinoids) in Barn Swallows and their food supply; and

- trends in insect abundance in Ontario and elsewhere that may be causing a bottleneck in the Barn Swallow’s life cycle.

Habitat use, habitat requirements and habitat trends in ontario

Specific information that is needed to evaluate the significance of habitat loss and degradation in Ontario as a factor in past declines and a threat to recovery are as follows.

- Nest sites and used nests

- What proportion of the Ontario Barn Swallow population uses various nest sites (barns, bridges/culverts, boathouses, natural cliffs e)?

- How is the availability of various types of nest site changing over time?

- What are the physical characteristics of nest sites?

- How severe an impact do nest competitors have on nest site availability?

- What is the extent and impact of deliberate and inadvertent nest site exclusion and nest destruction (of both active and used nests) in various settings?

- How important are used nests as a habitat feature in various settings in Ontario?

- Foraging habitat

- foraging distances around nest sites and roost sites;

- size, habitat type and quality (food availability) of foraging habitat close to nest sites;

- amount of foraging habitat required to sustain different colony sizes;

- relationships among foraging habitat, insect availability and Barn Swallow productivity;

- spatial correlations between Barn Swallow abundance and habitat features (including presence of livestock) at various scales (nest-to landscape-scale); and

- spatial and temporal correlations between Barn Swallow populations and changes in land use, agricultural practices, and pesticide us

- Roosting habitat

- Location and habitat features of major post-breeding roost sites in Ontari

Wintering and migration habitat and ecology