Butternut Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the Butternut a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

2013

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Poisson, G., and M. Ursic. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the Butternut (Juglans cinerea) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 12 pp. + Appendix vii + 24 pp. Adoption of the Recovery Strategy for the Butternut (Juglans cinerea) in Canada (Environment Canada 2010).

Cover illustration: Photo by Rose Fleguel, Kemptville, Ontario

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

ISBN 978-1-4606-0534-9 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Cathy Darevic au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Authors

Geri Poisson and Margot Ursic – Beacon Environmental Limited

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank those who participated in the Butternut workshops held in March and June of 2012 and/or provided comments on the first version of the draft addendum. Their expertise and insights provided a more in-depth understanding of Butternut and Butternut canker, as well as the state of the science with respect to both of these species.

Thanks are extended to:

Amelia Argue, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR)

Greg Bales, OMNR

Kim Borg, Parks Canada Agency

Barb Boysen, Forest Gene Conservation Association, OMNR

Dr. Kirk Broders, University of New Hampshire

Vivian Brownell, OMNR

Tony Bull, Ontario Woodlot Association

Dawn Burke, OMNR

Rosalind Chaundy, Beacon Environmental Limited

Ken Elliott, OMNR

Rose Fleguel, Consultant, Kemptville, Ontario

Sean Fox, University of Guelph

Ken Goldsmith, Bruce County

Marie-Ange Gravel, OMNR

Krista Holmes, Environment Canada

Anita Imrie, OMNR

Leanne Jennings, OMNR

Bohdan Kowalyk, OMNR

Stephen McCanny, Parks Canada Agency

Dr. John McLaughlin, OMNR

Dr. Brian Naylor, OMNR

John Osmok, OMNR

Bill Parker, OMNR

Jim Rice, OMNR

Jim Saunders, OMNR

Terry Schwan, OMNR

Barbara Slezak, Environment Canada

Dr. Eric Snyder, OMNR

Martin Streit, OMNR

Shaun Thompson, OMNR

Ken Ursic, Beacon Environmental Limited

Bree Walpole, OMNR

Dr. Richard Wilson, OMNR

Dr. Keith Woeste, Purdue University/United States Department of Agriculture

Heather Zurbrigg, OMNR

Special thanks are extended to Dr. Keith Woeste, Dr. Kirk Broders, Dr. John McLaughlin and Dr. Richard Wilson for their workshop presentations and sharing their technical expertise, and to Barb Boysen, Dr. Eric Snyder and Vivian Brownell for their extensive technical input and guidance.

Input from all of these individuals was instrumental in drafting this addendum.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Butternut was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Adoption of the recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to that species.

Butternut is listed as endangered on the SARO List. The species is also listed as endangered under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Butternut in Canada in 2010 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Species assessment and classification

Common name: Butternut

Scientific name: Juglans cinerea

SARO List Classification: Endangered

SARO List History: Endangered (2008), Endangered – Not Regulated (2004)

COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2003)

SARA Schedule 1: Endangered (July 2005)

Conservation status rankings: GRANK: G4 NRANK: N4 SRANK: S3?

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

Area for consideration in developing a Habitat Regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the authors will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

It is recommended that the area considered in developing a habitat regulation for Butternut include a minimum radius of 25 m from the base of the stem of the tree, irrespective of the tree’s size. Given what is currently known about Butternut canker (the disease that is the primary reason that the species is endangered), and Butternut as a species, regulating a minimum radius of 25 m around each tree is an appropriate approach for trying to ensure that:

- the habitat conditions required for the survival of each tree can be maintained, including area for the potential growth of trees that may survive to maturity; and

- habitat for regeneration that occurs within this radius is also protected.

It is further recommended that the habitat regulation be applied strictly to Butternut trees that are healthy

- naturally-occurring (i.e., that are not planted); or

- planted as a requirement of a permit issued under section 17 of the ESA, or are progeny of trees that were planted to satisfy such a requirement (e.g., for overall benefit or as part of an approved planting plan).

It is also recommended that areas covered by impervious surfaces (e.g., paved roads, sidewalks, buildings) as a result of existing and approved land uses, be excluded from the regulated area.

If, in the future, new scientific evidence indicates that regulation of additional habitat areas may reasonably contribute to achieving the recovery goals for Butternut, then this information should be considered in developing or revising the habitat regulation.

General considerations and rationale

Defining an appropriate area for habitat regulation for Butternut is particularly challenging because of the diversity of habitats that the species occupies in Ontario combined with the fact that the primary threat to the species is a disease (i.e., Butternut canker). The federal recovery strategy acknowledges this challenge, and as a result does not define the species' critical habitat. Nonetheless, Ontario’s ESA allows for the description and identification of its habitat in order to provide an appropriate level of habitat protection to help ensure that in situ recovery for this species remains feasible.

Butternut tends to occur sporadically, as individuals or in small groups, in both deciduous and mixed forests, and although its habitat needs have not been well-studied, it is known to occur in both upland and lowland forests and under a wide range of soil conditions (Fowells 1965, Farrar 1995, Cogliastro et al. 1997, Nielsen et al. 2003, Hoban 2010). Rink (1990) observes that it grows best on stream bank sites and well- drained soils, but also occurs on dry or infertile soils, particularly those of limestone origin. Butternut is known to grow poorly under persistently wet conditions and to show improved vigour under conditions of partial or full light (Schlarbaum et al. 2004, Brosi 2010, Hoban 2010, Dr. K. Woeste, pers. comm. 2012). Field researchers and stewardship technicians in Ontario have observed that the species seems to exhibit more vigour and regeneration in open conditions, and consequently encourage selection cutting around retainable Butternut trees (G. Bales, pers. comm. 2012, B. Boysen, pers. comm. 2012, R. Fleguel, pers. comm. 2012). Beyond these preferences, Butternut’s specific habitat requirements are not well understood.

Butternut canker is caused by a fungal infection of the pathogen Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum

In Ontario, Butternut’s range is restricted to the southern and eastern portions of the province. In parts of eastern and much of southern Ontario, habitat loss and degradation as a result of alternate land uses (e.g., development) may compound the threat of Butternut canker. This is particularly relevant for Butternut occurring in suburban and peri-urban habitats, such as hedgerows and edges of farm fields, and within natural and open spaces in urban areas or areas becoming urbanized where the trees are likely to be subject to a variety of anthropogenic impacts.

Another factor that compounds the impacts of the canker on Butternut is its naturally low levels of regeneration. Butternut, as its name suggests, is a large-seeded, rodent- dispersed species that appears to have relatively restricted dispersal distances (Hewitt and Kellman 2002) and seed yields with low viability (Rink 1990). Butternut canker is known to infect seeds, but the extent to which this infection impacts viability is unknown. The occurrences of viable seed are further reduced where the canker has already impacted the local populations, and diseased and dead trees are no longer contributing to the seed pool. Butternut researchers and field technicians have reported that, based on their incidental observations, Butternut is regenerating in relatively low numbers across its range in Ontario (G. Bales, pers. comm. 2012, R. Fleguel, pers. comm. 2012, R. Wilson, unpub. data 2012).

If individual trees and populations of Butternut have or are able to develop resistance or tolerance to the canker, protection of these trees would contribute significantly to the recovery of the species (Environment Canada 2010). If it turns out that genetics plays a role in disease resistance or tolerance, then the retention of those genes throughout the species' geographic range in Ontario will be key to the survival and recovery of the species

- support the longevity and continued reproduction of apparently healthy trees;

- allow for the study of the disease progression and potential environmental conditions that may affect the tree’s response to the canker; and

- allow for the discovery or development of canker-resistant or canker-tolerant trees.

Specific considerations and rationale

The recommended regulated area includes considerations for: (i) the habitat of the individual trees that occur on the landscape and (ii) habitat for their regeneration.

Regulation of habitat of the individual existing tree

Although habitat types currently associated with Butternut are too varied and widespread to simply regulate, the area immediately adjacent to, and surrounding, individual trees should be regulated because activities within this area have the potential to directly impact the tree’s survival and development, as well as its ability to regenerate. Examples of negative impacts that can result from activities within and adjacent to the tree’s root zone include: exposure of the rooting zone, alteration of the soil nutrient content, alteration of the soil chemistry and acidity levels, the addition of deleterious substances, soil compaction, and reduction of air and water penetration into the soil if fill or other materials are added. Regulating habitat, both within and adjacent to the tree’s root zone, can protect the tree from activities that may compromise its health.

Notably, one type of disturbance that may be beneficial to Butternut health is that which increases the tree’s exposure to light. Butternuts tend not to be negatively impacted by increased exposure to light and, in fact, seem to exhibit more vigour under high light conditions (Schlarbaum et al. 2004, Brosi 2010). However, there is also some evidence that human disturbance in the landscape can encourage hybridization

The recommended approach for identifying a regulated area is based on established methods for determining appropriate tree protection zones, including consideration of the tree’s rooting area and consideration for impacts related to activities outside the rooting zone. The recommended approach also takes into consideration the fact that Butternut is:

- an endangered tree whose habitat requirements are not well understood;

- a tree species known to be sensitive to root severing, somewhat sensitive to soil compaction and prolonged periods of flooding, and sensitive to development and urban stressors (Huff 2012, Johnson 2012); and

- primarily threatened by a disease that presents a serious stressor to the tree above and beyond other stressors that may be affecting the tree.

An established arboriculture approach to individual tree protection is to multiply the tree’s diameter by a multiplier to identify an appropriate "tree protection" or "critical root protection" zone around the tree (e.g., Matheny and Clark 1998, Dicke 2004, Johnson 2012). The size of the multiplier depends on the species' known sensitivities to disturbance and its age. However, this approach is not considered entirely appropriate for Butternut because: (i) the identified zone is intended to specifically protect the tree in its current state of development from activities that could harm it in adjacent lands and (ii) this approach is not intended to capture the entire rooting zone that is estimated by Johnson (2012) to be double the "critical root protection" zone, but will capture enough of the rooting zone to support a healthy tree’s continued survival and growth.

The recommended approach for identifying a regulated area around Butternut, called the Site Occupancy Method, is comparable to the arboriculture method described above, but considered more appropriate for Butternut given its status and known sensitivities. Coder’s (1995) Site Occupancy Method is specifically intended to identify a tree protection area comparable to that found within a tree’s natural forested setting and to allow room for future root growth. This method uses a multiplier of 68.58 cm (2.25 feet or 27 inches) for every 2.54 cm (one inch) of predicted diameter of the tree at maturity. The intent of the regulated area is to protect the existing tree as well as its potential habitat, should it reach maturity; therefore this approach is considered suitable.

The available literature indicates that Butternut generally grows to heights of 12 to 18 m and reaches diameters between 30 and 75 cm at maturity (Dirr 1975, Rink 1990, Kershaw 2001). The largest documented Butternut in southern Ontario has a diameter of 116 cm and is 24.5 m tall (OFA 2012), and it is not uncommon for larger specimens to reach heights of up to 30 m and diameters between 80 and 100 cm (Rink 1990, G. Poisson, pers. obs.). Based on this information, a conservative maximum potential diameter for the species is considered to be about 91 cm (or 36 inches as noted by Rink 1990). It is therefore recommended that the habitat regulation zone for Butternut trees be based on the maximum potential diameter at maturity of 91 cm (36 inches).

Summary calculation:

91 cm (maximum potential diameter of a mature Butternut) ÷ 2.54 x 68.58 cm (multiplier for recommended habitat protection area)

= 24.57 m radius around the stem of the tree

= 25 m rounded up.

Another commonly used method for determining a tree protection zone is the Tree Height Method (Matheny and Clark 1998), whereby the radius of the protection zone is equal to the height of the tree. In this case we would use the potential height of a mature Butternut (25 m).

Based on the rationale and calculations above, regulation of a 25 m radius of suitable habitat surrounding individual Butternut trees is recommended.

Protection of Habitat for Regeneration

Under the ESA, a regulation prescribing an area as the habitat of a species may prescribe areas where the species lives, used to live or is believed to be capable of living (OMNR 2008). In the case of Butternut, protecting areas where the species has a high likelihood of regenerating would support its recovery, particularly if the seedlings manifest resistance or tolerance. Hoban (2010) found that seedling recruitment was sparse and unpredictable in upland habitats, but somewhat more regular in riparian settings subject to frequent local disturbances from flooding. Given that the regeneration habitat for Butternut, much like the habitat for established trees, appears to be varied and sporadic within its range, it is hard to identify specific habitat types that are likely to be suitable for regeneration.

The literature recognizes that large-seeded species, like Butternut, appear to have relatively small seed-dispersal ranges from the parent tree. Butternut seeds are heavy nuts that are dispersed by gravity, water, squirrels and other small mammals. Squirrels, the main dispersers of Butternut seeds, will transport the seeds an average of 15 to 20 m, but up to around 100 m (Hoban 2010). Hewitt and Kellman (2002) found that the bulk of the Butternut seedlings that established themselves did so within 25 to 50 m from the parent tree.

Dispersal that is relatively close to the parent tree can support seedling establishment if suitable conditions are present. One advantage of large-seeded species having short dispersal distances is that the environmental conditions tend to be favourable for germination and survival because they are typically similar to those in which the parent tree has established (Barnes et al. 1998). Additionally, Butternut is a species that is intolerant of shade and requires canopy gaps to reach reproductive maturity. For these types of species, Wenny (2001, pg. 53) states that: "Widespread dispersal of seeds in the area around the parent plants will maximize the number of different sites occupied and increase the chance that some sites will become suitable in the future". Therefore, the area immediately around the tree can provide potential regeneration habitat, assuming that conditions are suitable within this area for seedling establishment.

It is recommended that the radial distance of 25 m from the base of an established, healthy tree also be regulated to support regeneration of the species given that: (i) based on the available information, potential Butternut regeneration cannot be linked to specific habitat types, (ii) most Butternut seeds do not appear to travel very far from the parent tree (Hewitt and Kellman 2002, Hoban 2010) and (iii) the chances of recruitment success may be better closer to the parent tree where there are suitable microsites available (Barnes et al. 1998, Wenny 2001, OMNR 2010).

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

Critical habitat: Habitat recognized under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species' critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species.

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This Act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that, at the time the Act came into force, needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedules 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Bales, G., pers. comm. 2012. Workshop participant, March 7 & June 22, 2012. Stewarship Co-ordinator, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Barnes, B.V., D.R. Zak, S.R. Denton, and S.H. Spurr. 1998. Forest Ecology. 4th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. 774 pp.

Boysen, B., pers. comm. 2012. Workshop participant, March 7 & June 22, 2012. Coordinator, Forest Gene Conservation Association. Peterborough, ON

Broders, K.D., A. Boraks, A.M. Sanchez, and G.L. Boland. 2012. Population structure of the butternut canker fungus, Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum, in North American forests. Ecology and Evolution 2(9): 2114–2127.

Brosi, S.L. 2010. Steps Toward Butternut (Juglans cinerea L.) Restoration. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Web site: http://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/779 [accessed May 12, 2012].

Coder, K.D. 1995. Tree quality BMPs for developing wooded areas and protecting residual trees. G.W. Watson and D. Neely (eds.) In Trees and Building Sites. International Society of Arboriculture, Savoy, Illinois.

Cogliastro, A., D. Gagnon, and A. Bouchard. 1997. Experimental determination of soil characteristics optimal for the growth of ten hardwoods planted on abandoned farmland. Forest Ecology and Management 96: 49-63.

Dicke, S.G. 2004. Preserving Trees in Construction Sites. Mississippi State University Extension Service, Raymond, Mississippi. Publication 2339. 11 pp.

Dirr, M.A. 1975. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants. 6th edition. Stipes Publishing, Champaign, Illinois. xxxix + 1325 pp.

Environment Canada. 2010. Recovery Strategy for the Butternut (Juglans cinerea) in Canada. Species At Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vii + 24 pp.

Farrar, J.L. 1995. Trees in Canada. Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited and the Canadian Forest Service. 502 pp.

Fleguel, R. B., pers. comm. 2012. Workshop participant, March 7 & June 22, 2012. Butternut Recovery Technician, Rideau Valley Conservation Authority.

Fowells, H.A. 1965. Butternut, Pg. 208. In Silvics of Forest Trees of the United States. United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook No. 271.

Hewitt, N., and M. Kellman. 2002. Tree seed dispersal among forest fragments: II. Dispersal abilities and biogeographical controls. Journal of Biogeography 29: 351-363.

Hoban, S.M., T.S. McCleary, S.E. Schlarbaum, S.L. Anagnostakis, and J. Romero-Severson. 2012. Human-impacted landscapes facilitate hybridization between a native and an introduced tree. Evolutionary Applications 5(7): 720-731.

Hoban, S. M. 2010. Natural and Anthropogenic Influences on Population Dynamics of Butternut (Juglans cinerea L.). Ph.D. dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA. 179 pp.

Huff, C. 2012. Average Urban Tolerance of Trees in Ottawa. City of Ottawa, Forestry Services. Web site: http://www.ottawahort.org/urbantree.htm [link inactive] [accessed May 3, 2012].

Johnson, G.R. 2012. Protecting Trees from Construction Damage: A Homeowner’s Guide. Regents of the University of Minnesota. (Revised 1999). Web site: http://www.extension.umn.edu/distribution/housingandclothing/DK6135.html#Root [accessed July 20, 2012].

Kershaw, L. 2001. Trees of Ontario. Lone Pine Publishing. 574 pp.

B. Kowalyk, per comm. 2012. District Forester, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aurora, ON

Matheny, N.P., and J.R. Clark. 1998. Trees and Development: A Technical Guide to Preservation of Trees During Land Development. International Society of Arboriculture, Urbana, Illinois. 184 pp.

Nielsen, C., M. Cherry, B. Boysen, A. Hopkin, J. McLaughlin, and T. Beardmore. 2003. COSEWIC status report on Butternut Juglans cinerea in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 32 pp.

Ontario Forestry Association (OFA). 2012. Honour Roll. As listed in its Honour Roll of Ontario trees. Web site: http://www.oforest.ca/honour_roll/trees.php [link inactive] [accessed November 19, 2012].

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). 2008. Habitat protection for endangered, threatened and extirpated species under the Endangered Species Act, 2007. Species At Risk Policy 4.1. Species at Risk Section, Fish and Wildlife Branch, Natural Resources Management Division. 16 pp.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). 2010. Forest Management Guide for Conserving Biodiversity at the Stand and Site Scales. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Toronto. 211 pp. Web site: /document/forest-management-conserving-biodiversity-stand-and-site-scales [accessed May 3, 2012].

Rink, G. 1990. Juglans cinerea L. Butternut. Pp. 386-390, in R.M. Burns and B.H. Honkala (tech. coords.). Silvics of North America. Vol. 2 Hardwoods. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Agriculture Handbook. 654 pp. Web site: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_2/juglans/cinerea.htm [accessed November 15, 2012].

Schlarbaum, S.E., R.L. Anderson, M.E. Ostry, S.L. Brosi, LM. Thompson, S.L. Clark, F.T. van Manen, P.C. Spaine, C. Young, S.A. Anagnostakis, and E.A. Brantley. 2004. An integrated approach for restoring Butternut to eastern North American fore Pp. 156-158, in Li, B. and S. McKeand (eds). Forest Genetics and Tree Breeding in the Age of Genomics: Progress and Future. Proceedings of the International Union of Forest Research Organizations, Division 2 Joint Conference. Web site: http://www.ces.ncsu.edu/nreos/forest/feop/Agenda2004/iufro_genetics2004/proceedings.pdf [link inactive] [accessed July 20, 2012].

Wenny, D.G. 2001. Advantages of seed dispersal: A re-evaluation of directed dispersal. Evolutionary Ecology Research 3: 51-74.

Woeste K., pers. comm. 2012. Workshop presentation. March 7, 2012. U.S. Forest Service, Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Dept. of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN.

Appendix 1. Recovery Strategy for the Butternut (Juglans cinerea) in Canada

About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series

What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)?

SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is "to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.

What is recovery?

In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species' persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured.

What is a recovery strategy?

A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage.

Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Depending on the status of the species and when it was assessed, a recovery strategy has to be developed within one to two years after the species is added to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. A period of three to four years is allowed for those species that were automatically listed when SARA came into force.

What’s next?

In most cases, one or more action plans will be developed to define and guide implementation of the recovery strategy. Nevertheless, directions set in the recovery strategy are sufficient to begin involving communities, land users, and conservationists in recovery implementation. Cost-effective measures to prevent the reduction or loss of the species should not be postponed for lack of full scientific certainty.

The series

This series presents the recovery strategies prepared or adopted by the federal government under SARA. New documents will be added regularly as species get listed and as strategies are updated.

To learn more

To learn more about the Species at Risk Act and recovery initiatives, please consult the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry

Recovery Strategy for the Butternut (Juglans cinerea) in Canada 2010

Recommended citation:

Environment Canada. 2010. Recovery Strategy for the Butternut (Juglans cinerea) in Canada.

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa vii + 24 pp.

Additional copies:

Additional copies can be downloaded from the SAR Public Registry.

Cover illustration: Barb Boysen

Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du noyer cendré (Juglans cinerea) au Canada »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment, 2010.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-100-16771-8

Cat. no. En3-4/77-2010E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Declaration

This recovery strategy has been prepared in cooperation with the jurisdictions responsible for the butternut. Environment Canada and the Parks Canada Agency have reviewed and accept this document as its recovery strategy for the butternut, as required under the Species at Risk Act (SARA). This recovery strategy also constitutes advice to other jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved in recovering the species.

The goals, objectives, and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best existing knowledge and are subject to modifications resulting from new findings and revised objectives.

This recovery strategy will be the basis for one or more action plans that will provide details on specific recovery measures to be taken to support conservation and recovery of the species. The Minister of the Environment and the Minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency will report on progress within five years, as required under SARA.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada and the Parks Canada Agency or any other jurisdiction alone. In the spirit of the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, the Minister of the Environment and the Minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency invite all responsible jurisdictions and Canadians to join Environment Canada and the Parks Canada Agency in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the butternut and Canadian society as a whole.

Responsible jurisdictions

Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service

Parks Canada Agency

Government of New Brunswick

Government of Ontario

Government of Quebec

Contributors

Vance, Christine – Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service

Boysen, Barb – Forest Gene Conservation Association

Nielsen, Cathy – Environment Canada

McGarrigle, Mark – New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources

Giasson, Pascal – New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources

Acknowledgements

This strategy was made possible by the hard work that was put into butternut conservation initiatives by many people across the country in the past couple decades – including many who are not mentioned here. An earlier version of this document was formed using draft recovery strategies from Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) and the New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources (NBDNR). A Butternut Coordinating Team with representatives from New Brunswick, Ontario, and Quebec commented on drafts of this strategy. The Coordinating Team included Alan Dextrase (OMNR), Pascal Giasson (NBDNR), Diane Amirault (Environment Canada (EC), Atlantic), Barb Boysen (OMNR), Alain Branchaud (EC, QC), Guy Jolicoeur (Natural Heritage and Parks Directorate, QC), Karine Picard (EC, QC), Isabelle Ringuet (EC, QC), and Luc Robillard (EC, QC). Initial drafts of the document were also reviewed by a butternut expert technical committee which included Nelson Carter (NBDNR), Tannis Beardmore (Natural Resources Canada (NRC), NB), Pierre DesRochers (NRC, QC), Ricardo Morin (NRC, QC) and Judy Loo (NRC, NB). The Ontario Butternut Recovery Team provided many helpful comments and ideas for this strategy. Many other people not listed here in the provinces of Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick also provided thoughtful comments on draft versions of this document. Thanks also to Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service and Ian Parsons for help with distribution maps.

Strategic environmental assessment statement

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. The purpose of the SEA is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally sound decision-making.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to adverse environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts upon non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into the strategy itself, but are also summarized below.

This recovery strategy will clearly benefit the environment by promoting the recovery of butternut. The potential for the strategy to inadvertently lead to adverse effects on other species was considered. The SEA concluded that this strategy will clearly benefit the environment and will not entail any significant adverse effects. Refer to the following sections of the document in particular: Recovery Goals, Recovery Objectives; Effects on other species; and the Approaches Recommended to Meet Recovery Objectives.

Preface

The Species at Risk Act (SARA, Section 37) requires the competent ministers to prepare recovery strategies for listed extirpated, endangered or threatened species. Butternut was listed as Endangered under SARA in July 2005. The Minister of the Environment and the Minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency are the competent ministers for the recovery of the Butternut. Environment Canada led the development of this recovery strategy working in cooperation with the Parks Canada Agency. It has also been prepared in cooperation with the National Butternut Recovery Coordinating Team, the governments of Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick. All responsible jurisdictions reviewed and supported the request to post the strategy.

Executive summary

Butternut (Juglans cinerea L.) is a species of tree designated as Endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) and was listed in July 2005 as Endangered on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA) in Canada. Butternut is an uncommon but widely distributed species that occurs in central and eastern North America. In the past 40 years butternut has undergone serious declines, primarily due to a non-native fungal pathogen which causes a fatal stem and branch disease known as butternut canker (Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum, N.B. Nair, Kostichka & Kuntz). Butternut canker is currently known to exist throughout the range of butternut in Ontario and Quebec, with limited distribution, at present, in New Brunswick. The fundamental threat and principal one noted within the COSEWIC Status Report (Nielsen et al. 2003) is butternut canker. In some provinces, additional pressures on the landscape compound the threat of the canker whereas in others, those threats are not significant at the population level.

There are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the butternut. These unknowns relate to whether there are trees in Canada which are resistant to the butternut canker. Therefore, in keeping with the precautionary principle, a recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA, as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible. This recovery strategy addresses the unknowns surrounding the feasibility of recovery. The long-term recovery goal (>20 years) for butternut is to ensure conditions that will allow for the restoration of viable, ecologically functioning, and broadly distributed populations within its current range in Canada. Short-term objectives are:

- By 2011, develop stewardship and outreach products informing Canadians of the identification, conservation status, conservation mechanisms and management of butternut and on the identification, assessment and management of butternut canker.

- By 2012, collect information on the distribution, abundance and status of butternut and its health across its range in Canada and make it available in a National Database Management System (that is compatible with existing regional Conservation Data Centres).

- By 2014, identify local populations of butternut across its native range and maintain them through focused stewardship in order to increase the likelihood of finding individuals which show resistance to the canker (due to environmental or genetic factors, or a combination thereof).

- By 2014, where the disease is widespread, select, graft and archive at least ten putatively resistant trees in each ecodistrict in support of a future breeding and/or vegetative propagation program to produce resistant trees for restoration, and in support of future critical habitat identification.

- By 2019, address priority knowledge gaps and research necessary for implementing recovery activities (including research into disease resistance and level of adaptive genetic variation, as well as environmental factors that limit the spread of the disease).

The recovery strategy has a strong outreach and stewardship approach and stresses research activities, inventory and monitoring across the butternut range. This strategy emphasizes national and international cooperation, to alleviate redundancy and facilitate sharing of recovery solutions. Where possible, the recovery strategy should be integrated into the management plans of protected areas in which the species occurs and into broader scale conservation and restoration initiatives across New Brunswick, Ontario and Quebec.

Critical habitat is not identified in the recovery strategy. A schedule of studies to gather the information required to identify critical habitat is included.

1. Background

1.1 Species assessment information from COSEWIC

Common Name: Butternut

Scientific Name: Juglans cinerea

COSEWIC Status: Endangered

Last Examination and Change: November 2003

Canadian Occurrence: New Brunswick, Ontario, Quebec

Reason for designation: A widespread tree found as single trees or small groups in deciduous and mixed forests of southern Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick. Butternut canker, which has caused high rates of infection and mortality in the United States, has been detected in all three provinces. High rates of infection and mortality have been observed in parts of Ontario and are predicted for the rest of the Canadian population.

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Endangered in November 2003. Assessment based on a new status report.

1.2 Description of the species

Butternut is a deciduous medium-sized tree with a broad spreading irregularly shaped crown. Mature trees are seldom more than 30 m in height and 91 cm in diameter (Rink 1990). The leaves are pinnately compound with 11-17 leaflets between 9 to 15 cm long (Landowner Resource Centre 1997) that are opposite and almost stalkless (Farrar 1995). Leaves are yellowish-green, densely hairy on the underside and twigs are stout, hairy, and yellowish orange in colour (Farrar 1995) with a chambered pith (Hosie 1990). The terminal bud is elongated, about 1.0 to 1.5 cm long, somewhat flattened and blunt tipped with lobed outer scales (Farrar 1995). Lateral buds are much smaller and rounded, often with more than one bud above the leaf scar (Hosie 1990). The upper margins of the leaf scars are flat and bordered with hair (Farrar 1995). On younger trees, the bark is grey and smooth while older individuals have bark that becomes separated by narrow, dark fissures into wide, irregular, flat-topped, intersecting ridges (Farrar 1995). The fruit is a single-seeded edible nut with a dense layer of short sticky hairs covering the husk and an inner shell with jagged ridges (Nielsen et al. 2003).

The species is similar to black walnut (Juglans nigra L.) but can be distinguished by such characteristics as its hairy twigs and leaves, downy fringe above the bud scar, terminal leaflet that is as large as the lateral leaflets, a dark pith and ovoid hairy fruit with jagged ridges on the shell of the nut. In contrast, black walnut has smooth or only slightly hairy twigs and leaves with the terminal leaflet missing or smaller than the lateral ones; the fruit is globular, nearly hairless, and has rounded ridges on the surface of the shell (Nielsen et al. 2003).

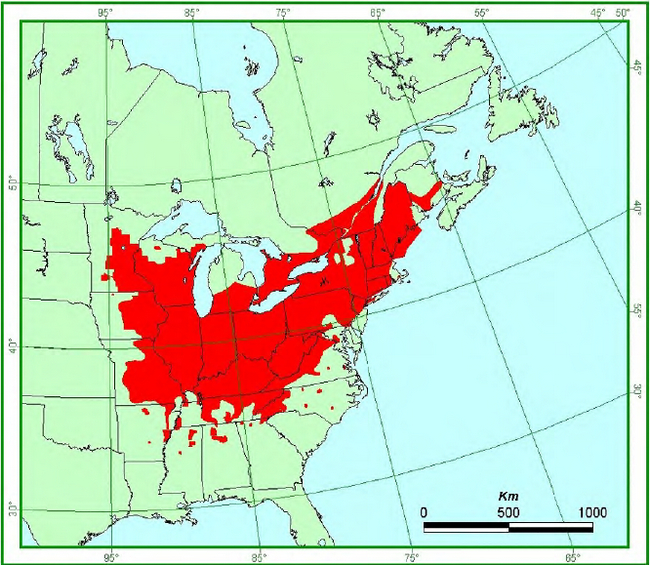

1.3 Populations and distribution

Butternut is native to central and eastern United States and reaches its northern limit in southeastern Canada (Figure 1). The Global status is between 'vulnerable' and 'apparently secure' and its rounded designation is Vulnerable (NatureServe 2005). In the United States, the national status is also between 'vulnerable' and 'apparently secure'. It is found in 32 states where the status varies from 'critically imperilled' to 'apparently secure'. In Canada, butternut is ranked N3N4 (vulnerable to apparently secure) and is native to Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick. It has been introduced as an exotic ornamental in Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. The extent of occurrence is estimated at 121 000 km2. There are an estimated 13 000-17 000 trees in 500 locations reported by landowners in Ontario, but how accurately this reflects the true Ontario population today is not known because there has not been a sufficient, comprehensive survey. The species' abundance has not been estimated in Quebec but its presence has been observed on 378 forest sampling plots, of which 39 have over 25% basal area of butternut (Nielsen et al. 2003). In New Brunswick, there are a total of 151 recorded butternut sites (Butternut Canker in New Brunswick Workshop, February 2004) with a conservative estimate of 7 000-17 000 trees (based upon forest development survey information, permanent sample plots and personal experience of field staff from the New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources, unpublished report). Again, how accurately this estimate reflects the true population in New Brunswick is unknown because there has not been a comprehensive survey.

In Canada, COSEWIC designated the species as Endangered in November 2003, due to the observed and projected decline from butternut canker, a fungal disease that causes mortality. The rate of change in geographical distribution in Canada is unknown; however, in two preliminary butternut surveys done in Ontario as many as 44 - 47 % of sites have trees in poor condition (Nielsen et al. 2003). In Wisconsin, the proportion of infected trees is as high as 91% (Cummings-Carlson 1993).

Figure 1. Butternut range in North America (modified from Rink 1990 and Farrar 1995)

Table 1. Summary of the N-ranks and S-ranks for the states and provinces in which butternut occurs (NatureServe 2005).

| Country | National Rank | Provincial/State Rank |

|---|---|---|

| United States | N3N4 | Alabama (S1), Arkansas (S3), Connecticut (SNR), Delaware (S3), District of Columbia (S1), Georgia (S1S2), Illinois (S2), Indiana (S3), Iowa (SU), Kansas (SNR), Kentucky (S3), Maine (SU), Maryland (S2S3), Massachusetts (S4?), Michigan (S3), Minnesota (S3), Mississippi (S2), Missouri (S2), New Hampshire (S3), New Jersey (S3S4), New York (S4), North Carolina (S2S3), North Dakota (SNR), Ohio (S3), Pennsylvania (S4), Rhode Island (SU), South Carolina (SNR), Tennessee (S3), Vermont (SU), Virginia (S3?), West Virginia (S3), Wisconsin (S3?) |

| Canada | N3N4 | Manitoba (SNA), New Brunswick (S3), Ontario (S3?), Prince Edward Island (SNA), Quebec (S3S4) |

S1: Critically Imperilled, S2: Imperilled, S3: Vulnerable; S3?: inexact numeric rank; S4: Apparently Secure, SNR: Not Ranked/Under Review; SU: Unrankable; SNA: Status Not Applicable; N3: Vulnerable; N4: Apparently Secure.

1.4 Needs of the Butternut

1.4.1 Description of biological needs, ecological role and limiting factors

Butternut is a relatively short-lived species, as compared to other temperate tree species, rarely surviving more than 75 years (Herbert 1976). Butternut flowers from April to June, depending on location. The species is monoecious

Butternut canker is a serious threat and limiting factor for the species. Although healthy butternut trees have grown amongst diseased trees (Ostry et al. 1994), the situation is extremely rare. It has not yet been shown that this putative

1.4.2 Description of habitat needs

Butternut can tolerate a large range of soil types. It typically grows best on rich, moist, well- drained loams often found along stream banks but can also be found on well-drained gravelly sites, especially of limestone origin. Butternut is intolerant of shade and competition, requiring sunlight from above to survive (Rink 1990) but it has the ability to maintain itself as a minor component of forests in later successional stages. As a result, the species is typically scattered throughout a stand and occasionally, groups of butternuts can be found along forest roads, forest edges or anywhere sunlight is adequate to support regeneration through seed. Common associates include basswood (Tilia americana L.), black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.), beech (Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.), black walnut, elm (Ulmus sp.), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis L.), hickory (Carya sp.), oak (Quercus sp.), red maple (Acer rubrum L.), sugar maple (Acer saccharum Marsh.), tulip-tree (Liriodendron tulipifera L.), white ash (Fraxinus americana L.) and yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis Britt.) (Rink 1990). There have been reports of butternut as an associate of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) (OMNR 2000). The climate for butternut varies greatly within its range: mean annual temperature ranges from a maximum of 16°C to a minimum of 4°C and frost-free periods extend from 105 days in the north to 210 days in the south (Rink 1990).

1.5 Threats

The fundamental threat and principal one noted within the COSEWIC Status Report (Nielsen et al. 2003) is butternut canker. In some provinces, additional pressures on the landscape compound the threat of the canker whereas in others, those threats are not significant at the population level. Threats to the survival of the species* and the habitat** are presented in order of significance.

i. Butternut canker*

The most serious and widespread pressure on butternut is a non-native fungal pathogen that causes butternut canker (Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum N.B. Nair, Kostichka & Kuntz). Fungal infection of butternut causes necrosis of cambial tissue which may eventually disrupt nutrient flow. It may take trees more than 40 years to die, but in many cases, death has rapidly followed infection. Mortality after infection appears to be directly related to the size of the tree due to the girdling effect of the cankers as they grow and coalesce (i.e., larger trees generally take longer to succumb to the disease). Thus, as larger trees disappear from the landscape, average time-to-mortality following infection will become shorter and shorter. Following dieback, this species does not leave live root sprouts, usually does not leave viable seed, and stem cankers damage the commercial value of the wood. Once killed the trees rarely sprout and when they do, the sprouts are not known to reach any appreciable size or produce seed (Ostry unpubl. data). Butternut canker is transmitted from tree-to-tree by asexually produced spores (pycnidiospores) carried by wind and rain droplets/aerosol (Tisserat and Kuntz 1983). The fungus can also survive in infected seed stratified at 4°C for up to 18 months (Schultz 2003). Beetles, including some long-horned beetles (Cerambycidae) and weevils (Curculionidae), are known to play a role in fungal transmission (Halik and Bergdahl 2002). Cankers resulting from natural infection have been found over 100 m from the nearest cankered tree (Tisserat and Kuntz 1983). The susceptibility of butternut to the canker is heightened due to its natural history characteristics (e.g. relatively short life span and dependence on openings within the forest canopy for regeneration). Note that care needs to be exercised in evaluating trees for butternut canker so that trees with dead branches are not automatically considered diseased. Another fungus, Melanconis juglandis (Ellis & Everh.) A.H. Graves is often confused with butternut canker but is not lethal (Ostry et al. 1994). It is often found fruiting in its anamorphic state (Melanconium oblongum Berk) on dead butternut branches, sometimes on the same branch as butternut canker (Michler et al. 2005).

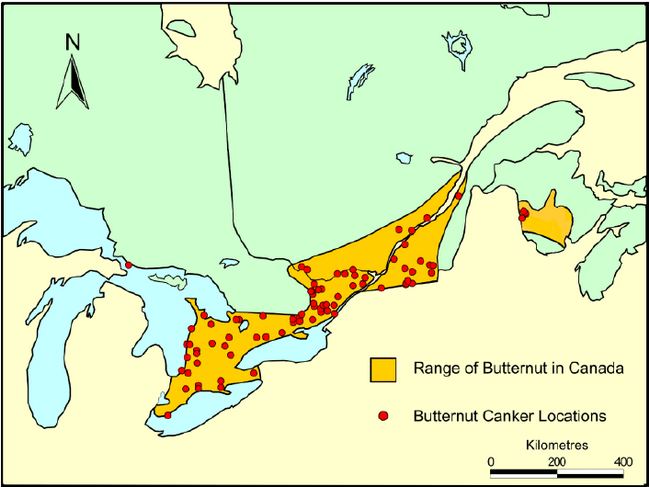

Butternut canker was first collected in Quebec in 1990 (Innes and Rainville 1996), in Ontario in 1991 (Davis et al. 1992) and then in New Brunswick in 1997 (Harrison et al. 1998). Butternut canker is currently known to exist throughout the range of butternut in Ontario and Quebec, with limited distribution, at present, in New Brunswick (Hopkin et al. 2001) (Figure 2). Currently the rates of infection and mortality in Canada are not known, however, in some U.S. states butternut canker has infected as many as 91% of the live butternut in all age classes (Ostry 1997). The disease was first reported from Wisconsin in 1967 (Renlund 1971), but was likely present for several years before then (Kuntz et al. 1979).

Figure 2. Butternut range and known butternut canker locations in Canada (adapted from maps and information provided by Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service).

ii. Harvesting of Trees*

In the absence of the canker, harvesting of butternut would not be a threat to the species. However, in anticipation of mortality from the disease, in some areas, the threat of harvesting may be a more immediate threat than the canker itself. Harvesting of butternut by landowners in anticipation of mortality has already been documented in the U.S. (Ostry and Pijut 2000) and an increased incidence of butternut is already evident in the market (e.g. at log auctions) in Ontario (Boysen unpubl. data). At times the wood has been in great demand as it is sought after as a specialty wood for cabinet-making and other types of woodworking. Currently this threat is greatest in the Ontario portion of the species range but is anticipated to grow with the continued spread of the disease and growing awareness of the disease amongst landowners. Indiscriminate removal of trees that have canker is unwarranted because surviving individuals may have some level of resistance even if they are not canker-free. This threat will result in the loss of individual trees, including putatively resistant trees, and at least in parts of its range, the loss of populations on the landscape. The harvesting of non-infected and putatively resistant trees may reduce genetic diversity. If genetic resistance exists, it appears to be rare and should be preserved on the chance that it may contribute to the recovery of the species.

iii. Habitat loss and degradation**

In most regions, habitat loss is not a major limiting factor for butternut, however, loss of forested habitat to agriculture and urban development remains a stress on the species where forest cover in general is limited (e.g. southwestern Ontario). Butternut also requires specific light and site conditions to successfully regenerate. Unless silviculture practices include a focus on providing conditions required to maintain current populations and achieve natural regeneration of butternut, it is unlikely that there will be increased reproduction in future (Skilling et al. 1993). Much research and work has already been done in this area (Ostry et al. 2003, Ostry et al. 1994, OMNR 2000, Lupien, 2006) and the latest information needs to be communicated to landowners and managers for maintaining butternut on sites which are optimum for growth and reproduction.

iv. Other diseases, insects and exotics*

There are a number of insects and diseases that threaten butternut survival. The extent of the damage varies, but most are not capable of causing mortality on their own. In combination with butternut canker however, these factors increase the stress of individuals, which may result in mortality (see Nielsen et al. 2003 for more details on each):

- Leaf spot (Marssonina juglandis (Lib.) Magnus)

- Armillaria root disease (Armillaria gallica H. Marxm.& Romagn.)

- Butternut curculio (Conotrachelus juglandis Lec.)

- Fall webworm (Hyphantria cunea (Drury))

- Walnut caterpillar (Datana integerrima G&R)

- Walnut shoot moth (Acrobasis demotella Grote)

- Bunch broom disease (caused by phytoplasmas

footnote v - Fusarium spp. canker

- Phomopsis spp. canker

v. Excessive seed predation*

The seeds of butternut are highly desired by small mammals, birds and other seed predators but these animals are essential to butternut survival because they aid in the dispersal of seeds. However, if predator populations are unnaturally augmented (e.g. in urban and agricultural landscapes), the regeneration of butternut may be compromised. For example, common grackles (Quiscalus quiscula) are reported to destroy immature fruit (Rink 1990) and often have elevated populations in urban and agricultural landscapes (Graber and Graber 1963, Emlen 1974). The nut is also retailed by humans to some extent, in the Montreal area, as a commodity rich in unsaturated fat. The impacts of seed predation are thought to have minimal effect on the survival of butternut and this threat is only speculative at this point.

vi. Hybridization with exotic Juglans species*

Hybridization with exotic Juglans species is a potential threat for butternut and has been confirmed in the southern and eastern U.S. throughout its native range (Ostry unpubl. data). Of the species with which butternut can hybridize, none occur naturally within Canada. However, several of these species have been planted for nut production or landscaping and hybridized successfully with butternut. For example, a hybrid form with heartnut (Juglans ailantifolia Carrière var. cordiformis) produces buartnut (Millikan et al.1991); with Japanese walnut (J. ailantifolia Carrière) produces J. x bixbyi; and with English walnut (J. regia L.) produces J. x quadrangulata. Butternut has also successfully hybridized with little walnut (J. microcarpa Berl.) and Manchurian walnut (J. mandschurica Maxim.) (Rink 1990). How pervasive hybridization is in butternut’s Canadian range is unknown.

1.6 Actions already completed or underway

New Brunswick. A butternut conservation strategy was developed by the New Brunswick Gene Conservation Working Group (Nielsen et al. 2003). The Working Group identified knowledge gaps and set goals to identify and locate butternut populations in the province; assess the frequency of canker infection and estimate mortality; develop ex situ storage methods, and examine the genetic diversity of butternut and check for the presence of hybrids. They have already successfully cryopreserved

Ontario. The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources initiated a butternut conservation project for southern Ontario in 1994 that included such activities as reviewing the scientific literature, conducting field inventories, documenting populations, grafting scions

Quebec. In 1994 the Canadian Forest Service and the Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune assessed the genetic variability of butternut, researched the biology of the pathogen and tried to establish an in situ and ex situ conservation strategy (Innes 1997). Seeds were collected at several sites throughout Quebec and were planted at a nursery in Berthier. The following year the canker was observed on one-year-old seedlings. This was the first mention of the disease at a nursery – the seedlings were apparently contaminated by infected nuts through the scar at the point of attachment of nut to stem. All the seedlings were given a thorough inspection to eliminate all those with symptoms of the disease. In spring 1996, butternut seedlings that appeared to be free of the disease were planted at four plantations in Quebec, three of them outside the natural range of the species and a fourth inside the range. Annual inspections completed in the first and second year after planting revealed 4% and 3.1% infection of seedlings, respectively. Seedling production was stopped following these observations to avoid spreading the pathogen. The Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune then experimented with a variety of techniques for decontaminating the nuts. Some have proven effective, but improvements are needed (Rainville et al. 2001). A project to inventory and assess the health of butternut on federal lands, led by Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) with participation from Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, the Department of National Defence, National Capital Commission (Gatineau Park )and several aboriginal communities, is now nearing completion, with identification of the last diseased butternut samples that were submitted. NRCan’s Canadian Forest Service in Quebec City is training government and civil society stakeholders in butternut assessment and protection. Outreach documents and online information are available to the general public in both official languages (http://exoticpests.gc.ca/present_eng.asp [link inactive]; http://exoticpests.gc.ca/present_fra.asp)[link inactive].

1.7 Knowledge gaps

In all provinces, information is still required to assess the distribution and abundance of butternut itself, the disease incidence and severity, and to identify putatively resistant trees. Data collection and management should be standardized to facilitate inter-jurisdictional cooperation and comparisons, by following the common protocol developed by specialists with NRCan’s Canadian Forest Service forestry centers and with the natural resource departments of Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick in February 2007. The network of Conservation Data Centres currently in place can play a major role; however, more detailed databases that hold disease assessment and monitoring information are also required. Knowing whether or not resistance to butternut canker exists, and if indeed it does, the mechanisms of resistance (e.g. genetic (G), environmental (E), and/or both (GxE), are also crucial elements necessary for recovery success. Many questions pertinent to long-term butternut survival (e.g. what are ecologically functioning population levels?) remain unknown.

2. Recovery

2.1 Rationale for recovery feasibility

Based on the following four criteria outlined by the Government of Canada (2009), there are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the butternut. At present, it is unknown if trees exist in Canada which are resistant to the butternut canker, yet this information is key to the recovery of this species and will be important in determining recovery feasibility over the long term for butternut. Therefore, in keeping with the precautionary principle, this recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA, as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible. This recovery strategy addresses the unknowns surrounding the feasibility of recovery.

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance. Yes

- Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration. Yes

- The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated. Unknown

- Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe. Unknown

As individuals and habitat are still plentiful for butternut across its range, the recovery of butternut will largely depend on the identification of a canker-resistant strain of the species, from either Canada or the United States, the conservation of genetic material, and a program to restore a viable population that can fulfill butternut’s ecological function

2.2 Long-term recovery goal (> 20 years)

The long-term recovery goal (>20 years) for butternut is to ensure conditions that will allow for the restoration of viable, ecologically functioning, and broadly distributed populations within its current range in Canada.

Butternut populations may not be currently viable due to high rates of infection and mortality caused by the butternut canker. Restoration of viable populations requires the presence of disease-free butternut stands or trees. At present, the conditions required to achieve and ensure disease-free populations are unknown. Thus it is not possible at this time to further quantify the recovery goal or population and distribution objectives.

2.3 Short-term objectives

The short-term objectives are:

- By 2011, develop stewardship and outreach products informing Canadians of the identification, conservation status, conservation mechanisms and management of butternut and on the identification, assessment and management of butternut canker.

- By 2012, collect information on the distribution, abundance and status of butternut and its health across its range in Canada and make it available in a National Database Management System (that is compatible with existing regional Conservation Data Centres).

- By 2014, identify local populations of butternut across its native range and maintain them through focused stewardship in order to increase the likelihood of finding individuals which show resistance to the canker (due to environmental or genetic factors, or a combination thereof).

- By 2014, where the disease is widespread, select, graft and archive at least ten putatively resistant trees in each ecodistrict

footnote x in support of a future breeding and/or vegetative propagation program to produce resistant trees for restoration, and in support of future critical habitat identification. - By 2019, address priority knowledge gaps and research necessary for implementing recovery activities (including research into disease resistance and level of adaptive genetic variation, as well as environmental factors that limit the spread of the disease).

2.4 Approaches recommended to meet recovery goals and objectives

2.4.1. Broad strategies over the short and long term

There is no question that many uncertainties exist surrounding the extent of butternut canker and the species' ability to resist the disease. Although full scientific certainty of many of these questions may never be achieved, the approaches listed within this strategy should assist in the recovery of the species. Some measures should be set in place immediately with the understanding that the broad strategy is dynamic and that the results of monitoring, management and research will continually supply information for ongoing development of the recovery strategy.

Further details of strategies and approaches that should be taken to address threats and achieve goals and objectives are outlined in Table 2. These approaches include both short and long term items with set priorities to help guide action planning for this species.

Table 2. Strategies and approaches to meeting long term recovery goals (>20 yrs) and short term recovery objectives.

| Priority | Objective No. | Broad Strategy to Recovery | Threat(s) addressed | General Description of Research and Management Approaches | Anticipated Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 2 | Inventory and monitoring | Butternut canker |

|

|

| High | 1, 3 | Stewardship / Communication / Outreach | Harvesting Habitat loss and degradation |

|

|

| High | 4 | Inventory (Locate putatively disease resistant materials) | Butternut canker |

|

|

| High | 5 | Research (Canker resistance through genetics) | Butternut canker, Hybridization |

|

|

| High | 5 | Research (Environmental research related to canker resistance | Butternut canker |

|

|

| High | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Gene conservation (Strategic propagation to help maintain gene pool) | Butternut canker |

|

|

| Medium | 5 | Research (Integrated pest management) | Butternut canker |

|

|

| Medium | 5 | Research (knowledge required for long- term survival) | All |

|

|

| Medium | 3 | Policy/legislation improvements | Harvesting, Habitat loss and degradation |

|

|

| Low | 5 | Research | Seed predation and Hybridization |

|

|

2.5 Performance measures

Performance measures for evaluating success in meeting the stated recovery objectives include the extent to which each objective has been met, using the measurable targets detailed in Table 3.

Table 3. Performance measures of short term recovery objectives.

| Recovery Objective | Performance measure |

|---|---|

| 1. By 2011, develop stewardship and outreach products informing Canadians of the identification, conservation status, conservation mechanisms and management of butternut and on the identification, assessment and management of butternut canker. |

|

| 2. By 2012, collect information on the distribution, abundance and status of butternut and its health across its range in Canada and make it available in a National Database Management System (that is compatible with existing regional Conservation Data Centres). |

|

| 3. By 2014, identify local populations of butternut across its native range and maintain them through focused stewardship in order to increase the likelihood of finding individuals which show resistance to the canker (due to environmental or genetic factors, or a combination thereof). |

|

| 4. By 2014, where the disease is widespread, select, graft and archive at least ten putatively resistant trees in each ecodistrict in support of a future breeding and/or vegetative propagation program to produce resistant trees for restoration, and in support of future critical habitat identification. |

|

| 5. By 2019, address priority knowledge gaps and research necessary for implementing recovery activities (including research into disease resistance and level of adaptive genetic variation, as well as environmental factors that limit the spread of the disease). |

|

2.6 Critical habitat

2.6.1 Identification of the species' critical habitat

Butternut presents a unique challenge in terms of the identification of critical habitat for several reasons, largely relating to the fact that this species is wide-ranging and diseased. Firstly, compared to the canker, habitat-related issues are not considered significant threats to butternut survival as presented in the COSEWIC status report (Nielsen et al. 2003). This means that unless resistant trees exist, the species' extirpation from Canada may still occur despite conserving as much butternut habitat as possible. Secondly, although diseased, butternut is currently relatively abundant and widespread throughout its range. Habitat loss and degradation and/or conversion of habitat for alternate land uses are considered a concern for parts of the butternut’s range only. Thirdly, the recovery of butternut depends on resistance to the butternut canker. The mechanisms of resistance are unknown at this time, making the habitat needed to support or facilitate resistance difficult to identify. These factors, combined with the fact that there is not a clear understanding at the population level of what is needed to recover the species, indicate that there is currently not sufficient information to identify critical habitat.

Studies required to prove there is indeed resistance within butternut populations to the butternut canker and to determine if there are habitat features or environmental conditions that contribute to or support resistance will require several years to complete. In the interim, if putative resistance is apparent at a population level at a specific site, the site may be considered for the identification of critical habitat.

2.6.2 Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

The following activities are required before critical habitat can be identified for butternut. An Action Plan with input from each jurisdiction will guide the main activities in this Schedule and ensure consistency across jurisdictions. The disease is not equally impacting each region and, therefore, involvement in critical habitat activities will vary between regions. For example, where the disease is more widespread (e.g. Ontario), Recovery Implementation Groups will try to locate and identify non-diseased and vigorously growing diseased trees, whereas in other areas where the disease is not widespread (e.g. New Brunswick), health/putative resistance to the disease can not be assessed. Due to the unpredictable nature of research and complex nature of the disease, a window of 10 years for completing activities 3-5 in the Schedule of Studies is recommended. As the Action Plan for the butternut will be posted prior to the completion of the schedule of studies it will be updated when critical habitat can be identified.

Table 4. Schedule of studies: Research activities for the identification of critical habitat of butternut in Canada.

| Activity # | Detailed Description of Research Activity (2007-2019) | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stratify butternut populations by province and ecodistrict, using a coordinated approach |

Ongoing |

| 2 | In ecodistricts where the disease is widespread, identify a minimum of 10 putatively resistant, healthy trees and monitor trees to determine if environment (site) contributes to resistance. | 2014 |

| 3 | Develop a method to test putative resistance (e.g. through inoculation of the fungus to seedlings or grafted material), while considering the potential interaction of genetic and environmental conditions in resistance. | 2019 |

| 4 | Test material from the 10 putatively resistant individuals per ecodistrict for disease resistance. | 2019 |

| 5 | If resistance is proven, identify areas where resistant trees are found as critical habitat. | 2019 |

2.7 Effects on other species

The conservation of butternut in situ will have positive effects and support the diversity of species using butternut, its habitat and its other ecological functions (as yet undefined). As a result, this strategy will contribute to Canada’s commitment to conserve biodiversity under the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy. Negative consequences to other species, natural communities or ecological processes are expected to be minimal. For example, forest management techniques geared toward higher light conditions may have a negative impact for species requiring less light. Adverse effects from such forest management approaches are not suspected to be significant since butternut is typically scattered throughout a forest and efforts to increase light will be relatively small and localized.

2.8 Recommended approach to recovery implementation

The Recovery Strategy and Action Plan must follow the adaptive-management approach, whereby new information feeds back into the plan on a regular basis in order to respond to new tools, knowledge, challenges, and opportunities. Wherever possible, recovery actions recommended in this strategy should be considered in the development of management plans by agencies and organizations that own and manage land on which the species resides. The Regional Recovery Implementation Groups should be consulted prior to undertaking activities that may affect occupied butternut habitat.