Chief Medical Officer of Health 2024 Annual Report

Protecting Tomorrow: The Future of Immunization in Ontario

Dedication

This report is dedicated to Ontarians, and to the health care workers, local public health partners and community leaders whose unwavering commitment to providing immunizations to their communities has saved the lives of many.

Land acknowledgement

Contributors to this report respectfully acknowledge that the lands on which this work was developed are the traditional and enduring homelands of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples, who have cared for and stewarded these territories since time immemorial. Specifically, this report was prepared in the following traditional territories:

- In Toronto, also known as Tkaronto, the traditional territory of many nations, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnaabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples. Toronto is covered by Treaty 13 with the Mississaugas of the Credit and is now home to many diverse urban First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples. Toronto is within the lands protected by the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Haudenosaunee and Anishnaabeg and allied nations to peaceably share and care for the resources around the Great Lakes.

- In Ottawa, also known as Adawe, on the traditional unceded and unsurrendered territory of the Algonquin People, members of the Anishnabek Nation Governance Agreement.

- In London, on the traditional lands of the Anishnaabek, Haudenosaunee, Lūnaapéewak and Chonnonton Nations, on lands connected with London Township and Sombra Treaties of 1796 and the Dish with One Spoon Covenant Wampum.

- In Hamilton, on the traditional territories of the Mississauga and Haudenosaunee nations, and within the lands protected by the Dish with One Spoon Wampum agreement.

- In Durham Region, on the traditional territory of the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation, covered under the Williams Treaties, and the traditional lands of the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Huron-Wendat peoples.

We understand that land acknowledgements alone are not enough. We recognize that our presence on these lands comes with responsibilities, not only to the people of these lands, but to the land itself. This acknowledgement comes with a commitment to ongoing learning, care for the land and support for Indigenous leadership in stewardship and decision making. We also recognize that stewardship is not ownership, it is a shared responsibility rooted in respect, humility, and accountability. We recognize colonial structures, including public health spaces, continue to produce inequities, and we are committed to working together to ameliorate these disparities and improve the health of all Ontarians. We are guided by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis partners in shaping health equity strategies, prioritizing Indigenous ways of knowing and being, and fostering Indigenous health in Indigenous hands.

Letter from Dr. Moore

Dear Mr. Speaker,

I am pleased to share with you my 2024 Annual Report, “Protecting Tomorrow: The Future of Immunization in Ontario,” in fulfillment of the requirements of the independent Chief Medical Officer of Health for Ontario, and as outlined in section 81(4) of the Health Protection and Promotion Act, 1990.

This report celebrates the profound and lasting impact of immunization in Ontario. It highlights the leadership and dedication of policymakers and clinicians who have worked tirelessly to dramatically reduce or eliminate the spread of once-devastating diseases, like smallpox, polio, and rubella.

Protecting Tomorrow demonstrates the vital role provincial investment has played in increasing access to immunization. By expanding the number of registered health care providers, including pharmacists and midwives, who can administer vaccines, and in strengthening connections with primary care, more Ontarians can now receive timely immunizations. Additionally, new digital tools are starting to give people easy access to their health records which will enable people to track their vaccinations, as well as those of their children and family members.

To ensure continued progress on the investments made to date, Ontario must address remaining gaps in its immunization system. The absence of a centralized immunization information system makes it challenging to identify and respond to coverage gaps across the province.

While routine vaccines have saved the lives of thousands of children, access remains uneven in some communities. At the same time, misinformation and vaccine fatigue continue to erode public trust in the safety and importance of immunization. Tackling these issues head-on will strengthen Ontario’s ability to protect all residents from preventable diseases today and in the years to come.

Strong relationships between health care providers and communities must be at the heart of Ontario’s immunization strategy. I dedicate much of the report to highlighting the success of community-led initiatives because we know this is how trust is built.

This report presents a practical and forward-looking vision for Ontario’s immunization system – one that includes a centralized provincial immunization information system, broader access to life-saving vaccines, enhanced surveillance, greater public confidence in vaccination and sustained investment in preparedness and innovation.

I wish to extend my deepest thanks and appreciation to those who contributed to this report, including the External Advisory Committee and internal review teams at the Ontario Ministry of Health.

Yours truly,

Dr. Kieran Moore

Executive summary

The power and promise of immunization

Immunization is one of the most effective public health interventions in history. Globally, vaccines prevent up to 5 million deaths each year. In Ontario, immunization has helped eliminate diseases like polio and rubella, and drastically reduced others such as whooping cough. Beyond saving lives, vaccines also deliver major economic benefits. Adult immunizations alone save Canada an estimated $2.5 billion each year in decreased healthcare costs and productivity gains.

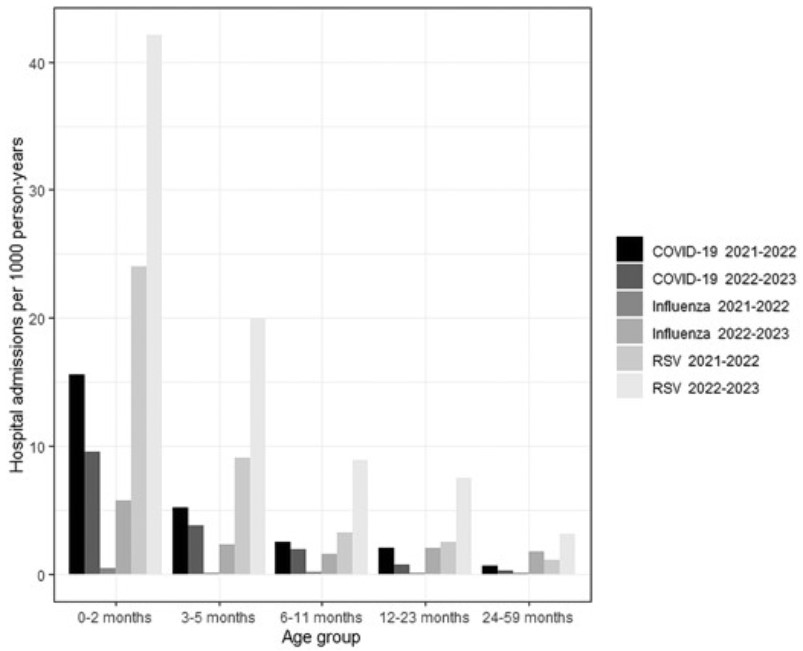

Ontario’s immunization programs have expanded significantly over the years, now covering 29 vaccines that protect against 23 diseases. Since 2014, public investment in these programs has grown by over 400%. New additions include Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) vaccines for infants and high-risk seniors, and broader pneumococcal protection for children and older adults. These developments highlight the growing recognition of immunization as a vital tool, not only in preventing infectious disease and cancer but also in managing chronic conditions.

Investments in prevention

Provincial investments have played a vital role in expanding access to immunization across the province. By expanding the number of registered health care providers, such as pharmacists and midwives, who can administer vaccines and through strengthening connections to primary care, more Ontarians can now receive timely immunizations. Additionally, new digital tools that give people easy access to their health records will offer convenience and the opportunity to improve access to their immunization history.

Preparing for the future

To ensure continued progress, Ontario must address remaining gaps in its immunization system. The absence of a centralized immunization information system makes it extremely challenging to identify and respond to coverage gaps across the province. Although routine vaccines have saved the lives of thousands of children, access remains uneven in some communities. At the same time, misinformation and vaccine fatigue continue to erode public trust in the safety and importance of immunization. Tackling these issues head-on will strengthen Ontario’s ability to protect all residents from preventable diseases today and in the years to come.

Protecting tomorrow

To strengthen Ontario’s immunization programs for the future, this year’s report outlines a practical, achievable vision.

A province-wide digital immunization information system would consolidate records, enable real-time monitoring, and support improved outbreak response. It would also link to sociodemographic data to identify and address access issues.

Relationships in the community must be at the heart of Ontario’s immunization strategy. Community-led initiatives like the mpox Awareness Campaign, the Black Scientists’ Task Force Town Halls, and the Na-Me-Res Vaccine Pow Wow show how culturally informed, locally driven approaches can build trust and improve access.

Strengthening vaccine confidence is equally critical. Healthcare providers remain the most trusted source of vaccine information and ensuring they have access to the best available resources is essential to increasing public confidence. A centralized Immunization Resource Centre would support both providers and the public with accurate, accessible information. Community ambassadors, trusted messengers within their own communities, can also play a powerful role in countering misinformation.

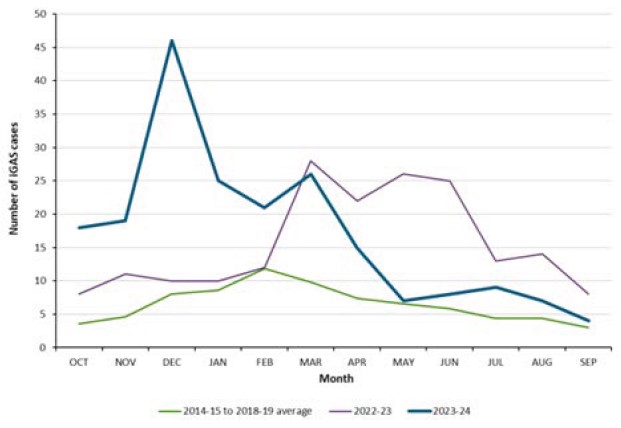

Ontario must also be ready for emerging threats – from outbreaks of infectious diseases, such as measles, to future pandemics. This means investing in domestic vaccine development and manufacturing, and supporting innovations to tackle antimicrobial resistance and prevent cancer.

Key recommendations:

- Build a centralized provincial immunization information system to make it easier for people to check their immunization history.

- Advocate for a national immunization information system and harmonized vaccine schedule to ensure consistency and equity across Canada.

- Address inconsistencies in access by supporting community-led strategies and improving access to primary care.

- Strengthen vaccine confidence through trusted relationships with healthcare providers and community ambassadors.

- Strengthen surveillance systems to monitor vaccine safety and effectiveness in real time.

- Invest in innovation and preparedness, including domestic vaccine development and manufacturing; using new technologies to tackle emerging threats.

Section 1. Introduction

Immunization saves lives

Immunization is one of the most effective public health interventions in history. It prevents the spread of infectious disease, reduces infant mortality and has increased life expectancy on a global scale.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 3.5 - 5 million lives are saved each year through routine immunizations alone which prevent diseases like diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, influenza and measles.

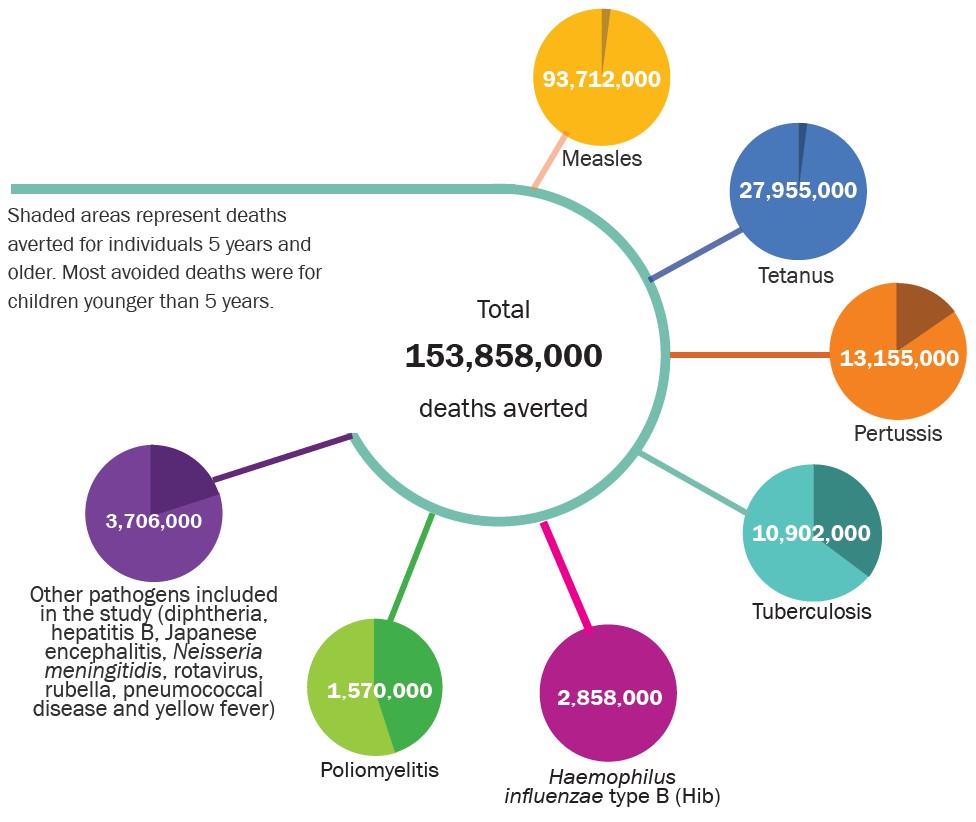

Figure 1. Total number of deaths averted globally due to vaccines, 1974-2024

Source: Adapted from Shattock AJ, Johnson HC, Sim SY, et al. Contribution of vaccination to improved survival and health: modelling 50 years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. The Lancet. 2024;403(10441):2307-2316.

Immunizations have made many once-feared diseases preventable and, in one case, eradicated. In 1967, WHO announced a vaccination program to eradicate smallpox, a disease which caused death, disfigurement and blindness. Thanks to a global effort, smallpox was eradicated in 1980, marking a historic public health achievement. While smallpox is the only disease that has been eradicated on a global scale, immunization has led to the elimination of diseases like polio, endemic measles, and rubella in Canada.

Universal immunization programs have also drastically reduced the incidence of diseases like whooping cough, mumps, measles, diphtheria and rubella in Canada.

| Disease | Cases before the introduction of vaccine* | Cases after the introduction of vaccine** | Percent reduction in cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whooping Cough (Pertussis) | 17,777 | 2,340 | 87% |

| Mumps | 36,101 | 737 | 98% |

| Measles | 53,584 | 37 | 99% |

| Diphtheria | 8,142 | 5 | 99% |

| Rubella | 14,974 | 1 | 99% |

| Polio | 2,545 | 0 | 100% |

*Cases before the introduction of vaccine are average annual case counts in Canada during the five years before routine vaccine or closest possible five years where stable reporting was occurring.

**Cases after the introduction of the vaccine is the average annual case count in Canada 2016-2020. Canada has held endemic measles elimination status since 1998. Given global circulation, outbreaks still occur in Canada because of imported cases.

Source: ©All rights reserved. Vaccines Work: Case counts of 6 vaccine-preventable diseases before and after routine vaccination. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2023. Reproduced with permission from the Minister of Health. 2025.

An investment in prevention

In addition to reducing morbidity and mortality, immunization is also a significant source of cost savings for the health care system, reducing emergency room visits, hospitalizations and intensive care unit admissions.

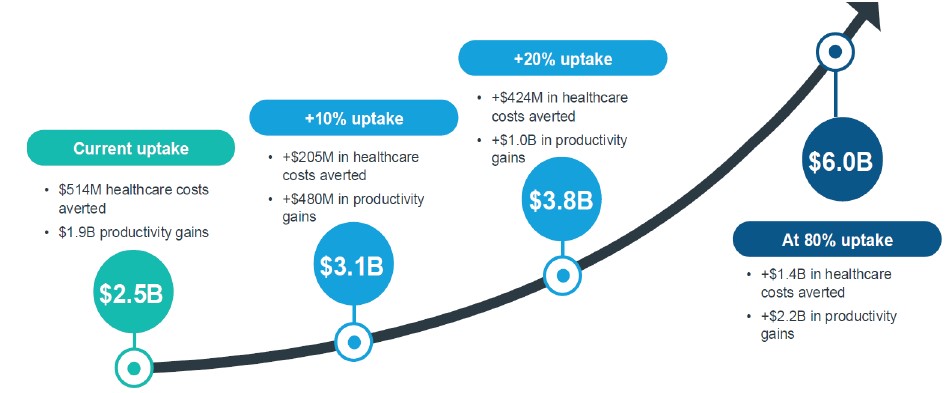

A recent report commissioned by the Adult Vaccine Alliance and 19 to Zero estimates that in Canada adult vaccines result in cost savings of $2.5 billion annually, including $514 million in health care savings and $1.9 billion in economic benefits.

Figure 3. Value of adult vaccines in Canada

| $514M Value to the healthcare system | $1.9B Value to the economy | $2.5B Estimated annual value | 341% Overall value of vaccines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult vaccines are estimated to generate $514M in savings for the healthcare system, of which $410M are from hospitalization costs averted. | The productivity benefits to the national economy associated with adult vaccines. | Estimated annual value of adult vaccines in Canada including value to the healthcare system and the economy. | Every dollar invested in adult vaccines returns more than three times its value in healthcare costs averted and productivity gains, on average. |

Source: IQVIA Solutions. The Unmet Value of Vaccines in Canada - IQVIA Study. Adult Vaccine Alliance; 2024.

Still, immunization holds the potential for even greater cost savings if more people receive vaccinations. Increasing adult uptake of the shingles, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), pneumococcal, Human Papillomavirus (HPV), COVID-19 and influenza (flu) vaccines by even 20% could add $1 billion in productivity gains nationally.

Figure 4. Increases in the uptake of adult vaccines would lead to economic and health care savings

Source: IQVIA Solutions. The Unmet Value of Vaccines in Canada - IQVIA Study. Adult Vaccine Alliance; 2024.

Section 2. Current immunization landscape in Ontario

Ontario’s publicly funded immunization programs

Immunizations protect against life-threatening infectious diseases across the lifespan, including those that can lead to cancer and other serious complications. They also play a critical role in the management of chronic diseases by preventing serious complications and secondary infections.

With projections showing that 1 in 4 Ontarians will be diagnosed with a chronic disease by 2040

Investment in immunization

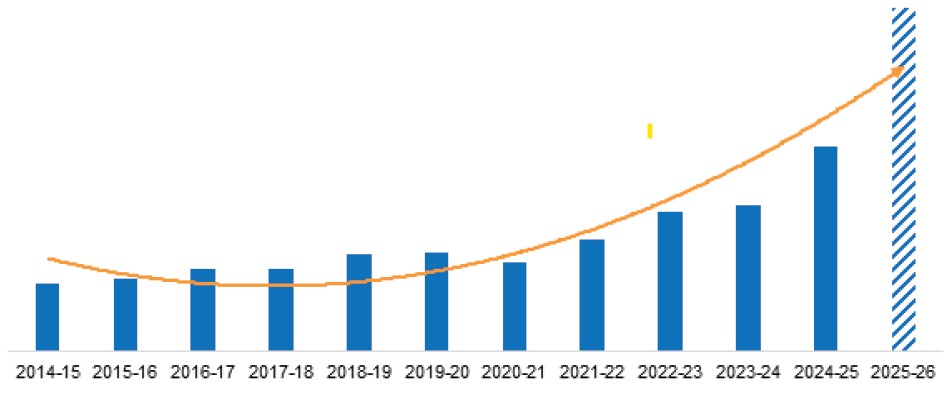

Ontario’s publicly funded immunization programs have expanded in scope in recent years to include 29 unique immunization products which protect against 23 different diseases. Between 2014 and 2025, investment in publicly funded immunization in Ontario has increased by over 400% (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Ontario immunization programs: Year over year spending, 2014-2025

Source: Ministry of Health, 2025

Since 2023, Ontario has introduced new vaccines to better protect people at higher risk from serious illnesses such as:

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | Invasive Pneumococcal Disease (IPD) |

|---|---|

High-risk older adult program, introduced fall/ winter 2023-24 Universal infant program, introduced fall/winter 2024-25 | Prevnar 15 (for children and high- risk adults) and Prevnar 20 (for seniors) vaccines, introduced summer 2024 |

For over a decade, Ontario has led the way in early childhood immunization programs. In 2011, Ontario was one of the first jurisdictions in Canada to offer the rotavirus vaccine to all infants. Then in September 2024, Ontario became one of only three provinces to offer the RSV vaccine to all infants.

Continued investment in research and new vaccine technologies will help create more ways to protect people from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Spotlight: A national harmonized immunization schedule in Canada

Since 1997, the Canadian Paediatric Society has advocated for a harmonized immunization schedule.

This patchwork approach can lead to confusion when families move between provinces, increasing the risk of missed or delayed vaccinations. It also raises an equity issue, as children in some regions may receive critical vaccines later, or not at all, compared to others.

Beyond improving access and consistency, a national schedule could offer economic advantages. Centralized procurement by the federal government would likely reduce costs through bulk purchasing, compared to separate provincial agreements. With Canada’s National Pharmacare Strategy already in development, the infrastructure to support coordinated federal vaccine purchasing is already taking shape.

Figure 6. Immunizations across the lifespan in Ontario

Pregnancy

Vaccines to protect against tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, influenza, and COVID-19 are offered during pregnancy to protect newborns in the first few months of life.

Children

Vaccines that protect against 12 serious infections, including diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, Hib, pneumococcal disease, RSV and rotavirus are offered at well-child visits.

Adolescents

Grade 7 students are offered HPV, hepatitis B, and meningitis vaccines through school-based clinics.

Seniors

Vaccines for pneumococcal disease and shingles are offered to seniors and beginning in 2023, RSV is offered for high-risk seniors.

Seasonal vaccines

Flu and COVID-19 vaccines are available to everyone, but they are especially important for people at high risk of developing severe illness like seniors and those living in long term care settings.

Immunization legislation and workplace requirements

The Immunization of School Pupils Act (ISPA) requires students to submit proof of vaccination against nine diseases or have a valid exemption.

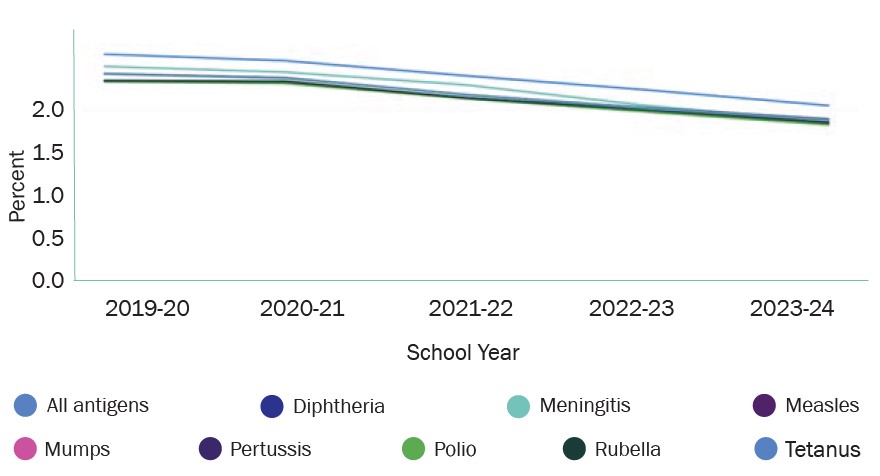

Valid exemptions permitted under the ISPA fall into two categories: medical exemptions (contraindication or prior immunity) and non-medical exemptions (conscience or religious belief). The percentage of children with non-medical exemptions in Ontario has remained stable since 2019 at 2%.

Figure 7. Non-medical exemptions for selected antigens among 17 year olds in Ontario, 2019-2020 to 2023-24 school year

Source: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Non-medical exemptions for selected antigens in Ontario. 2025.

The Child Care and Early Years Act (CCEYA) mandates proof of immunization for child care enrollment against disease specified by the local Medical Officer of Health.

Workplace policies require vaccines for child care operators, emergency medical attendants, and paramedics to keep these settings safe from infectious diseases.

Figure 8. How vaccines are given in Ontario

In Ontario, many health care providers offer vaccines to help make them easily accessible.

Routine childhood vaccines

Given by family doctors and pediatricians during regular checkups (well-child visits).

School-based vaccines

Public health nurses give vaccines to Grade 7 students at school clinics.

Public health units also run catch-up clinics for students who are behind on routine immunizations.

Vaccines during pregnancy

Pregnant people get vaccines like Tdap, flu, RSV, and COVID-19 from midwives, obstetricians and family doctors.

Hospital staff vaccines

Hospital physicians, nurses and pharmacists give vaccines to staff to meet workplace health policies.

Emergency vaccines

Emergency departments give vaccines for rabies or tetanus after possible exposure.

Flu and COVID-19 vaccines

Mostly given by pharmacists in the community, with some also provided by family doctors.

Immunizations during disease outbreaks or pandemics

Public health units coordinate mass immunization clinics with health system partners to provide access to immunization in emergency or outbreak scenarios.

Figure 9. Ontario’s publicly-funded immunization schedule

These vaccines are free for eligible individuals as part of Ontario’s publicly funded immunization program.

| Pregnancy |

|

|---|---|

| Newborn |

|

| 2 months |

|

| 4 months |

|

| 6 months |

|

| 12 months |

|

| 15 months |

|

| 18 months |

|

| 4-6 years |

|

| Grade 7 |

|

| 14-16 years |

|

| 18-64 years |

|

| 65 years & older |

|

Adapted from: Ministry of Health. Immunization through the lifespan. 2024.

Spotlight on MMR: Early childhood immunization

Measles, mumps, and rubella are serious diseases which can cause severe complications, especially in young children. Measles can lead to pneumonia, encephalitis and meningitis, while rubella, if contracted during pregnancy, can cause miscarriage, stillbirth and severe birth defects. To protect against these diseases, the MMR vaccine is given to children after 12 months, with a second dose using MMRV (with addition of chickenpox antigen) at four to six years to provide protection across the lifespan.

The vaccine is highly effective: nearly 100% for measles, 95% for mumps, and 97% for rubella after two doses following the immunization schedule. High vaccine coverage is crucial because measles is highly contagious, with a 90% infection rate among those without immunity. Even small gaps in coverage within the population can lead to outbreaks.

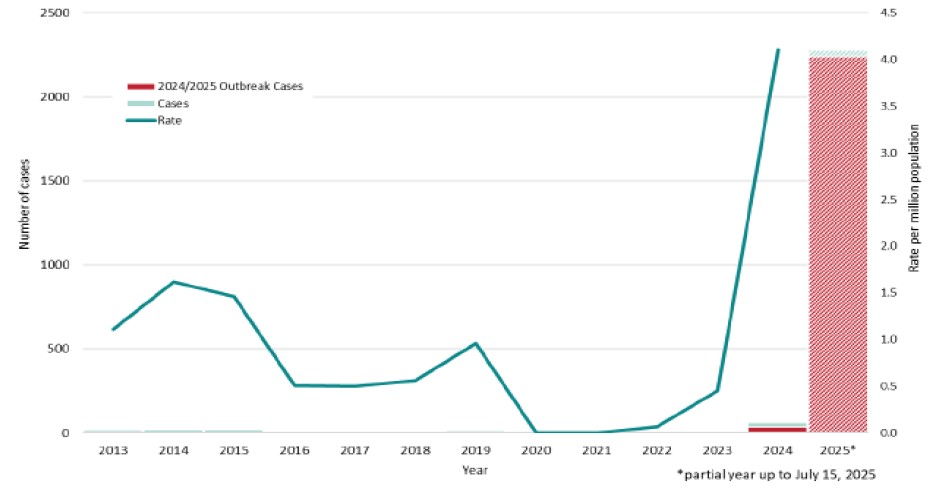

Ontario’s measles outbreak 2024-25

In October 2024, Ontario began its largest measles outbreak in nearly thirty years with transmission primarily occurring within pockets of unimmunized communities. As of July 2, 2025, this multi-jurisdictional outbreak originating from a travel-related case has resulted in 2,223 cases, 150 hospitalizations and 12 ICU admissions in Ontario since the start of the outbreak. Recent epidemiological data as of July 2025 indicate that cases counts have stabilized in Ontario.

Source: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Measles in Ontario. Toronto, ON: King’s Printer for Ontario; 2025.

Twenty-six public health units have been affected by the outbreak with the majority of cases occurring in western Ontario. Given the effectiveness of the vaccine in preventing disease, the vast majority of measles cases associated with the outbreak have occurred among those who are unimmunized or who have unknown immunization status.

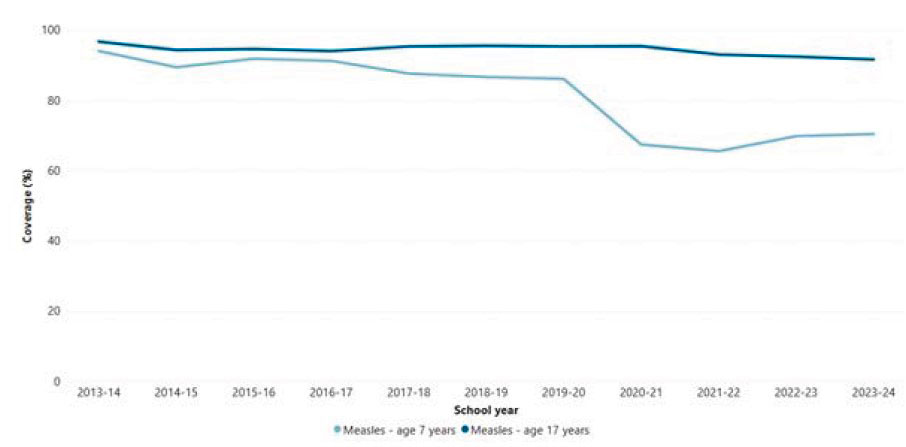

Given the very high transmissibility of the measles virus, an immunization coverage rate of at least 95% at the population level is recommended to prevent outbreaks. In Ontario, disruptions to the delivery of primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in decreases in coverage. Although delays in immunization coverage assessment may underestimate true coverage rates, currently available data indicates that measles immunization coverage among seven-year-olds fell from 86% in 2019-20 to 70% in 2023-24 in Ontario.

Figure 11. Measles immunization coverage in Ontario 2013-14 to 2023-24

Source: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Immunization Data Tool. Public Health Ontario. 2025.

The measles outbreak in Ontario has taken a significant toll on families, communities, emergency departments, hospitals, and intensive care units. Local public health authorities continue to play a pivotal role in outbreak response - conducting case and contact management investigations, reporting and running catch-up immunization clinics.

Spotlight on HPV vaccine: Adolescent immunization

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is transmitted through intimate contact and an estimated 80% of individuals will be infected with HPV in their lifetime. Strains of HPV can cause genital warts while others can lead to cancers including cervical, throat, penile and anal cancers. Vaccination before exposure is crucial for cancer prevention.

In Ontario, the rate of oropharynx cancers increased by 13% annually between 1993 and 2010, a finding that is linked to the rise in HPV infections seen in Canada, the United States and Europe.

Virtually all cases of cervical cancer are caused by persistent HPV infections, and therefore are almost entirely preventable through a combination of immunization and early screening. While cervical cancers can be treated if detected early, treatment is invasive and costly. Vaccination before exposure provides 90% protection from cervical cancer and can prevent more invasive procedures.

Figure 12. The cost of primary and secondary prevention compared to treatment of invasive cervical cancer

| Primary prevention | Treatment of invasive cancer |

|---|---|

HPV Immunization - $200 per dose

| $79,500 for five years of treatment

|

Expanding cervical cancer screening and HPV immunization has lowered the number of cervical cancer cases in Canada. However, it remains the third most common cancer among women aged 20-40 with 400 deaths in Canada each year.

Spotlight on pneumococcal: Immunization for seniors

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a common cause of respiratory infections like pneumonia and ear infections. It can also lead to more severe infections of the blood (bacteremia) or brain (meningitis), which are known as invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD). There are routine and high-risk immunization programs to protect those most at-risk for IPD, which includes seniors and adults with underlying medical conditions that predispose them to severe outcomes.

The introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine program for seniors (aged 65 years and older) and high-risk individuals in 1996 reduced IPD infections by 49%.

As of July 2024, Ontario introduced a new vaccine Prevnar20 for seniors and high-risk individuals. This vaccine provides broader and longer-term protection. This update follows Health Canada approval and NACI recommendations examining the burden of pneumococcal disease in older adults.

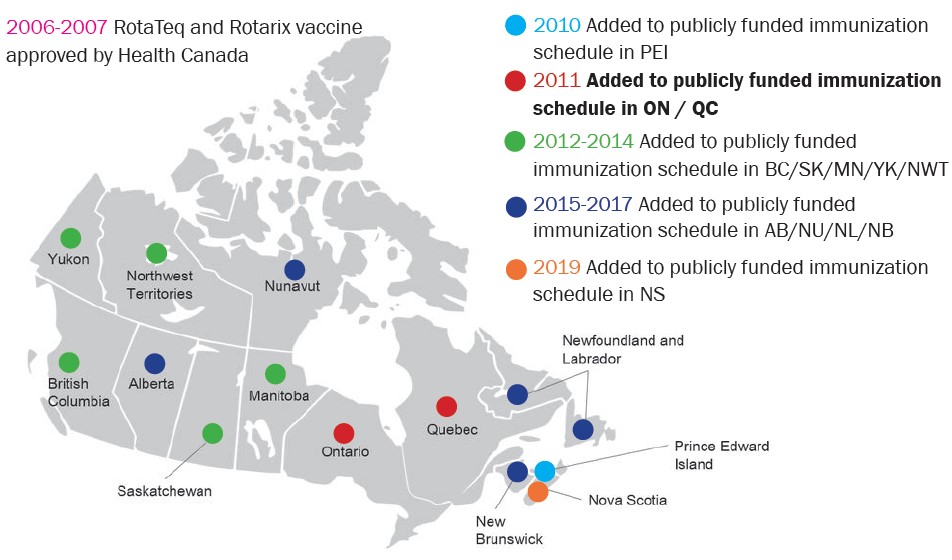

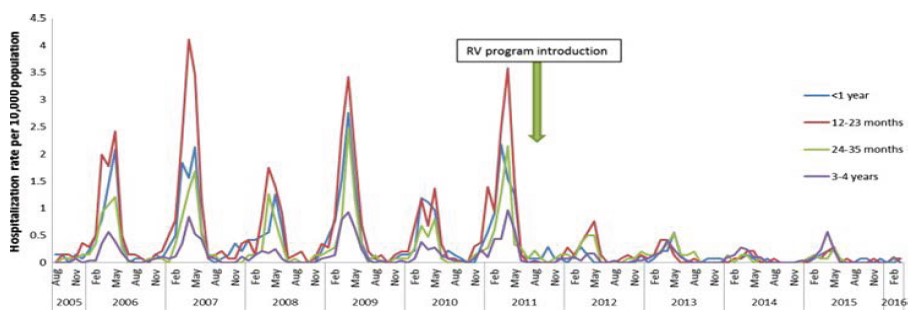

Spotlight on rotavirus: An Ontario success story

Rotavirus is a common infectious disease that causes gastrointestinal symptoms in children. Before vaccines, most children were infected by the age of five. While infections are usually mild in healthy children, they can cause severe dehydration and death in immunocompromised children. In Canada, two vaccines, RotaTeq and Rotarix, have been approved by Health Canada.

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommended these vaccines for healthy infants in 2008 and 2010 respectively, but their addition to publicly funded immunization schedules was staggered across provinces and territories (see Figure 13).

Figure 13. Rotavirus immunization implementation in Canada 2008-2019

In August 2011, Ontario became the second province in Canada to publicly fund the rotavirus vaccine. Before the vaccine, rotavirus infections were highest among children one to two years, and severe outcomes requiring hospitalization were disproportionality experienced by children living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Source: Wilson SE, Rosella LC, Wang J, et al. Equity and impact: Ontario’s infant rotavirus immunization program five years following implementation. A population-based cohort study. Vaccine. 2019;37(17):2408-2414.

Section 3. Current challenges

Despite these successes, Ontario faces challenges that could increase health inequities, reduce vaccination rates and put more pressure on the health care system if not addressed.

To ensure all Ontarians can live longer, healthier lives and receive the full benefit of immunization, three central issues must be addressed:

- 1Gaps in immunization data

- 2Disparities in access and uptake

- 3Declining vaccine confidence

Resolving gaps in immunization data

Immunization data in Ontario are spread across multiple record systems, making it difficult to check if individuals are up to date, to provide efficient clinical services and to determine vaccination coverage for communities and regions. The lack of a comprehensive, province-wide immunization data system presents several challenges including:

For patients and families

- Confusion about vaccine eligibility and prior immunizations;

- Inconvenience of a paper-based immunization record (“yellow card”);

- Difficulty in tracking and communicating vaccine history and adverse reactions to multiple providers, increasing the risk of errors in vaccination and gaps in protection; and

- Challenges in providing proof of vaccination for school, work, travel, or relocation.

For health care providers

- Difficulty accessing patients’ comprehensive immunization history, increasing the potential for errors or inadequate protection; and

- Inability to efficiently assess practice- level vaccine coverage in real-time to make infection prevention and control decisions for patients.

For public health

- Lack the tools to conduct systematic real-time immunization coverage assessment of people living in Ontario (like during the COVID-19 pandemic which guided the response and provided reassurance of protection);

- Inability to detect and monitor inequities in vaccine access among sociodemographic groups;

- Relying on periodic national surveys and public health assessments to estimate vaccine coverage;

- Difficulty in assessing community risk and planning targeted interventions to improve equitable vaccine uptake;

- Complicates assessments of vaccine effectiveness and the ongoing monitoring of safety due to the lack of a unified information system linked to primary care, hospital and laboratory data; and

- Reliance on parents or providers to report immunizations, which is neither timely nor comprehensive.

For health care system

- Duplicate or missed vaccinations due to multiple record systems;

- Inefficient use of time as providers and patients piece together immunization records from various sources;

- Safety concerns if information related to contraindications or previous adverse reactions are not communicated to all health care providers within the individual’s circle of care; and

- Product wastage due to challenges in inventory assessment.

Addressing disparities in access and uptake

Disparities are driven by structural and systemic factors that create barriers to vaccine access as well as beliefs and attitudes that can impact confidence.

- Contextual factors may prevent attendance at immunization appointments, e.g., work, transportation, or childcare issues.

footnote 15 Mobility issuesfootnote 16 and language barriers also impede access and uptake.footnote 17 - Historical and ongoing discrimination within health care settings and more broadly in society can also impact attitudes towards immunization. Black and Indigenous communities face intergenerational trauma and mistrust of institutions due to stigma and mistreatment.

footnote 18 ,footnote 19 2SLGBTQIA+ communities may fear misgendering or emotional violence in health care settings leading to medical mistrust.footnote 20 This mistrust can lower vaccine uptake and widen health inequities.footnote 21

The 2021 childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey, conducted by the Public Health Agency of Canada, reported lower immunization coverage for routine early childhood immunizations among

- Children identifying as Black;

- Children living in remote areas;

- Children living in households with lower household income; and

- Children living in households with a parent or guardian with lower educational attainment.

Ontario does not have consistent data to track vaccine uptake among different sociodemographic groups, making it challenging to identify and address gaps.

National surveys and local data suggest that some groups in Ontario face greater barriers to vaccination, leading to unfair differences in health outcomes.

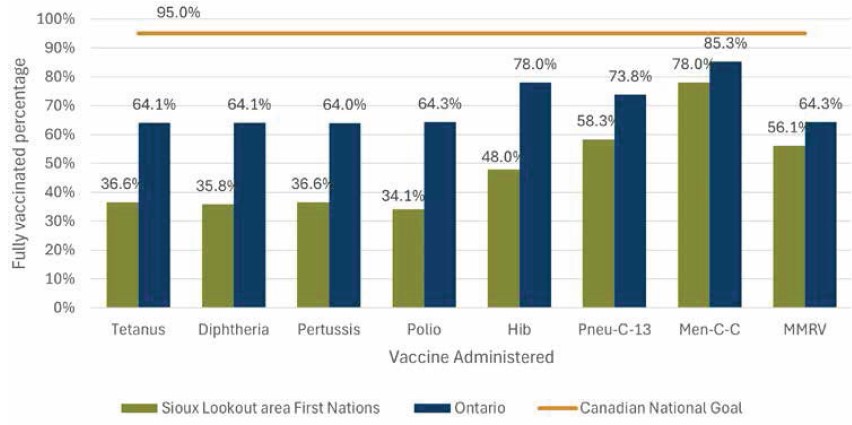

For example, childhood immunization coverage among seven-year-old children in Sioux Lookout First Nation Health Authority was found to be substantially lower compared to coverage in the rest of Ontario

Figure 15. Immunization coverage among seven-year-olds by type of vaccine, 2024

Source: ©Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority (SLFNHA), 2024. Reproduced with permission.

Reversing declining vaccine confidence

Vaccine confidence is a critical component to vaccine uptake.

In 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO warned about the pressing global threat of vaccine hesitancy.

Decrease in vaccine confidence

Key concerns:

- Parental confidence: Only 67% of Canadian parents in 2024 would vaccinate their children without hesitation, down from 88% in 2019.

footnote 26 - Skepticism and side effects: 29% are skeptical about vaccine science, and 34% worry about side effects.

footnote 26 - Economic impact: Misinformation delayed COVID-19 vaccine uptake for 2.3 million Canadians, costing the health care system $300 million in 2021.

footnote 27

Figure 16. Vaccine attitudes among Canadian parents with children under age 18

2019

2024

Blue - I'm not sure

Purple - I would vaccinate without reservation

Red - I'm really against vaccinating my children

Source: Angus Reid Institute. Parental Opposition to Childhood Vaccination Grows as Canadians Worry about Harms of Anti-Vax Movement, 2024.

Vaccine fatigue

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in vaccine fatigue, defined as “inaction towards vaccine information due to perceived burden or burnout”.

Figure 17. Vaccine fatigue reported by Canadians, August 2023

54% of Canadians have moderate to very high vaccine fatigue

Very high fatigue

High fatigue

Moderate fatigue

Low fatigue

I am not fatigued when it comes to vaccines

Source: Canadian Pharmacists Association. Canadians’ level of vaccine fatigue has pharmacists worried heading into cold and flu season – English 2023.

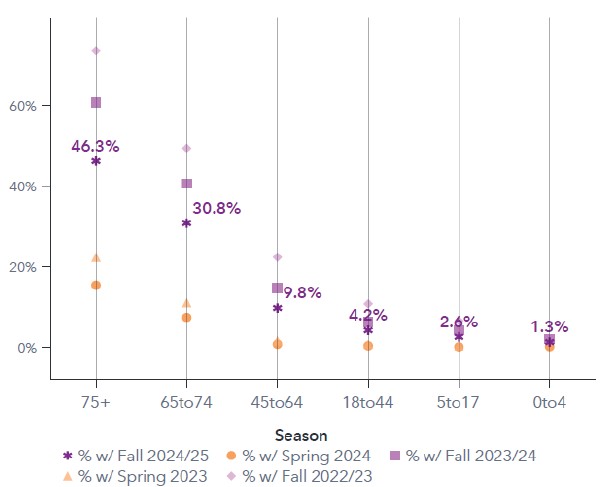

Seasonal vaccines, which require annual or biannual boosters to maintain protection, are particularly likely to be impacted by vaccine fatigue.

In Ontario, the impact of vaccine fatigue is increasingly evident in the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, even among seniors. In 2022, 73.7% of people aged 75 and older received a COVID-19 vaccine compared to only 46.3% in Fall 2024.

Figure 18. Seasonal COVID-19 immunization coverage by age in Ontario, 2022-2025

Source: Ministry of Health. Seasonal COVID-19 immunization coverage by age in Ontario, 2022-2025.

Section 4. Strengthening Ontario’s immunization programs

Figure 19. One immunization record for all Ontarians

- Up-to-date protection: Ensures up-to-date immunizations throughout lifespan, with reminders for annual and routine vaccines.

- Comprehensive records: Allows individuals to accurately monitor their vaccination history across their lifespan.

- Accessibility: Easy submission of vaccination records for school, work, and travel.

- Health management: Facilitates better health management and proactive healthcare decisions.

- Public health: Enhances public health efforts by ensuring high immunization coverage and timely outbreak response.

A vision for the future of immunization in Ontario

Vaccination programs should be based on an efficient, comprehensive immunization information system that captures all immunizations from all providers across the lifespan. This interconnected provincial immunization information system would provide real-time data to everyone, including patients and health care providers, significantly improving vaccine program monitoring and evaluation. The vision for the future includes:

Digital immunization records:

- Every Ontarian would have a single digital record of all their immunizations, whether publicly funded or privately purchased, linked to their digital medical record.

- This record would be accessible to both the individual/family and their health care providers.

- People would be automatically informed if they are up-to-date and when they are eligible to receive their next immunization.

Comprehensive data:

- The record would include information about each vaccine dose, such as product details, any adverse reactions, contraindications, consent and exemptions.

- Compatibility across systems will allow data collection from all providers, including electronic medical records, hospital records and systems from other provinces to allow for seamless information sharing.

- All vaccinators will be required to enter immunization records into the information system.

Unique identifier:

- Each person’s unique immunization record will be linked with other provincial health data, such as clinical care, hospital and ICU records, ensuring integration across the health system and across the patient’s circle of care.

Enhanced monitoring and surveillance:

- The linked data will allow public health authorities to better monitor vaccine effectiveness, immunization coverage, safety, and program performance.

- Immunization linked to sociodemographic data will allow detection and monitoring of inequities in vaccine uptake, informing strategies to improve access and confidence.

- Mandatory data entry of all vaccines administered will ensure every individual’s immunization record was complete and up to date.

The vision for a national immunization information system in Canada

For over 20 years, individuals, families, health care providers and public health experts have emphasized the need for a national immunization data system. This system would improve tracking of vaccine coverage and facilitate record transfers across provinces and territories. It would also support monitoring of disease prevalence, vaccine effectiveness and safety at the national level.

The Public Health Agency of Canada is working with provinces and territories on a proof-of-concept to connect immunization registries and improve data access. The goal is to enable individual record portability across jurisdictions, creating comprehensive records for public health assessment to ensure people across Canada are protected, regardless of where in the country they live.

Lessons from SARS

- The 2003 SARS outbreak highlighted the need for a unified public health surveillance system to manage national responses to disease outbreaks.

- The National Advisory Committee on SARS recommended a national system to track immunizations in real- time.

Panorama system

- The Federal Government funded Canada Health Infoway to work with federal, provincial and territorial partners on the implementation of Panorama, a public health surveillance system that is used in many provinces and territories.

- Despite this, comprehensive and standardized data collection and interoperability between provincial systems have remained a challenge.

Interoperability efforts

- In 2020, the Pan- Canadian Health Data Strategy Expert Group recommended common principles for health data use, sharing, and management to enhance system compatibility.

- Federal, provincial, and territorial (FPT) governments committed to developing standardized health data policies and tools.

Recent investments

- The 2023 Federal budget included nearly $200 billion over ten years to modernize health care, including standardized health data and digital tools.

- The FPT Action Plan on Health Data and Digital Health, signed by all provincial and territorial Ministers of Health, was announced in October 2023 to improve health data management and transparency.

Enabling a national harmonized immunization schedule

- A national immunization information system would enable a national harmonized immunization schedule for all Canadians, enhancing equity in access across jurisdictions.

- A Canada-wide immunization schedule would facilitate greater efficiencies in vaccine procurement including bulk purchasing, domestic production, and risk-managed contracts.

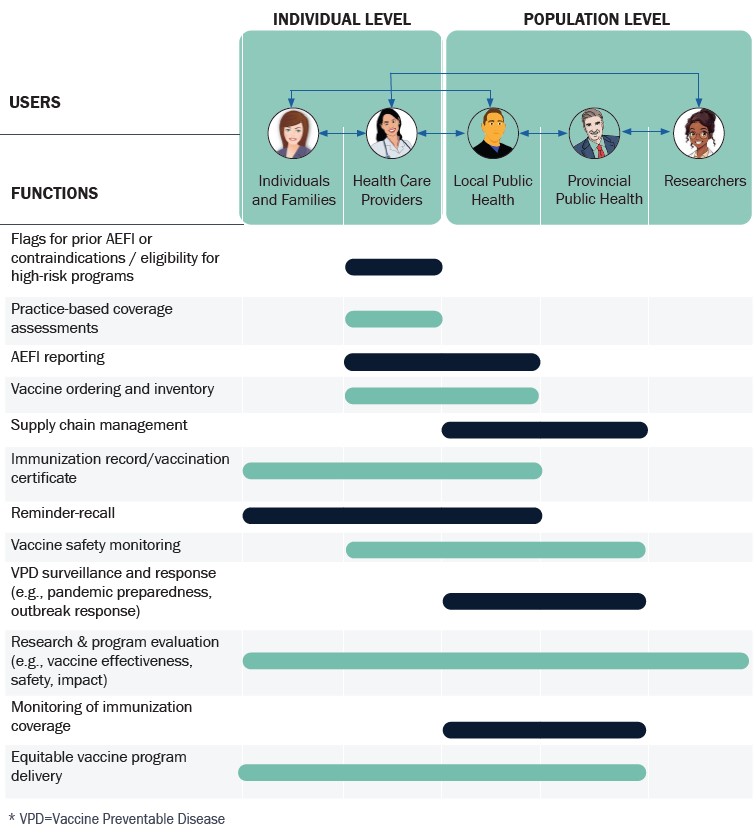

Addressing challenge #1: Resolving gaps in immunization data

Modern immunization programs require comprehensive immunization data registries.

As investment in publicly funded immunization programs continues to grow in Ontario, a comprehensive immunization information system is needed to ensure Ontarians have access to their own health information, providers have the information to inform clinical services, and public health resources are managed efficiently and effectively.

Currently in Ontario there are three separate places where immunization data is kept:

- 1Panorama:

For school and childcare immunizations.

- 2COVaxON:

For COVID-19 immunizations.

- 3Administrative datasets:

Includes Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) billing claims and electronic medical records for immunizations administered in physician offices or community pharmacies.

Ontario’s disparate immunization records system presents significant data access issues:

- Immunization coverage is assessed in different places. (i.e., through Panorama for school-age children and COVaxON for COVID-19 vaccines).

- Reporting by health care providers and parents is not mandatory, leading to incomplete records in Panorama.

- There are significant time lags and high administrative burden for public health authorities in assessing vaccine coverage.

- Adult immunizations are recorded in electronic medical records, which are not centralized, or only available as OHIP billing claims for immunizations administered in pharmacies

- There is no mechanism to assess coverage for adult non-COVID-19 immunizations.

Currently, Ontario lags behind other provinces like British Columbia, Quebec, Alberta, Manitoba and Nova Scotia, who continue to expand their digital solutions for immunization records.

A recent position statement by the Ontario Immunization Advisory Committee (OIAC) reinforced the pressing need for a central immunization information system to improve the delivery of Ontario’s immunization programs and ensure more efficient use of health care resources.

Because the province does not have a central repository for all immunization data across a person’s lifespan, individuals (and parents/caregivers) must take on the role of central record keepers.

The 2022 Office of the Auditor General of Ontario report highlighted that the lack of a centralized COVID-19 immunization information system early in the pandemic hindered coverage assessment and equity monitoring, leading to some high-risk groups being overlooked.

Figure 20. Characteristics of Ontario’s current immunization data systems

| Characteristic | Digital health immunization repository (Panorama) | COVID-19 immunization registry (COVaxON) | Administrative data (e.g., OHIP provider billing data) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Programs Captured |

|

|

|

| Reminder - Recall |

|

|

|

| Access to Immunization Records |

|

|

|

| Entry of Immunization Records |

|

|

|

| Data Elements & Terminology |

|

|

|

| Support for Vaccine Programs |

|

|

|

| Monitoring and Evaluation |

|

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

|

Adapted from: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario), Ontario Immunization Advisory Committee. Position Statement: A Provincial Immunization Registry for Ontario.; 2024.

Implementing a provincial immunization information system

Benefits for people living in Ontario include:

Easy access:

Provide individuals/families with on-demand immunization data for school, work, travel, or relocation.

System efficiency:

Allow for better vaccine inventory management and distribution, minimizing wastage and maximizing effectiveness of the provincial investment in immunization. Enhances supply chain efficiency, optimizing health care spending.

Reminders:

Reminders to ensure immunizations are not missed to support optimized protection.

Enhanced evidence:

Support vaccine program performance monitoring, including safety and effectiveness and duration of protection.

Streamlined care:

Help health care providers access full immunization records, improving clinical care and avoiding unnecessary revaccination and invalid schedules.

Improved confidence:

Provide precise information on vaccine effectiveness and safety, so Ontarians can feel confident regarding vaccine safety.

Better monitoring:

Improve vaccine coverage monitoring and identified unimmunized individuals, especially during outbreaks, ensuring we build community immunity against common diseases. Detect rare safety signals earlier, improving outcomes.

Addressing disparities:

Identify gaps in vaccine coverage by region and sociodemographic groups, allowing for tailored interventions.

Balancing user benefit and privacy

While the benefits are significant, privacy and data access must be carefully managed. A provincial immunization information system needs clear data governance guidelines to regulate who can access immunization data and when.

These frameworks must specify how the data will be used and how to ensure privacy and confidentiality are protected.

Using sociodemographic data to detect gaps in vaccine coverage

Identifying and monitoring differences in health care access is a critical first step to addressing disparities. Without reliable and timely data to detect and track differences in vaccine uptake by sociodemographic groups at a population level, it is difficult to design, implement or evaluate interventions that promote access and reduce gaps in coverage. The collection of sociodemographic data linked to health data for the purpose of identifying disparities is an approach supported by both The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) and the Anti-Racism Directorate.

Spotlight: High priority communities strategy

The High-Priority Communities Strategy supported 15 high-needs communities in Ontario, including Durham, Peel, Toronto, York and Ottawa, which were identified due to COVID-19 infection rates, low testing rates and barriers to testing or self-isolation. The strategy funded local agencies to work with Ontario Health and community partners to deliver key interventions.

Actions included door-to-door outreach by community ambassadors, culturally appropriate communications, increased testing locations with transportation assistance, and wraparound supports like groceries and emergency financial assistance. This approach enhanced service awareness, countered misinformation and addressed barriers to testing and self-isolation.

Previous outbreaks, such as the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, revealed significant disparities in disease outcomes. In Manitoba, First Nations children experienced infection rates five times higher and the rate of hospitalization was 22 times higher than non-First Nations children.

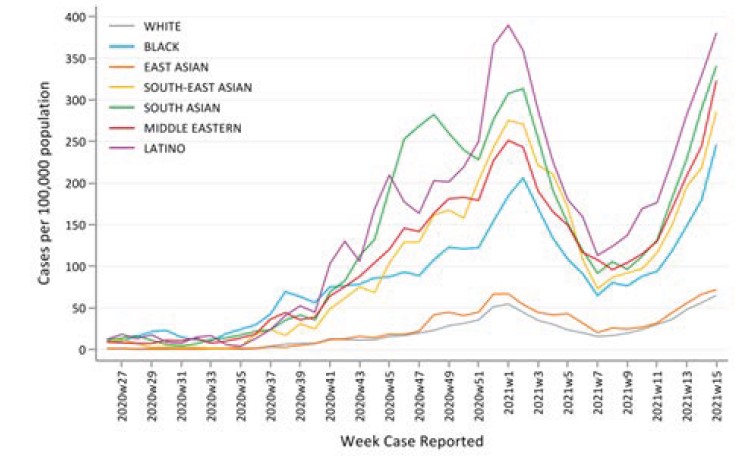

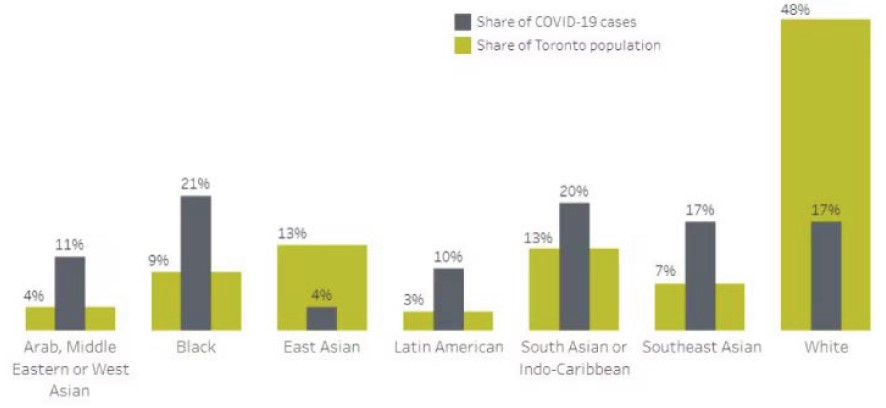

During the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in April 2020, public health units in Peel, Middlesex-London and Toronto started collecting sociodemographic data among those who tested positive for COVID-19. By June 2020, this was required by the province through the Health Protection and Promotion Act, Despite challenges in getting complete data, it was evident that COVID-19 infection rates were 4.6, 7.1, and 6.7 times higher among Black, Latino and South Asian Ontarians, respectively, compared to white Ontarians.

Figure 21. Weekly COVID-19 case counts per capita by race in Ontario (June 2020-April 2021)

Source: McKenzie K, Dube S, Petersen S, Equity, Inclusion, Diversity and Anti-Racism Team, Ontario Health. Tracking COVID-19 through Race-Based Data. Ontario Health, Wellesley Institute; 2025.

Local public health units used data on infection rates among specific populations to focus efforts on those at highest risk of COVID-19. Toronto Public Health found that Black Torontonians and other non-white populations made up 83% of all COVID-19 infections but only 50% of the population of Toronto. Households with five or more people were also overrepresented among those infected. The availability of this data led to targeted testing, improved community communication and increased social support.

Figure 22. COVID-19 cases among ethno-racial groups compared to the share of people living in Toronto, with valid date up to July 16th, 2020

Source: COVID-19: Ethno-racial identity & income. City of Toronto. 2021.

Voluntary collection of sociodemographic data for people receiving the COVID-19 vaccine at vaccination sites began in March 2021. The goal was to support the development and delivery of an equitable vaccination strategy.

Nonetheless, survey data, such as the Canadian Community Health Survey (2021-22), indicated higher rates of non-vaccination among off-reserve First Nations and Black people compared to white Canadians.

Surveys help but are time-consuming and results are delayed, hindering real-time evaluation and intervention. A provincial immunization information system and improved data collection would enable ongoing monitoring and improve access.

Considerations in the collection Of race-based data

The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC), the Wellesley Institute and the Black Health Alliance have called on the health care system and all levels of government to strengthen their capacity to collect and use race-based data for the purpose of improving equity and promoting health.

Effective health equity monitoring initiatives must be implemented carefully. They require clear communication about data collection goals, addressing community concerns and building trust. There must be transparency, privacy and the option to opt-in or to opt-out, as per the Anti-Racism Act, 2017.

Indigenous data sovereignty and adherence to specific data principles such as Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) for First Nations, Ownership, Control, Access and Stewardship (OCAS) for Métis and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) for Inuit are important components of data governance.

Figure 23. Benefits of an immunization information system for Ontario

| Benefits of an immunization information system for different stakeholders | |

|---|---|

Individuals/families

| Healthcare system

|

Healthcare providers

| Public health

|

*AEFI=Adverse Event Following Immunization

Adapted from: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario), Ontario Immunization Advisory Committee. Position Statement: A Provincial Immunization Registry for Ontario. 2024.

Ontario has faced challenges in implementing a comprehensive immunization information system due to its complex public health system and numerous immunizers. Integrating data from various health care providers without duplicating entries has been difficult. The Ministry of Health is currently working on information technology solutions leveraging Panorama to improve data linkages and surveillance. Current efforts, such as integrating electronic medical records to enhance access, are encouraging. The end goal must be an accessible, comprehensive provincial immunization data system.

Spotlight on CoVaxON (Ontario’s COVID-19 vaccination information system)

During the pandemic, CoVaxON was created to securely capture data on all COVID-19 vaccines administered in Ontario. The data system mandated by The COVID-19 Vaccination Reporting Act, 2021, allowed Ontarians to access their immunization records online and receive reminders.

CoVaxON enabled surveillance of vaccine coverage, effectiveness, and safety, helping to prioritize immunization delivery. Access to comprehensive immunization data also enabled the identification of rare adverse events, leading to preferential vaccine and dosing recommendations.

This system demonstrates the benefits and functionality of a comprehensive, secure, web-based provincial immunization information system. However, despite its benefits, the system’s lack of integration with electronic medical records led to duplicative data entry which was a burden to health care providers. Future systems must eliminate this to gain health care provider support.

Adapted from: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario), Ontario Immunization Advisory Committee. Position Statement: A Provincial Immunization Registry for Ontario. 2024.

Addressing challenge #2: Addressing disparities in access and uptake

Using a needs-based framework to guide immunization programs

Health inequities are systematic differences in opportunities for groups to achieve optimal health, leading to unfair and avoidable differences in health outcomes.

Differences in access and uptake of immunization make certain groups more vulnerable to infectious and chronic diseases, leading to poorer health outcomes in the short and long term.

Recognizing the need to address equity issues in immunization programs, NACI has adopted the Ethics, Equity, Feasibility and Acceptability Framework. This framework provides tools to evaluate and assess programs with a needs-based focus, leading to more transparent and evidence-based policy decisions.

Building trust and empowering community leadership

Differences in immunization uptake can be driven by access barriers (e.g., transportation, language barriers) or distrust of institutions due to past negative experiences accessing health care or social services.

To rebuild confidence among underserved groups, including 2SLGBTQIA+, people experiencing homelessness, refugees and asylum seekers, and racialized communities, it is crucial to engage with the community and involve members in designing and planning immunization campaigns.

Spotlight: Black health plan

In 2020, COVID-19 infection rates among Black Torontonians were over nine times higher than white Torontonians. Reasons for this disparity included exacerbation of existing health inequities and social factors which both increased the risk of infection and undermined the impact of public health strategies on Black populations.

In response, The Black Health Plan Working Group was formed in 2020, followed several months later by the Black Scientists Table.

Additionally, The Black Physicians of Ontario, Black Health Alliance, community health centres, and community groups focused their work on the pandemic response.

Together they advocated for the collection of sociodemographic data in collaboration with Ontario's High Priority Community Strategy. They developed strategies to reduce infection, including community vaccination clinics and over 20 town hall events reaching over 6,000 people to build trust and counter misinformation.

Building on this work, Ontario published its first Black Health Plan in 2023, with recommendations to improve vaccine uptake, address hesitancy and enhance access through community initiatives and race-based data collection.

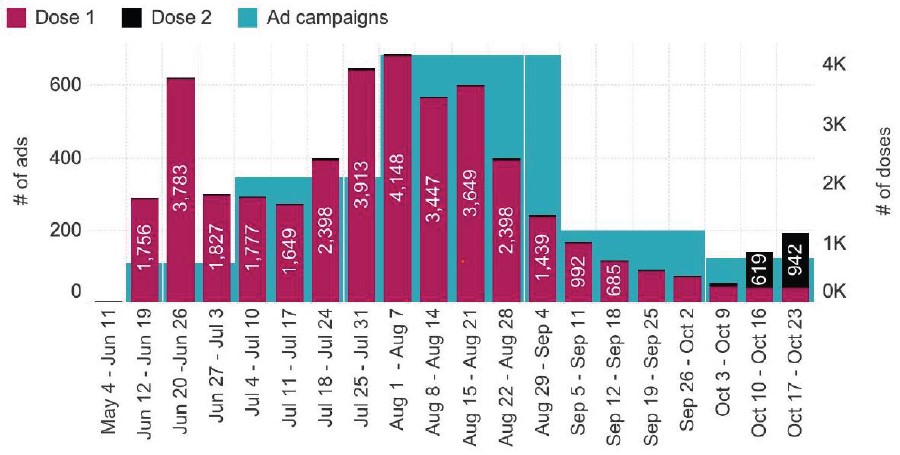

During the mpox outbreaks in Ontario, partnerships with community agencies led to the development of a highly successful community-informed immunization campaign. As Figure 26 shows, vaccine uptake was closely aligned with the number of social media posts deployed each week, demonstrating the effectiveness of awareness campaigns in increasing demand for vaccination. After a steep increase of mpox cases from May to August 2022, cases plateaued in the Fall due to vaccine uptake and changes in behaviour.

Spotlight: Ontario’s mpox awareness campaign

Mpox cases were first identified in Europe in April 2022 and by May 2022, Ontario declared an outbreak. Men who have sex with men (MSM) were at higher risk. Due to the history of stigmatizing public health responses towards 2SLGBTQIA+ populations, an effective community- led strategy was essential to success.

The Gay Men’s Sexual Health Alliance (GMSH) was key to the mpox response. Partnerships between GMSH, the Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health and community agencies were pivotal to the program's success. GMSH provided sexual health promotion expertise and advised on health and vaccine promotion strategies through weekly meetings.

Figure 25. Mpox awareness campaign

Source: Tan DHS, Awad A, Zygmunt A, et al. Community Mobilization to Guide the Public Health Response During the 2022 Ontario Mpox Outbreak: A Brief Report. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 024;11(Supplement_2):S129-S132.

A multi-lingual awareness campaign on mpox symptoms and prevention, including immunization, was launched. The social media campaign, which was accessed over 74 million times, used a sex-positive approach and candid language to communicate key public health messages.

COVID-19 mass immunization clinics were expanded for the administration of mpox vaccines. Between May and October 2022, a total of 37,470 doses of mpox vaccines were administered in Ontario.

In this example, community expertise successfully guided vaccine policy and planning. Local public health also worked with community leaders to set up pop-up vaccine clinics.

Figure 26. Timeline of social media ad campaigns compared to vaccination trends in Ontario

Source: Ismail Y, Zapotoczny V. Ontario’s Mpox Awareness Campaign Evaluation: Final Report. Gay Men’s Sexual Health Alliance; 2023.

Identifying the need for community-specific strategies

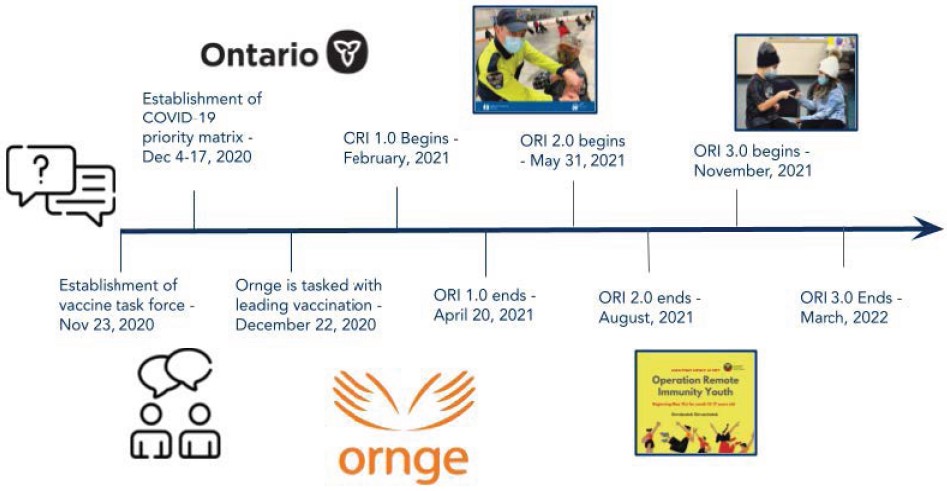

Spotlight: Operation remote immunity

Once COVID-19 vaccines were approved in Canada, distribution became a central priority. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities were prioritized for immunization due to higher risks of severe outcomes from underlying conditions and challenges, such as limited access to clean water or household overcrowding.

In December 2020, Ontario launched Operation Remote Immunity (ORI). Working in collaboration with Indigenous leaders, Ornge - a non-profit organization responsible for critical transport in Ontario - assisted in delivering thousands of vaccine doses to remote communities.

In its first phase, ORI delivered over 25,000 doses to 31 remote First Nations communities and Moosonee. The second phase (ORI 2.0) which began in May 2021 resulted in the administration of nearly 6,000 doses, including boosters. The third phase (ORI 3.0) which began in March 2022, resulted in the delivery of an additional 9,700 doses.

Figure 27. The timeline of Operation Remote Immunity

Source: Burton S, Hartsoe E, Li W, Wang A, Wong J. Operation Remote Immunity. Reach Alliance; 2023.

Most First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people live off-reserve, with many residing in urban areas.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, urban Indigenous communities in Toronto and London had a 20% lower vaccine uptake compared to the general population. Barriers included lack of access to culturally-safe care (defined as health care which recognizes, respects and nurtures the cultural identity of the individual)

Indigenous health centres including Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre (SOAHAC) and Maamwesying North Shore Community Health Services responded by providing culturally-safe health care spaces for COVID-19 and routine immunizations. These centers continue to offer immunizations alongside comprehensive primary care services.

Spotlight: Na-Me-Res vaccine clinic pow wow

Na-Me-Res, an emergency shelter for Indigenous men organized a Vaccine Clinic Pow Wow at University of Toronto’s Varsity Stadium during the COVID-19 pandemic to provide First Nations, Inuit and Métis people with a culturally-safe vaccination site.

The pop-up clinic, which was arranged through a partnership between Waakebiness-Bryce Institute for Indigenous Health at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Well Living House, and Seven Generations Midwives Toronto, vaccinated a total of 200 people while pow wow drummers and dancers performed. The success of this clinic led to the establishment of Auduzhe Mino Nesewinong (“place of healthy breathing”) which operates as an Indigenous Interprofessional Primary Care Team offering culturally-safe primary care services in Toronto.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people face inequities in routine and seasonal vaccine access.

Barriers to access

A recent review found that the second most common barrier to vaccination—after lack of information—was difficulty accessing vaccines

Figure 28. The 3Cs of vaccine hesitancy

- Convenience

- Confidence

- Complacency

Adapted from: MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine.

2015;33(34):4161-4164.

Expanding access to immunization

Ontario’s Plan for Connected and Convenient Care has broadened the range of health care professionals who can administer vaccines.

Midwives

In May 2024, the Ontario government expanded midwives’ scope of practice to allow the administration of vaccines like COVID-19, influenza and Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis).

- Nearly 1 in 5 births in Ontario are attended by midwives.

- Vaccines administered during pregnancy, like Tdap, provide 91-93% protection from pertussis for infants in the first month of life before they can be immunized themselves.

footnote 56 ,footnote 57

Pharmacists

Pharmacists’ scope of practice related to immunization has also expanded in Ontario, providing more opportunities for Ontarians to access a wide range of vaccines in their communities (see Figure 29).

Figure 29. Expanded scope of practice for pharmacists related to immunization in Ontario

2012

Injection-trained pharmacists are authorized to administer the seasonal flu vaccine as part of the Universal Influenza Immunization Program (UIIP) to patients 5 years and older

2020

Injection-trained pharmacists, pharmacy interns and pharmacy students are permitted to administer the flu vaccine to children two years and older and the high-dose influenza vaccine for seniors 65+ through an expansion of the Universal Influenza Immunization Program (UIIP).

2016

Pharmacists’ scope of practice is expanded to include the administration of 12 vaccines to patients 5 years and older. These diseases include:

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B

- Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Japanese Encephalitis

- Meningococcal disease

- Pneumococcal disease

- Rabies

- Typhoid

- Varicella

- Yellow Fever

2021

Injection-trained pharmacists, pharmacy students, interns and pharmacy technicians are authorized to administer COVID-19 vaccines in Ontario

Adapted from: Ontario Pharmacists Association. 10 years of immunizations. 2022.

Primary care and access gaps

In Ontario, routine childhood immunizations are primarily administered by family doctors, unlike in several other provinces where public health nurses play a larger role. This model presents challenges:

- Ontario is currently experiencing a shortage of primary care physicians.

- Individuals and families without a primary care provider may face barriers to accessing routine vaccines.

- A 2009 study found a correlation between the number of family physicians and pediatricians in Ontario and vaccine coverage among seven-year-olds.

footnote 58

Presently, 2.2 million Ontarians are without a primary care provider, including 360,000 children, with newcomers and low-income communities being most affected.

In response, Ontario announced the formation of the Primary Care Action Team (PCAT) led by Dr. Jane Philpott, whose central mandate includes a commitment to connect all Ontarians to a primary care team within four years.

Overcoming barriers

To improve vaccine access, Ontario must adopt flexible community-focused strategies.

- Public awareness campaigns: Especially during respiratory virus season, early and widespread flu vaccine availability is critical for high-risk populations.

- Tailored community approaches: In Northern Ontario, where access to family doctors is limited, some public health units administer routine childhood vaccines directly. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, former mass vaccination sites have also been repurposed to help children catch up on missed immunizations.

- In 2024–25, the Northwestern Health Unit provided 3,379 routine early childhood vaccines.

Community based solutions

Pop-up vaccine clinics at Wellness Fairs hosted by the Peel Black Health and Social Services Hub have demonstrated the effectiveness of community-based approaches:

- These fairs address common barriers like transportation, scheduling issues and fears associated with accessing immunizations in traditional health care settings including stigma or cultural barriers.

- Initially focused on COVID-19 vaccines, they now also offer routine immunizations for school-aged children.

- The Hub is supported by the Black Health Alliance, Black Physicians Association of Ontario, and local partners such as Roots Community Services, Partners Community Health and LAMP Community Health Centre.

These trusted, familiar settings help families catch up on missed vaccines and improve overall access.

Spotlight on: The SickKids Immunization InfoLine

The SickKids Immunization InfoLine is a free, by-appointment phone consultation service that provides expert guidance related to immunizations for children, youth, and those who are pregnant or breastfeeding. The InfoLine offers open one-on-one conversations with a specially- trained nurse. Families can ask questions and get information specific to their child on vaccine eligibility, safety, access and effectiveness in a secure and non-judgmental environment to assist in informed decision-making.

Parents and caregivers that reside in Ontario can book appointments directly through the website and do not require a referral or an OHIP/health card. The InfoLine plays a critical role in system navigation – helping families overcome access issues and find support for vaccine confidence issues, even if they are unattached to a primary care provider. For complex cases where additional consultation is necessary, the service can directly refer children and families to specialists to provide additional guidance. The InfoLine is available in multiple languages using over-the-phone language interpretation to ensure that language barriers are not an obstacle to receiving support.

The service began in 2021, specifically focused on COVID-19 immunizations (previously called “The SickKids COVID-19 Vaccine Consult Service”) but has since expanded to provide support related to all routine immunizations offered during childhood and pregnancy. The consult service is staffed by a nurse with support from paediatric infectious disease physicians and is offered free of charge to all residents of Ontario and their families.

Looking ahead: Strengthening access across Ontario

To ensure lifelong vaccine access for all Ontarians, we must:

- Strengthen connections to family doctors;

- Address local barriers that hinder access; and

- Explore innovative, community-specific solutions that reflect the diverse needs of Ontario’s population.

Spotlight on: Quebec CLSCs

Centres Locaux de Services Communautaires (CLSCs) were established in Quebec in the early 1960s after the Castonguay-Nepveu Commission reforms. There are 147 CLSCs in Quebec, providing routine preventative care including immunizations within an integrated community- based hub. They also offer consultations with primary care physicians, nurse practitioners and allied health professionals.

Social services include social and psychological consultations, crisis response and mental health counseling. CLSCs also provide rehabilitation, chronic disease management and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention.

Addressing challenge #3: Reversing declining vaccine confidence

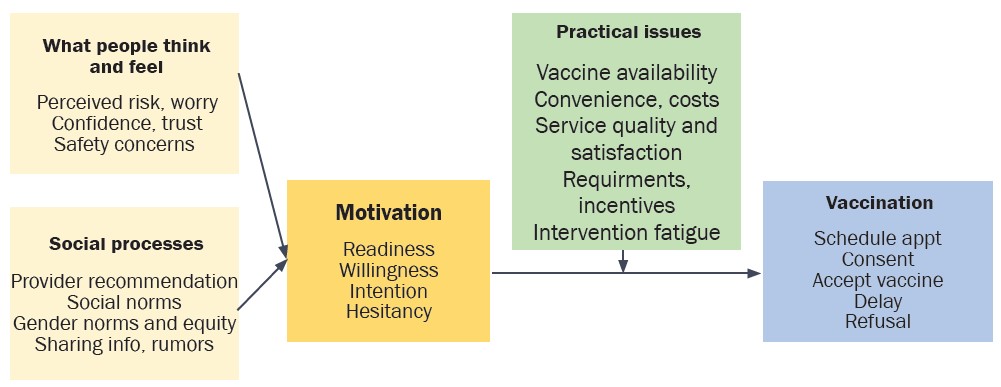

Building vaccine confidence

Attitudes towards vaccination can be impacted by many factors including the context in which a person lives (i.e., geography or culture), personal experiences and attitudes which may differ depending on the vaccine.

In 1998, a flawed (and later retracted) study published in The Lancet by Andrew Wakefield and colleagues falsely linked the MMR vaccine to autism, which reduced vaccine confidence despite overwhelming evidence disproving the claim. This misinformation led to increased measles cases, even in countries where the disease had been eliminated.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a lack of confidence related to mRNA vaccines due to their novelty, despite the availability of data to support their safety and efficacy, was a major driver of hesitancy. Throughout and following the COVID-19 pandemic, social media played a central role in the amplification of myths and misinformation.

Figure 30. Determinants of vaccine hesitancy

| Determinants | Influenced by |

|---|---|

Contextual (e.g., historic, socio- cultural, environmental, health system/institutional, economic, political factors) |

|

Individual and Group (e.g., personal perception or social/peer environment) |

|

Vaccine/Vaccination Specific Issues (e.g., Directly related to vaccine or vaccination) |

|

Adapted from: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Building Confidence in Vaccines, 2021.

Experiences of discrimination or negative interactions with the health care system can reduce trust and affect attitudes towards immunization and health care institutions.

Specific groups, such as those who identify as 2SLGBTQIA+, individuals experiencing homelessness, refugees and asylum seekers, and racialized communities may have experienced stigma or a lack of understanding about their specific health needs within health care settings, leading them to avoid accessing preventative health care services like vaccination.

Social norms and information sources also play a key role in views on vaccine safety, efficacy and necessity.

Figure 31. The behavioural and social drivers of vaccination framework

Source: Gagnon D, Beauchamp F, Bergeron A, Dube E. Vaccine hesitancy in parents: how can we help? CanVax. 2023.

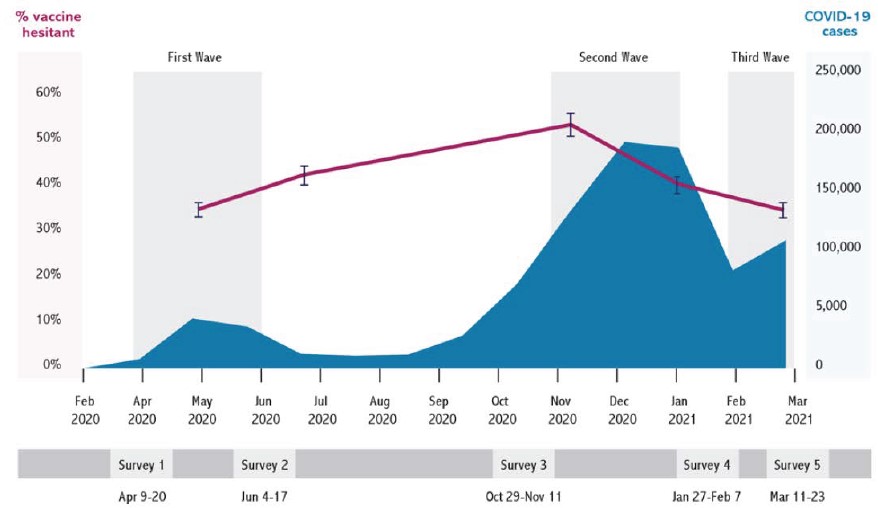

Vaccine confidence changes over time, presenting both challenges and opportunities to improve trust. During the COVID-19 pandemic, self-reported vaccine hesitancy in Canada peaked at 52.9% during the second wave in November 2020, compared to 36.8% in the first wave and 36.9% in the third wave.

Figure 32. Rates of vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada

Source: Lavoie K, Gosselin-Boucher V, Stojanovic J, et al. Understanding national trends in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Canada: results from five sequential cross-sectional representative surveys spanning April 2020–March 2021. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e059411.

Addressing the drivers of vaccine hesitancy

Building vaccine confidence is crucial for high vaccine uptake. Given the complexity of vaccine decision-making, a multi-pronged approach is needed to address various drivers of hesitancy.

Equipping health care providers with the tools to build vaccine confidence

Health care providers are the most trusted source of information about vaccination.

A recommendation from a trusted health care provider is the most powerful way to reduce vaccine hesitancy and encourage people to get vaccinated.

Using a presumptive approach when introducing vaccines.

Telling parents which vaccines their child needs, instead of asking about their plans, leads to more parents agreeing to vaccinate their child.

Employing motivational interviewing techinques.

Motivational interviewing is a proven method for building vaccine confidence, recognized by the WHO.

Providing a strong, personal immunization recommendation.

Recommendation by a health care provider has been found to be effective in increasing vaccine uptake. A strong recommendation by a health care provider (assertive language and personal pronouns) compared to recommendations that used passive language with a reference to institutional recommendations is more effective in increasing vaccine uptake.

Creating supportive health care environments to enhance trust.

Cultural training is essential for those serving priority populations including Indigenous and Black communities who face significant barriers to accessing health care due to racism. Tailored communication strategies that are culturally-informed and attuned to the needs of underserved populations are critical to creating culturally safe health care environments.

Combatting vaccine fatigue.

Clearly articulating the benefits of immunization and the importance of booster doses to maintain protection can help address vaccine fatigue. Persuasive immunization campaigns are one way to communicate these messages; one-on-one conversations with a health care provider about an individual’s specific vaccination needs can also increase motivation.

Spotlight: Cultivating culturally supportive health care settings

Ontario Native Women’s Association (ONWA)

ONWA has created cultural training focused on Indigenous women to address racism and discrimination. The training aims to improve safety for Indigenous women accessing health services and is targeted towards non-Indigenous health care professionals. It is currently being piloted across Ontario.

In response to a 2012 study showing that Black Ontarians were least likely to get the flu vaccine,

Developed with input from the community, this approach recognizes the impact of both past and present anti-Black racism in health care. It addresses vaccine concerns through culturally relevant resources that reflect the values and beliefs of the Black community.

Creating a centralized Provincial Immunization Resource Centre with up-to-date information for both health care providers and the public is an important step to build vaccine confidence in Ontario. This centre would make it easier for people to find reliable vaccine information, reduce the burden on health care providers and families, and help fight misinformation—a major cause of vaccine hesitancy.

Empowering vaccine ambassadors to build vaccine confidence in their communities

Local vaccine ambassadors are important ‘trusted messengers’ for public health messaging, especially in marginalized and hard-to-reach communities.

Figure 33. Vaccine Engagement Teams (VETs)

- 1Increased vaccine confidence, access and equity

Community Ambassadors reached residents experiencing hesitancy and access issues and increased vaccine confidence, access and uptake.

- 93% of surveyed residents reported that Ambassadors helped increase their confidence in the vaccine

- 87% of surveyed Ambassadors reported that VET strategies helped to improve vaccine access

- 82% of surveyed agencies reported that their teams responded to the needs of equity deserving groups

- 2Effective ambassador outreach and engagement

VETs implemented diverse and creative engagement strategies that addressed community needs.

- 76% of Ambassadors reported that culturally relevant information helped increase vaccine confidence

- 88% of Ambassadors reported building a stronger connection with their neighborhood through this role

- Engagement in multiple languages and access to vaccine data (e.g., case counts) were central to the program’s success.

Source: City of Toronto. Vaccine engagement teams: Program evaluation info sheet. 2022.

Community health workers and community ambassadors can play a complementary role to health care providers by providing opportunities for nuanced and time-intensive conversations about immunization that many individuals and families want and need, and that health care providers may not always be able to provide in clinical settings.

A provincial immunization information system would have the capacity to link vaccine coverage data to sociodemographic information, enabling monitoring of the effectiveness of vaccine confidence interventions. Ongoing monitoring will help evaluate the success of targeted approaches to improving confidence, which could include the implementation of a community health worker model.

Spotlight: ONWA’s Mindimooyenh Vaccine Clinic

Ontario Native Women’s Association’s (ONWA)’s Mindimooyenh vaccine clinic incorporates culture by offering traditional medicine, smudging and other Indigenous supports. They use a “family unit” approach, allowing families to attend together, combining traditional and western healing.

ONWA addresses vaccine hesitancy with culturally relevant videos where community members share their vaccination experiences. The videos are shared on ONWA’s website, social media and with other Indigenous partner agencies to reduce anxiety around immunization.

Mitigating pain and needle anxiety

Most children and 24% of adults fear needles.

The CARD™ system reduces stress reactions (pain, fear, fainting) using simple strategies. In a trial, students using CARD reported less fear and dizziness and had more positive attitudes about vaccination.

- Comfort

- Short Sleeves

- Snack

- Ask

- Numbing cream?

- Look at needle?

- Relax

- Frend

- Privacy

- Distract

- Talk to someone

- Play with phone

Source: Taddio A, Bucci LM, Logeman C, Gudzak V. The CARD system: A patient-centred care tool to ease pain and fear during school.

Optimizing public health messaging

Maximizing the impact of public health messaging related to immunization is a delicate balance; too much information can cause disengagement