Golden Eagle Recovery Strategy

This document is the recovery strategy for a species at risk – the Golden Eagle.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There was a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy.

The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Wyshynski, S.A. and T.L. Pulfer. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 43 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2015

ISBN 978-1-4606-3081-5 (PDF)

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Michelle Collins au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Authors

Sarah Wyshynski (ecological consultant)

Tanya Pulfer (ecological consultant)

Acknowledgments

This recovery strategy was greatly improved by guidance from the core advisory group for Golden Eagle, including:

- Laurie Goodrich (Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Kempton, PA);

- Todd Katzner (West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV);

- Charles Maisonneuve (Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune, Québec);

- Tricia Miller (West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV);

- Donald Sutherland (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Natural Heritage Information Centre);

- Junior A. Tremblay (Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune, Québec); and

- Maria Wheeler (Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA).

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Golden Eagle was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Executive summary

The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) is found predominantly in western North America, but historically was more widespread in the eastern United States and Canada. The Golden Eagle population in eastern North America is currently estimated at only a few hundred pairs. This population historically bred in eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. Currently, breeding of the eastern North American population is limited to Manitoba, remote northern areas in Quebec and Ontario, the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec and Labrador. The Golden Eagle is listed as endangered on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List.

Breeding history of the species in Ontario has not been well documented. Recent aerial surveys of known and potential nesting sites by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF), and surveys associated with the two Ontario Breeding Bird Atlases (1981-1985 and 2001-2005) have substantially increased knowledge of the species’ breeding distribution in Ontario. All documented nests from these surveys have been found in the Hudson Bay Lowlands region and the Severn River drainage of the Kenora District. It is estimated that approximately 10 to 20 pairs nest in Ontario; however, due to the difficulty in surveying the potential breeding range of the species, the fact that nest sites can be missed during aerial surveys and the belief that the total population may be/likely is augmented by an unknown number of non- breeding “floaters,” a confident assessment of the total number of breeding pairs in Ontario is not currently feasible.

Golden Eagles in eastern North America are faced with many direct and indirect threats, such as: lead poisoning, incidental trapping, shooting, electrocution and collisions with structures that obstruct flight paths, disturbance at nest sites, habitat loss, environmental contamination and climate change. The extent of many of these threats to the Ontario Golden Eagle population currently remains unknown and needs further investigation. There is some evidence that the Golden Eagle may never have been common in Ontario. The apparently small breeding population in Ontario may be its greatest limiting factor. A loss of a few individuals as a result of any of the identified threats may have demographic consequences to an already small population.

The goal for the species, identified in this recovery strategy is to maintain existing individuals and populations, allow for the natural increase of successfully breeding Golden Eagles in Ontario and minimize threats. The protection and recovery objectives are to:

- identify, reduce and mitigate threats to Golden Eagle and its breeding and non- breeding habitat in Ontario;

- identify and protect currently occupied and newly identified habitat of Golden Eagle in Ontario;

- increase knowledge of Golden Eagle biology in Ontario including distribution, abundance, life history, habitat needs and impact of threats to this population; and

- increase public awareness and understanding of Golden Eagle and its habitat in Ontario.

It is recommended that historical, current and newly discovered nesting sites (occupied and unoccupied) be considered for inclusion within a habitat regulation. Golden Eagles are known to reuse nest sites and refurbished several nests in one year. The time between nest reuse is variable, and has been observed to range between one and 30 to 40 years. At present, survey efforts for nests in Ontario are rare and infrequent, making data on Golden Eagle nest use limited. It is therefore suggested that nest sites that have been identified as either occupied or unoccupied within the last 35 years be considered for inclusion within a habitat regulation.

Given the importance and sensitivity of cliff habitat for nesting, it is recommended that habitat for cliff nests should include the cliff face on which the nest rests, and extend vertically from the top of the cliff to the base and horizontally across the entire cliff face. At sites where Golden Eagles nest in trees, it is recommended that regulated habitat should include the nest, the tree supporting the nest, and an area with a 22 m diameter around the nest tree to protect the tree itself.

The use of habitats by Golden Eagles in Ontario outside of their breeding season is currently not well documented. It is recommended that provisions should be made to incorporate any future information gathered on migration corridors and stop-over sites (habitat used for resting, roosting and foraging during migration) for inclusion within a habitat regulation.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

- Common name: Golden Eagle

- Scientific name: Aquila chrysaetos

- SARO List Classification: Endangered

- SARO List History: Endangered (2004)

- COSEWIC Assessment History: Not at Risk (1996)

- SARA Status: No Schedule, No status

- Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5

NRANK: N4N5

SRANK: S2B

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos); Giniw in Ojibway or Mikisiw in Cree) is one of two eagle species in North America and one of the largest birds in North America. It has long, broad wings, with a wingspan ranging from 185 to 220 cm and body length ranging from 70 to 84 cm. Sexes are similar in appearance although females (3.9 – 6.1 kg) are generally larger than males (3.0 – 4.5 kg) (Clark and Wheeler 1987).

The Golden Eagle has three recognizably distinct plumages: adult, sub-adult and juvenile (Wheeler and Clark 1999). In all plumages, head, body and coverts are dark brown, except for a golden crown and nape and rufous under tail coverts. Juvenile plumage (0 – 1 year) is much darker than adult as a result of all feathers being fresh or unworn. Flight feathers are uniform grey, although undersides of flight feathers typically have white bases, forming distinct patches or “windows” on underwings. The amount of white on the undersides of the primaries can be variable and some juveniles do not show any white (Brown and Amadon 1968, Wheeler and Clark 1999). The tails of immature eagles have a white base and dark brown tip with a sharp, well defined boundary between them (Wheeler and Clark 1999). Golden Eagles lose their juvenile appearance and gradually acquire their adult plumage over four to five years. Sub- adults (1 – 4 years) have varying amounts of white in the tail and in the flight feathers, which are progressively replaced by darker feathers as birds near adulthood. Adult plumage often looks mottled as it is composed of a combination of fresh dark feathers and faded older feathers. The subtle transition that takes place from juvenile to adult makes it sometimes impossible to determine age class in the field, even with experience and excellent views (Clark and Wheeler 1987, Kochert et al. 2002).

Confusion is possible between Golden Eagles and immature Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) which can also appear mostly dark brown. Features that most easily distinguish Golden Eagles from immature Bald Eagles and other North American raptors are the golden nape, legs feathered to the toes, head projecting less than the tail length, and a tri-coloured bill and cere. In addition, Golden Eagles often soar with wings held in a slight dihedral. Other distinguishing features of immature Bald Eagles are the white axillaries and underwing coverts, the dark edges on the white undertails, and the noticeably larger head and bill than Golden Eagle (Clark and Wheeler 1987).

Species biology

Golden Eagles reach maturity around five years of age and are believed to live approximately 20 to 30 years in the wild (Kochert and Steenhoff 2012, Lutmerding and Love 2013). They typically form monogamous pair bonds that can last several years (Watson 2010). Non-migratory populations (residents) have been found to maintain pair bonds year-round (Harmata 1982, Bergo 1987); however, little information is known about year-round pair bonds in migrants.

Throughout much of the Golden Eagle range, pairs lay eggs in March and April, although egg laying can commence as early as February in the southern edge of its North American range and as late as mid-June in the Arctic (Kochert et al. 2002). In Ontario, it is believed that the commencement of egg laying takes place in late April to early May, based on the estimated age of nestlings observed in nests in Ontario and adjacent Quebec (Sutherland 2007, Morneau et al. 2012). Details on when pairs arrive at nest sites, begin refurbishing nests and initiate egg laying, has yet to be documented in Ontario (Sutherland 2007). Golden Eagles lay one to four eggs with most clutches containing two eggs. Incubation, mostly by the female, begins as soon as the first egg is laid with incubation ranging from 41 to 45 days (Abbott 1924, Beecham and Kochert 1975). Young leave the nest at 65 to 75 days but occasionally will remain in the nest for more than 80 days (DeSmet 1987). Once fledged, the young will remain in the area around the nest for approximately two weeks, eventually following their parents away from the nest site (Collopy 1984).

Golden Eagles prey mainly on small to medium-sized mammals including rodents, hares and rabbits but will also prey on birds (Kochert et al. 2002). While Golden Eagles are capable of taking larger bird and mammal prey such as cranes, swans, deer and domestic livestock, they rarely attack large prey (Kochert et al. 2002). Golden Eagles in eastern Canada are believed to feed more frequently on birds (waterfowl and wading birds) than Golden Eagles in western North America (Katzner et al. 2012a). When live prey is scarce, in particular between October and March, eastern Golden Eagles often feed on carrion such as Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), Moose (Alces alces) and White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (Katzner et al. 2012a).

Breeding success of Golden Eagles is highly variable throughout North America. Annual reproductive success of Golden Eagles is known to vary with prey abundance. In Idaho, the percentage of females that lay eggs each year is related positively to jackrabbit abundance (Steenhof et al. 1997). Prey abundance has also been known to influence annual reproductive rates in Utah, Alaska and Quebec (Smith and Murphy 1979, Bates and Moretti 1994, McIntyre and Adams 1999).

Golden Eagles in a number of northern areas have smaller broods and produce fewer fledglings (0.49 – 0.64 fledgling/pair) than those found in more temperate areas (Poole and Bromley 1988, McIntyre and Adams 1999, Morneau et al. 2012, Moss et al. 2012). It has been hypothesized that the lower productivity may be a result of the combination of high energetic costs associated with migration and low prey diversity on the breeding grounds (McIntyre and Adams 1999). Many breeding populations of Golden Eagles depend on cyclic prey and have few alternate prey sources when they first arrive at their northern breeding areas as prey abundance and diversity are at their lowest annual level (McIntyre 2002). While the relationship between latitude and productivity may be true in boreal Golden Eagles, it does not however seem to be applicable to Golden Eagles in Northern Quebec where a high density of Golden Eagle nests has been found (in the Kuujjuaq area) with a productivity higher than in the Gaspé Peninsula (J.A. Tremblay, pers. comm. 2013).

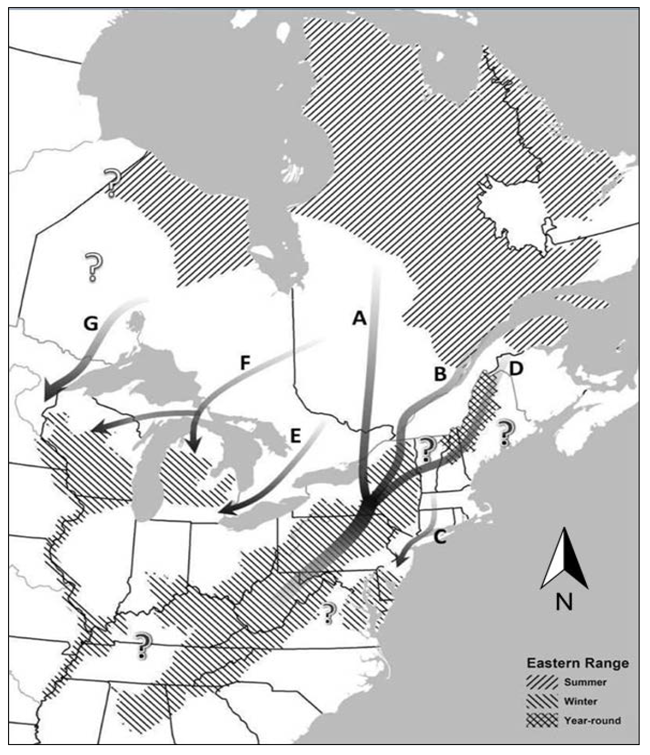

Not all populations of Golden Eagle are migratory; however, those occurring in eastern North America are migratory (Brodeur et al. 1996, Watson 2010). Eastern populations of Golden Eagles overwinter predominantly in the Appalachian mountain region and the Upper Midwest (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan and Iowa) (Katzner et al. 2012a). These birds migrate to Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Labrador to breed (Katzner et al. 2012a, Asselin et al. 2013). The majority of Golden Eagles breeding in Quebec and Labrador are believed to migrate west of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and cross the St. Lawrence River somewhere between Montreal and Quebec City, into the Appalachian Mountains of New York (Katzner et al. 2012a). Migratory routes of individuals summering in Ontario are unknown (Katzner et al. 2012a). Golden Eagles have been known to follow topographical features in migration such as the Appalachian Mountains, although Ontario, having very little topography, does not have substantial features that are likely to influence migration (Brodeur et al. 1996). Like most migrating raptors, Golden Eagles avoid crossing large bodies of water, such as the Great Lakes, where thermal or wind-generated lift is minimal or non-existent, thus diverting migration routes around such barriers (Brodeur et al. 1996).

Fall migration in eastern North America begins as early as mid-August, although the majority of migration takes place from mid-October through mid-December (Katzner et al. 2012a). Spring migration typically occurs between late February and mid-May although the majority of the movement occurs in mid-March (Katzner et al. 2012a). In a recent telemetry study investigating migration of Golden Eagles in eastern North America, Miller et al. (2011, unpub. data) found a distinct difference between arrival at the southern (48 – 51 degrees latitude) nesting areas and northern (> 52 degrees latitude) nesting areas of Quebec and Labrador. Arrival of adults at the southernmost breeding sites occurred as early as February 21 and as late as March 24 with an estimated peak arrival date from March 9 to 14. Arrival of northern nesting adult birds was from March 29 to April 27 peaking in the first two weeks of April. Additionally, they found two distinct waves of departure dates from wintering grounds (West Virginia, New York, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Alabama, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Maryland), regardless of breeding latitude, with the first wave peaking in the first two weeks of March and the second in mid-April (Miller et al. 2011, unpub. data). The first group consisted mainly of adults and some older sub-adults. Juveniles and younger sub- adults made up the second group with estimated peak arrival dates for young birds being about one month later than adults. Similarly during the fall, adults and older sub- adults were found to move later than younger birds although the same bimodal distribution has not yet been documented. Additionally, Miller et al. (2011) noted birds arriving on the wintering grounds as late as mid-January and leaving as early as mid- February. Of 60 birds tracked in the study, two adult birds migrated into Ontario - one from Alabama and one from Pennsylvania. Both showed similar timing as those birds migrating to Quebec (T. Miller, pers. comm. 2013).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

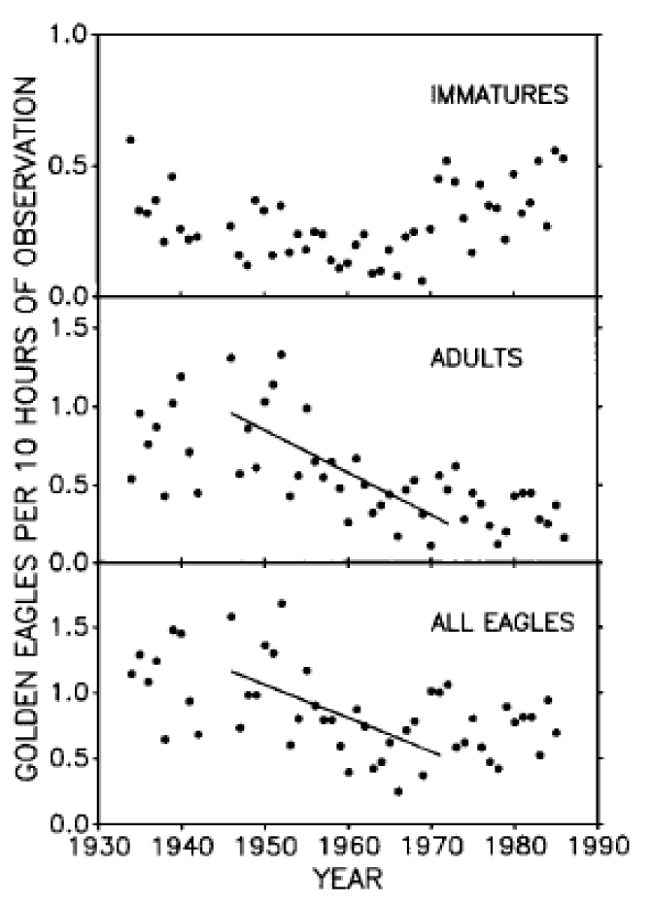

The Golden Eagle is the most widely distributed of the world’s large eagle species, inhabiting a broad range of latitudes throughout the Northern Hemisphere (De Smet 1987, Kochert et al. 2002). In North America, the Golden Eagle is found predominantly in the west but historically was more widespread in the eastern United States and Canada (Kochert et al. 2002). Over the past century, the eastern population has undergone long term declines (see Figure 1, Bednarz et al. 1990). Data from Ontario (Hussell and Brown 1992) and five migration sites in the eastern United States (Titus and Fuller 1990), however suggest a stable or increasing trend since the banning of dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) in 1972 (Kochert and Steenhof 2002, Katzner et al. 2012a). Recent short term trends (1994 – 2004) based on counts at migration watch sites in the central Appalachians are largely positive, with significant annual increases of two to four percent (Farmer et al. 2008). Kirk (1996) estimated the Golden Eagle population in eastern North America at only a few hundred pairs. These data may not represent the current population but may be the best “current estimate” of the population. If populations have increased since DDT and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were banned, the population could have grown substantially.

Knowledge of the breeding distribution of eastern Golden Eagles is limited. Prior to 1994, fewer than 20 Golden Eagle territories east of Manitoba were recorded in Canada (Kirk 1996, Morneau et al. 1994). Golden Eagles historically bred in eastern Canada and the northeastern United States (Katzner et al. 2012a). Currently, breeding is limited to Manitoba, remote northern areas in Quebec and Ontario, the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec and Labrador. With more intensive survey efforts since 1994, the greatest number of breeding pairs is believed to be above 50°N in northern Quebec (Katzner et al. 2012a) where there are estimates of 300 to 500 pairs (Brodeur and Morneau 1999).

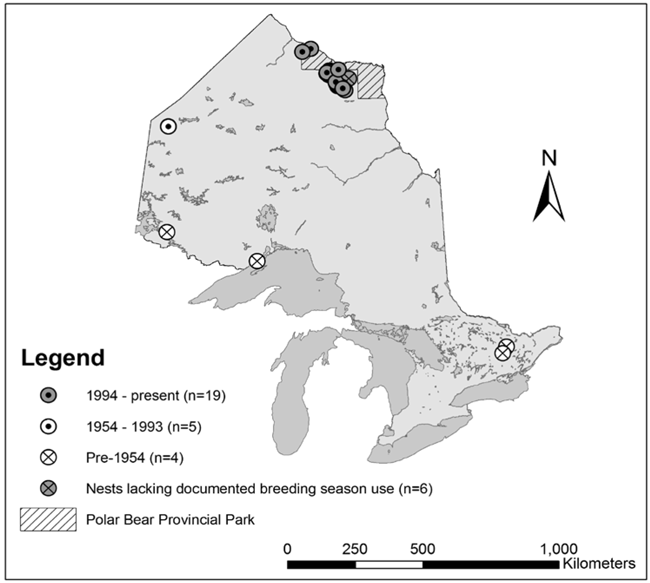

Breeding history of the species in Ontario has not been well documented. Several unsubstantiated nesting reports date back to the late 1800s (De Smet 1987) with the first documented Golden Eagle nest in the province in 1959 (Peck and James 1983). Recent aerial surveys of known and potential nesting sites by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (Sutherland 2007; NHIC 2013) and surveys associated with the two Ontario Breeding Bird Atlases (1981-1985 and 2001-2005; Cadman et al. 1987, 2007) have substantially increased knowledge of the species’ breeding distribution in Ontario. All documented nests from these surveys have been found in the Hudson Bay Lowlands region and the Severn River drainage of the Kenora District (Sutherland 2007) (Figure 2). Most of these nests have been found in the Sutton Ridges which is one of the few areas of significant topographical relief in the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Although there are currently only a few dozen known nest sites in Ontario, observations of individuals in suitable breeding habitat during the breeding season (Cadman et al. 2007, NHIC 2013) suggest that more nests may be in the province. Recent surveys and Breeding Bird Atlas data estimate approximately 10 to 20 pairs nesting in the Hudson Bay Lowlands and the Northern Shield regions of Ontario (Sutherland 2007). However a confident assessment of the total number of breeding pairs in Ontario currently is not feasible due to a number of factors, including: (1) the difficulty in surveying the potential breeding range of the species; (2) the fact that nest sites can be missed during aerial surveys and (3) the belief that the total population may be augmented by an unknown number of non-breeding “floaters” (D.A. Sutherland, pers. comm. 2013).

Most populations of Golden Eagles include non-territorial adults known as floaters. Floaters are individuals that do not nest because all suitable territories are occupied. They are believed to fill vacancies as they occur, contributing to population stability (Newton 1979, Hunt et al. 1999). Distribution and abundance of floaters, along with their influence on population dynamics in Ontario is unknown.

It has been suggested through hawk migration count data, that 15 to 25 percent of eastern Canada’s Golden Eagles migrate through the Great Lakes region of Ontario (Katzner et al. 2012a). Migration routes through Ontario are poorly known, although telemetry data of migrants has shown movement along the western edge of Lake Superior and the southern shores of Lake Ontario, continuing west of Lake Erie (Figure 3) (Brodeur et al. 1996, Mehus and Martell 2010). To what extent Golden Eagles use, and require these areas for foraging and roosting during their migration to and from their breeding ranges remains unknown.

1.4 Habitat needs

Golden Eagles can be found throughout much of the northern hemisphere. They use a wide variety of habitats throughout their range, inhabiting open and semi-open country such as prairies, sagebrush, arctic and alpine tundra, savannah or spruce woodlands and barren areas. In particular they are found in hilly or mountainous terrain, along rivers and streams in areas with a sufficient prey base and near suitable nesting sites (Watson 2010, NatureServe 2012). The breeding habitat of Golden Eagles in eastern North America is typically found at the boundary of tundra, boreal forest and wet meadows (Katzner et al. 2012a). This species usually forages in open habitat, preferring areas with short or sparse vegetation especially slopes and plateaus that permit a broad view and use of air currents for soaring (Beebe 1974, Olendorff et al. 1981). In general Golden Eagles tend to avoid heavily forested areas as they do not provide good foraging habitat. However, birds in the Gaspé Peninsula and the former breeding range in the United States have been known to nest in forested habitats, foraging in nearby open landscapes created by disturbances and wetlands (Katzner et al. 2012a).

Structures on which Golden Eagles build their nests can vary throughout their range and with availability of nesting sites. Golden Eagles usually nest on cliffs, but are also known to select nest sites in the upper third of deciduous and coniferous trees, as documented in Manitoba (Asselin et al. 2013), Montana (McGahan 1968) and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec (Brodeur and Morneau 1999). Occasionally nests will be built on artificial structures such as traditional wind mills, electrical transmission towers and nest platforms (Kochert et al. 2002), although none have been documented in eastern North America. Golden Eagles avoid nesting near urban habitat (Pagel et al. 2010). In Ontario most nests have been found on remote, difficult to access bedrock cliffs overlooking large burns, lakes or tundra (Sutherland 2007, Armstrong et al. 2013). Nests in Ontario have also been documented on cliffs saddling spruce trunks and occasionally they have been found in tall white spruce along riparian corridors (Sutherland 2007, NHIC 2013), as similarly documented in northern Manitoba (Asselin et al. 2013).

Both sexes participate in nest building prior to incubation in addition to adding fresh vegetation to the nest throughout the nesting season (Kochert et al. 2002). Eagles weave sticks into the existing nest structure creating a platform for nesting, which is then lined with a variety of vegetation types including dead and green leaves, grasses, soft mosses and lichens (Palmer 1988, Kochert et al. 2002, Watson 2010). Many nests have an unobstructed view of the surrounding habitat (Beecham and Kochert 1975), and may be located on slopes that provide wind lift for flight. Proximity to hunting grounds is considered an important factor in nest site selection, as is weather condition at the beginning of the nesting season (Morneau et al. 1994). Certain exposures may protect nests from inclement weather (Watson and Dennis 1992, Morneau et al. 1994). In northern areas nests are typically found on south-facing slopes, reducing exposure to cold and avoiding prevailing winds (Morneau et al. 1994). However, in regions where suitable nest sites are limited, Golden Eagles show no directional preference (Mosher and White 1976). South-facing slopes may be the only available nesting habitat free of snow when birds first arrive in the spring (Amaral and Gardner 1986). Nests in northern regions often have overhangs which are thought to protect nests from precipitation (rain and snow) and ice formation, along with shading from the sun. Although falling rocks or soil can kill incubating eagles or nestlings (Kochert et al. 2002).

Golden Eagles typically refurbish and reuse existing eagle nests. Freshly built nests may or may not be used the year of construction and several nests may be refurbished in one year, until eggs are laid in the selected nest (Pagel et al. 2010). The number of alternate nests/territory is usually between two and three, although territories with up to 14 nests have been identified (Kochert et al. 2002). Distance between alternate nests can be less than one metre and greater than five km (McGahan 1968, Morneau et al. 2012). The number of alternate nests, and distance between them, is thought to be related to proximity to other nesting pairs along with terrain features (Boeker and Ray 1971). Maintaining multiple nests may be important for courtship and pair bonding (Kochert and Steenhof 2012). Alternate nests may also be important to Golden Eagles in the event that a nest becomes damaged close to the time of laying and the pair may need to relocate (Newton 1979, Watson 2010). Additionally, pairs may change nests after a failed reproductive effort, disturbance or turnover of adults (Kochert and Steenhof 2012). The pair may use the same or alternate nests in consecutive years. Unused nests may be reused after decades of nonuse. Kochert and Steenhof (2012) found some nests reused or new nests built on top of former nests after 30 to 40 years of nonuse.

Average home range size of Golden Eagles varies in relation to prey distribution and abundance, type of habitat occupied and the availability of conditions favourable to soaring and hunting (De Smet 1987). In the western United States, the average home range size during the breeding season is 20 to 33 km² (Kochert et al. 2002). In the Hudson Bay region of northern Quebec, home range size varied from 845 to 1,585 km² (Brodeur 1994). In the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec, home range size varied from 515 to 2,132 km² (Katzner et al. 2012a). Males and females typically have similar home range size during the breeding season (Dunstan et al. 1978), which tends to increase with total number of young fledged (Marzluff et al. 1997).

Home range size has been found to vary with availability of open habitat and therefore availability of hunting grounds. In Quebec it was found that birds with high availability of open habitats had smaller home ranges than birds with low availability of nearby open habitats (J.A. Tremblay, unpub. report). Information regarding home range size in Ontario is lacking, yet given geographic proximity, territory usage may be similar to Golden Eagles breeding in the Hudson Bay region of northern Quebec. Investigating the similarities between breeding territories in northern Quebec and Ontario would however be beneficial before making assumptions, as territory usage seems to vary significantly between different regions of North America.

During the winter most eastern Golden Eagles are observed within or along the southwestern border of the Appalachian Plateau and within the Coastal Plain physiographic region (Kochert et al. 2002). It has been thought that these birds are found predominantly in managed wetlands and reservoirs such as wildlife refuges, where habitat is open, human disturbance is limited and the prey population is abundant (De Smet 1987). However, Miller (2012) found that most birds are found – but rarely seen – in the forests across the Appalachians. They were found to primarily use deciduous forest, not open areas as previously suggested. A negative correlation between percentage of forest cover and home range size was found to exist in eastern wintering Golden Eagle populations (Miller 2012).

1.5 Limiting factors

Limiting factors are intrinsic attributes that may constrain a species’ recovery potential. For Golden Eagles in Ontario one of the main factors limiting the population is its apparently small breeding population. Small populations comprising few, isolated breeding units are intrinsically vulnerable to stochastic events (Begon et al. 1996). Low population densities may make it difficult for eagles to find mates thus resulting in decreased breeding success.

Reproductive success of Golden Eagles is tied to the abundance of its principle prey in the early stages of the nesting season (McIntyre 2002). Low prey density on northern breeding grounds combined with the energetic costs associated with migration is believed to account for the observed lower productivity of Golden Eagles in several northern regions (McIntyre and Adams 1999). Common prey such as Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) experience large amplitude population cycles (McIntyre and Adams 1999). Productivity of Golden Eagles may be affected in years when prey availability is low. However, Golden Eagles in Ontario are believed to prey heavily on water birds and carrion therefore eagles in Ontario may be resilient to fluctuating population cycles of mammalian prey. Further research on prey availability in Ontario and prey preferences by eagles in Ontario would provide a better understanding of whether or not prey is a limiting factor for Golden Eagles in Ontario.

Availability of nest sites may also be a limiting factor as much of the current breeding area in northern Ontario has little topography thus offering limited cliff nesting sites. The lack of cliff nesting sites may, however, suggest that tree nesting sites may be important to this population. Further survey efforts are needed to understand to what extent Golden Eagles in Ontario use trees for nesting.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Threats to Golden Eagles in Ontario were identified based on modified International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN 2010

Threats for the breeding population of Golden Eagles in Ontario have been identified both within Ontario (identified as “Ontario”) and throughout their geographic range in eastern North America (identified as “Range”). Notably the extent of each of these threats within Ontario is largely unknown (see section 1.7 Knowledge Gaps).

Lead poisoning (Ontario: unknown threat; Range: high threat)

Lead poisoning from ingestion of lead shot or bullets in hunter-killed game birds and mammals is of great concern for Golden Eagle populations throughout North America (Kramer and Redig 1997). Eagles from nesting populations are likely exposed to lead contamination particularly during the winter when carcasses may be a large source of their food supply (Neuman 2009). Twenty-one Golden Eagles in eastern North America were recently sampled for elevated levels of lead. Results showed blood levels in 10 percent of the birds with very high levels (> 20 ug/dl), 35 percent with moderate levels (10-20 ug/dl) and 55 percent with low levels (< 10 ug/dl) of lead. It has been suspected that the birds with high levels of lead died – of which one was tracked to Ontario (Miller et al. unpub. data). Golden Eagles admitted to rehabilitation facilities in eastern North America have been found with clinical blood levels of > 0.25 ppm (Katzner et al. 2012a). In Montana, elevated levels of lead (> 0.20 ppm) were found in 56 percent of 86 eagles sampled between 1985 and 1993 (Harmata and Restani 1995). Lead poisoning in eagles may be lethal or sub-lethal. Mortality from ingesting lead occurs occasionally. In the prairie provinces of Canada, 31 Golden Eagles were necropsied during the early 1990s. Four out of 30 (13%) had been poisoned from lead and three (10%) of the 30 were sub-lethally exposed to lead (Wayland and Bollinger 1999). Between 1977 and 1986, seven (44%) of 16 Golden Eagles necropsied in Idaho were lead poisoned (Craig et al. 1990). Sub-lethal exposure may weaken eagles, predisposing them to reproductive failure, starvation, disease, predation or injury (Kramer and Redig 1997, Craig and Craig 1998).

Lead shot for hunting most migratory game birds was banned in the United States in 1991 and in Canada in 1999, although it can still be used for hunting upland game birds. Bullets used to hunt large game animals, such as moose and deer contain lead.

Studies have found that the incidence of lead ingestion in both Bald Eagles and Golden Eagles did not change after the ban of lead shot for waterfowl hunting (Kramer and Redig 1997). It has been suggested that big game hunting may be a more significant source of dietary lead exposure for eagles than lead ingested through bird hunting (Bedrosian et al. 2012). Rifle bullets and fragments can contaminate large portions of the meat. Eagles get lead poisoning when they feed on carrion or gut piles, which are believed to be a large part of their diet from October through to March (Katzner et al. 2012a). Hunting of game birds and large mammals is a socially and economically important activity for many people in Ontario. The level of exposure to lead along with the demographic impact it may pose on Golden Eagles in Ontario is unknown.

Trapping (Ontario: unknown threat; Range: high threat) and Shooting (Ontario: unknown threat; Range: medium threat)

Incidental trapping of Golden Eagles in leg hold traps and snares set for furbearing mammals has been documented in North America for more than a century (Katzner et al. 2012a). Between 2007 and 2010, multiple incidental captures were reported in Quebec, West Virginia and Virginia (Katzner et al. 2012a). In a telemetry study on Golden Eagles in eastern North America two of the five confirmed mortalities of telemetered eagles were killed in traps (Miller, pers. comm. 2013). Trapping of furbearing animals in Ontario dates back hundreds of years and continues to be a socially and economically important activity for many people as well a traditional practice for First Nation communities (OMNR 2011a). The number of incidental captures of Golden Eagles in Ontario is unknown; however, in neighboring Quebec there are reports of two to seven incidental captures per year (Brodeur and Morneau 1999). Recent estimates show that it can reach 20 Golden Eagles per year (J.A. Tremblay, pers. comm. 2013). It has been suggested that the actual number of birds trapped may be twice as many as reported (Katzner et al. 2012a). Trapping losses may have considerable impact on local populations that are already small.

Eagles have been known to be shot throughout their range, most frequently where depredation of livestock was suspected. Between 1960 and 1995 in the United States, at least 15 percent of known Golden Eagle deaths were a result of illegal shooting (Franson et al. 1995). The livestock industry is relatively small in Ontario, compared with many of the western states and provinces thus shooting of Golden Eagles in Ontario in defense of livestock may be rare occurring only in isolated instances. The extent of this threat in Ontario is unknown.

Disturbance at nest sites (Ontario and Range: medium threat)

Golden Eagle is one of several cliff and tree nesting species that is sensitive to human disturbance. Studies in the western United States have found that 85 percent of all Golden Eagle nest losses were a result of human disturbances (Boeker and Ray 1971). Disturbance can come from a variety of recreational activities, such as rock climbing, hiking, boating and use of all-terrain vehicles and snowmobiles. Breeding adults may be flushed from a nest by recreationalists and researchers, leaving the nest for extended periods of time, resulting in increased exposure to the elements (heat, cold, wind, rain), missed feedings and increased chick mortality (De Smet 1987). Disturbance can also result in eggs being knocked from the nest by startled adults or juveniles fledging prematurely (De Smet 1987). Noise associated with the development of oil, gas or coal mining facilities has also been known to lead to abandonment of nearby Golden Eagle nesting territories (Call 1979, Phillips et al. 1984). The effects of disturbance can range from loss of a year’s reproduction to permanent nest site abandonment (Pagel et al. 2010). The periods most critical for reproductive success of Golden Eagles are when the eagles are establishing territories and just prior to egg laying (Fyfe and Olendorff 1976).

Most outdoor recreational activities (e.g., fishing) in the areas around Golden Eagle breeding territories in Ontario do not begin until June when the lakes are free of ice and the period defined by Fyfe and Olendorff (1976) as most critical for reproductive success has passed. However, nest sites are still vulnerable to disturbance through June and July as fledging most likely does not occur until the end of July. If individuals climb or camp around the cliffs they could potentially disturb nesting eagles and threaten reproductive success. Additionally, hunting in northern Ontario is a way of life and most hunting and trapping in the winter is done by snowmobile. Disturbance by snowmobiles close to nesting territories during March and April when the birds are believed to be establishing territories and laying eggs, may possibly disrupt nesting birds and deter them from nesting in the area. Further research into the types and intensity of recreation occurring in proximity to Ontario Golden Eagle nesting territories is needed to assess whether or not they pose a threat to breeding birds.

Habitat loss (Ontario: low threat; Range: medium threat)

The loss of habitat is a serious threat to Golden Eagles in much of its world-wide range (De Smet 1987, Kochert et al. 2002, Katzner et al. 2012a). This species is limited by availability of nest sites and open habitat for hunting (Kochert et al. 2002). Fire suppression and afforestation are causing forest expansion in some regions and are believed to have negative effects on Golden Eagle productivity and territory occupancy (Marquiss et al. 1985, Watson and Dennis 1992, Pedrini and Sergio 2001). In the area in which Golden Eagle nests in Ontario there is no fire suppression except in cases where wild fire is threatening communities. Wild fire in Ontario is likely an important factor in maintaining suitable open areas for foraging (Sutherland pers. comm. 2013). Forestry is a major industry in Ontario, with approximately 36.4 million hectares of forest being managed (OMNR 2009). However, commercial timber harvest does not take place within the current known breeding range of the Golden Eagle in Ontario and therefore does not currently pose a threat to Golden Eagle nest sites. However, it should be noted that this finding is based on minimal surveys in low visibility areas.

Mining and various types of energy development are found throughout Ontario. Loss of cliff nesting habitat as a result of mining activity (e.g. site disturbance and loss of habitat through excavation), may have negative consequences on eagle populations. Suitable cliffs for Golden Eagle nests are limited in Ontario’s northern breeding grounds as the region is mostly flat with few areas of significant topographic relief. The Sutton Ridges, where most of the recently confirmed nests occur, are a chain of igneous rock outcrops. Mineral exploration in this unique area is possible due to the nature of the bedrock. Mining activity would threaten the limited nesting sites in this area and alter habitat for Golden Eagle prey.

Collisions (Ontario: low threat; Range: medium threat) and Electrocutions (Ontario: low threat; Range: medium threat)

In the western United States one of the leading known causes of Golden Eagle mortality is electrocution and collisions with structures that obstruct flight paths such as towers, power lines and buildings (Franson et al. 1995). Eagles are particularly vulnerable to electrocution when landing on power poles and utility lines. Most mortality occurs where natural perches are lacking (Franson et al. 1995). In major problem areas steps have been taken to reduce electrocutions by designing poles with adequate separation of energized hardware, insulating wires and hardware and installation of perches above energized objects to encourage perching in safe locations (Olendorff et al. 1981). In the East however, very few cases of electrocution occur, in great part due to different landscapes (other roosting possibilities than in western areas where poles comprise the majority of available roosting structures) and also due to different electrical installations (C. Maisonneuve, pers. comm. 2013, J.A. Tremblay, pers. comm. 2013). Estimating mortality of Golden Eagles caused by electrocution in Ontario is difficult due to the remoteness and number (>150,000 km) of power lines throughout the province.

The impact of wind farms on Golden Eagle populations has been considerable in the western United States (Kingsley and Whittam 2001, Manville 2005). In California’s Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area, an average of 67 Golden Eagles are killed each year by turbine blade strikes (Smallwood and Thelander 2008). Studies investigating the impacts of wind facilities on Golden Eagles have found approximately 55 percent of mortalities is a result of striking a wind turbine, 18 percent from electrocution, 11 percent from collision with wires and 16 percent from undetermined causes (Orloff and Flannery 1992). Where raptor densities are low mortality from wind farms is generally lower. At present no Golden Eagles have been reported killed by wind turbines in eastern North America (Katzner et al. 2012a) although there have been reports of Bald Eagles killed. However, with an increasing number of large wind energy facilities being developed in eastern North America there is a growing concern of mortalities associated with these facilities in Golden Eagle breeding, wintering and migrating ranges.

Wind energy facilities are often created in large open areas, which are used by Golden Eagles and other raptors for hunting (Hunt et al. 1999). Additionally, wind energy facilities have been known to open up large areas of land, creating hunting areas for Golden Eagles and other raptors. Eagles nesting in areas with low availability of nearby open habitat are thought to be attracted to these openings created near wind facilities because of increased hunting opportunities. However, hunting in these areas increases the risk of collision with turbines (Hunt et al. 1999, Tremblay et al. 2010). The altitude at which eagles fly influences the relative risk they experience from turbines, which typically have a rotor-swept zone of 50 to 150 m above ground. Katzner et al. (2012b) found that Golden Eagles actively engaged in migration fly at higher elevations than locally moving birds. Locally moving birds are thought to be moving at low altitudes in order to facilitate foraging, roosting and perching; whereas, actively migrating birds are searching out and utilizing lift to minimize energy expenditure. Locally moving birds were also found to turn more frequently. The combination of low altitude flight and frequent direction changes exposes locally moving birds to a greater risk of collision with wind turbines than birds in active migration.

Golden Eagles flying over steep slopes and cliffs fly at a relatively lower altitude than birds flying over flat and gentle slopes. This is most likely due to the orographic lift that is generated around cliffs and steep slopes (Katzner et al. 2012b). Thermals develop during relatively calm conditions but break down with strong winds (Duer et al. 2012). During migration when thermals are unavailable, Golden Eagles tend to fly low along ridges and coastlines using the orographic lift and avoiding water crossings. At such places they are highly vulnerable to collisions, often flying within the turbine sweep zone and they tend to be highly concentrated in these corridors on windy days (Duer et al. 2012).

Wind energy facilities are currently not found in areas near Ontario Golden Eagle breeding territories, although this has potential to be a concern in the future. Eagles migrating along the shores of the Great Lakes, on their way to and from their breeding territories could potentially be affected by the growing number of wind energy facilities around the Great Lakes.

Environmental contamination (Ontario and range: low threat)

Because of their primarily mammalian diet, Golden Eagles are believed to be less susceptible to pesticide contamination than other raptors (Reichel et al. 1969, Reidinger and Crabtree 1974). However, unlike Golden Eagles in western North America, birds in the east are known to prey more heavily on predatory water birds high in the aquatic food chain (Spofford 1971, Singer 1974). It is therefore thought that polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorines, such as DDT may have contributed to the Golden Eagle population decline between 1946 and 1973 in the northeastern United States (Todd 1989, Bednarz et al.1990, Kirk 1996). While raptor populations have made significant gains since the banning of DDT and other chemical substances in North America, new and emerging chemicals may pose a potential problem to Golden Eagles in the east. In particular, mercury may be of concern for birds feeding on water birds (Bocharova et al. 2013). Additionally, there has been increasing concern about the effects of various contaminants (pharmaceuticals, etc.) fed to livestock on scavengers. When scavengers such as Golden Eagles, feed on carcasses that have recently died and have not been buried properly, some get sick and may even die (Maisonneuve, pers. comm. 2013).

Climate change (Ontario and range: unknown threat)

Climate change is believed to bring about erratic weather events which may affect Golden Eagle populations especially if such events occur during incubating of eggs and brooding of young. If unfavourable weather conditions which result in loss in productivity, such as unusually cold and wet weather or unusually hot and dry weather, persist over consecutive years, Ontario’s small population may be severely affected. Additionally, climate change may affect migration distance and wintering areas used by the birds as well as migration timing (Visser et al. 2009). Birds may linger on their northern breeding grounds during warmer autumns/early winters and may also arrive at their breeding grounds earlier in conjunction with warmer spring weather. The degree to which climate change will affect Golden Eagle productivity is unknown.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

The following gaps exist in our knowledge about Golden Eagles.

Life history

- Timing at which pairs arrive at nest sites, begin refurbishing nests and initiate egg laying in Ontario.

- Natal dispersal distances of birds breeding in Ontario.

- Nest site fidelity in Ontario.

- An understanding of the contribution of non-breeding adults to population viability.

Population demographics in Ontario

- Basic population demographics (age structure, fledging rate, natality and mortality) of Golden Eagles in Ontario.

- Nest productivity for Golden Eagles (number fledged/nest) in Ontario.

- Trend data on nest productivity over time.

- Age-specific survival rates for Golden Eagles in Ontario.

- Up-to-date information on location, population size and trends for breeding sites in Ontario.

- Thorough assessment of the number of Ontario breeding pairs and nest sites. Habitat (breeding, foraging and migration)

- Habitat factors that are critical to breeding and foraging in Ontario.

- Extent of trees used for nesting structure by Golden Eagles in Ontario.

- Foraging distances and home range size of nesting Golden Eagle pairs in Ontario.

- Availability and composition of Golden Eagle prey on breeding territories in Ontario.

- Identification of important/preferred prey of Golden Eagles in Ontario.

- Migration routes/corridors of Golden Eagles to and from breeding territories in Ontario.

- Migratory stopover sites in Ontario, which may act as critical feeding/refueling areas.

- Identification of and fidelity to wintering areas.

- Similarities between breeding territories of Golden Eagles in Quebec and Ontario.

Threats

- Occurrence and frequency of incidental/accidental deaths of Golden Eagles through trapping, electrocution and collision with structures in Ontario.

- Number of Golden Eagles shot annually in Ontario.

- An understanding of the tolerance levels for various forms of human disturbance adjacent to nest sites, and the required size of buffers around nests to minimize the impacts of human disturbance.

- Impacts of lead poisoning on Ontario Golden Eagles.

- Impacts of new and emerging chemical substances on Golden Eagles in Ontario.

- Impacts of pharmaceuticals from dead livestock not appropriately buried on Golden Eagles.

- Effects of wind turbines on Golden Eagle nesting and migration in Ontario.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

The following Golden Eagle recovery actions have been completed and/or are currently underway.

Management

- The use of DDT was prohibited in 1972 in Canada and the United States.

- The use of lead shot for hunting most migratory game birds was banned in the United States in 1991 and Canada in 1999.

- In 1987, Ontario developed Golden Eagle habitat management guidelines for forest management plans (OMNR 1987a) based on the guidelines for Bald Eagle (OMNR 1987b) with slight modifications.

- OMNR’s current forest management-related direction for nest sites of birds of prey is contained within the Forest Management Guide for Conserving Biodiversity at the Stand and Site Scales (OMNR 2010). This document does not contain direction for nests of the Golden Eagle because the species is not known to nest within that portion of the province subject to crown land-based forest management operations.

- Golden Eagle receives species and general habitat protection under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

Inventory

- Surveys have been conducted for breeding evidence of Golden Eagles with the last two Ontario Breeding Bird Atlases (1981-1985 and 2001-2005) (Cadman et al. 2007).

- Aerial surveys of known and potential Golden Eagle nest sites were conducted in the Sutton Ridges and the lower Shamattawa River in July of 1994 (Scholten and McRae 1994).

- A known Golden Eagle nest site on the Severn River in the Red Lake OMNRF District, was observed sporadically from 1968 through 1978 and again in July of 2008 by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (Armstrong et al. 2013).

- Aerial surveys have been conducted by the OMNRF (Sutherland 2007 unpub. data) throughout known Golden Eagle breeding habitat.

- Thirteen Hawk Watch sites located throughout Ontario, gather observations of raptors migrating on an hourly or daily basis. The data is recorded in a format that may later be retrieved, reported and analyzed.

- Golden Eagle observations throughout Ontario (and elsewhere) are being submitted to eBird, a database where vast numbers of bird observations are made each year by recreational and professional bird watchers. These observations provide bird abundance and distribution data at a variety of spatial and temporal scales.

- The Wind Energy Bird and Bat Monitoring Database (a joint initiative of the Canadian Wind Energy Association, Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Bird Studies Canada and OMNRF) provides data summaries of species composition and seasonal fatality patterns of birds and bats in relation to wind turbines, as well as expanded analysis and interpretation.

- Telemetry studies of migrating Golden Eagles have been conducted in Quebec (Brodeur et al. 1996) in addition to currently ongoing studies in Quebec and the eastern United States (initiated by C. Maisonneuve and T. Katzner), and the upper mid-western United States (initiated by a partnership between Audubon Minnesota, The National Eagle Center, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Nongame Program and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources). Some of the telemetered birds have been tracked migrating through Ontario.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal is to maintain existing individuals and populations, allow for the natural increase of successfully breeding Golden Eagles in Ontario and minimize threats.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

[Table 1 converted to a list]

- Identify, reduce and mitigate threats to Golden Eagle and its breeding and non-breeding habitat in Ontario.

- Identify and protect currently occupied and newly identified habitat of Golden Eagle in Ontario.

- Increase knowledge of Golden Eagle biology in Ontario including distribution, abundance, life history, habitat needs and impact of threats to this population.

- Increase public awareness and understanding of Golden Eagle and its habitat in Ontario.

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 2. Approaches to recovery of the Golden Eagle in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection management |

1.1 Avoid lead ammunition for hunting within the entire range of Golden Eagles breeding in Ontario

|

Threats

|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection management |

1.2 Work with fur trapping groups, such as the Ontario Fur Managers Federation, to develop best management practices to reduce incidental trapping in Ontario.

|

Threats

|

| Critical | Ongoing | Protection Management Research |

1.3 Determine the zone of low, medium and high disturbance for various human related activities near nesting sites in the boreal region and the Hudson Bay Lowlands.

|

Threats

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection Management Research |

1.4 Investigate the overlap between migration routes and areas of high wind energy

|

Threats

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection Management |

1.5 Develop guidelines for industries (for example wind power and mining), various development projects and recreational activity near Golden Eagle nests.

|

Threats

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection Management Research | 1.6 Evaluate levels of environmental contaminants in terrestrial and aquatic systems that could lead to bioaccumulation and/or death of Golden Eagles. |

Threats

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection Management Research | 1.7 Assess the cumulative impact of large obstructions (such as cell towers, large power transmission towers and wind turbines) within Golden Eagle migration routes. |

Threats

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection |

2.1 Develop a habitat description or habitat regulation to provide enhanced protection and clarity on the area defined as habitat for Golden Eagle in Ontario.

|

Threats

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection, Management |

2.2 Work with First Nation councils, municipalities and other planning agencies to identify and protect habitat including migration corridors, and populations through land use planning processes.

|

Threats

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment |

3.1 Investigate current standardized monitoring protocols or develop a standardized monitoring protocol specific to Ontario that outlines survey methods for continued monitoring at nesting and migration sites.

|

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment |

3.2 Continue to promote voluntary or citizen science programs throughout Ontario to further knowledge of migration areas and nesting sites

|

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Research |

3.3 Encourage and support collaboration of research activities that will increase knowledge of the eastern population of Golden Eagle in Canada and the United States.

|

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Communications, Research, Management |

3.4 Increase collaboration and communications with jurisdictions that co-manage the Eastern North America breeding population of Golden Eagles.

|

Threats

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Communications | 4.1 Translate all relevant Golden Eagle recovery, best management practices or policy documents into appropriate dialects of Cree and Ojibway. |

Threats

Knowledge Gaps

|

| Beneficial | Ongoing | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Education and Outreach Communications |

4.2 Develop communication/outreach tools to increase awareness and encourage reporting by agencies/individuals.

|

Knowledge Gaps

|

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the authors will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Golden Eagles rely on a variety of habitats for their survival, including nest site, nesting territory, foraging habitat and migratory corridors/stop-over areas (habitat used for resting, roosting and foraging during migration). Since nesting sites and the features on which they occur (cliff/tree), are critical to the survival of the species, it is recommended that the area prescribed as habitat for Golden Eagle be based on nest sites.

In Ontario, Golden Eagles have been found to nest primarily on cliffs, although they have been found to occasionally nest in trees (Sutherland 2007, NHIC 2013).

Golden Eagles are known to maintain multiple nests, which is thought to be important for courtship and pair bonding. Golden Eagles are also known to reuse nest sites, although the time between use is variable. In a study investigating Golden Eagle nest use over 45 continuous years, Kochert and Steenhof (2012) found 35 percent of nests were used only once, while 65 percent were used between 2 and 14 times.

Unused nests may be reused after decades of nonuse. Kochert and Steenhof (2012) found that out of 37 nests used more than once, 24 percent were last used 20 or more years prior to 2011 with some nests being reused or new nests built on top of former nests after 30 to 40 years of nonuse. In the United States there are recommendations that a seemingly unused nest site be protected for 10 years after the last known use (USFWS 2008). If the recommendation of protecting unused nests for 10 years after the last known use were followed it would not have protected 34 percent of all 300 nests that were reused during Kochert and Steenhof’s (2012) study and 49 percent of 37 reused nests monitored consistently for 41 years.

In Ontario it is not feasible for nests to be surveyed every year for evidence of use due to the remote areas where most known nesting sites occur (Armstrong et al. 2013; see Appendix A for suggested survey methods), making it challenging to protect nest sites simply on known nest use. Therefore, based on Kochert and Steenhof’s (2012) research, the fact that survey efforts for nests in Ontario are rare and infrequent, and the fact that cliff nesting sites may be limited, it is recommended that a nest site be defined as:

- nests that have been known to be occupied within the last 35 years;

- nests that have been identified as Golden Eagle nests within the last 35 years but have no previous record of occupation;

- newly discovered occupied nests;

- newly discovered unoccupied nests; and

- cliffs in habitat where there is evidence of Golden Eagle breeding behaviour (defined as “probable breeding” in Appendix A), so that sites are not prevented from receiving protection due to limitations of human search efforts and resources.

Given the importance and sensitivity of cliff habitat for nesting it is recommended that habitat for cliff nests should include the cliff face on which the nest rests, and extend vertically from the top of the cliff to the base and horizontally across the entire cliff face. It is important to include the entire cliff face given the understanding that it is important for Golden Eagles to build and maintain several nests within a breeding territory and that suitable nest sites are a limiting factor for this species. Alternate nests will be highly dependent on available and appropriate habitat within the breeding territory. In addition, there are currently fewer than 20 known pairs in Ontario; therefore this recommendation would result in the protection of a relatively small number of highly important habitat features for this species.

At sites where Golden Eagles nest in trees, it is recommended that regulated habitat should include the nest, the tree supporting the nest, and an area of protection around the tree itself. Vegetated buffer areas around nest trees help preserve strong, healthy root systems and minimize wind damage to the nest and supporting limbs (BC Ministry of Environment 2013). A common method used to measure the area of protection around a tree is to determine the critical root zone (CRZ) of a tree. The CRZ is an area defined as a circle with a diameter 24 to 36 times the diameter at breast height (DBH) of the tree, depending on the age and health of the tree (Dicke 2004, Johnson 1997).

White spruce trees in Ontario have a maximum known DBH of 60 cm (Sharma and Parton 2007, OMNR 2011b). Applying this method (36 (older trees) x 60 cm DBH), the recommended area protected around nest trees should be a circle with a diameter of 22 m.

Golden Eagles are dependent on foraging areas with abundant prey and conditions favourable for soaring and hunting (De Smet 1987). This species can be flexible in its use of habitats and will travel far from its nest to find good foraging habitat if habitat closer to their nests is less favourable (Marzluff et al. 1997). Golden Eagle home range sizes have been noted as ranging from 20 to 2,132 km² during the breeding season (Brodeur 1994, Kochert et al. 2002, Katzner et al. 2012a). Given the broad area of landscape used by Golden Eagle it is impractical and unnecessary to include foraging habitat in the area prescribed as habitat.

The use of habitats by Golden Eagles in Ontario outside of their breeding season is currently not well documented. Information is needed on stop-over areas (habitat used for resting, roosting and foraging) that are crucial for improving body condition, which is essential for the energetic demands required of Golden Eagles during migration between breeding and wintering grounds (see Section 1.7 Knowledge Gaps). In addition information needs to be gathered on potential migratory corridors in which Golden Eagles concentrate (e.g., along ecological barriers such as large water bodies) and tend to fly at low altitude (such as along ridges and coastlines). Once this information has been gathered, provisions should be made to incorporate any necessary information into the habitat regulation. Until then it is recommended that a habitat regulation focus on breeding habitat.

Glossary

- Axillaries:

- Feathers at the base of the underwing, also called ‘armpit’ or ‘wingpit’ (Clark and Wheeler 1987)

- Cere:

- A small area of bare skin above the beak of a bird.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC):

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO):

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank:

-

A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure - Coverts:

- The small feathers covering the base of the flight feathers and the tail.

- Dihedral:

- When wings are at an upward angle from horizontal.

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA):

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Orographic lift:

- When an air mass is forced from a low elevation to a higher elevation as it moves over rising terrain.

- Rotor-swept Zone:

- The area through which the rotor blades of a wind turbine spin, as seen when directly facing the center of the rotor blades.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA):

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario SARO) List:

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Stochastic Events:

- Unpredictable or random events such as earthquakes, floods, fires or droughts that can lead to fluctuations in population size.

- Thermals:

- A rising current of warm air.

References

Abbott, C.G. 1924. Period of incubation of the Golden Eagle. Condor 26:194. Amaral, M. and C. Gardner. 1986. A survey for cliff-nesting birds of prey along the Noatak River, Alaska. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage Fish and Wildlife Enhancement Endangered Species, Anchorage, AK.

Armstrong, T.E., L. Gerrish, J.W. Grier, and L. Skitt. 2013. Golden Eagle Survey in Red Lake District, 2008 – Northwest Region Species at Risk Draft Report. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Red Lake, Ontario. 20pp.

Asselin, N.C., M.S. Scott, J. Larkin, and C. Artuso. 2013. Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) breeding in Wapusk National Park, Manitoba. Canadian Field- Naturalist 127(2):180-184.

Bates, J.W. and M.O. Moretti. 1994. Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) population ecology in eastern Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 54:248-255.

Bednarz, J.C., D. Klem, Jr., L.J. Goodrich, and S.E. Senner. 1990. Migration counts of raptors at Hawk Mountain, Pennsylvania, as indicators of population trends, 1934-1986. Auk 107:96-109.

Bedrosian B., D. Craighead, and R. Crandall. 2012. Lead exposure in Bald Eagles from big game hunting, the continental implications and successful mitigation efforts. PLoS one 7(12):e51978. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051978.

Beebe, F.L. 1974. Field studies of the Falconiformes of British Columbia. British Columbia Provincial Museum Occasional Papers No. 17. 163 pp.

Begon, M., J.L. Harper, and C.R. Townsend. 1996. Ecology: Individuals, Populations and Communities. 3rd ed. Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK.

Bergo, G. 1987. Territorial behaviour of Golden Eagles in western Norway. British Birds 80:361-376.

Beecham, J.J. and M.N. Kochert. 1975. Breeding biology of the Golden Eagle in southwestern Idaho. Wilson Bulletin 87:506-513.

Bocharova N., G. Treu, G.A. Czirják, O. Krone, V. Stefanski, G. Wibbelt, E.R. Unnsteindóttir, P. Hersteinsson, G. Schares, L. Doronina, M. Goltsman, A.D. Greenwood. 2013. Correlates between feeding ecology and mercury levels in historical and modern Arctic Foxes (Vulpes lagopus). PLoS one 8(5):e60879. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060879.

Boeker, E.L. and T.D. Ray. 1971. Golden Eagle population studies in the Southwest. Condor 73:463-467.

BC Ministry of Environment. 2013. Guidelines for raptor conservation during urban and rural land development in British Columbia. http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/bmp/raptor_conservation_guidelines_2013.pdf Accessed March 2014.

Brodeur, S. 1994. Domaines vitaux et déplacements migratoires d’aigles royaux nichant dans la région de la baie d’Hudson au Québec. M.S. thesis, McGill University, Montreal.

Brodeur, S., R. Décarie, D.M. Bird, and M. Fuller. 1996. Complete migration cycle of Golden Eagles breeding in northern Quebec. Condor 98:293-299.

Brodeur, S. and F. Morneau. 1999. Rapport sur la situation de l’aigle royal (Aquila chrysaetos) au Québec. Société de la faune et des parcs du Québec, Direction de la faune et des habitats, Québec.

Brown, L. and D. Amadon. 1968. Eagles, hawks and falcons of the world. 2 volumes. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Inc.

Cadman, M.D., D.A. Sutherland, G.G. Beck, D. Lepage and A.R. Couturier. 2007. Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Ontario. Bird Studies Canada, Environment Canada, Ontario Field Ornithologists, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Nature. 728 pp.

Call, M. 1979. Habitat management guides for birds of prey. U.S. Bureau of Land Management Technical Note No. T/N-338. Denver, CO. 70 pp.

Clark, W.S. and B.K. Wheeler. 1987. A field guide to hawks in North America. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston, MA.

Collopy, M.W. 1984. Parental care and feeding ecology of Golden Eagle nestlings. Auk 101:753-760.

Craig, E.H. and T.H. Craig. 1998. Lead and mercury levels in Golden and Bald eagles and annual movements of Golden Eagles wintering in east central Idaho. 1990-1997. United States Department of Interior – Bureau of Land Management. Idaho State Office, Boise.

Craig, T.H., J.W. Connelly, E.H. Craig, and T.L. Parker. 1990. Lead concentrations in Golden and Bald eagles. Wilson Bulletin 102:130-133.

De Smet, K.D. 1987. Status report on the Golden Eagle, Aquila chrysaetos. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa, ON. 42 pp.

Dicke, S.G. 2004. Preserving trees in construction sites, Mississippi State University Extension Service. (http://msucares.com/pubs/publications/p2339.pdf).

Duerr A.E., T.A. Miller, M. Lanzone, D. Brandes, J. Cooper, et al. 2012. Testing an emerging paradigm in migration ecology shows surprising differences in efficiency between flight modes. PLoS one 7(4):e35548 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035548.

Dunstan, T.C., J.H. Harper, and K.B. Phipps. 1978. Habitat use and hunting strategies of Prairie Falcons, Red-tailed Hawks, and Golden Eagles. Final Report. Western Illinois University, Macomb.

Farmer, C.J., L.J. Goodrich, E. Ruelas Inzunza, and J.P. Smith. 2008. Conservation status of North America’s birds of prey. Pages 303–419 in State of North America’s Birds of Prey (K.L. Bildstein, J.P. Smith, E. Ruelas Inzunza, and R.R. Veit, eds.). Series in Ornithology, no. 3. Nuttall Ornithological Club, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

Franson, J.C., L. Sileo, and N.J. Thomas. 1995. Causes of eagle deaths. Pages 68 in Our living resources. (LaRoe, E.T., G.S. Farris, C.E. Puckett, P.D. Doran, and M. J. Mac, Eds.) U.S. Dep. Int., Natl. Biol. Serv. Washington, D.C.

Fyfe, R.W., and R R. Olendorff. 1976. Minimizing the dangers of nesting studies to raptors and other sensitive species. Canadian Wildlife Service, Occasional Paper 23. 17 pages.

Harmata, A.R. 1982. What is the function of undulating flight display in Golden Eagles? Raptor Research 16:103-109.

Harmata, A.R. and M. Restani. 1995. Environmental contaminants and cholinesterase in blood of vernal migrant Bald and Golden Eagles in Montana. Intermountain Journal of Science 1:1-15.

Hawk Migration Association of North America (HMANA). 2013. Data collection protocol. Available at http://hmana.org/. Accessed 19 Aug. 2013.

Hunt, W.G., R.E. Jackman, T.L. Hunt, D.E. Driscoll, and L. Culp. 1999. A population study of Golden Eagles in the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area; population trend analysis 1994-1997. Predatory Bird Research Group, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Hussell, D.J.T. and L. Brown. 1992. Population changes in diurnally-migrating raptors at Duluth, Minnesota (1974-1989) and Grimsby, Ontario (1975-1990). Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Wildlife Research Section, Maple.

Johnson, G. R. 1997. Tree preservation during construction: a guide to estimating costs. Minnesota Extension Service, University of Minnesota.

Katzner, T., B.W. Smith, T.A. Miller, D. Brandes, J. Cooper, M. Lanzone, D. Brauning, C. Farmer, S. Harding, D.E. Kramar, C. Koppie, C. Maisonneuve, M. Martell, E.K. Mojica, C. Todd, J.A. Tremblay, M. Wheeler, D.F. Brinker, T.E. Chubbs, R. Gubler, K. O’Malley, S. Mehus, B. Porter, R.P. Brooks, B.D. Watts, and K.L. Bildstein. 2012a. Status, biology, and conservation priorities for North America’s eastern Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) population. Auk 129:168-176.

Katzner, T.E., D. Brandes, T. Miller, M. Lanzone, C. Maisonneuve, J.A. Tremblay, R. Mulvihill and G.T. Merovich Jr. 2012b. Topography drives migratory flight altitude of golden eagles: implications for on-shore wind energy development. Journal of Applied Ecology 49:1178-1186.