Blue Racer Recovery Strategy

This document is the recovery strategy for a species at risk – the Blue Racer.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There was a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy.

The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Willson, R.J. and G.M. Cunnington. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 35 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2015

ISBN 978-1-4606-3080-8 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Michelle Collins au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Author

Robert J. Willson

RiverStone Environmental Solutions Inc.

Glenn M. Cunnington

RiverStone Environmental Solutions Inc.

Acknowledgments

This recovery strategy is based on earlier drafts prepared by Paul Prevett, James Kamstra, Ben Porchuk and Carrie MacKinnon. The following recovery team members provided input to the previous draft recovery strategy prepared by Carrie MacKinnon, and R. Willson has discussed details of the Blue Racer on Pelee Island with them many times in the past: Ben Porchuk, Ronald Brooks, Carrie MacKinnon, Allen Woodliffe, Dawn Burke, James Kamstra, Tom Mason, Robert Murphy and Robert Zappalorti. The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry provided the financial support to complete this recovery strategy.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Blue Racer was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

Formerly found in extreme southwestern Ontario, the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) is a snake that is now confined to Pelee Island. The Blue Racer is listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) declared the Blue Racer endangered in 1991 and this status was retained in status updates in 2002 and 2012. The Blue Racer is also identified as endangered under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

The Blue Racer is one of Ontario’s largest snakes. Relative to the other snake species that occur on Pelee Island the Blue Racer is uncommon. The primary threats to survival and recovery of the species on Pelee Island are habitat loss and degradation, vehicular mortality and intentional persecution.

The recovery goal for the Blue Racer in Ontario is (1) to maintain, or if necessary increase population abundance to ensure long-term population persistence; (2) increase habitat quantity, quality and connectivity on Pelee Island; and (3) continue to assess the feasibility of repatriating the species to portions of its former range on the southern Ontario mainland. The protection or recovery objectives are as follows.

- Protect habitat and connections, and where possible, increase the quantity and quality of available habitat for Blue Racer on Pelee Island.

- Promote protection of the species and its habitat through legislation, policies, stewardship initiatives and land use plans.

- Reduce mortality by minimizing threats.

- Address knowledge gaps and monitor Blue Racer population.

- Continue to assess the feasibility of repatriating Blue Racers to a location on the southern Ontario mainland.

The three most important types of habitat for the Blue Racer, in order of importance, are (1) hibernation habitats, (2) nesting habitats and (3) shelter habitats. Although these three habitats are the most important for maintaining a viable population, other habitats used for foraging, mating and movement are necessary for population persistence. All of these types of habitat are necessary for individuals of the species to complete their life cycle and thus should be prescribed in a habitat regulation for Blue Racer.

Given the importance and sensitivity to disturbance of hibernation and nesting habitats, it is recommended that these features be recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration. Additionally, shelter habitats that are used by two or more Blue Racers (i.e., are communal) should be recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration. Blue Racers show fidelity to all of these types of habitat, particularly areas used for hibernation.

Additional recommendations pertaining to hibernation habitat to be considered in a habitat regulation are as follows.

- Hibernation habitat should be protected until it is demonstrated that the feature can no longer function in this capacity.

- The area within 120 m of an identified hibernation feature (single site or complex) should be regulated as habitat and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration.

Additional recommendations pertaining to nesting and shelter habitat to be considered in a habitat regulation are as follows.

- A naturally occurring nesting habitat or communal shelter habitat (i.e. used by two or more Blue Racers) that has been used at any time in the previous three years should be protected.

- A non-naturally occurring nesting habitat or communal shelter habitat (i.e. used by two or more Blue Racers) should be protected from the time its use was documented until the following November 30.

- The area within 30 m of the boundary of the nesting feature should be regulated as habitat and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration.

Foraging and mating habitats should be recognized as having a moderate sensitivity to alteration. Relative to hibernation, nesting and shelter habitats, the spatial extent of foraging, mating and movement habitats is considerably larger. Foraging and mating habitats are best defined at the level of ecological community (e.g. savanna, woodland) and these areas will be several hectares in size.

It is recommended that the following ecological community types on Pelee Island be regulated as foraging and mating habitats when they occur within 2,300 m of a reliable Blue Racer observation:

- alvars (treed, shrub and open types);

- thicket;

- savanna;

- woodland; and

- edge (includes hedgerows and riparian vegetation strips bordering canals).

It is evident that there are not well-defined movement corridors for Blue Racer. Given the considerable spatial extent of the areas that would be regulated as hibernation, nesting, shelter, foraging and mating habitat as per the recommendations above, it is recommended that no additional areas be regulated as movement habitat.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

- Common name: Blue Racer

- Scientific name: Coluber constrictor foxii

- SARO List Classification: Endangered

- SARO List History: Endangered (2004)

- COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2012, 2002, 1991)

- SARA Schedule 1: Endangered (January 12, 2005)

- Conservation status rankings:

- GRANK: G5

- NRANK: N1

- SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

The Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) is one of Ontario’s largest snakes, reaching lengths of 90 cm to 152 cm snout-to-vent length (SVL; Conant and Collins 1998). The largest documented specimen captured on Pelee Island was 138 cm SVL (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data). Blue Racers often have creamy white ventral scales, dull grey to brilliant blue lateral scales and pale brown to dark grey dorsums (Porchuk 1996). They also have characteristic black masks, relatively large eyes and often have brownish- orange rostral scales (snouts). Unlike adults, hatchlings and yearlings (first full active season) have dorsal blotches that fade completely by the third year; however, juvenile patterning is still visible on the ventral scales until late in the snake’s third season (Porchuk unpub. data).

Species biology

The Blue Racer is an egg-laying snake and average clutch size on Pelee Island for seven females was 14.7 ± 2.53 (standard deviation; Porchuk 1996). Females can reproduce annually (Rosen 1991, Carfagno and Weatherhead 2006), but biennial cycles have also been documented (Porchuk 1996). Males can mature physiologically at 11 months (Rosen 1991) but do not have the opportunity to mate until their second full year. Similarly, females may mature at 24 months (Rosen 1991) but are not able to reproduce until the following year (Porchuk 1996). On Pelee Island, mating occurs in May. Females lay eggs in late June through early July and eggs hatch from mid-August to late-Septemberember (Porchuk 1996).

Blue Racers hibernate underground for five to seven months each year (Porchuk 1996, Brooks et al. 2000, Willson 2002). Most adult Blue Racers hibernate communally and occasionally hibernacula are shared with Eastern Foxsnake (Pantherophis gloydi), Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) and Eastern Gartersnake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis) (Porchuk 1996). Monitoring of known communal hibernacula on Pelee Island suggests that individual Blue Racers do not begin to use the communal sites where adults hibernate until their third year (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data).

Blue Racers are active during the day and are active foragers (Fitch 1963). Adults engage in both terrestrial and arboreal foraging (Porchuk 1996). Young snakes may consume crickets and other insects, whereas adults feed primarily on rodents, birds and snakes (Fitch 1963, Ernst and Ernst 2003, Porchuk 1996, Porchuk unpub. data).

Probable natural predators of adult Blue Racers on Pelee Island include the larger birds of prey (e.g. Red-tailed Hawk, Buteo jamaicensis; Northern Harrier, Circus cyaneus; Great-horned Owl, Bubo virginianus) and mammals such as Raccoon (Procyon lotor), Foxes (Vulpes vulpes and Urocyon cinereoargenteus), and Coyote (Canis latrans) (COSEWIC 2002, Ernst and Ernst 2003). Dogs (Canis familiaris) and feral house cats (Felis cattus) are known to kill and/or harass juvenile Blue Racers (COSEWIC 2002) and it is likely that adult Blue Racers are also occasionally killed by these animals given that even large, venomous snakes are preyed upon regularly by cats (see Whitaker and Shine 2000). The eggs and young are likely vulnerable to a wider variety of avian and mammalian predators. Wild Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) were re-introduced to Pelee Island in the winter of 2002 and as an opportunistic feeder, may prey upon juvenile Blue Racers (MacKinnon 2005).

Blue Racers seem to be relatively intolerant of high levels of human activity, and for most of the active season they remain in areas of low human density (Porchuk 1996). Evidence to substantiate this comes largely from radiotelemetry data from both Blue Racers (Porchuk 1996) and Eastern Foxsnakes (Willson 2000a) that inhabited the same general areas on Pelee Island (although studies were not conducted concurrently). For instance, Eastern Foxsnakes were often found under front porches, in barns/garages and in the foundations of houses, whereas most Blue Racers were observed in areas with less human activity (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data).

Similar to other active foraging snakes studied (e.g. Rouse et al. 2011), Blue Racers on Pelee Island were documented to move substantial distances over the active season (Porchuk 1996). Twenty-two female Blue Racers moved an average of 241.3 ± 14.5 (standard error) metres per day when they were documented moving on a particular day (on many days snakes do not move) and 12 male Blue Racers moved an average of 250.3 ± 18.5 (standard error) metres per day when they were documented moving on a particular day (Porchuk 1996).

The hibernaculum is crucial to the survival of snakes inhabiting temperate latitudes (Prior and Weatherhead 1996) and Blue Racers show a high degree of fidelity to these sites (Porchuk 1996). Therefore, distance-based metrics that incorporate the hibernaculum will be the measures of spatial dispersion most relevant to conservation efforts (COSEWIC 2008, Rouse et al. 2011). Maximum Distance found from Hibernacula (MDH) values calculated for 25 Blue Racers (14 females; 11 males) radiotracked by Porchuk (1996) are as follows: mean MDH = 1,391.6 ± 616.63 (standard deviation) m, median MDH = 1,145.0 m, 90 percent quantile = 2,276.8 m, range = 467.0–2,714.0 m (Willson and Porchuk unpub. data).

Distances from hibernacula to other important habitats such as nest sites also have high conservation value. The maximum straight-line distance between a female’s hibernaculum and nest site documented by Porchuk (1996) was 2,600 m.

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Distribution

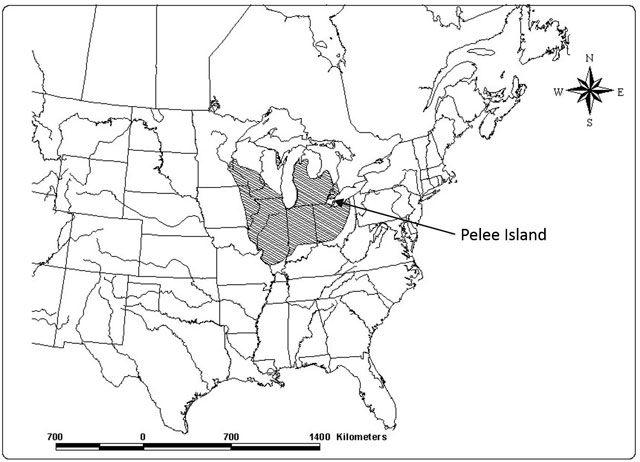

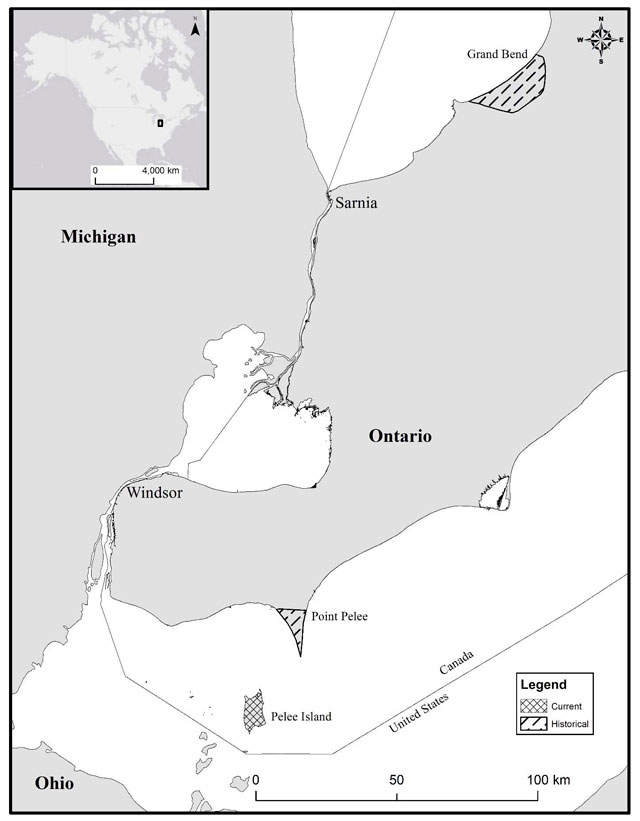

The historical distribution of the Blue Racer in North America ranges from extreme southwestern Ontario to central and southern Michigan, northeastern Ohio, eastern Iowa, southeastern Minnesota and to southern Illinois (Conant and Collins 1998; Figure 1). Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa are the only states with extant populations of Blue Racer (Harding 1997). In Canada, Blue Racers are now found only on Pelee Island (Figure 2). The most reliable historical records of Blue Racer on the Ontario mainland are from Point Pelee National Park (Essex County) and the Grand Bend/Pinery Provincial Park area (Lambton and Huron Counties). The last possible but unconfirmed report of a Blue Racer from the Ontario mainland was along the Ausable River in 1983 (Kamstra 1991). In the early 1990s, searches and appeals were extended for information or sightings in the vicinity of Pinery Provincial Park; however, no sightings were reported. See Rowell (2012) for a thorough summary of historical Blue Racer records from the Ontario mainland.

Abundance and population trends

To estimate the size of the Pelee Island Blue Racer population, a three-year mark- recapture and radiotelemetry study was conducted from 1993 to 1995. The resultant mark-recapture data were incorporated into a Jolly-Seber population model and generated a population size estimate of 307 adults (95% confidence interval = 129–659; Porchuk 1996) for 1994. Further mark-recapture sampling of the Pelee Island Blue Racer population was conducted over the three-year period 2000 to 2002 (Willson 2002). Over the three years of the survey, 1,584 person hours were spent searching four study sites.

In total, 222 Blue Racers were encountered, of which 166 were captured (75% capture rate). The persistence of Blue Racers within three focal areas identified in earlier studies was confirmed and the species continued to be absent from a fourth historically- inhabited site. The number of Blue Racers encountered at each study site differed substantially and corroborated site-specific abundance levels documented in earlier studies.

Jolly Seber mark-recapture analyses generated a population size estimate for the three study sites combined of 140.7 ± 73.47 (95% confidence interval = 59.0–284.7) adult Blue Racers (Willson 2002). Comparisons between the population estimates generated from the two study periods (1993–1995 and 2000–2002) are not possible because the earlier study’s sampling methodology was less systematic (e.g. sampling effort was not restricted to quantifiable locations or times) and the most recent survey was geographically restricted to specific properties (Willson 2002). Because of the systematic design of the most recent survey, comparisons with future sampling periods should be possible.

As of 2005, six Blue Racers had been located outside of the area of occupancy shown in COSEWIC (2002) and two of these individuals were hatchlings (Willson and Porchuk unpub. data). Three of the six Blue Racer observations (1997, 2004) were at the Red Cedar Savanna south of East-West Road and just east of the Pelee Island Winery Pavilion. These observations indicate that the area is used by Blue Racers, at least during the late summer when adults often disperse large distances from their hibernacula (Porchuk 1996). It is also possible, however, that some of these individuals are using hibernation sites west of the area of occupancy that have yet to be documented.

1.4 Habitat needs

At a landscape scale, Blue Racers on Pelee Island predominantly use dry, open to semi-open areas (i.e., minimal canopy closure), as well as the edges of these and other ecological community types such as woodlands and forests (Porchuk 1996). The preference for edge habitat documented for this species by Porchuk (1996) was also observed by Carfagno and Weatherhead (2006) in Illinois. Additionally, both Porchuk (1996) and Carfagno and Weatherhead (2006) documented a preference of racers for early to mid-successional vegetation communities (i.e., areas with low to intermediate canopy closure). Porchuk (1996) defined edge as occurring within five metres of the interface between the two adjoining communities (e.g. forest-woodland, marsh-thicket). For example, where a forest transitions to a farm field, the edge habitat would extend five metres into the forest and five metres into the farm field. Hedgerows and the majority of the riparian vegetation strips bordering canals were considered edge under this definition.

On Pelee Island, the ecological communities that are open or semi-open and correspond with the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) of Lee et al. (1998) are as follows: alvar, thicket, savanna and woodland (when tree cover is at the lower end of the range for this community). It should be recognized that the habitat classifications and descriptions used in Porchuk (1996) predated the ELC for southern Ontario and thus the habitat descriptions more closely align with those of Kamstra et al. (1995). Additionally, areas recognized as high quality habitat for snakes are not always easily described by the ELC (Willson unpub. data).

For the majority of snakes inhabiting temperate-zone climates, thermoregulation is an important driver of habitat selection (e.g. Blouin-Demers and Weatherhead 2001). As such it is not surprising that Blue Racers on Pelee Island used habitats with less canopy closure in the spring than during the summer when they also were documented in areas with higher canopy closure (e.g. woodlands and forests; Porchuk 1996). Similar shifts in habitat use were also documented for racers (Coluber constrictor) in Illinois (Carfagno and Weatherhead 2006). In addition to being documented in forests during the summer, Blue Racers likely also move through forests to reach preferred habitats (Porchuk 1996). Indeed, given the limited spatial extent of forest communities (> 60% tree cover) on Pelee Island, and the high movement capacity and tendency of Blue Racers documented by Porchuk (1996), it is unlikely that there are any forested areas on the island that individual Blue Racers could not move through (Willson unpub. data).

For egg-laying snakes inhabiting northern latitudes, the three most important types of habitat in order of importance are (1) hibernation habitats, (2) nesting (egg-laying) habitats and (3) shelter habitats (e.g. features that facilitate ecdysis (shedding or moulting of skin), digestion and protection from predators) (COSEWIC 2008). Although these three habitats are the most important for maintaining a viable population, other habitats used for foraging, mating and movement are also necessary for population persistence.

Hibernation habitat

On Pelee Island, several hibernation complexes are located within the limestone plain regions (Porchuk 1996). Within these limestone plains there are areas where cracks and fissures in the bedrock provide access to underground cavities or caverns. Blue Racers enter these cavities in the fall and emerge in the spring (Porchuk 1998). Radiotelemetry and mark-recapture data showed that while underground in many of these hibernation areas, snakes could move several metres horizontally; thus, many of the cracks visible on the surface are connected underground (Porchuk 1996). Some of the hibernation complexes approach 120 m in diameter (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data). In addition to the hibernation areas in the bedrock, Blue Racers have also been documented hibernating in piles or accumulations of rock and soil (Porchuk 1996). Blue Racers exhibited high fidelity to hibernation habitats (Porchuk 1996).

Nesting habitat

Eggs are laid in fallen decaying logs, under large rocks and in mounds of decaying organic matter (Porchuk and Brooks 1995, Porchuk 1996). Eggs are also laid under discarded pieces of sheet metal, boards and other human refuse. However, the majority of the eggs laid under these objects do not hatch (Porchuk 1996, Porchuk 1998). The majority of nests are located in areas exposed to sunlight most of the day (i.e., high exposure to solar radiation because of limited canopy cover; Porchuk 1996). Intra- and interspecific (with Eastern Foxsnake) communal nesting has been documented on Pelee Island (Porchuk and Brooks 1995, Porchuk 1996).

Shelter habitat

This type of habitat is used by Blue Racers during periods when they need to maintain their body temperature within a preferred range for several days while being protected from predators. For example, snakes shed or moult their skin up to four times per year. During this process (ecdysis), which on average lasts 5 to 10 days under natural conditions, individual snakes usually become sedentary (R. Willson, unpub. data). Becoming sedentary and seeking shelter habitat during this period is driven both by the need to maintain preferred body temperatures (higher body temperatures accelerate body processes) and to reduce the risk of predation during the phase of the ecdysis when vision is impaired. Additionally, this type of habitat is used when a snake is digesting recently ingested prey (larger prey items requiring longer periods). Other situations when Blue Racers may use a shelter habitat include after an injury and females may use preferred sites at some stage of gestation prior to nesting. While using this type of habitat, Blue Racers may be visible during certain times of the day (i.e., basking) or, depending on the time of year and the ambient temperatures, they may be hidden the majority of the time (Porchuk 1996).

Shelter habitat is typically composed of living or dead vegetation on the ground or in trees, large flat rocks, piles or accumulations of rock and soil, discarded sheet metal and car parts (Porchuk 1996, Willson 2002). These features can be naturally occurring or established by human activity. Similar to hibernation and nesting habitats, Blue Racers exhibit fidelity to shelter habitat (e.g. some rocks and brush piles are used repeatedly by individuals over a single active season or over the course of several years) (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data). Additionally, the majority of shelter habitats are located in areas exposed to sunlight most of the day (i.e. high exposure to solar radiation because of limited canopy cover; Porchuk 1996; Porchuk and Willson unpub. data).

Foraging, mating and movement habitat

These types of habitat are less sensitive to disturbance than the hibernation, nesting and shelter habitats, and they are more difficult to define and delineate. Nevertheless, Blue Racers require access to suitable foraging and mating habitat to complete important life processes. Foraging and mating activities occur most often, although not exclusively, in alvar, thicket, savanna, woodland and edge communities (Porchuk 1996, Brooks and Porchuk 1997). For example, Porchuk (1996) observed 50 percent (14 of 28) of courtships and the lone copulation on the edges of fields, canals, hedgerows and roads and 28.5 percent (8 of 28) of courtships in savanna and open field.

Ensuring connectivity between the different types of habitat is essential to maintaining a viable Blue Racer population on Pelee Island. When the space use of the Blue Racer population is examined as a whole and over the entire active season, it is evident that there are not well-defined movement corridors. For example, although most individual Blue Racers tend to follow hedgerows between vegetated patches, individual snakes were documented moving through fields with crops (e.g. soybean winter wheat and corn; Porchuk 1996). Currently there are no absolute barriers to movement.

1.5 Limiting factors

Population size and distribution

Relative to the other snake species that occur on Pelee Island, the Blue Racer is uncommon. The size of the Pelee Island Blue Racer population may render it vulnerable to extinction from demographic and environmental stochasticity, catastrophic events and loss of genetic variability (Caughley 1994, Burkey 1995). Isolated from other Blue Racer populations, there can be no effective immigration of individuals to Pelee Island or emigration of individuals to other island or mainland sites (i.e., a natural range expansion beyond the island’s boundaries is highly unlikely; Porchuk 1998).

Availability of hibernation habitat

Brooks and Porchuk (1997) suggest that the lack of appropriate hibernation habitat is likely one of the major factors limiting the distribution of Blue Racers on Pelee Island. Similar to other Ontario snake species that have been examined to date (Prior et al. 2001, Lawson 2005, Rouse 2006), Blue Racers exhibit high fidelity to specific hibernation sites and consequently would have difficulty finding a new hibernaculum if these habitats are destroyed.

Availability of nesting habitat

The reproductive success of Pelee Island Blue Racers may be limited by the availability of suitable nesting habitat. Female Blue Racers favour decaying logs as nesting sites (Porchuk 1996), which on Pelee Island are often restricted to shoreline areas. Because of the specific physical characteristics of these sites (i.e., narrow range of temperature and moisture levels, protection from predators), they are naturally rare. As shoreline habitat becomes increasingly altered for human use, these sites will become more limited and females may be forced to oviposit in less than optimal sites (Porchuk 1998). Observations of nest success or failure on Pelee Island suggest that suboptimal nests (e.g. under human refuse) may reduce population recruitment rates (Porchuk and Brooks 1995).

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Habitat loss and degradation

Loss of habitat quantity and quality continues to be a threat to the Blue Racer population on Pelee Island. Whether there has been a net loss of habitat since the previous recovery strategy was drafted in 2005 has not been determined. However, there are undoubtedly areas where Blue Racers used to be observed regularly but now appear to be unsuitable based on both the advanced succession of the vegetation community and lack of observations of the species (J. Hathaway pers. comm. 2013). Whereas certain types of habitat loss are obvious (e.g. hedgerow removal and conversion to agriculture), other types of land use change are more subtle (e.g. succession of vegetation communities, removal of non-native grasses). Advanced succession of vegetation communities has been recognized as a factor that could reduce the quantity and quality of Blue Racer habitat since at least 1991 (Kamstra 1991). Another factor that makes it difficult to assess whether habitat loss has occurred since 2005 is that there are areas being removed from agricultural production as part of changes in land ownership and use, thus some of these areas will become potential habitat for Blue Racer.

Anthropogenic refuse such as sheet metal, abandoned cars and farm equipment are discarded throughout the island and are frequently used by Blue Racers for shelter and occasionally nesting (Porchuk 1998). Refuse providing shelter is considered beneficial to Blue Racers; however, eggs laid under exposed sheet metal are doomed to failure because of extreme temperature and moisture fluctuations (Porchuk 1996). Of nine Blue Racer clutches laid under sheet metal and wooden boards, only one clutch remained viable until hatching occurred.

Although it has yet to be quantified, the impacts of blasting on subterranean structures such as hibernacula may have adverse effects on habitat.

Vehicular mortality

Vehicular mortality has always been considered a key threat to the Blue Racer population on Pelee Island (Kamstra 1991, Porchuk 1998, Willson and Rouse 2001). There are often peaks in road mortality levels over the course of an active season. For example, mature males may move more extensively during the mating season and females often move substantial distances to find suitable nesting habitat (Porchuk 1996). Additionally, hatchling Blue Racers are often found dead on Pelee Island’s roads during late August and Septemberember, particularly along East Shore Road where hatchlings move inland from shoreline nest sites (Porchuk 1996). Adult Blue Racers often cross roads relatively quickly compared to the other large snakes on the island; thus, this species is most at risk of being killed on the roads when traffic volume and driving speeds are high (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data). Roadkill surveys were conducted for all snake species from 1993 to 1995 (Brooks and Porchuk 1997), 1998 to 1999 (Brooks et al. 2000) and during the springs of 2000 to 2002 (Willson 2002). During the most intensive survey, a total of 78 Blue Racers (33 adults, 45 subadults) were found road-killed from 1993 to 1995 (Brooks and Porchuk 1997). It is unknown whether mortality at these levels would have long-term population consequences similar to that determined by Row et al. (2007) for Gray Ratsnakes (Pantherophis spiloides) in eastern Ontario; however, given the isolation of the Blue Racer population, it seems very likely that vehicle-induced mortality on roads is a significant threat to survival and recovery (Willson and Rouse 2001).

Direct mortality due to farm machinery has also been documented (Porchuk 1996) and four adult Blue Racers were found killed by lawn mowers between 1993 and 1995 (Brooks and Porchuk 1997). Off-road vehicles also pose a threat to Blue Racers, particularly in shoreline areas where hatchlings and eggs can be killed or destroyed while still within nesting habitats (Porchuk 1998).

Intentional persecution

Snakes regularly elicit reactions of fear or hostility from the general public, and as a result, intentional killing of snakes is not uncommon (Ashley et al. 2007). At least three Blue Racers were shot by pheasant hunters during the study by Porchuk (1996) and three Eastern Foxsnakes were also intentionally killed by humans during the same study period (Porchuk 1998).

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Habitats created as part of conservation efforts

Hibernation, nesting and shelter habitats have been created on Pelee Island to increase the quantity and quality of habitat for Blue Racer (Willson and Porchuk 2001; J. Hathaway pers. comm. 2013). At the time the habitats were created it was understood that it may be many years before Blue Racers begin to use the features as habitat (Willson and Porchuk 2001). However, the majority of the created habitats have not been assessed for use by Blue Racer and this information would help inform efforts to enhance habitat for the species.

It is unknown what structural or chemical cues Blue Racers are using to select hibernation, nesting or shelter habitats. This information would help inform efforts to enhance habitat for the species.

Minimum viable population and survey requirements

The Blue Racer has been extensively studied on Pelee Island and much is known about the biological requirements for adult Blue Racers (e.g. space use, key habitat requirements, prey, predators). However, the amount of suitable Blue Racer habitat required to sustain a viable population is unknown. In theory, population modelling could provide estimates of the minimum viable population (MVP) size, the extent to which mortality needs to be reduced to increase survivorship and recruitment, as well as other population parameters. A typical expression of MVP is the smallest isolated population having a 99 percent probability of survival over the next 100 years despite the influences of environmental, demographic and genetic variability and natural catastrophes (Shaffer 1981).

The most effective and implementable program for monitoring the Blue Racer population has not been determined.

Understanding of potential threats

Studies have not been conducted to examine the impact of fertilizer and pesticide use on Pelee Island snakes, thus the effects of such chemicals remain unclear. Residues of toxic compounds were found in three Blue Racers from Pelee Island (organochlorine <1 ppm wet weight, 6.85–24.1 ppm PCB, and 0.03–0.41 ppm of mercury) but were at such low levels that they did not elicit severe toxic chemical contamination (Campbell and Perrin 1991). It is unknown whether there are acute effects of chemical applications on Blue Racers (e.g. when a snake forages in a freshly sprayed field) or if there is a risk of bioaccumulation of toxins.

Wild Turkeys were introduced to Pelee Island in 2002. It is unknown whether this generalist predator may be having an adverse effect on the Blue Racer population (e.g. by preying upon juvenile Blue Racers).

Finally, the drivers of extirpation of Blue Racers from the Ontario mainland are unknown.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Habitat protection and management

- The provincial Endangered Species Act, 2007 (Government of Ontario 2007) came into force in 2008. Habitat protection is provided for Blue Racer under Section 10 of the act.

- As of 2012, the following properties were known to contain Blue Racer habitat and were owned by organizations that have natural heritage protection as one of their primary objectives:

- Lighthouse Point Provincial Nature Reserve (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry; OMNRF);

- Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve (OMNRF);

- Stone Road Alvar Conservation Area (Essex Region Conservation Authority);

- Stone Road Alvar Nature Reserve (Ontario Nature);

- Shaughnessy Cohen Memorial Savanna (see Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) 2008);

- Florian Diamante Nature Reserve (NCC 2008);

- Stone Road Alvar (NCC 2008); and

- Middle Point Woods (NCC 2008).

Blue Racers have been documented at all of these areas with the exception of Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve (Willson 2002). Management at these properties has varied over time according to the objectives of the responsible agencies.

- The owners of some additional lands with Blue Racer habitat or potential Blue Racer habitat have entered into conservation easements with the NCC.

- Landowners whose properties contained Blue Racer habitat (with certain size restrictions) are eligible to apply to participate in the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program (CLTIP). This program offers 100 percent tax relief to landowners for the portion of their property that was considered to be endangered species habitat. Blue Racer habitat was mapped for CLTIP purposes in 1998 using provincial habitat mapping guidelines (OMNR 1998). The CLTIP mapping incorporated historical as well as recent mark-recapture and radiotelemetry data collected from 1992–1998 (Willson and Rouse 2001).

Habitat restoration and creation

Numerous habitat recovery actions have been initiated over the past 30 years on Pelee Island by several organizations for the Blue Racer specifically, and for Pelee Island’s natural heritage areas in general.

- The Wilds of Pelee Island completed several site-specific life science inventories, wildlife and plant monitoring studies and a restoration plan for marginal agricultural lands (ca. 20 ha) adjacent to the existing natural area known as the Pelee Island Winery’s Red Cedar Savanna. Restoration of these agricultural lands to an ecological community with a higher habitat value for Blue Racer was one of the project objectives.

- Hibernation habitat was created using methodology adapted from Zappalorti and Reinert (1994). Four artificial hibernation sites were created in 1996 (of which two remain) on private properties around Pelee Island (Porchuk 1998). One of these sites demonstrated certain over-wintering success in 2001 with Eastern Gartersnake and an Eastern Foxsnake (Porchuk unpub. data). An additional four hibernation sites were constructed in 2000 and 2001 at three different sites (Willson and Porchuk 2001). It is anticipated that these sites will eventually provide long-term, secure over-wintering areas for the Blue Racer, Eastern Foxsnake and possibly Lake Erie Watersnake; however, surveys have not been completed to assess success.

- Nesting habitat was first created in 1997 by placing artificially hollowed cottonwood logs in areas where they were likely to be encountered by female Blue Racers (Porchuk 1998). Based on the findings of Willson (2000a), 15 nesting piles constructed of herbaceous and woody vegetation were created between 2000 and 2005 at several locations on the island in an effort to increase the amount of suitable nesting habitat for Blue Racers and other egg-laying snakes.

- Shelter habitat was created by placing large, flat, limestone rocks in open-canopy locations in 2000 and 2001. These features were created to provide enhanced thermoregulatory opportunities for snakes while limiting predation risks (Willson and Porchuk 2001). Eleven of these habitats were constructed at several locations on the island.

- The NCC has been actively modifying several different ecological communities (e.g. alvar, woodland) within the properties that they manage on Pelee Island since at least 1998 when they purchased the Shaughnessy Cohen Memorial Savanna (Porchuk 2000, NCC 2008). Areas of farmland that have been taken out of production will begin to increase in habitat value to Blue Racers, particularly in the early stages of succession prior to dense shrub growth (MacKinnon 2005).

Public outreach

- In 1989, wildlife-crossing signs were erected along roads on Pelee Island specifically warning motorists to be aware of snakes crossing the roads. These signs were almost immediately removed or vandalized (Porchuk 1998).

- A natural heritage video was created in 1995 by several government and non- government conservation agencies, including the Pelee Island Heritage Centre, and was played in the passenger lounge on every ferry connecting Pelee Island with the Ontario mainland for several years; however, it has not been updated and is no longer played (Porchuk 1998). Copies of the video were also made available for sale. The informative nature of this video may have helped reduce road mortality and direct persecution by educating tourists.

- In 1995, a pamphlet was designed by the Pelee Island Heritage Centre, Essex Region Conservation Authority, Ontario Nature and the Ontario Heritage Foundation, and was made available on the ferry and at the Heritage Centre. The pamphlet provided information on several rare and endangered flora and fauna on Pelee Island including the Blue Racer. Information on how tourists and residents could help to conserve rare species was included. This pamphlet is currently out of print (MacKinnon 2005).

- In addition to the natural heritage video and pamphlet, The Pelee Island Heritage Centre also sold conservation T-shirts as a public outreach initiative.

- From 1993 to 1995, numerous articles, seminars and youth outreach initiatives regarding the Blue Racer were organized by the University of Guelph research team.

- In an effort to show that the preservation of endangered species can be beneficial to the community and local economy, the Wilds of Pelee Island held an Endangered Species Festival on the island in 2001, 2002 and in 2003. It is estimated that $16,000 was generated for the Pelee Island economy during the festival, thus demonstrating that conserving endangered species and their habitats could benefit the island economy through eco-tourism. In 2003, the festival was combined with the 8th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Network bringing in over 220 people from Ontario, and other regions of Canada and the United States (MacKinnon 2005).

- In 2003, the Wilds of Pelee Island published a 72-page, colour guide entitled Pelee Island Human and Natural History: Guide to a Unique Island Community. Photos and text concerning the Blue Racer and other species at risk were featured in the publication.

Research and monitoring

Table 1 summarizes the studies completed up to 2002 that were focused on Blue Racers on Pelee Island.

Since 2002, J. Hathaway has led expeditions, tour groups and habitat restoration outings to the island in May of most years. Because reptiles and amphibians are a highlight of the tours he leads and he was part of the spring survey team (Willson 2002), Blue Racer observations were recorded in areas known to be inhabited by the species (J. Hathaway pers. comm. 2013). In the spring of 2013 researchers from Central Michigan University captured Blue Racers to collect genetic material (J. Crowley pers. comm. 2013).

| Years(s) | Researcher(s) and reference(s) | Nature of investigation (objectives) | Methods | Field work dates | Notable records or results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Campbell (1976) | determine status of Blue Racer on Pelee Island | intensive searching, road cruising | 2–12 May, 30 May to 4 June, 9–13 June, 16–19 July, 24–27 September |

4 Blue Racers captured & 5 observed; in addition to this study, Campbell had been intermittently conducting field work on Pelee Island since 1970; May 1971: female Blue Racer found near old cistern at Fish Point (last reported Blue Racer from this location) |

| 1978 | Ecologistics LTD (1979) | determine whether proposed pit sites (3 & 4) on Browns Road are significant habitat for racers | intensive searching, & set out shelter boards (shingles) | June to November 284.25 person- hours |

confirmed that Blue Racers were extremely difficult to locate during summer months as no Blue Racers were encountered |

| 1984 | Oldham (1984) | document presence of Blue Racers in the Mill Point Area | intensive searching | 6 intermittent trips (21.5 days) from 5 April to 24 September | 5 Blue Racers captured, 1 Blue Racer found dead on road adjacent to Mill Point area; author also plotted 61 reliable Blue Racer encounters from 1969– 1984; 46 records provided by C. Campbell) |

| 1985 | Oldham (1985) | document presence of Blue Racers in the Mill Point Area | intensive searching | 8–14 May, 40 person-hours |

failed to find Blue Racers at Mill Point; however, 3 individuals encountered elsewhere |

| 1991 | Campbell & Perrin (1991) | recommend national status based on all available information | literature & data review | NA | endangered status recommended; COSEWIC formally designates Blue Racer Endangered in Canada |

| 1991 | Kamstra (1991) | formulate Blue Racer recovery plan for Ontario | literature & data review | NA | given the difficulty of locating Blue Racers via regular searching, author recommends shelter board, road survey & radiotelemetry studies |

| 1992 | Blue Racer Recovery Team (Prevett 1994, summarized in Willson 2000b) | determine feasibility of radiotelemetry study | intensive searching, mark-recapture | 2 May, 21 September, 4 October | 2 May: 16 individuals captured indicating radiotelemetry study possible |

| 1992 | Kraus (1992) | document road mortality, set out & monitor shelter boards | road survey & set out shelter boards | 2 May to 15 July (intermittent) | 2 Blue Racers found dead on the road |

| 1993 | Guelph Team led by Porchuk & Brooks (Porchuk 1996, Brooks and Porchuk 1997) | document distribution, ecology & behaviour | intensive searching, mark-recapture, radiotelemetry, road survey | 20 April to 16 October, 31 March to 22 October, 14 April to 27 September |

detailed spatial, ecological& behavioural data obtained, essential habitats identified |

| 1994 | Guelph Team led by Porchuk & Brooks (Porchuk 1996, Brooks and Porchuk 1997) | document distribution, ecology & behaviour | intensive searching, mark-recapture, radiotelemetry, road survey | 20 April to 16 October, 31 March to 22 October, 14 April to 27 September |

detailed spatial, ecological & behavioural data obtained, essential habitats identified |

| 1995 | Guelph Team led by Porchuk & Brooks (Porchuk 1996, Brooks and Porchuk 1997) | document distribution, ecology & behaviour | intensive searching, mark-recapture, radiotelemetry, road survey | 20 April to 16 October, 31 March to 22 October, 14 April to 27 September |

detailed spatial, ecological & behavioural data obtained, essential habitats identified |

| 1996 | Porchuk (unpub. data, summarized in Willson 2000b) | determine effectiveness of erecting hibernacula traps & continue mark- recapture | mark-recapture, hibernacula traps | 19 April to 30 May | individual Blue Racers show significant fidelity to hibernacula |

| 1997 | Guelph Team led by Willson & Brooks (Brooks et al. 2000) | continue monitoring Blue Racer population at Browns Road savanna | mark-recapture, hibernacula traps, road survey | 1 April to 5 June, 1 April to 13 September, 1 April to 1 June |

long term recapture data from individuals dating back to 1992 |

| 1998 | Guelph Team led by Willson & Brooks (Brooks et al. 2000) | continue monitoring Blue Racer population at Browns Road savanna | mark-recapture, hibernacula traps, road survey | 1 April to 5 June, 1 April to 13 September, 1 April to 1 June |

long term recapture data from individuals dating back to 1992 |

| 1999 | Guelph Team led by Willson & Brooks (Brooks et al. 2000) | continue monitoring Blue Racer population at Browns Road savanna | mark-recapture, hibernacula traps, road survey | 1 April to 5 June, 1 April to 13 September, 1 April to 1 June |

long term recapture data from individuals dating back to 1992 |

| 1999 | Porchuk (1998) | formulate official RENEW recovery plan | literature & data review | NA | proactive recovery actions necessary to ensure persistence of Blue Racers on Pelee Island |

| 2000 | Spring Survey Team led by Willson (2000b, 2001, 2002) | conduct systematic survey to document population trend & size | intensive searching along standardized transects & within defined areas mark-recapture | 15 April to 11 May, 13 April to 12 May, 14 April to 15 May |

systematic survey techniques can produce capture rates suitable for population estimation |

| 2001 | Spring Survey Team led by Willson (2000b, 2001, 2002) | conduct systematic survey to document population trend & size | intensive searching along standardized transects & within defined areas mark-recapture | 15 April to 11 May, 13 April to 12 May, 14 April to 15 May |

systematic survey techniques can produce capture rates suitable for population estimation |

| 2002 | Spring Survey Team led by Willson (2000b, 2001, 2002) | conduct systematic survey to document population trend & size | intensive searching along standardized transects & within defined areas mark-recapture | 15 April to 11 May, 13 April to 12 May, 14 April to 15 May |

systematic survey techniques can produce capture rates suitable for population estimation |

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal for the Blue Racer in Ontario is to (1) maintain, or if necessary increase population abundance to ensure long-term population persistence; (2) increase habitat quantity, quality and connectivity on Pelee Island; and (3) continue to assess the feasibility of repatriating the species to portions of its former range on the southern Ontario mainland.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

[converted to a list]

- Protect habitat and connections, and where possible, increase the quantity and quality of available habitat for Blue Racer on Pelee Island.

- Promote protection of the species and its habitat through legislation, policies, stewardship initiatives and land use plans.

- Reduce mortality by minimizing threats.

- Address knowledge gaps and monitor Blue Racer population.

- Continue to assess the feasibility of repatriating Blue Racers to a location on the southern Ontario mainland.

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 3. Approaches to recovery of the Blue Racer in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing | Protection Management |

1.1 Increase amount of habitat available for Blue Racer.

|

|

| Critical | Ongoing | Protection Management |

1.2 Assess quantity and quality of existing and potential Blue Racer habitat.

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Management Stewardship |

1.3 Develop and implement best management practices for restoring and maintaining Blue Racer habitat.

|

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing | Protection Management | 2.1 Develop a habitat regulation and/or habitat description for Blue Racer under the Endangered Species Act, 2007. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Communications Education and Outreach |

2.2 Develop Best Management Practices for minimizing negative impacts on species.

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Stewardship | 2.3 Implement an awareness plan to inform landowners about the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program and the stewardship fund and how they could benefit from protecting and restoring habitat for Blue Racer and other species at risk. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Communications Education and Outreach Stewardship |

2.4 Produce Stewardship Publications.

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Communications Education and Outreach |

2.5 Produce Fact Sheets.

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Communications Education and Outreach |

2.6 Produce Educational Guides.

|

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Ongoing | Communications Education and Outreach |

3.1 Increase Landowner Communications.

|

|

| Beneficial | Ongoing | Communications Education and Outreach |

3.2 Support the Pelee Island Heritage Centre and other island-based conservation and stewardship organizations to do the following.

|

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring and Assessment |

4.1 Determine whether any of the hibernation, nesting or shelter habitats that have been created are being used by Blue Racers.

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research | 4.2 Research the structural and chemical components of hibernation and nest sites to determine how these habitats can be created in ways that maximize the likelihood that they will be used by Blue Racers. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring and Assessment |

4.3 Conduct Population Monitoring.

|

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring and Assessment | 4.4 Determine whether Wild Turkeys are having adverse effects on the Blue Racer population. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring and Assessment | 4.5 Determine if acute effects of chemical applications (i.e., when a snake forages in a freshly sprayed field) or bioaccumulation of toxins pose a risk to Blue Racers. |

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Research Management |

5.1 Determine Feasibility of Repatriation.

|

|

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

Objective 6: Continue to assess the feasibility of repatriating Blue Racers to a location on the southern Ontario mainland

Given the extirpation of the Blue Racer from the Ontario mainland, it is not possible for a natural population to re-establish itself in the absence of active management. Repatriation is the intentional release of individuals of a species to an area formerly occupied by that species but from which it has been extirpated (Reinert 1991, Fischer and Lindenmayer 2000). Previous studies with other snake species suggest that many repatriation efforts are unsuccessful or have unknown results where the measure of success is the establishment of a viable, self-sustaining population (Dodd and Seigel 1991, Fischer and Lindenmayer 2000). Prior to repatriation efforts, Burke (1991) and Reinert (1991) recommend that probable causes of decline be determined (rather than assumed) so that they can be mitigated prior to repatriation efforts (Dodd and Seigel 1991, Caughley 1994, Fischer and Lindenmayer 2000). The establishment of a long- term monitoring program to ascertain success and assure the publication of both positive and negative results is strongly recommended (Burke 1991, Dodd and Seigel 1991, Reinert 1991, Fischer and Lindenmayer 2000).

Any mainland area considered for repatriation must be thoroughly investigated for the presence of key variables that could contribute to Blue Racer survival (e.g. specific habitat requirements, prey availability, threats). Additionally, a substantial commitment of resources is required for the long-term monitoring of any introduced Blue Racer population to evaluate the success of repatriation efforts. Under current funding formulas for species at risk projects, such a commitment to long-term (ca. 10 year) project is highly unlikely. Considering the amount of resources and expertise required for repatriation, and the limited resources currently available for recovery, resources would be better spent on recovery actions with a higher probability of success. Protection of the existing population on Pelee Island and habitat improvements involve less risk and are likely more viable alternatives to repatriation (Reinert 1991).

M’Closkey and Hecnar (1996) completed an analysis of the repatriation potential of Blue Racer to four locations on the Ontario mainland. They concluded that although the area around Pinery Provincial Park had the most potential as a repatriation site, conservation efforts should focus on the existing population on Pelee Island.

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA 2007, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the authors will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The three most important types of habitat for the Blue Racer, in order of importance, are (1) hibernation habitats, (2) nesting habitats and (3) shelter habitats (e.g. features that facilitate ecdysis, digestion and protection from predators) (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data). Although these three habitats are the most important for maintaining a viable population, other habitats used for foraging, mating and movement are necessary for population persistence (Porchuk 1996, 1998). All of these types of habitat are necessary for individuals of the species to complete their life cycle and thus should be prescribed in a habitat regulation for Blue Racer.

Given the importance and sensitivity to disturbance of hibernation and nesting habitats, it is recommended that these features be recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration. Additionally, shelter habitats that are used by two or more Blue Racers (i.e., are communal) should be recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration. Blue Racers show fidelity to all of these types of habitat, particularly areas used for hibernation (Porchuk 1996, Porchuk and Willson unpub. data).

Hibernation habitat

Additional recommendations pertaining to hibernation habitat to be considered in a habitat regulation are as follows.

- Hibernation habitat should be protected until it is demonstrated that the feature can no longer function in this capacity.

- The area within 120 m of an identified hibernation feature (single site or complex) should be regulated as habitat and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration.

Rationale

Assessments of the suitability of an area to function as hibernation habitat could entail long-term monitoring of a site for use by Blue Racers or an evaluation of a site’s physical condition (e.g. a structurally unstable site could weather or change until access to the interior cavities is no longer possible). The area within 120 m of an identified hibernation feature should be regulated as habitat to ensure that any undocumented holes in the substrate that could be used to access the below-ground feature are protected. Studies on Pelee Island by B. Porchuk and R. Willson (unpub. data) documented hibernation complexes up to 120 m in diameter; thus regulating the area within 120 m of the hibernation feature would ensure that the majority of complexes are protected.

Nesting and communal shelter habitats

Additional recommendations pertaining to nesting and shelter habitat to be considered in a habitat regulation are as follows.

- A naturally occurring nesting habitat or communal shelter habitat (i.e., used by two or more Blue Racers) that has been used at any time in the previous three years should be protected.

- A non-naturally occurring nesting habitat or communal shelter habitat (i.e., used by two or more Blue Racers) should be protected from the time its use was documented until the following November 30.

- The area within 30 m of the boundary of the nesting feature should be regulated as habitat and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration.

Rationale

It is recommended that a distance of 30 m from the boundary of a nesting feature be protected in a regulation to ensure that the thermal properties of the habitat are maintained. Because nesting habitats often occur along the edges of treed areas, particularly along the east shore (Porchuk 1996), protecting habitat within this distance should ensure that there are no trees felled that could alter the solar radiation reaching the nesting feature.

Foraging and mating habitats

Foraging and mating habitats should be recognized as having a moderate sensitivity to alteration. Relative to hibernation, nesting and shelter habitats, the spatial extent of foraging, mating and movement habitats is considerably larger. For example, a nesting feature situated in a fallen and partially decomposed section of tree could be one by two metres. In contrast, foraging and mating habitats are best defined at the level of ecological community (e.g. savanna, woodland) and these areas tend to be several hectares in size.

It is recommended that the following ecological community types on Pelee Island be regulated as foraging and mating habitats when they occur within 2,300 m of a reliable Blue Racer observation:

- alvars (treed, shrub and open types);

- thicket;

- savanna;

- woodland; and

- edge (includes hedgerows and riparian vegetation strips bordering canals).

With the exception of edge, the ecological community types listed above are meant to correspond with the ecological land classifications of Lee et al. (1998). These classifications were adopted by NCC (2008) in their management guidelines for Pelee Island alvars. To correspond with the definition used in the habitat analyses of Porchuk (1996), edge is defined as occurring within five metres of the interface between the two adjoining communities (e.g. forest-woodland, marsh-thicket). For example, where a forest transitions to a farm field, the edge community would extend five metres into the forest and five metres into the farm field. Hedgerows and the majority of the riparian vegetation strips bordering canals will by this definition be considered edge.

Rationale

Foraging and mating activities occur most often, although not exclusively, in these ecological community types (Porchuk 1996, Brooks and Porchuk 1997).

The distance of 2,300 m is recommended because it is approximately the 90 percent quantile of the Maximum Distance from Hibernacula (MDH) values calculated for 25 Blue Racers (14 females; 11 males) radiotracked by Porchuk (1996). Actual value computed is 2,276.8 m. Computation of these values from the 1993–1995 telemetry was completed by R. Willson in 2013 using ArcGIS 10.2 and JMP 10 following Rouse et al. (2011). Based on the dataset analyzed, using an MDH of 2,300 m would encompass the activities of 23 of the 25 Blue Racers (92%). Using the 90 percent quantile with this dataset removed the top two MDH values and thus is an effective way to encompass the majority of the population’s space use while removing the highest MDH values.

Because hibernation habitat is crucial to the survival of snakes inhabiting temperate latitudes, and Blue Racers show a high degree of fidelity to these sites, distance-based metrics that incorporate this habitat feature are the measures of spatial dispersion most relevant to conservation efforts (COSEWIC 2008, Rouse et al. 2011).

Movement habitat

When the space use of the Blue Racer population is examined as a whole and over the entire active season, it is evident that there are not well-defined movement corridors. For example, although most individual Blue Racers tend to follow hedgerows between vegetated patches, other individuals can and will move right through an agricultural field when the crop provides adequate cover. Given the considerable spatial extent of the areas that would be regulated as hibernation, nesting, shelter, foraging and mating habitat as per the recommendations above, it is recommended that no additional areas be regulated as movement habitat.

Glossary

- Alvars:

- Defined in Ontario’s Ecological Land Classification system as having a soil depth of less than 15 cm and tree cover less than 60 percent (Lee et al. 1998).

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC):

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO):

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank:

-

A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure - Dorsum:

- The upper surface of an appendage or body part. Often referred to as the back (opposite of ventral).

- Ecdysis:

- The regular molting or shedding of an outer covering layer (e.g. of skin).

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA):

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Heterogeneity:

- Variety or diversity often associated with a lack of uniformity.

- Hibernaculum:

- A shelter occupied during the winter by a dormant animal.

- Lateral:

- Of or relating to the side.

- Repatriation:

- Returning a species to an area that it formerly occupied.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA):

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List:

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Stochasticity (demographic):

- Random variation in demographic variables, such as birth rates and death rates, sex ratio and dispersal, for which some individuals in a population are negatively affected but not others.

- Stochasticity (environmental):

- Random variation in physical environmental variables, such as temperature, water flow, and rainfall, which affect all individuals in a population to a similar degree.

- Species at risk in Ontario list:

- This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Succession:

- The sequence of vegetation communities that develops from the initial stages of establishment by plants until a stable mature community has formed.

- Ventral:

- The anterior or lower surface of an animal opposite the back (opposite of dorsum).

References

Ashley, E.P., A. Kosloski, and S.A. Petrie. 2007. Incidence of intentional vehicle-reptile collisions. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 12:137-143.

Blouin-Demers, G. and P.J. Weatherhead. 2001. Thermal ecology of black rat snakes (Elaphe obsoleta) in a thermally challenging environment. Ecology 82:3025-3043.

Brooks, R.J. and B.D. Porchuk. 1997. Conservation of the endangered blue racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island, Canada. Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 26 pp.

Brooks, R.J., R.J. Willson and J.D. Rouse. 2000. Conservation and ecology of three rare snake species on Pelee Island. Unpublished report for the Endangered Species Recovery Fund. 21 pp.

Burke, R.L. 1991. Relocations, repatriations, and translocations of amphibians and reptiles: taking a broader view. Herpetologica 47:350-357.

Burkey, T.V. 1995. Extinction rates in archipelagoes: implications for populations in fragmented habitats. Conservation Biology 9:527-541.

Campbell, C.A. 1976. Preliminary field study of the blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island, Ontario. Wildlife Branch, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Chatham District. 69 pp.

Campbell, C.A. and D.W. Perrin. 1991. Status of the blue racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii), in Canada. 42 pp.

Carfagno, G.L.F. and P.J. Weatherhead. 2006. Intraspecific and interspecific variation in use of forest-edge habitat by snakes. Canadian Journal of Zoology 84:1440-1452.

Caughley, G. 1994. Directions in conservation biology. Journal of Animal Ecology 63:215-244.

Conant, R. and J.T. Collins. 1998. A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of eastern and central North America. 3rd, expanded edition. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, Massachusetts.

COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Blue Racer Coluber constrictor foxii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 17 pp.

COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Eastern Foxsnake, Elaphe gloydi, Carolinian Population and Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 45 pp.

Crowley, Joe, pers. comm. 2013. Email correspondence to R. Willson. August 2013. Herpetology Species at Risk Specialist, Species at Risk Branch, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario.

Dodd, C.K.J. and R.A. Seigel. 1991. Relocation, repatriation, and translocation of amphibians and reptiles: are they conservation strategies that work? Herpetologica 47:336-350.

Ecologistics Ltd. 1979. Pelee Island Blue Racer Study. Report for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southwestern Region. 13 pp.

Ernst, C.H. and E.M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Fitch, H.S. 1963. Natural history of the racer Coluber constrictor. University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History 15:351-468.

Fischer, J. and D.B. Lindenmayer. 2000. An assessment of the published results of animal relocations. Biological Conservation 96:1-11.

Government of Ontario. 2007. Endangered Species Act, 2007, S.O. 2007, c 6. Harding, J.H. 1997. Amphibians and reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Hathaway, Jeff, pers. comm. 2013. Email correspondence to R. Willson. August 2013 Herpetologist, species at risk educator.

Kamstra, J. 1991. Blue racer recovery plan for Ontario. Gartner Lee Limited, Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Southwestern Region. 33 pp. + 5 appendices.

Kamstra, J., M.J. Oldham, and P.A. Woodliffe. 1995. A life science inventory and evaluation of six natural areas in the Erie Islands, Essex County, Ontario: Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve, Lighthouse Point Provincial Nature Reserve, Stone Road complex, Middle Point, East Sister Island Provincial Nature Reserve and Middle Island. Aylmer District (Chatham Area), Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 140 pp.

Kraus, D.A. 1992. Final report for the Ontario herpetofaunal summary. Report for the Essex Region Conservation Authority. 24 pp.

Lawson, A. 2005. Potential for gene flow among Foxsnake (Elaphe gloydi) hibernacula of Georgian Bay, Canada. M.Sc. thesis. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario.

Lee, H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig, and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological land classification for Southern Ontario: first approximation and its application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch.

MacKinnon, C.A. 2005. (March 2005 Draft). National recovery plan for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii). Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW). Ottawa, Ontario.

M’Closkey, R.T. and S.J. Hecnar. 1996. Analysis of translocation potential of several designated herptiles at selected southern Ontario protected areas. Final Report of Project Number PP92-03 to Parks Canada. 99 pp.

Minton, S.A. 1968. The fate of amphibians and reptiles in a suburban area. Journal of Herpetology 2:113-117.

Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC). 2008. Management guidelines: Pelee Island alvars. NCC–Southwestern Ontario Region. London, Ontario. 43 pp.

Oldham, M.J. 1984. Update on the status of the blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island, Ontario, with special reference to the Mill Point area. Chatham District, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Oldham, M.J. 1985. Blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii), reconnaissance study at Mill Point, Pelee Island, Ontario. Chatham District, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

OMNR. 1998. Guidelines for mapping endangered species habitats under the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program. Natural Heritage Section, Lands and Natural Heritage Branch, Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario.

Porchuk, B.D. 1996. Ecology and conservation of the endangered blue racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island, Canada. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario.

Porchuk, B.D. 1998. Canadian Blue Racer snake recovery plan. Report prepared for the Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW) committee. 55 pp.

Porchuk, B.D. 2000. Pelee Island conservation plan. Final report to World Wildlife Fund Canada. 9 pp.

Porchuk, B.D. and R.J. Brooks. 1995. Natural history: Coluber constrictor, Elaphe vulpina and Chelydra serpentina. Reproduction. Herpetological Review 26:148.

Prevett, J.P. 1994. National recovery of the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii). Draft recovery plan, May, 1994.

Prior, K.A. and P.J. Weatherhead. 1996. Habitat features of black rat snake hibernacula in Ontario. Journal of Herpetology 30:211-218.

Prior, K.A., G. Blouin-Demers, and P.J. Weatherhead. 2001. Sampling biases in demographic analyses of black rat snakes (Elaphe obsoleta). Herpetologica 57:460-469.

Reinert, H.K. 1991. Translocation as a conservation strategy for amphibians and reptiles: some comments, concerns, and observations. Herpetologica 47:357-363.

Rosen, P.C. 1991. Comparative ecology and life history of the racer (Coluber constrictor) in Michigan. Copeia 1991:897-909.

Rouse, J.D. 2006. Spatial ecology of Sistrurus catenatus catenatus and Heterodon platirhinos in a rock-barren landscape. M.Sc. thesis. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario.

Rouse, J.D., R.J. Willson, R. Black, and R.J. Brooks. 2011. Movement and spatial dispersion of Sistrurus catenatus and Heterodon platirhinos: implications for interactions with roads. Copeia 2011:443-456.

Rowell, J.C. 2012. The Snakes of Ontario: Natural History, Distribution, and Status. Art Bookbindery, Canada.

Shaffer, M.L. 1981. Minimum population sizes for species conservation. BioScience 31:131-134.

Whitaker, P.B. and R. Shine. 2000. Sources of mortality of large elapid snakes in an agricultural landscape. Journal of Herpetology 34:121-128.

Willson, R.J. 2000a. The thermal ecology of gravidity in eastern fox snakes (Elaphe gloydi). M.Sc. thesis. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario.

Willson, R.J. 2000b. A systematic search for the Blue Racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island. Report for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 22 pp. + digital appendices.

Willson, R.J. 2001. A systematic search for the blue racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island: year II. Report for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 18 pp. + digital appendices.

Willson, R.J. 2002. A systematic search for the blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island (2000–2002). Final report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 38 pp. + digital appendices.

Willson, R.J. and B.D. Porchuk. 2001. Blue Racer and Eastern Foxsnake habitat feature enhancement at Lighthouse Point and Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserves: 2001 final report. Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 11 pp.