Bent Spike-rush Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the bent spike-rush, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

September 2010

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA, 2007, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA, 2007 outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA, 2007. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage at: www.ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Bowles, J. M. 2010. Recovery strategy for the Bent Spike-rush (Eleocharis geniculata) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 17 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2010

ISBN 978-1-4435-4000-1 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007, n'est disponible qu'en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Pamela Wesley au ministère des Richesses naturelles au 705-755-1661.

Authors

Jane M. Bowles, UWO Herbarium, University of Western Ontario

Acknowledgments

This Recovery Strategy was prepared under contract from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. The following people have helped with the development of the recovery strategy by providing help and information. Elizabeth Reimer, SAR Intern, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources; Michael Oldham, Botanist, Natural Heritage Information Center and Terry McIntosh, consulting botanist and senior author of the COSEWIC Status Report on Bent Spike-rush all provided information. Steve Matson, CalPhotos allowed the use of his photographs.

Declaration

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has led the development of this recovery strategy for the Bent Spike-rush in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario

Executive summary

Bent Spike-rush is a small (2-20 cm tall), annual, tufted plant that grows in open areas on the sheltered shorelines of ponds and lakes. The species is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007). There are two populations in Ontario. One population is on the shoreline of a dug sand pit in the hamlet of Cedar Springs, in the Municipality of Chatham-Kent. The second, and larger population, is found scattered along the shores of ponds and in shallow interdunal swales near the tip of Long Point, Norfolk County. The total population sizes are estimated at 300-500 at Cedar Springs and 1300 to 2500 at Long Point, although a comprehensive survey has not been carried out at either site. Since the plant is an annual the population of mature individuals likely fluctuates from year to year, and long-term survival of the species depends on dormant seeds stored in the substrate. Little is known about the longevity of the seeds or the size of the seed bank.

The main threat to the species is degradation of habitat as a result of invasion by the introduced and invasive variety of Common Reed (Phragmites australis), commonly referred to as Phragmites. This plant is actively invading many wetlands in southern Ontario and is present at both populations of Bent Spike-rush. Populations of Phragmites on Long Point increased from 18 ha to almost 140 ha between 1995 and 1999, and have increased about five-fold since then. Since Bent Spike-rush requires open strand lines to grow, competition from Phragmites and changes in shoreline dynamics are considered threats, especially where physical changes in the shoreline have been affected by the presence of Phragmites. At Cedar Springs, the population is in a habitat that is at least partly created by humans. The habitat of Bent Spike-rush is currently protected under the ESA, 2007.

The recovery goal for Bent Spike-rush is to prevent further loss of habitat within the area of occupancy at both sites where it occurs so that populations are maintained.

The objectives of this recovery strategy are:

- Inventory and map all known Bent Spike-rush locations, populations and habitats by 2015 to provide a quantitative baseline for future monitoring and initiate a monitoring program.

- Monitor populations and extent of Phragmites at Bent Spike-rush sites at regular intervals (at least every 2-3 years) on an on-going basis to provide data on the extent and rate of habitat change.

- Investigate options for removal and/or control of Phragmites at Bent Spike- rush sites that are most vulnerable to this threat. Prepare plans for Phragmites management and begin management by 2012.

- Research the habitat requirements (including hydrologic regime), population biology, dispersal and seed bank dynamics of Bent Spike-rush to determine feasibility of survival, relocation and recovery in protected habitat.

- Provide communication and outreach to landowners, municipalities and planners to restrict habitat destruction by development at the Cedar Springs site. Incorporate specific protection into the next draft of relevant municipal Official Plans.

Approaches to protection and recovery include detailed inventory and mapping of populations and habitats, including the extent of the threat of Phragmites. This will provide baseline data from which the success of recovery actions can be measured. Habitat recovery, restoration and rehabilitation may be achieved through management or removal of Phragmites. Opportunities for Phragmites control need to be investigated and experimental treatments carried out that can be the basis for adaptive management.

It is recommended that the habitat at Long Point be prescribed as habitat for Bent Spike-rush in a habitat regulation. This habitat includes those areas of the North Beach and the shorelines of interdunal ponds and wet meadows between Gravelly Bay and the tip of Long Point that are occasionally or seasonally inundated and that remain moist for most of the growing season, and where the native vegetation that competes with Bent Spike-rush is naturally sparse to open. At Cedar Springs, it is recommended that the graded shoreline of the sand pit be prescribed as habitat for Bent Spike-rush in a habitat regulation.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Bent Spike-rush

Scientific name: Eleocharis geniculata SARO List Classification: Endangered SARO List History: Endangered (2009)

COSEWIC Assessment History: Great Lakes Plains population – Endangered (2009) SARA Schedule: N/A

Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5 NRANK: NNR SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Bent Spike-rush is a small plant with densely tufted, green and slightly waxy-looking, threadlike stems 2-20 centimetres long and 0.2-0.5 millimetres in diameter. There are no underground stems (rhizomes). The base of the stem has two pale green sheaths that are often tinged reddish brown in lower part. A single, many-flowered spikelet about 3-7 millimetres long, 3-4 millimetres wide and rounded or slightly pointed is borne at the summit of the flowering stem. The scales of the spikelet are rusty or pale brown, broadly egg-shaped or elliptical, obtuse and about 1.5-2 millimetres long. Flowers are bisexual with both male and female parts. The fruit is a smooth black, glossy, achene about 1 millimetres long and broadly obovoid (egg-shaped, but widest at the top). The achene is surrounded by 6-7 soft, rust-coloured bristles with small barbs on them. The top of each achene is adorned with a wide, flattish, pale green structure known as a tubercle (Menapace 2002) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Achenes of Bent Spike-rush. CalPhotos Photo Database © 2003 Steve Matson. Used with permission.

Species biology

Bent Spike-rush is a pan-tropical wetland species that extends into temperate regions at the edge of its range and typically grows in sand or mud along the shoreline at the edge of lakes, ponds and rivers. It is also found in seeps, salt-marshes, rice paddies and taro fields in the tropics (Menapace 2002). In Ontario it is found on muddy or silty soils at the edge of ephemeral ponds, beaches and wet meadows that are flooded early in the year but later dry out. It appears in places where other vegetation is sparse or absent so that competition from other species is low. Plants mature and set seed in late summer and early autumn, usually around the first week of September in Ontario (COSEWIC 2009).

Plants grow each year from seed deposited the previous year or that are dormant in the seed bank. For annual species, such as Bent Spike-rush, long term persistence depends on seeds stored in the seed bank, with plants growing and setting seed only in years when the conditions are favourable. Dormancy may last for several to many years (COSEWIC 2009). Annual changes in water levels can have a large effect on the area of suitable habitat available from year to year (personal observation), and population sizes may fluctuate considerably (COSEWIC 2009). Population trends can only be established from regular monitoring over several years, but trends may be inferred from the extent of suitable habitat.

Bent Spike-rush has no obvious means of long distance dispersal. Seeds probably fall close to the parent plants or are washed off during rising water levels. Seeds float for a few hours when first released and may get washed along the shoreline. Movement of seeds in mud stuck to the feet of waterfowl was proposed as a mechanism of dispersal by Darwin (1859) and has been demonstrated for other species of Eleocharis (Bell 2000). The scattered distribution of Bent Spike-rush in Ontario, and its absence from some locations with apparently suitable habitat, suggests that dispersal is quite limited.

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

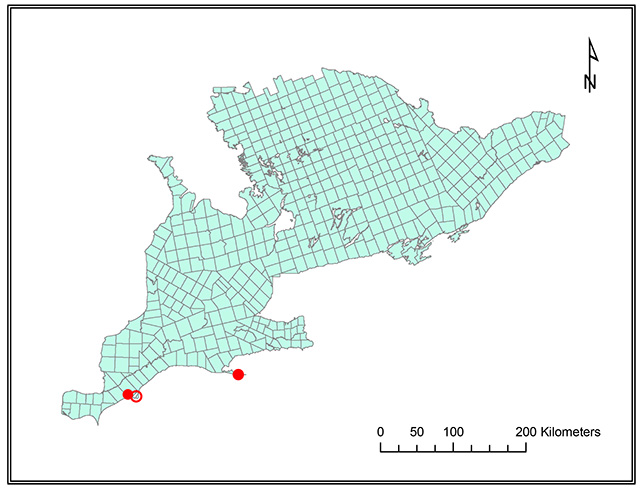

There are two known extant populations and one known historical population of Bent Spike-rush in Ontario. The first report of Bent Spike-rush in Canada was from Rondeau Provincial Park in 1934 (Taylor, 1935), but the plant has not been found there since despite several searches (COSEWIC 2009). At Long Point it was first observed in 1979 and was reported by Reznicek and Catling (1989) as being "occasional but widespread on beach strands and sandy pond shores between Gravelly Bay and the tip of the Point". Most stands are within the Long Point National Wildlife Area. The Cedar Springs site was discovered in 1996 by M.J. Oldham and A.W. Cusick (COSEWIC 2009). The Rondeau Provincial Park and Long Point sites are along the Lake Erie shoreline while the Cedar Springs location is about 2 kilometres inland on the shoreline of Glacial Lake Warren.

Targeted searches for Bent Spike-rush were conducted at all known Ontario sites in 2007 by T. McIntosh, M.J. Oldham, S. Brinker and A. Reznicek during field work for the COSEWIC Status Report (COSEWIC 2009). The number of mature, fruiting individuals was 300-500 plants at Cedar Springs and 1,000-2,000 at Long Point. At Long Point, stands of Bent Spike-rush were found scattered over an area about 4.4 kilometres long. Not all suitable habitat in the area was searched; abundance estimates were made visually on transects into previously known sites. Estimates of plant numbers were made at locations where GPS waypoints were recorded and inferred from the extent of suitable habitat.

The population at Cedar Springs was not surveyed quantitatively before 2007, but no obvious changes in density or abundance have been noted since it was discovered in 1996 (COSEWIC 2009).

Similarly, no earlier counts of Bent Spike-rush have been made at Long Point. In 2007 the species was absent from several places where it had been present in 1988 or earlier (M. J. Oldham pers. comm. 2009). In some places it was still present, but there seemed to be fewer plants than in previous years. Some sites with suitable habitat in 1988 had grown in with the invasive variety of Common Reed (Phragmites australis), commonly known as Phragmites.

Figure 2. Historical (open circle) and current distribution (closed circle) of Bent Spike-rush in Ontario

1.4 Habitat needs

Bent Spike-rush is limited in Ontario close to the shore of Lake Erie. The specific habitats for Bent Spike-rush are the sheltered shorelines of lakes and ponds on the strand lines at the water and on flat beaches where the water table is close to the surface. Bent Spike-rush usually grows in open areas where other shoreline species are present, but it cannot compete with tall or permanent vegetation such as Phragmites. On a local scale the habitat is usually quite ephemeral, moving back and forth across the shoreline in response to changes in water levels.

There are only two known extant locations for the species in Ontario. At the Cedar Springs location, Bent Spike-rush is found within the boundaries of the hamlet of Cedar Springs. It grows on a sloping shoreline at the edge of an old sand pit on an ancient beach ridge of a glacial lake, and is about 1.7 kilometres inland from the current lakeshore. Associated species include Elliptic Spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica), Northern Bugleweed (Lycopus uniflorus), Green Sedge (Carex viridula), Greater Canadian St. John’s-wort (Hypericum majus), Phragmites, Small-flowered Agalinis (Agalinis paupercula), Narrowleaf Paleseed (Leucospora multifida), Northern Green- rush (Juncus alpinoarticulatus ssp. nodulosus), Brook Flatsedge (Cyperus bipartitus) and Annual Witchgrass (Panicum capillare) (McIntosh 2007).

At Long Point, Bent Spike-rush grows along the sandy or silty shorelines of ponds in interdunal swales within 5 kilometres of the tip of the point. The area and depth of water in these ponds, and the width of the strand areas, are dependent on the water levels in the ponds. These in turn are related, at least partially, to the water level of Lake Erie, which typically fluctuates about 0.5 metres annually and up to 2 metres on longer-term cycles (NOAA 2009). Typical associated species in the habitat include Elliptic Spike- rush, Low Nutrush (Scleria verticillata), Green Sedge, Horned Beakrush (Rhynchospora capillacea) and Philadelphia Panic Grass (Panicum philadelphicum) in places where there is more than 99 percent bare substrate of silt and organic matter on sand.

Bent Spike-rush is also sometimes found on the open bottom of drying ponds with associates including Annual Witchgrass, Smooth Sawgrass (Cladium mariscoides), Marsh Arrowgrass (Triglochin palustre), Squarestem Spike-rush (Eleocharis quadrangulata), Green Sedge and Horned Bladderwort (Utricularia cornuta). It also occurs in a long, shallow interdunal depression near the south shore of Long Point, south of Gravelly Bay, often with Bright Green Spike-rush (Eleocharis olivacea), which stands out as being less common and larger; Slender Fimbry (Fimbristylis autumnalis), Green Sedge, Horned Beakrush, Smooth Sawgrass and Water Milfoil (Myriophyllum sp.) may also be present. This habitat has large patches of Phragmites invading the site (McIntosh 2007).

1.5 Limiting factors

The main limiting factor for Bent Spike-rush in Canada is the very specific habitat, with limited geographic distribution, in which it grows. Sheltered shoreline sites have limited distribution in Ontario and are subject to changes in water levels. In years of high water levels, beaches, strands and the shorelines of ponds may be very narrow because part, or even most, of the habitat is under water. There are clearly other (unknown) factors limiting the species because it has very limited occurrence even in habitats that are apparently suitable.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

The main threat to Bent Spike-rush in Ontario is invasion of the known sites and areas of suitable habitat by the invasive variety of Phragmites at both Long Point and Cedar Springs (COSEWIC 2009).

The amount of Phragmites is expanding rapidly into the shorelines of ponds where Bent Spike-rush grows. Wilcox et. al. (2003) showed that the area of Phragmites stands on Long Point expanded from 18 hectares in 1995 to 137 hectares in 1999. This exponential expansion is continuing. Data from Phragmites cover estimated in permanent vegetation monitoring plots show that in 2009 the amount of Phragmites was about 5 times greater than in 1999 (Bowles and Bradstreet unpublished data). Growth of Phragmites is known to respond to increased nitrogen in shoreline systems (Silliman and Bertness 2004). Increased nitrogen inputs at Bent Spike-rush habitats may come from agricultural runoff into rivers, and thus the lake, and from atmospheric deposition.

Because the shoreline habitat of Bent Spike-rush is dynamic in nature, changes in lake levels and shoreline dynamics may alter some sites (for example by sand accretion, erosion, flooding) so that they no longer provide suitable habitat. This is a natural and continuing process on Long Point (Reznicek and Catling 1989), but it may be exacerbated by changes in vegetation such as an increase in the population of Phragmites.

At Cedar Springs, there is an additional threat of possible residential development at the site. The site lies within the boundaries of the Hamlet of Cedar Springs in Raleigh Township. The Chatham-Kent Official Plan (2009) allows for residential development and growth within hamlet boundaries, but provides for the protection of significant habitat for endangered and threatened species and adjacent areas.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

The most important knowledge gaps for the recovery and protection of Bent Spike-rush in Ontario relate to the extent, size and precise locations of the Long Point population. Observations have been made over the last few decades by knowledgeable individuals familiar with the species, but information from a detailed survey is lacking. The extent of the species in apparently suitable habitats is not known. Some previous locations have been altered by changes in lake level and beach dynamics, and the species may have disappeared from some sites. Invasion by Phragmites is altering the structure and composition of plant communities, including some globally imperilled vegetation types such as the Great Lakes Coastal Meadow Marsh, as well as altering physical and chemical properties of the habitats (Rudrappa et al. 2007). Changes in the population levels and in the extent and quality of habitat for Bent Spike-rush can only be monitored and tracked effectively if baseline levels are known for all known sites. The long-term fate of the habitat (and presumably the species) can only be projected and predicted if the habitats and their dynamics are understood. Another important gap is the response of the species to management of the habitat through control of Phragmites, and whether this is even feasible.

Little is known about the year-to-year fluctuations in the populations of Bent Spike-rush and how, and what, environmental factors affect germination, population numbers and fruiting success. Almost nothing is known about seed dispersal or seed dormancy and seed bank characteristics such as size, longevity and turnover. As an annual species, continued existence of the plant from one year to the next relies entirely on seeds.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

To date there have been no recovery actions specific to Bent Spike-rush in Ontario. Surveys by McIntosh, Oldham, Reznicek and Brinker (COSEWIC 2009) have begun to document threats and the decline of Bent Spike-rush in Ontario. The studies showing the increasing threat of Phragmites (Wilcox et al.2003, Bowles and Bradstreet unpublished data) are not specific to Bent Spike-rush habitat.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal for Bent Spike-rush is to prevent further loss of habitat within the area of occupancy at both populations where it occurs so that populations are maintained.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

The protection and recovery objectives are listed in order of priority in Table 1 below. Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Inventory and map all known Bent Spike-rush locations, populations and habitats by 2015 to provide a quantitative baseline for future monitoring and initiate a monitoring program. |

| 2 | Monitor populations and extent of Phragmites at Bent Spike-rush sites at regular intervals (at least every 2-3 years) on an on-going basis to provide data on the extent and rate of habitat change. |

| 3 | Investigate options for removal and/or control of Phragmites at Bent Spike-rush sites that are most vulnerable to this threat. Prepare plans for Phragmites management and begin management by 2012. |

| 4 | Research the habitat requirements (including hydrologic regime), population biology, dispersal and seed bank dynamics of Bent Spike-rush to determine feasibility of survival, relocation and recovery in protected habitat. |

| 5 | Provide communication and outreach to landowners, municipalities and planners to restrict habitat destruction by development at Cedar Springs site. Incorporate specific protection into the next draft of relevant municipal Official Plans. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

The recommended approaches to recovery are listed in Table 2. Short-term and immediate critical actions are inventory and accurate mapping of the populations of the Bent Spike-rush, their habitat, and the populations of Phragmites that threaten the habitat. Controlling Phragmites using an adaptive approach that responds to current wisdom and monitoring the results of on-going trials are necessary long-term actions.

Table 2. Approaches to recovery of the Bent Spike-rush in Ontario

1. Inventory and map all known Bent Spike-rush locations, populations and habitats by 2015 to provide a quantitative baseline for future monitoring and initiate a monitoring program

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 1.1 Conduct detailed mapping and census of known populations

|

|

| Critical | On-going | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 1.2 Repeat mapping, census and measurements of all known populations (as above) to assess species dynamics over an extended period (10 years) |

|

2. Monitor populations and extent of Phragmites at Bent Spike-rush sites at regular intervals (at least every 2-3 years) on an on-going basis to provide data on the extent and rate of habitat change

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Monitoring and Assessment; Research | 2.1 Create detailed maps of extent of Phragmites stands at Bent Spike-rush locations

|

|

3. Investigate options for removal and/or control of Phragmites at Bent Spike-rush sites that are most vulnerable to this threat. Prepare plans for Phragmites management and begin management by 2012

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing | Management | 3.1 Investigate Phragmites management options from literature, current practices and knowledgeable individuals.

|

|

| Critical | Long-term | Management |

3.2 Design and execute experimental management of Phragmites in selected plots

|

|

4. Research the habitat requirements (including hydrologic regime), population biology, dispersal and seed bank dynamics of Bent Spike-rush to determine feasibility of survival, relocation and recovery in protected habitat

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | Ongoing and long-term | Research | 4.1 Establish research protocols to investigate reproductive and habitat biology of Bent Spike- rush.

|

|

5. Provide communication and outreach to landowners, municipalities and planners to restrict habitat destruction by development at Cedar Springs site. Incorporate specific protection into the next draft of relevant municipal Official Plans

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | Short-term | Communications and Stewardship | 5.1 Communicate with decision makers at Cedar Springs population.

|

|

2.4 Performance Measures

Table 3. Performance measures

| Protection or Recovery Objective | Performance Measures |

|---|---|

| Objective 1: Inventory and map all known Bent Spike-rush locations, populations and habitats by 2015 to provide a quantitative baseline for future monitoring and initiate a monitoring program. |

|

| Objective 2: Monitor populations and extent of Phragmites at Bent Spike-rush sites at regular intervals (at least every 2-3 years) on an on-going basis to provide data on the extent and rate of habitat change. |

|

| Objective 3: Investigate options for removal and/or control of Phragmites at Bent Spike-rush sites that are most vulnerable to this threat. Prepare plans for Phragmites management and begin management by 2012. |

|

| Objective 4: Research the habitat requirements (including hydrologic regime), population biology, dispersal and seed bank dynamics of Bent Spike- rush to determine feasibility of survival, relocation and recovery in protected habitat. |

|

| Objective 5: Provide communication and outreach to landowners, municipalities and planners to restrict habitat destruction by development at Cedar Springs site. Incorporate specific protection into the next draft of relevant municipal Official Plans. |

|

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, 2007, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Bent Spike-rush is an annual species with, presumably, fluctuating populations of mature plants. It grows in a narrow range of specific habitat that may move from year to year in response to fluctuating water levels. The extent of the specific habitat may vary depending on year-to-year changes in water level, the physical properties of the systems such as slope of the land, deposition of sand during storm events and the amount of competition from other plants.

It is recommended that at Long Point, the areas of the North Beach and the shorelines of interdunal ponds and wet meadows between Gravelly Bay and the tip of Long Point be prescribed as habitat for Bent Spike-rush in a habitat regulation. This should only include those areas that are inundated seasonally or by fluctuating lake levels and that remain moist for most of the growing season, and where the native vegetation that competes with Bent Spike-rush is naturally sparse to open. Specific sites may expand, contract and move according to lake levels and changes in dune dynamics. There is a high probability that additional stands of Bent Spike-rush may be found through this area since populations of Bent Spike-rush fluctuate, the species is relatively inconspicuous, and detailed botanical surveys have not been done in all locations. It is also recommended that accurate inventory and mapping of these habitats on Long Point be conducted to support the habitat regulation.

At Cedar Springs, Bent Spike-rush grows in a habitat that is formed by human activity. The species is found on the graded shoreline of a pond formed in a dug sand pit. It is recommended that the graded shoreline of the sand pit be prescribed as habitat for Bent Spike-rush in a habitat regulation.

Glossary

Achene: A small dry (non-fleshy) fruit containing a single seed.

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

NR = the conservation status is "not ranked" or assessed yet in that jurisdiction

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

GPS (Global Positioning System): A navigational or locating system that involves satellites and that can determine the exact location (latitude and longitude) of a receiver on the ground by calculating the time difference of signals that reach the receiver from different satellites.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

Strand line: The zone at the top of a beach or shoreline that marks the high water level. Stranded debris and litter often accumulate along the strand line.

References

Bell, D.M. 2000. Dispersal of Eleocharis seeds by birds. The Australian Society for Limnology Conference. Darwin N.T.

Chatham-Kent Official Plan (2009). Turning Vision into Reality. Municipality of Chatham Kent, Civic Centre, Chatham Ontario. 53 pp.

COSEWIC 2009. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Bent Spike-rush Eleocharis geniculata, Great Lake Plains population and Southern Mountain population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa vii + 30 pp.

Darwin, C. 1859. On the Origin of Species by means of natural selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. John Murray. London. 490 pp.

Menapace, F.J. 2002. Eleocharis R. Brown (subg. Eleocharis sect. Eleogenus) ser. Maculosae. Pp. 100-102 in: Flora of North America Volume 23, Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Cyperaceae. Oxford University Press, New York.

McIntosh, T. 2007. Ontario notes re Eleocharis geniculata search, September 2007. Personal communication to M.J. Oldham, September 2007. 3 pp + photographs.

NOAA 2009. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Great Lake Environmental Research Laboratory. Water Level Plots – Lake Erie.

Oldham, M.J. 2009. Personal Communication. E-mail correspondence with Jane Bowles, November 2009.

Reznicek, A.A. and P.M. Catling. 1989. Flora of Long Point, Regional Municipality of Haldimand-Norfolk, Ontario. Michigan Botanist 28(3): 99-175.

Rudrappa, T, J. Bonsall, J. L. Gallagher, D.M. Seliskar & H.P. Bais. 2007. Root- secreted Allelochemical in the Noxious Weed Phragmites australis Deploys a Reactive Oxygen Species Response and Microtubule Assembly Disruption to Execute Rhizotoxicity. Journal of Chemical Ecology 33: 1898–1918.

Silliman, B.R. and M.D. Bertness 2004. Shoreline Development Drives Invasion of Phragmites australis and the Loss of Plant Diversity on New England Salt Marshes. Conservation Biology, 18(5): 1424–1434.

Taylor, T.M.C. 1935. Eleocharis caribaea var. dispar in Ontario. Rhodora 37: 365-366.

Wilcox, K.L., S.A. Petrie, L.A. Maynard, and S.W. Meyer. 2003. Historical distribution and abundance of Phragmites australis at Long Point, Lake Erie, Ontario. Journal of Great Lakes Research 29(4): 664-680.