Heart-leaved Plantain Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the Heart-leaved Plantain, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Jalava, J.V. and J.D. Ambrose. 2012. Recovery Strategy for the Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 27 pp.

Cover Illustration: Allen Woodliffe

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012

ISBN 978-1-4435-9425-7

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007, n'est disponible qu'en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Pamela Wesley au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Authors

Jarmo V. Jalava, Consulting Ecologist, Carolinian Canada Coalition

John D. Ambrose, Carolinian Woodlands Recovery Team

Acknowledgments

Earlier drafts of this recovery strategy were prepared in consultation with the Carolinian Woodlands Plants Technical Committee, consisting of Dawn Bazely (York University), Jane Bowles (University of Western Ontario), Barb Boysen (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, OMNR), Dawn Burke (OMNR), Peter Carson (Private consultant), Ken Elliott (OMNR), Mary Gartshore (Private consultant), Karen Hartley (OMNR), Steve Hounsell (Ontario Power Generation), Donald Kirk (OMNR), Daniel Kraus (Nature Conservancy of Canada), Nikki May (Carolinian Canada), Gordon Nelson (Carolinian Canada), Michael Peppard (Non government organization, NGO), Bernie Solymar (Private consultant), Tara Tchir (Upper Thames Conservation Authority), Kara Vlasman (OMNR), Allen Woodliffe (OMNR). Kate Hayes (Environment Canada / Savanta), Karen Hartley (OMNR), Chris Risley (OMNR) and Muriel Andreae (St. Clair Region Conservation Authority), who provided information and advice during the preparation of this strategy in its early stages. Michael Oldham (OMNR), Ron Gould (OMNR), Judith Jones (Winter Spider Eco-consulting) were especially helpful in the latter stages. Allen Woodliffe (OMNR) provided essential information and guidance throughout the development of the strategy.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Heart-leaved Plantain was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

The Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata) is a perennial herb that was first designated endangered in Ontario in 1985 because there are only two extant populations and they are limited by narrow habitat tolerance and ongoing habitat degradation. The global range originally extended across North America from Ohio, Ontario, Michigan and Minnesota, south to the southeastern United States, but the species is now extremely localized. The Canadian distribution has been reduced from seven historical populations to two extant locations near southern Lake Huron.

The extant Ontario Heart-leaved Plantain populations are found in rocky or gravely calcareous beds of shallow, slow moving clear streams or wet depressions. These streams or depressions are found in and shaded by relatively undisturbed low wet deciduous forests where ephemeral creeks flow in the spring and after heavy rains. Moisture is generally always present above or just below the soil surface. The species is limited by its specialized habitat requirements, the dynamic nature and limited availability of its habitat and its low reproductive output, high seedling mortality rate, limited dispersal ability and low genetic variation. Ontario populations are potentially threatened by removal of riparian vegetation, hydrological changes, degraded water quality, tree harvesting, munitions removal from a former military training area, collection for food and medicinal uses, invasive plant species and herbivory by invertebrates.

The recovery goal is to recover a self-sustaining, viable population of Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario. This will involve population viability analyses to determine if and the degree to which extant populations need to be enhanced, as well as the number and extent of additional populations that will need to be established in the species' historical range in southern Ontario. In order to meet this goal, the following protection and recovery objectives are recommended.

- Protect and manage habitat at extant sites in Ontario.

- Determine the size and number of extant sites (area of occupancy and area of extent), site quality, population health and population trends through inventory and regular monitoring.

- Address key knowledge gaps relating to minimum viable population size, habitat requirements and prioritization of threats.

- Where feasible, improve the viability of Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario by establishing populations at historical and other sites where suitable recovery habitat exists or can be restored.

- Promote awareness and stewardship of Heart-leaved Plantain to First Nations, land managers, private landowners, municipalities and other key stakeholders.

It is recommended that the area occupied by the plants be prescribed as habitat in a regulation, as well as an area of habitat surrounding the occupied area that is extensive enough to protect water quality and essential hydrological processes, allow for potential dispersal and population expansion, and maintain necessary moisture and light regimes. Specifically, the area prescribed should be a composite area delineated using the following three criteria: (i) a buffer of 120m from the outer limits of a population; (ii) a minimum buffer of 30 m along the watercourse and its tributaries upstream from a population; and (iii) the limit of the Ecological Land Classification community (ecosite) within which a population occurs.

Although historical sites were probably extirpated primarily due to habitat loss, there nevertheless appears to be suitable unoccupied habitat within its range in Ontario. It is therefore recommended that the habitat regulation be flexible enough to include sites for which introduction or reintroduction is planned. It should be noted that the species may spread through the dispersal of seeds or propagules downstream during flood events in the riparian habitats it occupies. The habitat regulation should therefore also allow for the inclusion of newly colonized sites. It is also recommended that populations cultivated for domestic or medicinal uses be excluded from the habitat regulation.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Heart-leaved Plantain

Scientific name: Plantago cordata

SARO List Classification: Endangered

SARO list history: Endangered (2008), Endangered – Regulated (2004)

COSEWIC assessment history: Endangered (2000), Endangered (1998), Endangered (1985)

SARA Schedule 1: Endangered (June 5, 2003)

Conservation status rankings: GRANK: G4 NRANK: N1 SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2. Species description and biology

Species description

Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata) is a perennial herb with fleshy, branching roots and a rosette of large, heart-shaped leaves at its base. It differs from other Ontario plantain (Plantago spp.) species in its having specialized fleshy roots and hollow flower stems (peduncles), and the major veins of the leaf arise from the nearby portion of the mid-vein as opposed to the base of the leaf. Individual plants have between 80 and 130 flowers, which grow on the upper 20 cm of the leafless stems. The 2.5 to 3.5 mm long dark brown seeds occur in two- to three-seeded capsules (Brownell 1998). Heart-leaved Plantain is the only semi-aquatic species of plantain in North America.

Species biology

Heart-leaved Plantain is a long-lived perennial, living up to seven years (Mackinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates 1994). Day length and temperature determine when leafing and flowering occur (Tessene 1969). Heart-leaved plantain blooms in mid-April in Ontario, as its flowering requires longer nights than daylight hours (Brownell 1998). The large, distinctive heart-shaped leaves are evident only in the summer since the plants produce morphologically distinct leaves that correspond to the seasons (NatureServe 2006). Smaller, narrower leaves are produced in the cooler seasons and the leaf production sequence can be arrested by stress conditions such as drought or high temperatures (Tessene 1969).

Flowers are normally wind-pollinated but are capable of self-pollination. Out-crossing is promoted by the fact that the pistil matures before the stamens allowing the plant to be fertilized by others in the vicinity (Brownell 1998). New plants are also capable of sprouting from the roots of a parent plant (Brownell 1998).

The species has relatively low reproductive output and limited seedling establishment (Mackinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates 1994). Seeds released in early summer adhere to each other by a gummy or gelatinous, buoyant placenta, allowing them to adhere to other floating objects and be dispersed elsewhere by water flow in the streambed (Brownell 1998). The short-lived seeds have only a few months to germinate after drying (Tessene 1969, Stromberg et al.1983, Brownell 1998). The average number of seed capsules per fruiting stalk is 86.4 (Brownell, 1998). Stromberg et al. (1983) found that the majority of seeds fell and germinated near the parent plants and that seedlings found on moist exposed clay banks were larger than any others at the site. Even for those that become established, seedling mortality is high. It has been observed that a large proportion of seedlings dies from herbivory or is swept away in floods (Stromberg et al. 1983).

The roots, fresh or dried, can be used in a tea to heal various ailments (Tessene 1969, NatureServe 2006) and the leaves have been used in poultices for burns and cuts (Moerman 1998). Steyermark (1963) states that Heart-leaved Plantain is the most tender of all the plantains when the young fleshy leaves and petioles are cooked.

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

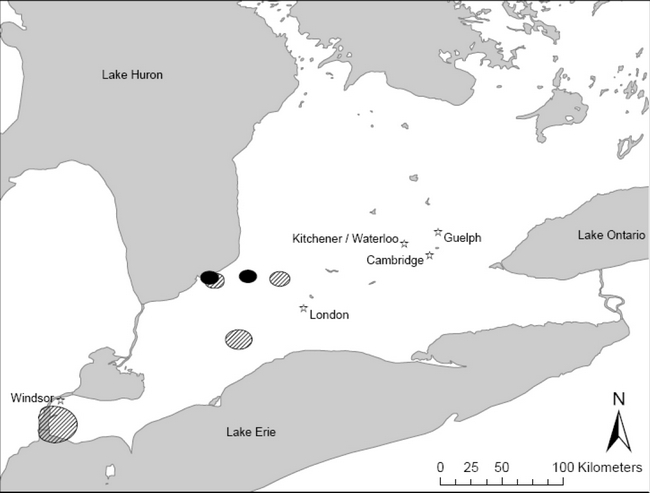

The global range of Heart-leaved Plantain originally extended across North America from Ohio, Ontario, Michigan and Minnesota, south to the southeastern United States. The species has been reported in 19 states and one province (Brownell 1998), but its populations are now very localized. There is a centre of abundance in Missouri and several isolated occurrences from eastern New York to northern Florida. The Canadian distribution has been reduced from at least seven to only two locations, both near the southern coast of Lake Huron. The five extirpated Canadian populations were near Thedford in Lambton County (last reported in 1967), Lucan and Glencoe in Middlesex, and Amherstburg and the Canard River in Essex (all of them last documented in the late 1800s) (Figure 1). Less than five percent of the global range and likely much less than one percent of the overall global population of Heart-leaved Plantain is in Canada.

This species has historically been collected by native peoples of eastern North America for food and medicinal uses. Much of its distribution appears to be correlated with the locations of important native cultural sites (Mymudes 1991); the Stony Point (also known as the "former Camp Ipperwash") site

The Stony Point populations in Lambton County, consisted of over 5,000 plants in 1993 (NHIC 2009). Out of a total of about 4,000 plants found there in 2009 (Damude pers. comm. 2010) 2,847 were found at previously undocumented locations (Rowland pers. comm. 2010). An estimated 90% of the plants counted in 2009 were mature (Sandilands and Mainguy pers. comm. 2011). These populations were found in linear depressions believed to be ephemeral ponds with no outflow, as well as along a small permanent stream (Damude pers. comm. 2010).

The Parkhill population in Middlesex County occurs at the headwaters of an ephemeral stream that is an upper tributary of the Ausable River. It consisted of approximately 1,600 mature plants and 1,500 seedlings during a site visit by Jalava in September 2008, whereas Jones (pers. comm. 2010) found 800 to 1,100 mature individuals and about 5,000 seedlings.

The Stony Point, Parkhill and historical Lucan and Thedford populations are all within the Ausable River watershed. The extirpated Glencoe occurrence was in the Thames River watershed, while the Amherstburg and Canard River populations were likely associated with Big Creek and the Canard River watersheds respectively.

Heart-leaved Plantain has a global rank of G4, meaning that it is apparently secure (NatureServe 2006). However no individual state or provincial jurisdiction considers the species secure. It has not been reported in more than 20 years in six states; it is considered extremely rare (S1) in nine states and very rare (S2) in one. Two states have ranked it as rare (S3), while it is considered rare to uncommon (S3S4) in Missouri. It remains unranked in South Carolina. The species is considered critically imperilled (N1 and S1) in Canada and Ontario. Populations have declined drastically throughout its range except for Missouri, where it appears to be relatively stable (Brownell 1983, Mymudes 1989, NatureServe 2006), although Mymudes and Les (1993) noted that even in Missouri, 15% of its populations have been extirpated.

Figure 1. Historical and Current Distribution of Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario (based on data from NHIC 2010). Solid areas represent extant occurrences, hatched areas represent historical occurrences and stars indicate city locations.

1.4 Habitat needs

Heart-leaved Plantain occupies stream channels or the emergent zone between open water and upland vegetation along stable, low-gradient streams and their adjacent floodplains. The emergent zone is characterized by seasonal flooding and gradual lowering of water levels, dense overstorey, and the absence of competing vegetation. This zone tends to shift temporally and spatially as stream channels undergo erosion and water level variations. The species appears to be able to adapt to minor shifts in habitat and channel location by colonizing suitable exposed habitats within the stream course. Heart-leaved Plantain depends on the presence of adequate moisture and a stable substrate for germination, seedling establishment and survival of young plants, and is usually absent where sediment, litter and debris suffocate seedlings or where canopy openings encourage colonization by other plant taxa. Microhabitat characteristics thus include adequate water levels that ensure sufficient moisture for roots and to periodically flush debris from the site (Mackinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates 1994).

The extant Ontario Heart-leaved Plantain populations are found in rocky or gravely calcareous beds of shallow, slow moving clear streams or wet depressions. These streams or depressions are found in and shaded by relatively undisturbed low wet deciduous forests where ephemeral creeks flow in the spring and after heavy rains. Moisture is generally always present above or just below the soil surface. The soil at the Stony Point site is clay loam with a pH of 7.2 (Brownell 1998), while the Parkhill population grows in soil described as "moist black muck" (NHIC 2009).

The dominant trees at the two extant Ontario sites are Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum), Silver Maple (A. saccharinum), Red Maple (A. rubrum), Blue-beech (Carpinus caroliniana), Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata), White Ash (Fraxinus americana), Black Ash (F. pennsylvanica) and Basswood (Tilia americana), along with Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) shrubs (Brownell 1998). Heart-leaved Plantain may be found with herb associates Swamp Buttercup (Ranunculus hispidus var. caricetorum), Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii), Water Pimpernel (Samolus valerandi ssp. parviflorus) and Fowl Manna Grass (Glyceria striata) (Brownell 1998) but plants are often found in areas with little other ground vegetation.

1.5 Limiting factors

Heart-leaved Plantain is limited by its specialized habitat requirements and the dynamic nature of its ephemeral streambed habitat. Heart-leaved Plantain also has the lowest reproductive output of all plantain species, possibly due to the allocation of resources into the broad leaves and fleshy thick roots which increase the probability of adult survival (NatureServe 2006). The high seedling mortality rate and dependence on the same mature individuals to reproduce each year makes the species especially vulnerable (Tessene 1969, NatureServe 2006). In one study, Stromberg et al. (1981) found that of 320 seedlings present in August only six survived until November. Bowles and Apfelbaum (1989) found that drought and runoff from heavy rainstorms limited distribution and establishment of seedlings and that storms may have contributed to 50% declines in seedling populations in 1986 due to flooding and erosion. These authors also noted "extremely high" seedling densities during low rainfall years. Adult plants can withstand stress such as drought or flooding for short periods, but if stressors persist for several seasons the adult population will not reproduce and will eventually be extirpated (Tessene 1969, NatureServe 2006).

Herbivory by native and non-native invertebrates, including slugs, snails, weevils, caterpillars and beetle larvae as reported by Mackinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates (1994), Stromberg et al. (1983) and Allen and Oldham (1984) may be a limiting factor.

The two extant populations of Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario are separated by more than 20 km, the vast majority of it being habitat unsuitable for colonization by the species. Small, geographically-isolated populations are prone to loss of genetic diversity and are at greater risk of being extirpated by a stochastic event. If they occur in habitat islands within a fragmented landscape as the Ontario populations do, their ability to disperse and colonize new sites is limited. The ability to colonize new sites is further restricted by the fact that seeds are normally dispersed by water in small, ephemeral, slow-moving streams, which in themselves are sparsely-distributed on the landscape. Most seeds germinate within one metre of the parent plant (Mackinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates 1994). A genetic study with samples from six states and Ontario found that there is very little genetic variation in the species, suggesting that genetic bottlenecks and founder effects have resulted from population crashes (Brownell 1998).

Even though most Heart-leaved Plantain populations are found in the shade of the deciduous forest, it is not clear to what degree the amount of solar radiation a population receives is a limiting factor. Tessene (1969) notes that some populations in New York and Illinois appeared to be doing well in full or partial sunlight. During a 2008 site visit to the Parkhill population, Jalava noted significantly higher numbers of flowering plants and densities of seedlings in a partially cleared portion of the occurrence than in the more densely-shaded unlogged sections. This was re-confirmed by Jones (pers. comm. 2010).

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Throughout its range, the major threats to Heart-leaved Plantain are cited as reduction to water quality due to upstream impacts such as clearing of riparian vegetation, industrial, agricultural and domestic run-off, and alterations to stream flow through ditching, draining and dams (Brownell 1998, CPC 2006, NatureServe 2006). Other widespread threats include on-site habitat destruction and isolation of populations resulting from land development, inappropriate forestry practices and grazing and trampling by cattle (Brownell 1998, CPC 2006, NatureServe 2006). Heart-leaved Plantain has also been collected for use as food and as a medicinal herb (Tessene 1969, NatureServe 2006, Moerman 1998, Steyermark 1963), including in Canada (Jalava et al. 2009). Removal of buried munitions from the Stony Point site may affect individual plants or their habitat (Rowland pers. comm. 2010). Low genetic diversity (Mymudes and Les 1993) and genetic isolation compound these threats to Ontario populations when combined with the above factors.

Suspected causes of extirpation at Ontario sites include local clearing of forest (Thedford, Amherstburg), flooding and scouring due to regional deforestation (Amherstburg, Canard River), cattle grazing and trampling (Thedford), loss of habitat (Glencoe, Amherstburg) and degradation of water quality (Amerherstburg, Canard River) (NHIC 2009). Each of the major threats to Ontario populations of Heart-leaved Plantain is qualitatively ranked in Table 1.

Table 1. Threat ranking for the two extant Ontario Heart-leaved Plantain populations

| Threats | Parkhill | Stony Point |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Nutrient-loading from agricultural run-off | High | Moderate |

| 2. Removal of riparian vegetation | High | Low |

| 3. Channeling and ditching | High | Low |

| 4. Inappropriate forestry practices | High | Low |

| 5. Invasive plants (e.g., Common Reed) | Unknown | High |

| 6. Development of roads and trails | Moderate | Low |

| 7. Munitions removal | n/a | Moderate |

| 8. Collecting for food or medicinal uses | Low | Moderate |

| 9. Herbivory by invertebrates | Unknown | Low |

Note: Severity of threat is qualitatively ranked High, Moderate, Low, Unknown or Not Applicable (n/a) at each site

Potential impacts on hydrology, water quality and light regime caused by vegetation removal, channeling, run-off and inappropriate forestry practices

Heart-leaved Plantain is extremely sensitive to declines in water quality (NatureServe 2006, Mymudes 1989) and is negatively affected by siltation and excessive nutrients (eutrophication). Nutrient-loading of streams from agricultural runoff can lead to eutrophication, stimulating algal growth with the resulting algal bloom preventing the short-lived seeds from reaching suitable germination substrates before they die (Stromberg and Stearns 1989, Stromberg et al. 1983).

Alterations to drainage caused by upstream or on-site ditching or channeling of streams affects the dynamics of the stream beds, reducing natural water fluctuations or diverting water flow and drying the habitat. The dynamic and variable nature of annual spring flooding allows the Heart-leaved Plantain habitat to change shape or position in the streams, minimizing the potential of colonization and competition for resources by plants that are less adapted to such specialized conditions (Bowles and Apfelbaum 1989, NatureServe 2006).

Clear-cutting or heavy selective logging affects the hydrology and water quality of woodland streams and results in higher water temperatures, increased erosion and siltation. Increased runoff increases the frequency and intensity of flooding and scouring of the stream bed. The siltation from the runoff results in mortality to adult plants and prevents seedling establishment. During floods, leaves have been shredded and entire plants have been uprooted (Meagher et al. 1978). Seedlings are especially vulnerable to uprooting (NatureServe 2006). Catastrophic flooding can eliminate a population unless sufficient numbers of reproducing plants survive in more sheltered areas to re-establish viable numbers (Bowles and Apfelbaum 1989). On the other hand, reduced water flow could result in populations being choked out as a result of succession by vegetation less well adapted to moderate flood cycles. Opening of the forest canopy also increases solar radiation, ground-level temperatures and rates of evapotranspiration, all of which may have a negative impact on Heart-leaved Plantain, which typically thrives in the shade of deciduous forests, even though the species has also been documented as growing in full sunlight (Tessene 1969).

There is probably little drainage from upstream areas affecting the Stony Point populations found in ephemeral ponds; however, the population along a permanent stream may be affected by run-off from agricultural fields south of Highway 21, as well as from the road itself. The Parkhill population, visited by Jalava in 2008, occurs in an ephemeral streambed in a deciduous forest. Some runoff from an adjacent agricultural field may occur into the streambed, particularly in spring and after heavy rains. Such run-off may contain silt, pesticides or pesticide residues. This small stream is part of the headwaters of the Hutchinson Drain, a tributary of lower Parkhill Creek. Most of the catchment surrounding the population is within the woodlot, which is contiguous with the Wright Tract, an Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority Agreement Forest.

Field observations therefore suggest that the water flowing through the low-lying areas occupied by the extant populations originates primarily from local snow-melt and rainfall. If this is the case then the main threat to the extant populations would be alteration of the woodland and riparian habitat in the immediate vicinity of the populations. It is possible that the two extant populations have persisted because of reduced upstream impacts on water quality and that some of Ontario’s other populations were extirpated because of such impacts. The extirpated population near Thedford does not appear to have been in a headwater area and would therefore have been more susceptible to upstream run-off.

Road and trail development and invasive species

The development of roads, trails and footpaths within and in the vicinity of Heart-leaved Plantain habitat increases the risk of invasion by and competition from introduced and invasive species. During a 2008 site visit, Jalava noted a significantly higher proportion of non-native and transitory or not fully established species in the portion of the Parkhill population bisected by a trail. Forestry operations also increase the likelihood of invasion by alien species through the transport of seeds on machinery, disturbance of soil and opening of the tree canopy, which may give a competitive advantage to light-tolerant weeds over shade tolerant forest species such as Heart-leaved Plantain.

Although not cited as a threat elsewhere, invasion of Heart-leaved Plantain habitat by the highly aggressive Eurasian variety of Common Reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis) may be a significant threat. This plant has invaded shorelines and wetlands throughout southwestern Ontario and is abundant in the Kettle Point – Stony Point – Port Franks area. Although Common Reed generally does not establish in shaded areas, it can colonize partly-shaded sites and has done so in the Kettle Point – Stony Point area at a number of locations (pers. obs.), although not in the vicinity of Heart- leaved Plantain habitat (Sandilands and Mainguy pers. comm. 2011).

Collecting for food and medicinal uses

According to Monague (pers. comm. 2010) Heart-leaved Plantain is not currently being harvested for food or medicinal uses at the Stony Point site. If harvested indiscriminately, this activity could potentially have a serious impact on the viability of a population.

Herbivory by invertebrates

Herbivory by native and non-native invertebrates, including slugs, snails, weevils, caterpillars and beetle larvae, has been identified as a significant threat to Heart-leaved Plantain populations (Mackinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates 1994). Allen and Oldham (1984) report holes in the leaves or with leaves severed at the petiole due to invertebrate herbivory. The introduced pest Gray Garden Slug (Deroceras reticulatum) is cited as having caused significant damage to mature leaves at the Camp Ipperwash population (Mackinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates 1994) but there is no indication that the slugs were definitively identified by a malacologist. In 1988, it was noted that virtually all plants at the Parkhill population showed evidence of herbivory by "some form of leaf-mining larvae," which were reared to maturity and found to be beetles of the family Chrysomelidae (Dibolia borealis), a common species of flea beetle associated with several species of plantain (Anonymous 1988, citing L. Lesage pers. comm. of the Biosystematics Research Centre, Ottawa). This beetle can cause extensive damage to leaves of the host plant, but not enough to kill the plant. However, observations in 2008 and 2009 by Sandilands and Mainguy (2011), Jones (2009) and Jalava (2008) were of generally healthy-looking plants with little or no herbivory noted.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Knowledge gaps that may limit the successful recovery of the Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario include:

- the precise extent of habitat at extant sites;

- causes of extirpation at historical sites;

- whether additional areas of suitable habitat support the species in Ontario;

- the effects of water quality and changes in the hydrologic regime on habitat dynamics at Ontario sites (requires hydrological and geomorphological characterization);

- better understanding and prioritization of threats;

- demographics and biology of the species (e.g., minimum viable population levels, specific habitat needs, pollination and dispersal);

- understanding propagation and establishment requirements before introduction into historical sites or new habitats is considered.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Periodic surveys have been made of the two extant populations in Ontario. Survey results are presented in the COSEWIC status report (Brownell 1998).

A management plan for Heart-leaved Plantain was prepared for the Department of National Defence (DND) in 1993 when the site was being operated as Camp Ipperwash (Hensel Design Group 1993, NHIC 2009). The Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point hosted a visit by Environment Canada and DND staff in 2007 to evaluate the potential impacts of munitions removal from the site. National Defence Canada is currently surveying the area for unexploded ordnances and is accompanied by a biologist who is doing population counts and georeferencing species at risk populations (Damude pers. comm. 2010). As a result, fine scale, accurate mapping of the Heart-leaved Plantain population has been produced, although the 2010 survey report was not available at the time of writing. The Kettle and Stony Point First Nation communities are generally cognizant of the presence, location and significance of the population (George pers. comm. 2008, Monague pers. comm. 2010). According to Monague (2010), there is currently little or no visitation of the site or disturbance of the population by band members or anyone else.

Ownership of the property supporting the Parkhill population has changed hands more than once since initial site visits by OMNR in 1987. It has been periodically visited by OMNR staff with permission from existing landowners (Woodliffe pers. comm. 2009). The habitat was mapped in 1998 for the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program.

Jalava contacted the current owner in 2008 and was granted permission to access. The landowner was aware of the location and condition of the population and even noted that there had been some selective logging nearby. Canadian Wildlife Service contracted survey work at the site in 2010 and updated population counts and georeferencing was produced (Jones pers. comm. 2010). The landowner indicated to Jones (pers. comm. 2010) that he had no intentions of doing further logging in the vicinity of the Heart-leaved Plantain population and that he had no issues with protection of the habitat.

A Conservation Action Plan for the Ausable River – Kettle Point to Pinery area includes Heart-leaved Plantain as one of its top priority conservation targets (Jalava et al. 2009). The lead agency on this initiative is the Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority which has indicated intent to work with the landowner to protect the Parkhill population. The Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation have also expressed an interest in conserving the Stony Point population (George pers. comm. 2008) and have contributed to the development of the action plan. Implementation is underway with multiple partners including the First Nation, Carolinian Canada Coalition, the Lake Huron Centre for Coastal Conservation, the St. Clair Region Conservation Authority and with support from the federal Aboriginal Funds for Species At Risk program. This Conservation Action Plan is an initiative of the Carolinian Canada Coalition through partnership with OMNR and Environment Canada.

Carolinian Canada Coalition prepared a draft "best management practices" fact sheet for Heart-leaved Plantain in 2011-2012 and will be providing this to relevant stakeholders and landowners.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal is to recover a self-sustaining, viable population of Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario. This will involve population viability analyses to determine if and the degree to which extant populations need to be enhanced, as well as the number and size of additional populations that will need to be established in the species' historical range in southern Ontario.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 2. Protection and Recovery Objectives

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | Protect and manage habitat at extant sites in Ontario. |

| 2.0 | Determine the size and number of extant sites (area of occupancy and area of extent), site quality, population health and population trends through inventory and regular monitoring. |

| 3.0 | Address key knowledge gaps relating to minimum viable population size, habitat requirements and prioritization of threats. |

| 4.0 | Where feasible, improve the viability of Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario by establishing populations at historical and other sites where suitable recovery habitat exists or can be restored. |

| 5.0 | Promote awareness and stewardship of Heart-leaved Plantain with First Nations, land managers, private landowners, municipalities and other key stakeholders. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 3. Specific Approaches to Recovery for the Heart-leaved Plantain

- Objective: Protect and manage habitat at extant sites in Ontario

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection | 1.1 Identify the positive and/or negative impacts of land-use and management practices, both on- site and in adjacent areas that may have an impact on habitat and water quality. | Threats: removal of riparian vegetation; channeling and ditching; nutrient-loading from agricultural runoff; water pollution from domestic and industrial run-off; roads, trails and land development; inappropriate forestry practices; recovery of munitions; invasive species; livestock grazing. |

| Critical | Short-term | Management | 1.2 Develop Best Management Practices (BMPs), including guidelines for appropriate forest and watershed management and compatible upstream agricultural practices within the watersheds of extant populations by:

| Threats: removal of riparian vegetation; channeling and ditching; nutrient-loading from agricultural runoff; water pollution from domestic and industrial run-off; roads, trails and land development; inappropriate forestry practices; recovery of munitions; invasive species; livestock grazing. |

| Critical | Short-term | Stewardship | 1.3 Provide recommendations and BMPs to municipalities, conservation authorities, appropriate government ministries (e.g., MNR, OMAFRA, MOE, DFO and DND), adjacent landowners, private land site stewards, First Nation council members and land managers. | Threats: removal of riparian vegetation; channeling and ditching; nutrient-loading from agricultural runoff; water pollution from domestic and industrial run-off; roads, trails and land development; inappropriate forestry practices; recovery of munitions; invasive species; livestock grazing. |

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection | 1.4 Regulate the habitat of Heart-leaved Plantain and work cooperatively with stakeholders, First Nations, the Government of Canada and the Government of Ontario to ensure habitat is protected. | Threats: removal of riparian vegetation; channeling and ditching; nutrient-loading from agricultural runoff; water pollution from domestic and industrial run-off; roads, trails and land development; inappropriate forestry practices; recovery of munitions; invasive species; livestock grazing. |

| Beneficial | Long-term | Protection | 1.5 Identify and secure key sites in the context of the overall Carolinian Woodlands Recovery Strategy (Jalava et al. 2008, Jalava and Mansur 2008) through conservation easements, stewardship agreements or acquisition. | All threats. |

2. Objective: Determine the size and number of extant sites (area of occupancy and area of extent), site quality, population health and population trends through inventory and regular monitoring.

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.1 Inventory all areas of suitable habitat along streams having historical reports of Heart-leaved Plantain. | Knowledge gaps: better understanding of current distribution and population size; causes of extirpation at historical sites. |

| Necessary | Short-term | Research | 2.2 Identify and survey additional sites with apparently suitable habitat including areas downstream from the Parkhill population. | Knowledge gaps: current status. All threats |

| Beneficial | Short-term | Research | 2.3 Review herbarium collections of other broad- leaved plantain (Plantago spp.) species to determine if some may have been misidentified specimens of Heart-leaved Plantain. | Knowledge gaps: potential for discovery of additional historical and extant sites. |

| Necessary | Ongoing | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.4 Develop and apply monitoring protocol in association with monitoring other priority species of the overall Carolinian Woodlands Recovery Strategy (Jalava et al. 2008, Jalava and Mansur 2008). | All threats. Knowledge gaps: better understanding of current status. |

3. Objective: Address key knowledge gaps relating to minimum viable population size, habitat requirements and prioritization of threats.

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 3.1 Rigorously assess habitat needs and threats based on surveys and monitoring at extant sites. | All threats. Knowledge gaps: better understanding of habitat needs and prioritization of threats; invasive species impacts |

| Necessary | Long-term | Research | 3.2 Conduct population viability analysis. | Knowledge gap relating to minimum viable population level |

| Necessary | Short-term | Research | 3.3 Determine, through interviews with appropriate individuals if Heart-leaved Plantain is currently being collected. | Threat: collecting for food or medicinal purposes. |

| Necessary | Short-term | Research | 3.4 Conduct hydrological study at extant sites to better understand hydrological influences on habitat. | All threats relating to hydrology and water flow. Knowledge gaps relating to hydrology and habitat requirements. |

| Necessary | Long-term | Research | 3.5 Engage academic community to investigate:

| Knowledge gaps relating to pollination, dispersal, and viability of small isolated populations. |

4. Where feasible, improve the viability of Heart-leaved Plantain in Ontario by establishing populations at historical and other sites where suitable recovery habitat exists or can be restored.

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 4.1 Determine feasibility of restoration or rehabilitation of habitat at historical occurrences. | All threats. Knowledge gaps: causes of extirpation at historical sites; is there suitable habitat for reintroduction? |

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 4.2 Develop restoration plans, including timelines and costs. | All threats. |

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 4.3 Improve the size and health of extant populations through restoration and by assisting in the spread and planting of seed produced at these sites. | All threats. |

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 4.4 Integrate restoration planning and activities with CAP initiative and other programs of partner agencies and groups (e.g., Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority, Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation, OMNR, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Society for Ecological Restoration, DND). | All threats. |

| Beneficial or Necessary | Long-term | Stewardship | 4.5 Based on assessments of threats, studies of the species' biology and ecology and population viability analysis, determine the feasibility and necessity of reintroduction. | All threats. |

| Beneficial or Necessary | Long-term | Stewardship | 4.6 Reintroduce species to historical or other suitable sites, if deemed feasible. | All threats. |

5. Objective: Promote awareness and stewardship of Heart-leaved Plantain to First Nations, land managers, private landowners, municipalities and other key stakeholders.

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Short-term | Education Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Outreach Communications | 5.1 Develop outreach materials that highlight the significance, vulnerability and threats to Heart- leaved Plantain, emphasizing the major threats and how to best address or mitigate them. | All threats. |

| Necessary | Short-term | Education Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Outreach Communications | 5.2 Disseminate these materials to Chief and Council and other interested members of the Kettle and Stony Point First Nation, conservation authorities, land owners, municipal planners, stewardship councils and other key stakeholders. | All threats. |

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

The high level of sensitivity of Heart-leaved Plantain to changes in its specialized semi-aquatic habitat suggests that the most crucial management need is to control the factors that would adversely affect water quality, water level fluctuations (NatureServe 2006), and the woodland habitat in the vicinity of the populations. This will involve engaging the broader community that influences the quality of the watersheds in which the endangered species occurs. Key partners will be the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation, private landowners, Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority, National Defence Canada and municipalities.

Because of the isolation of the two extant populations from other sites with suitable habitat, it is unlikely that the recovery of Heart-leaved Plantain will be possible in Ontario without human intervention. With so much of its historical range under intensive agriculture, and the associated high levels of fertilizer run-off, siltation, tile drainage, and ditching and channeling of streams, the availability of high-quality habitat may be the main limiting factor for this species. Habitat in the vicinity of extant occurrences will need to be restored and water quality improved for natural establishment of satellite populations to occur. Given the extent of land conversion within the species' historical range, opportunities for re-establishment of populations elsewhere in its former range are limited but some historical sites may be restorable. Re-introduction will require addressing the complexity of impacts that degraded such sites in the first place.

A population viability analysis is recommended in order to better quantify population targets for successful recovery. In such an analysis, variation in demographic parameters such as survivorship, growth and fecundity are measured over several years, providing predictions of future population dynamics including the probability of extinction, based on our understanding past environmental conditions and estimated rates of natural catastrophes (Menges 1990).

Habitat regulation is recommended for Heart-leaved Plantain in order to better define the areas that need to be protected to ensure the survival and recovery of populations based on the relevant biological, ecological and hydrogeological considerations. The specific area that is recommended to be prescribed as habitat in a regulation for Heart- leaved Plantain is included in section 2.4 of the recovery strategy.

Heart-leaved Plantain can be propagated from seed and be re-established in suitable sites (NatureServe 2006) if its specialized habitat conditions can be restored. Seeds readily germinate in their natural habitats and direct seeding might be another approach. In order to improve water quality and maintain consistent water flow levels, restoration efforts should focus on reducing erosion, siltation and pulse runoff from stochastic storm events through establishing upland vegetation in upstream areas (Bowles and Apfelbaum 1987, 1988, 1989).

It is recommended that coordination of recovery activities be undertaken in concert with the Carolinian Woodland Recovery Strategy (Jalava et al. 2008, Jalava and Mansur 2008) and the associated Ausable River – Kettle Point to Pinery Conservation Action Plan (ARKPP CAP) (Jalava et al. 2009), which are broader, ecosystem-based implementation strategies designed by a diverse group of stakeholders and experts to benefit a broad range of species at risk including Heart-leaved Plantain. The ARKPP CAP is linked to other large-scale conservation initiatives relevant to recovery efforts for Heart-leaved Plantain such as the Ausable River Aquatic Ecosystem recovery strategy, the Natural Spaces program and the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s Conservation Blueprint. Collaborative and well-coordinated efforts improve efficiency and information-sharing and reduce duplication of efforts amongst groups, agencies and organizations that have common goals.

2.4 Performance measures

Measures of the success of the recovery effort should form part of the regular monitoring program. Measures should include long-term trends in the size and number of extant sites (area of occupancy and area of extent), site quality (measured through a habitat suitability index) and population trends and projections determined through regular population counts. A scoring system should be developed that will allow for quantitative comparisons between Heart-leaved Plantain populations and factors affecting the quality and extent of its woodland habitat.

Monitoring may be undertaken at varying levels of intensity in the future depending on the current threat level, size and quality of each site. The following criteria are based in part on monitoring methods recommended in Bickerton (2003) and NatureServe (2006).

- A less-intensive level of monitoring may be undertaken by volunteers or landowners annually or biannually. Performance measures would include the presence or absence of Heart-leaved Plantain and an approximate population count, a coarse numerical assessment of threats and qualitative assessment of changes to habitat quality and threats.

- A more intensive level of monitoring may involve demographic monitoring of the Heart-leaved Plantain population trend based on life stages, seedling- establishment, mortality and other factors. Intensive monitoring may be considered for critical sites with a high-level of threat, sites for which qualified staff are available to conduct annual monitoring and any re-introduction sites. Populations should be monitored to assess stability, note recruitment, document longevity of individuals and to note the yearly reproductive output of individual plants. Downstream migration should also be monitored. Monitoring water quality and stream flow along with population counts may provide some useful correlations on the quality of the habitat and the stability of the population. Monitoring water quality should include noting evidence of nutrient loading, algal blooms, turbidity and levels of dissolved oxygen (NatureServe 2006).

With Heart-leaved Plantain’s viability in Canada so uncertain, both extant populations should receive the more intensive level of monitoring, restoration and direct seeding.

Evaluation of the overall recovery effort should be measured by the following criteria.

- No loss of individual plants in extant populations. Extant populations are increasing or stable in size;

- Habitat identified and mapped, and a habitat regulation developed, by 2015;

- Communications products produced and distributed to landowners and land managers starting in 2012;

- Historical reports and other potential habitat comprehensively surveyed by 2012;

- Potential restoration sites identified by 2013;

- No increase in anthropogenic disturbance (as determined from monitoring data) and threats being addressed by 2013;

- Habitat restoration initiated by 2014; and

- Where feasible, reintroduction initiated at suitable or restored historical sites by 2016.

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the authors will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Heart-leaved Plantain has a very limited distribution in Ontario with only two known extant occurrences. Given that the species does not occupy all apparently suitable habitat, it is suggested that the area occupied by the plants be prescribed as habitat in a regulation, as well as an area of habitat surrounding the occupied area that is extensive enough to protect water quality and essential hydrological processes. It should also allow for potential dispersal and population expansion and maintain the necessary moisture and light regimes for the species to thrive.

The area prescribed as habitat in a regulation for Heart-leaved Plantain should be a composite area delineated using the following three criteria:

- a buffer of 120 m

footnote 3 from the outer limits of a population (OMNR 2002) - a minimum buffer of 30 m

footnote 4 along the watercourse and its tributaries upstream from a population (Environment Canada 2010); and - the limit of the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) vegetation community (ecosite) (Lee et al. 1998) within which a population occurs.

Any new information on the species' habitat requirements and site-specific characteristics (such as hydrology) should also be considered. In particular, if it is demonstrated that a larger or smaller area is necessary (or adequate) to protect the hydrological regime upon which the species depends, the habitat regulation should be revised to reflect this.

Although historical sites were probably extirpated primarily due to habitat loss, there nevertheless appears to be suitable unoccupied habitat within the species' range in Ontario. It is therefore recommended that the habitat regulation be flexible enough to include sites for which introduction or reintroduction is planned. It should be noted that the species may spread through the dispersal of seeds or propagules downstream during flood events in the riparian habitats it occupies. The habitat regulation should therefore also allow for the inclusion of newly colonized sites.

Heart-leaved Plantain is occasionally cultivated for domestic or medicinal uses. It is recommended that such horticultural populations be excluded from the habitat regulation.

Glossary

Calcareous: refers to limestone or lime-rich soils.

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

Ecological Land Classification (ELC): The Ecological Land Classification system for Ontario (Lee et al. 1998) is a standardized method for describing and categorizing the patterns of distribution and assemblage of vegetation based on moisture, soils, geology, landform and climate, at different scales.

Ecosite: Ecosite is a mappable landscape unit defined by a relatively uniform parent material, soil and hydrology, and consequently supports a consistently recurring formation of plant species which develop over time. The Vegetation Type is a finer unit, part of an ecosite, and represents a specific assemblage of species which generally occur in a site with a more uniform parent material, soil and hydrology, and a more specific stage of natural succession. (NHIC 2009; Lee et al. 1998)

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Ephemeral: Refers to streams and ponds that are flooded in spring and after heavy rains, but which normally dry up in summer.

Founder effect: In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population.

Petiole: The stem portion of a leaf.

Propagule: A propagule is any plant material used for the purpose of plant propagation, such as bulb, seed, spore or stem (that can take root).

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

Stochastic event: A random environmental event, such as a flood, drought, collapse of a streambank, plague of insects, etc.

References

Aazhoodena and George Family Group. 2006. Aazhoodena: The History of the Stony Point First Nation. Project of the Aazhoodena and George Family Group for the Ipperwash Inquiry, June 30, 2006. 47 pp. PDF document (accessed September 12, 2010).

Allen, G.M. and M.J. Oldham. 1984. Update to Brownell, V.R. 1983. Status Report on the Heart-leaved Plantain, Plantago cordata, COSEWIC, Ottawa.

Anonymous. 1988. Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata) in Ontario, an Update. Manuscript on file, Natural Heritage Information Centre, Peterborough. 4 pp.

Argus, G.W., K.M. Pryer, D.J. White, and C.J. Keddy. 1982-87. Atlas of the Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario. 4 parts. National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa, Ontario. Looseleaf.

Bickerton, H. 2003. (Draft) Monitoring Protocol for Pitcher’s Thistle (Cirsium pitcheri) – Dune Grasslands. Pitcher’s Thistle – Lake Huron Dune Grasslands Recovery Team. Manuscript.

Bowles, M. and S. Apfelbaum. 1987. A report to the Illinois Endangered Species Protection Board on the Population Status, Ecology, and Management Needs of the Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata Lam.) at the Mackinaw River Recreation Area, Tazewell County, Illinois.

Bowles, M. and S. Apfelbaum. 1988. Factors affecting survival and decline of the Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata Lam.) in gravel-bed stream habitat. Natural Areas Journal 9(2) 90-101.

Bowles, M. and S. Apfelbaum. 1989. Effects of land use and stochastic events on the Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata Lam.) in an Illinois stream system. Proceedings of the 15th Annual Natural Areas Conference: Ecosystem Management, Rare Species and Significant Habitats, June 6-9, 1988, Syracuse, New York.

Brownell, V.R. 1983. Status Report on the heart-leaved Plantain, Plantago cordata, COSEWIC, Ottawa, with an up-date by G.M. Allen and M.J. Oldham, 1984.

Brownell, V.R. 1998. Update COSEWIC status report on the heart-leaved plantain Plantago cordata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa. [modified by E. Haber 2000]

Castelle, A.J., A.W. Johnston and C. Conolly. 1994. Wetland and stream buffer size requirements – a review. Journal of Environmental Quality 23:878-882.

Champion, B., V. Jarrin, D. Baughman and P. Gervais. 2009. Buffer widths and alternative methods for water quality protection in water supply watersheds. Proceedings of the 2009 Georgia Water Resources Conference, held April 27-29, University of Georgia. On-line document:http://www.gwri.gatech.edu/uploads/proceedings/2009/3.4.4_Champion.pdf [link inactive]

CPC (Center for Plant Conservation) 2006. Restoring America’s Native Plants, CPC National Collection Plant Profile, Plantago cordata. On-line document: http://www.centerforplantconservation.org/ASP/CPC_ViewProfile.asp?CPCNum=3509 [link inactive]

Damude, D. 2010. Personal communication with J. Jalava, September 16, 2010. Environmental Project Officer, Department of National Defence, Ottawa.

Environment Canada. 2005. Species at Risk web page for Heart-leaved Plantain, Plantago cordata. On-line document: http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=181

Environment Canada. 2010. Great Lakes Fact Sheet: How Much Habitat is Enough? Second Edition. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario Region. On-line document: http://www.on.ec.gc.ca/wildlife/factsheets/fs_habitat-e.html [link inactive]

George, G. Personal communications with J. Jalava and Ausable – Kettle Point to Pinery Conservation Action Plan (CAP) Team, October 1-3, 2008. Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation former Band Councilor and CAP Team representative.

Hensel Design Group Inc. 1993. Protection and management plan for heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago Cordata Lam.) on camp Ipperwash. Department of National Defence. 25 pp.

Jalava, J.V. and P. Mansur. 2008. National Recovery Strategy for Carolinian Woodlands and Associated Species at Risk, Phase II: Part 1 – Implementation. Draft 5, September 30, 2008. Carolinian Canada Coalition, London, Ontario. vii + 124pp.

Jalava, J.V., J.D. Ambrose and N. S. May. 2008. National Recovery Strategy for Carolinian Woodlands and Associated Species at Risk: Phase I. Draft 10 – March 31, 2008. Carolinian Canada Coalition and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, London, Ontario. viii + 75 pp.

Jalava, J.V., M. Andreae, J.M. Bowles, G. George, K. Jean, A. MacKenzie, M. McFarlane and P. Scherer. 2009. Ausable River – Kettle Point to Pinery Conservation Action Plan (CAP). The Ausable River – Kettle Point to Pinery Conservation Action Planning Team (Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority, Carolinian Canada Coalition, University of Western Ontario, Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation, Ontario Parks, Nature Conservancy of Canada, Municipality of Lambton Shores, Lambton Federation of Agriculture). viii + 75 pp.

Jones, J. 2010. Personal communications with J. Jalava, September 16, 2010. Ecological consultant (Winter Spider Eco-consulting) on contract with Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario Region.

Lee, H., W. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application. SCSS Field Guide FG-02. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 225 pp.

MacKinnon Hensel Mackinnon Hensel & Associates 1994 Associates. 1994. Protection and Management Plan for Heart-leaved Plantain (Plantago cordata Lam.) on Camp Ipperwash, Final Report, submitted to Department of National Defence.

Meagher, T.R., J. Antonovics and R. Primack. 1978. Experimental ecological genetics in plantago. III. Genetic variation and demography in relation to survival of Plantago cordata, a rare species. Bio. Conserv. 14(4):243-258.

Menges, E. 1990. Population Viability Analysis for an Endangered Plant. Conservation Biology 4(1):52-62.

Moerman, D. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press, Portland, OR. 927 pp.

Monague, B. 2010. Personal communication with J. Jalava (September 15, 2010). Member of the Band Council, Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation.

Mymudes, M. 1989. Personal correspondence with D. McLeod of Aylmer District, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, including draft research paper on Plantago cordata, as presented to Wisconsin Botanical Club, April 29, 1989.

Mymudes, M. 1991. Morphological and genetic variability in Plantago cordata Lam. (Plantaginaceae), a rare aquatic plant. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, MSc Dissertation.

Mymudes, M. and D. H. Les. 1993. Morphological and genetic variability in Plantago cordata (Plantaginaceae), a threatened aquatic plant. American Journal of Botany 80(3): 351-359.

NatureServe. 2006. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 6.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed: November 10, 2006 ).

NHIC (Natural Heritage Information Centre). 2009. Species Lists, Element Occurrence and Natural Areas databases and publications. Natural Heritage Information Centre, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. Electronic databases.

NYFA (New York Flora Association of the New York State Museum Associates). 1999. NYFA Newsletter, April 1999, Vol. 10, No. 1.

OMNR (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources). 2002. Ontario Wetland Evaluation System, Southern Manual, covering Hill’s Site Regions 6 and 7. Third Edition, revised December 2002. MNR Warehouse #50254-1.

Rowland, J. 2010. Personal communication with J. Jalava, June 2010. Species at Risk Officer, Directorate of Environmental Stewardship 4-3, Director General Environment, National Defence, National Defence Headquarters, Ottawa.

Sandilands, A. and S. Mainguy. 2011. Personal communications (e-mail correspondence between Al Sandilands and Sarah Mainguy, observers of Stony Point Heart-leaved Plantain populations in 2009, and Ruben Boles, Environment Canada, July-September 2011, re: review of draft federal recovery strategy for Heart-leaved Plantain).

SARA Public Registry, Species Profile: Heart-leaved Plantain http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=181

Steyermark, J.A. 1963. Flora of Missouri. The Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA. 1728 p.

Stromberg, J. and F. Stearns. 1989. Plantago cordata in Wisconsin. Michigan Botanist 28: 3-16.

Stromberg, J., M. Kunowski and F. Stearns. 1981. Plantago cordata Lam. In southeastern Wisconsin: ecology, reproduction, and development of a management plan. Progress report. Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. 20 pp.

Stromberg, J., M. Kunowski. and F. Stearns. 1983. Preservation and Introduction of Heart-shaped plantain (Wisconsin). Restoration and Management Notes. 1, 304: 29.

Tessene, M.F. 1969. Systematic and ecological studies on Plantago cordata. The Michigan Botanist, Vol. 8, 72-101.

Woodliffe, P.A. 2009. Personal communications with J. Jalava, February – March 2009. District Ecologist, OMNR Aylmer District, Chatham Area Office, Chatham, Ontario.

Recovery strategy development team members

The recovery strategy was developed by Jarmo Jalava and John Ambrose under the direction of the following recovery team members:

| Name | Affiliation and location |

|---|---|

| Roxanne St. Martin (Co-chair) | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Michelle Kanter (Co-chair) | Carolinian Canada Coalition |

| Dawn Bazely | York University |

| Jane Bowles | University of Western Ontario |

| Barb Boysen | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Dawn Burke | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Peter Carson | Private Consultant / Ontario Nature |

| Ken Elliott | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Mary Gartshore | Private Consultant |

| Ron Gould | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Karen Hartley | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Steve Hounsell | Ontario Power Generation |

| Jarmo Jalava | Carolinian Canada Coalition |

| Donald Kirk | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Daniel Kraus | Nature Conservancy of Canada |

| Nikki May | Carolinian Canada |

| Gordon Nelson | Carolinian Canada Coalition / University of Waterloo |

| Michael Oldham | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Michael Peppard | Conservation organization (NGO) |

| Jennifer Rowland | Department of National Defence |

| Bernie Solymar | Private Consultant |

| Tara Tchir | Upper Thames River Conservation Authority |

| Kara Vlasman | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Allen Woodliffe | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph The land of the Stony Point First Nation was appropriated by the Federal Government in 1942 for use as a military training area known as Camp Ipperwash, with the promise that the lands would be returned after World War II. Camp Ipperwash ceased operation as a military base in 1993. Negotiations are currently underway to re-establish Stony Point First Nation #43 (Azhoodena and George Family Group 2006). According to Rowland (pers. comm. 2010) and Damude (pers. comm. 2010), the land at Ipperwash is presently National Defence Canada land or Federal Land and the process of removing unexploded ordnances is ongoing and will take several years. With time the area is to be transferred to Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Day-to-day guardianship management of the site has been contracted to members of the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation who are awaiting a land claim settlement over the 1942 Ipperwash appropriation. According to Monague (pers. comm. 2010), access to the site is an issue in the community and that for the time being no one is entering the areas supporting the Heart-leaved Plantain population. Survey work was conducted by DND at the site in 2009 and 2010 (Damude pers. comm. 2010). [It should be noted that the spellings of the name Stony / Stoney differ depending on whether one is referring to the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation or the Stoney Point First Nation.]

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Currently there is only one extant population on private land and one on First Nation land. However, if additional populations are discovered through inventory or if suitable habitat for reintroduction is found, these might also be priority sites for acquisition or conservation easements.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Heart-leaved Plantain is a wetland species and the recommended 120 m buffer is consistent with policy protecting adjacent lands of provincially significant wetlands (OMNR 2002)

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph This is the average minimum riparian buffer width recommended by Environment Canada (2010) to maintain water quality by reducing nutrient, pollutant and sediment run-off and to maintain natural flooding cycles. It is supported by studies such as Castelle et al. (1994) and Champion (2009). Each of these studies indicates that site-specific conditions may dictate the need for a wider or narrower buffer depending on such things as topography, soil type, adjacent land uses.