Hill’s Thistle Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the Hill’s thistle, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

2013

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy.

The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. iii + 5 pp. + Appendix vii + 84 pp. Adoption of Recovery Strategy for the Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) in Canada (Parks Canada Agency 2011).

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

ISBN 978-1-4435-9437-0 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007, n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Cathy Darevic au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Hill’s Thistle was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Adoption of Recovery Strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) is listed as threatened on the SARO List. The species is also listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Parks Canada Agency prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Hill’s Thistle in Canada in 2011 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Species assessment and classification

Common name: Hill’s Thistle

Scientific name: Cirsium hillii

SARO List Classification: Threatened

SARO List History: Threatened (2005)

COSEWIC Assessment History: Threatened (2004)

SARA Schedule 1: Threatened (August 15, 2006)

Conservation status rankings:

- GRANK: G3

- NRANK: N3

- SRANK: S3

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Section 2.4 of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the areas of critical habitat identified in Section 2.4 be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

Appendix 1 - Recovery Strategy for the Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) in Canada

About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series

What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)?

SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.”

What is recovery?

In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species' persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured.

What is a recovery strategy?

A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage.

Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies – Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada – under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/approach/act/default_e.cfm [link inactive]) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Depending on the status of the species and when it was assessed, a recovery strategy has to be developed within one to two years after the species is added to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. Three to four years is allowed for those species that were automatically listed when SARA came into force.

What’s next?

In most cases, one or more action plans will be developed to define and guide implementation of the recovery strategy. Nevertheless, directions set in the recovery strategy are sufficient to begin involving communities, land users, and conservationists in recovery implementation. Cost-effective measures to prevent the reduction or loss of the species should not be postponed for lack of full scientific certainty.

The series

This series presents the recovery strategies prepared or adopted by the federal government under SARA. New documents will be added regularly as species get listed and as strategies are updated.

To learn more

To learn more about the Species at Risk Act and recovery initiatives, please consult the SAR Public Registry.

Recommended citation:

Parks Canada Agency. 2011. Recovery Strategy for Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) in Canada.

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Parks Canada Agency. Ottawa. vii + 84 pp.

Additional copies:

Additional copies can be downloaded from the SAR Public Registry.

Cover illustration: Hill’s Thistle at Lyal Island, by Jarmo Jalava

Également disponible en français sous le titre

« Programme de rétablissement du chardon de Hill (Cirsium hillii) au Canada »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2008. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-100-17325-2

Catalogue no: En3-4/87-2011E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Recommendation and approval statement

The Parks Canada Agency led the development of this federal recovery strategy, working together with other competent minister(s) for this species under the Species at Risk Act. The Chief Executive Officer, upon recommendation of the relevant Park Superintendent(s) and Field Unit Superintendent(s), hereby approves this document indicating that Species at Risk Act requirements related to recovery strategy development (sections 37-42) have been fulfilled in accordance with the Act.

Recommended by:

Frank Burrows

Superintendent, Bruce Peninsula National Park and Fathon Five National Marine Park, Parks Canada Agency

Approved by:

Kim St. Claire

Field Unit Superintendent, Georgian Bay, Parks Canada Agency

Approved by:

Alan Latourelle

Chief Executive Officer, Parks Canada Agency

All competent ministers have approved posting of this recovery strategy on the Species at Risk Public Registry.

Declaration

Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada. The Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA) requires that federal competent ministers prepare recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened species.

The Minister of the Environment presents this document as the recovery strategy for the Hill’s Thistle as required under SARA. It has been prepared in cooperation with the jurisdictions responsible for the species, as described in the Preface. The Minister invites other jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved in recovering the species to use this recovery strategy as advice to guide their actions.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best existing knowledge and are subject to modifications resulting from new findings and revised objectives.

This recovery strategy will be the basis for one or more action plans that will provide further details regarding measures to be taken to support protection and recovery of the species. Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the actions identified in this strategy.

In the spirit of the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, all Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the species and of Canadian society as a whole. The Minister of the Environment will report on progress within five years.

Acknowledgments

Parks Canada Agency led the development of the recovery strategy. The strategy was prepared by J.A. Jones for the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island Alvar

Strategic environmental assessment statement

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all Species at Risk Act recovery strategies, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals (2004). The purpose of a SEA is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally sound decision-making.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond their intended benefits. Environmental effects, including impacts to non-target species and the environment, were considered during recovery planning, and the results of this evaluation are discussed further in Appendix A: Effects on Other Species and the Environment.

The implementation of this recovery strategy is not expected to have any negative effects on the environment or on non-target species, and in fact is expected to benefit many other species found in the same habitat. However, researchers carrying out field studies, and those conducting monitoring in alvar habitat, need to be cautioned on the potential problem of trampling from their foot traffic, and instructed how to prevent creating such impacts. Whether controlled burning is required to maintain and improve habitat is an important knowledge gap. If burning is found tobe a necessary tool for recovery, then an additional SEA would need to be done on this action. This is addressed in Section 1.6 Knowledge Gaps.

Preface

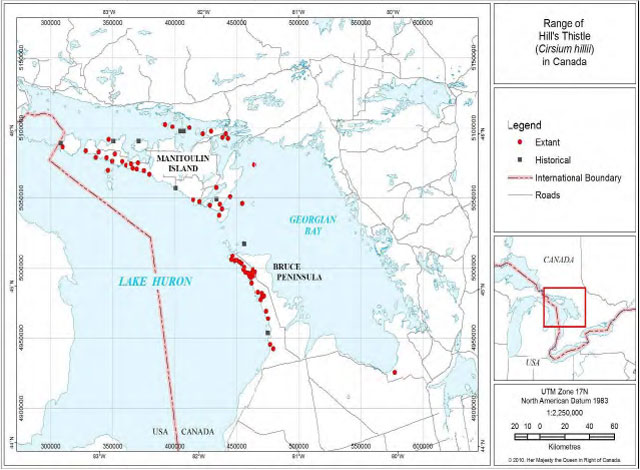

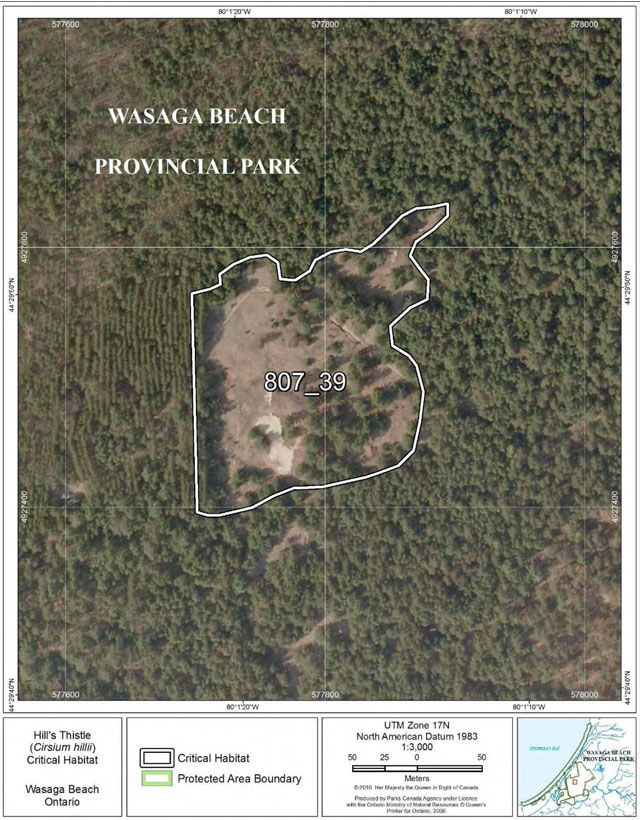

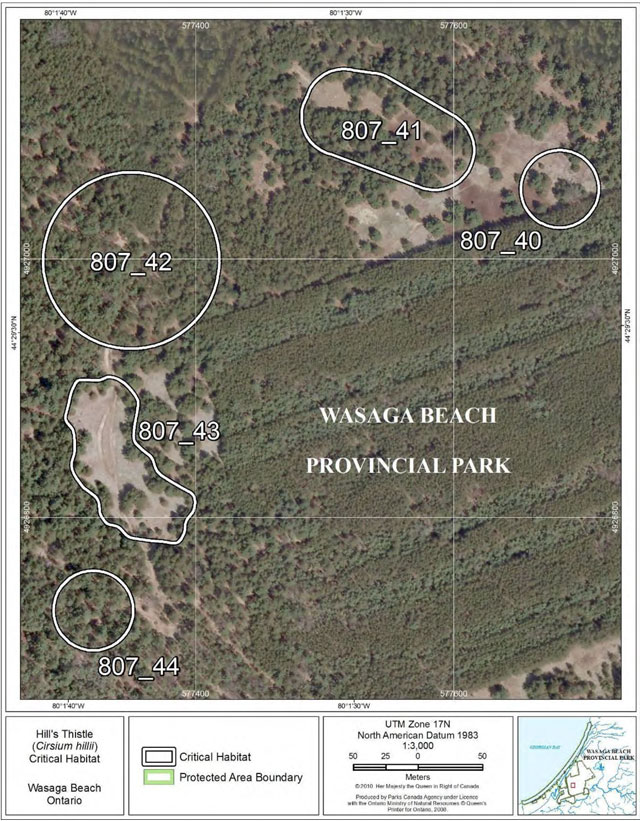

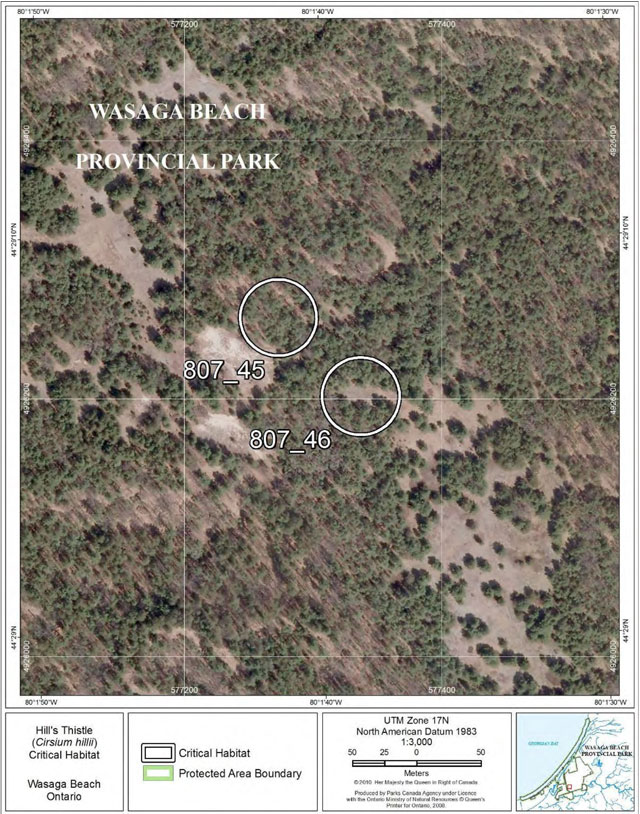

This Recovery Strategy addresses the recovery of Hill’s Thistle. In Canada, this species is found only in Ontario: on Manitoulin Island and surrounding islands, on the Bruce Peninsula, and at Wasaga Beach Provincial Park (Simcoe County).

The Parks Canada Agency, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, and the Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region, worked in cooperation to develop this recovery strategy, with the members of the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island Alvar Recovery Team, and in cooperation and consultation with stakeholders, and private landowners. All responsible jurisdictions reviewed and supported posting of the strategy. The proposed recovery strategy meets SARA requirements in terms of content and process (Sections 39-41) and fulfills commitments of all jurisdictions for recovery planning under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

Residence

SARA defines residence as: a dwelling-place, such as a den, nest or other similar area or place, that is occupied or habitually occupied by one or more individuals during all or part of their life cycles, including breeding, rearing, staging, wintering, feeding or hibernating [Subs. 2(1)]. The concept of residence under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) does not apply to this species. Residence descriptions, or the rationale for why the residence concept does not apply to a given species, are posted on the SARA registry: http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/plans/residence_e.cfm [link inactive].

Recovery feasibility summary

Recovery of Hill’s Thistle in Canada is considered feasible based on the criteria outlined by the Government of Canada (2009).

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

There are several natural, large, actively reproducing populations of Hill’s Thistle in locations with large areas of suitable habitat. This suggests that individuals are capable of reproducing at a rate sufficient to maintain and improve population sizes. - Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

One of the main threats to Hill’s Thistle is filling in of habitat, likely due to fire suppression. However, the most recent burning (at least for habitat in the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island regions) took place 100 or more years ago, so encroachment is a very slow process. In addition, although habitat patch sizes are shrinking, there are still a large number of sites. Therefore, there is enough habitat which can be restored or improved, and enough time to plan and implement management and restoration actions. Reinstating intense, catastrophic wildfire into the human landscape in order to recover Hill’s Thistle habitat would be a very difficult thing to do; however, other methods of maintaining existing habitat (e.g. low-level burning, cutting and clearing) may prove effective. This option still needs to be researched. - The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Many threats can be avoided or mitigated through communications actions to increase awareness about the species, liaising with other groups and agencies, erecting signage, working with management of protected areas, and many other steps. - Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

The Nature Conservancy’s International Alvar Initiative (IACI) (Reschke et al. 1999) initiated recovery of alvar ecosystems and associated rare species using several of the steps that are now suggested here for Hill’s Thistle, and experiences from the IACL show these techniques can be very effective.

Executive summary

Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) is listed as Threatened under Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). In Ontario, it is listed as Threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). The global rank of Hill’s Thistle is vulnerable, and is completely restricted to the Great Lakes Region. The Canadian range of Hill’s Thistle may account for as much as 50% or more of the global population.

Hill’s Thistle is a perennial with a deep tap root or a cluster of roots with tuberous swellings. The leaf margins and flower heads are spiny. The plants live as sterile rosettes for the first two to several years, until they produce an upright stem with a single, large flower head. After flowering and setting seed, the plants die. In Canada, Hill’s Thistle is only found in the Manitoulin Region, on the Bruce Peninsula, and at Wasaga Beach Provincial Park (Simcoe County). There are 93 known sites and upwards of 13,000 individuals.

This species requires dry, open, grassy ground with little canopy cover. The required habitat can be found within several different vegetation types including prairies, sand barrens, oak and jack pine savannas, alvars, openings in woodlands, and behind dunes.

Some habitat for Hill’s Thistle probably originates from fire, but there is little evidence to suggest that repeat burning after the initial fire at these sites has occurred. Hill’s Thistle often occurs in areas of historic-era disturbance; however, in Canada today Hill’s Thistle is never found in recently disturbed areas. In marginally suitable habitat, a trail may provide habitat where there is no other open ground, but in high quality habitat, anthropogenic disturbance may be detrimental and is not recommended as a management tool at this time. Threshold levels at which disturbance becomes harmful have not been determined.

Limited habitat is the primary threat to Hill’s Thistle. The limitation may be due to filling in of habitat due to fire suppression or loss of habitat from development (building and road construction). Other threats include heavy machinery use for ornamental stone removal and logging, trampling by pedestrians or mountain bikes, and indiscriminate use of all-terrain vehicles.

Recovery is considered feasible for Hill’s Thistle. The goal is to maintain, over the long-term, self-sustaining populations of Hill’s Thistle in its current range in Canada, by meeting population and distribution objectives targeted to recover the species to Special Concern or lower. The population and distribution objectives for Hill’s Thistle are:

- No continuing decline in total number of mature individuals, and

- Populations are maintained in the four core areas the species occupies.

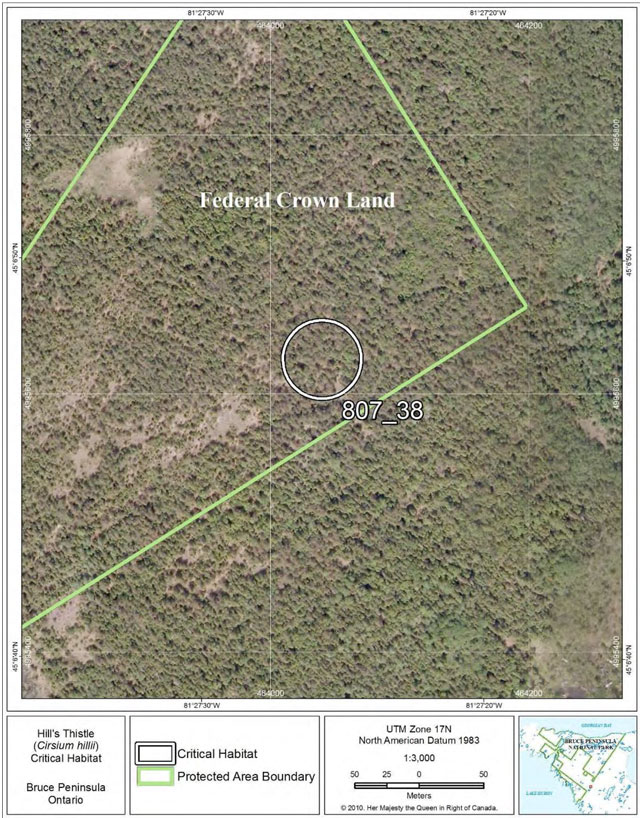

Critical habitat has been identified and mapped for 90 polygons at 17 sites on the Bruce Peninsula, at Wasaga Beach, and in the Manitoulin Region, and will contribute significantly to the recovery objectives. Other recovery tools will be used to meet the objectives, and these will be achieved through implementation of a suite of broad strategies and approaches.

One or more action plans will be developed by December 2015.

1. Background

1.1 Species assessment information from COSEWIC

Date of Assessment: November, 2004

Common Name: Hill’s Thistle

Scientific Name: Cirsium hillii (Canby) Fern.

COSEWIC Status: Threatened

Reason for Designation: This is a perennial herb restricted to the northern midwestern states and adjacent Great Lakes that is found in open habitats on shallow soils over limestone bedrock. In Ontario, it is found at 64 extant sites but in relatively low numbers of mature flowering plants that are estimated to consist of fewer than 500 individuals. Some populations are protected in national and provincial parks, however, the largest population is at risk from aggregate extraction. On-going risks are present from shoreline development, ATV use, and successional processes resulting from fire suppression within its habitat.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Threatened in November 2004. Assessment based on a new status report.

1.2 Species status information

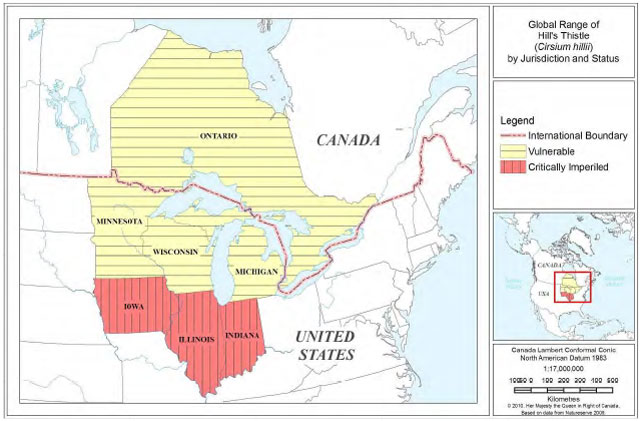

Hill’s Thistle is listed as Threatened and is on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). In Ontario it is listed as Threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). The global rank of Hill’s Thistle is G3 or Vulnerable (NatureServe 2009). The species is federally listed as a Species of Concern in the United States. It is currently listed as S1 or Critically Imperiled in Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa, and S3 or Vulnerable in Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota (NatureServe 2009). The range of Hill’s Thistle is completely restricted to the Great Lakes Region, and the Canadian range of Hill’s Thistle may account for 50% or more of the global population. See Section 2.1 Population and Distribution Context.

1.3 Description of the species and its needs

1.3.1 Species description

Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii (Canby) Fern.) is a perennial thistle with a single deep, hollow tap root or a cluster of roots with tuberous swellings. Spines are present along the undulating leaf margins and at the tips of the scales (involucral bracts) under the flower head. Hill’s Thistle plants live as sterile rosettes of leaves for several years (maximum five years) up until the final year when they produce an upright stem (25-60 cm) with a single, large flower head (3.5-5 cm in height) (NatureServe 2010). Flowering occurs from mid-June to mid-September with the main peak in July. Mature flowers are a rich mauve colour. Hill’s Thistle also reproduces vegetatively with buds along lateral roots (Higman and Penskar 1999). After flowering and setting seed, the plants and the primary tap root usually die, although new rosettes produced from adventitious buds may continue to grow. Unlike some weedy thistle species, Hill’s Thistle does not spread by rhizomes.

Hill’s Thistle can be distinguished from other thistles by the stem, which is sparsely hairy to wooly and lacking wings or spines. As well, the leaves of Hill’s Thistle are only shallowly lobed to wavy-margined and have fewer spines than those of other thistle species. The spines that are present on both the leaves and flower heads of Hill’s Thistle tend to be shorter and finer than those of other thistles (COSEWIC 2004; Higman and Penskar 1999).

In The Flora of North America (Kell 2006), Cirsium hillii is not considered a distinct species but is treated as Cirsium pumilum (Nuttall) Sprengel var. hillii (Canby) B. Boivin. According to NatureServe (2009), Cirsium hillii is apparently very similar in appearance to C. pumilum, but C. hillii differs in being a monocarpic perennial species (living a variable number of years as a rosette before flowering, setting seed, and dying) possessing shallowly-lobed stem leaves with short prickles, and a single hollow, tuberous root. C. pumilum, in contrast, is a biennial that possesses a solid tap root and deeply lobed stem leaves with numerous prickles.

1.3.2 Species needs

Biology

Little information exists in the literature on the biology of Hill’s Thistle other than what is already presented in the species description above. Additional background on Hill’s Thistle compared to other thistles can be found in Moore and Frankton (1974).

Habitat and associates

Hill’s Thistle requires habitat that is dry and open with little canopy cover (Figure 1a). The species is typically found in patches of open ground growing with low grasses, especially Poverty Oat Grass (Danthonia spicata), reindeer lichens (Cladina rangiferina and C. mitis), and scattered shrubs (Figure 1b). It is not found in dense vegetation or in situations where it is overtopped or crowded by other plants (Jones 1995-2008; COSEWIC 2004; Jalava 2004-2008; Janke et al. 2006; White 2007a). The tree canopy, if present, is predominantly coniferous and very open in a savanna or woodland situation.

The open and grassy habitat required by Hill’s Thistle can be part of several different vegetation types, including prairies, sand barrens, oak and jack pine savannas, some types of alvars, in open woodlands, and at the backs of dunes (both current and relict) (Voss 1996; Penskar 2001; NatureServe 2009). Hill’s Thistle has been considered by many to be an alvar species (Catling 1995; Brownell and Riley 2000); however it can occur in other vegetation types, provided the correct conditions are present. Many different vegetation community types that support Hill’s Thistle have been documented.

Typical associates are native graminoids such as Poverty Oat Grass, Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Ebony Sedge (Carex eburnea), and Richardson’s Sedge (Carex richardsonii), as well as reindeer lichens, Common Juniper, Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), Creeping Juniper, and Dwarf Lake Iris (Iris lacustris) (COSEWIC 2004; Jalava 2004-2008; Jones 1995-2008).

Soils

Soils range from sandy near the Lake Huron shore to silty and slightly alkaline on alvars. Soils are often shallow or may consist of no more than a mound of sand on top of flat limestone or dolostone bedrock.

The role of fire

Fire is probably required to create or maintain the habitat of Hill’s Thistle. Many vegetation types in which the species occurs are considered “fire-prone” or “fire-dependent” (COSEWIC 2004; Penskar 2001; Higman & Penskar 1999) since fire prevents the accumulation of shrubs and trees. However, it is probably more accurate to say these vegetation types were created by fire. Jones (2000) showed that nearly all oak savannas in one region of Manitoulin Island were deciduous forests prior to a historic fire and were created in a single event, but almost none had burned a second time. A large number of alvars on the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island were burned in the past, but most of the burn evidence appears to be very old with no recent burning (in the last 50-70 years). In addition, a great deal of Manitoulin Island was burned prior to the first land surveys in the 1870s, but there have been very few fires since then (Jones and Reschke 2005; Jones 2000; Reschke et al. 1999). Finally, suitable habitat still exists now, more than 100-150 years after most major fires occurred in the habitat, so fire may be needed only on long cycles of time, perhaps every 100-200 years or more.

There is little evidence that frequent, low-level fire maintained the habitat historically. However, given the need for fire suppression to protect human life and property, it is possible that low- level controlled burning may be required to maintain habitat in the absence of canopy-reducing fires. The results of a controlled burn at Wasaga Beach Provincial Park in 2004 are inconclusive as to whether there was a benefit to Hill’s Thistle (White 2007a; Korol pers. comm. 2007). Insights may be gained through ongoing monitoring at this site. As well, Jones (unpublished field notes 2007) observed five locations on Manitoulin Island that had undergone burning in the last five to 30 years near to extant Hill’s Thistle populations. None of these burns resulted in the creation of vegetation similar to that in which Hill’s Thistle is currently found.

Disturbance

Hill’s Thistle often occurs in areas of very old disturbance such as sites of old burning or historic-era logging. Hill (1910) observed the species in 1910 south and west of Chicago “in railway enclosures fenced off from the surrounding prairie before the land has been touched by the plow”. He also noted that the species was able to spread into pastures and fallow agricultural fields. Nonetheless, these areas were likely not as disturbed, nor as weedy, as they are today and they probably still contained a significant component of native flora. Today in Canada, Hill’s Thistle is never found in heavily disturbed areas or in fallow agricultural fields (Jones pers. obs.; Jalava pers. obs.; habitat data on file in NHIC database, NHIC 2009).

Figure 1-A. Typical Hill’s Thistle habitat with open grassy ground.

Figure 1-B. Basal rosettes of Hill’s Thistle (centre) with its typical associates of Poverty Oat Grass (throughout background) and Bearberry (small, round shiny leaves, at centre top and bottom right).

Whether or not Hill’s Thistle requires disturbance may depend on the quality of the existing habitat. For habitat that is becoming densely vegetated, it has been suggested that light disturbances, such as lightly used trails, may help keep small patches of ground open, thus creating or maintaining habitat for Hill’s Thistle (COSEWIC 2004). Indeed, there are several observations of Hill’s Thistle growing along trails (TNC 1990 cited in COSEWIC 2004; Jones 1995; Jalava pers. comm. 2009). In some cases where the vegetation is closing in, the trail is the only open ground remaining.

On the other hand, in large areas of good quality, open, grassy habitat, even light anthropogenic disturbance (such as occasional ATV use on a designated trail) can cause considerable damage, by bringing in weeds, creating ruts, disrupting soil, thus causing a general degradation of habitat (Jones unpublished field notes 2007). Therefore, while light disturbance may be useful in marginal habitat, in good quality habitat it may be detrimental. Furthermore, such anthropogenic disturbance would be very difficult to control and is not recommended as a tool to maintain habitat. Threshold levels at which disturbance becomes harmful have not been determined. Further study of techniques and processes to keep habitat open is recommended (see Knowledge Gaps, Table 2).

1.4 Threat identification

Loss of suitable habitat from filling in of habitat due to fire suppression or from development are the primary threats to Hill’s Thistle. These and other threats are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Current threats affecting Hill’s Thistle by core area. Intensity of threats is: high (H), medium (M), low (L), or nil (N/A).

| Threat | Manitoulin & Lake Huron Islands | North Channel & Georgian Bay Islands | Bruce Peninsula | Wasaga Beach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited Habitat | High | High | High | High |

| Development | High | Low | High | N/A |

| Heavy Machinery | Medium | High | Medium | N/A |

| Trampling | Low | Low | Medium | Medium |

| All-terrain Vehicles | Medium | Low | Medium | Low |

1.4.1 Description of threats

-

Limited habitat

Lack of suitable habitat has been identified as the primary threat to Hill’s Thistle (Jones 1995-2008; COSEWIC 2004). The species is very restricted in its requirements for natural, dry, open, grassy patches. Suitable habitat was formerly much more widespread after extensive historic fires on Manitoulin Island and the Bruce Peninsula (Jones and Reschke 2005). Now, after more than 100 years of human suppression of the natural fire regime, filling-in of the vegetation has resulted in small isolated habitat patches, unsuitably low light levels, and higher competition for ground space and nutrients. Lack of wild fire also allows leaf litter to build up on the ground, which results in poor seedling establishment (Higman and Penskar 1999). Although habitat may close in at a very slow rate, much of the remaining extant habitat is now at the point of becoming unsuitable due to the density of vegetation and the habitat patch size (<1/2 ha).

-

Development: building and road construction

Most Hill’s Thistle occurrences are near the Lake Huron and Georgian Bay shoreline in areas which are prime real estate for development. Even away from the shorelines, for example in the centre of Manitoulin Island, open grassy areas are frequently chosen as places to build cottages, hunt camps, and other structures because the open ground does not need to be cleared. Building and road construction destroy both habitat and individual plants.

-

Heavy Machinery for Ornamental Stone Removal and Logging

Driving heavy machinery in Hill’s Thistle habitat destroys individual plants and compacts or displaces shallow soils leaving huge ruts. It also introduces weed species, which may reduce or eliminate the native species. Heavy machinery is used to remove erratic glacial boulders (which have economic value to the landscaping industry) from the habitat. Machinery for logging operations in forests adjacent to alvars frequently ends up crossing open habitat or being parked there. In addition, log landing areas are frequently located in open habitats adjacent to forests.

-

Trampling by Pedestrians or Mountain Bikes

Several populations in protected areas are located on hiking trails and can threatened by trampling, which can destroy the plants, displace soil, and bring in weeds. However, there are many situations where Hill’s Thistle grows on trails that are maintained in a suitable state by a low level of human usage. This is especially true when the trail provides the only remaining suitably open ground. Therefore, managing intensity of usage to achieve the correct balance is needed, and detecting the point where usage becomes impactful is a key issue.

-

All-Terrain Vehicles (ATVs)

As with trampling, ATV use is a threat to Hill’s Thistle when it occurs in sufficient intensity to damage or destroy plants, displace soil, cause ruts, or introduce weed species that reduce native species presence. Moreover, unlike larger vehicles, ATVs are not limited to trails, so the damage is often much more widespread. All-terrain vehicle use has probably caused the extirpation of at least one Hill’s Thistle population (COSEWIC 2004). However, there are situations where Hill’s Thistle is found along the edges of ATV trails because the trail is the only remaining open ground in an encroaching forest (Jalava pers. com. 2009; and field data on file in NHIC database). Whether a low level of ATV use may maintain habitat or damage it may also depend on the location or vegetation type. Dunes and alvar grasslands are particularly vulnerable to damage, and therefore may not withstand even light ATV use. Again, monitoring the level of usage is essential. See the discussion on disturbance in Section 1.3.2 for further explanation.

Other potential threats

-

Aggregate Extraction

The Bruce Peninsula is a prime location for the quarrying of limestone, and alvar habitats where there is little cover of bedrock are preferred sites for this type of development. Hill’s Thistle plants located during the environmental work for the approvals process must be protected, but development of new quarries can cause loss of habitat. In the Manitoulin Region, Hill’s Thistle occurs within two already-licenced quarries (International Alvar Conservation Initiative field notes 1996; COSEWIC 2002), but the current status of these populations is unknown. Development of new aggregates sites in the Manitoulin Region now requires a natural environment technical study as the region has been designated under the provincial Aggregates Act. Thus, Hill’s Thistle plants should now receive more protection in that region.

-

Browsing or Damage by White-tailed Deer

On Manitoulin Island, stems of Hill’s Thistles with the flower heads eaten off have been observed (Jones 1996-2009 unpublished observations). For small populations of Hill’s Thistle where only a few individuals may flower, sometimes after a period of many years, loss of flower heads to browsing may be a serious threat. Deer are abundant in the Manitoulin Region and damage to vegetation is frequently observed (Selinger pers. comm. 2010).

1.4.2 Limiting factors

Low seed viability and low seed germination rates may be limiting factors for this species, and seedlings may be poor competitors for light and space (NatureServe 2010). However, the primary problems affecting Hill’s Thistle are threats, not intrinsic limitations (Jones 2004-2009; Jalava 2004a, 2005, 2007, 2008a, b).

1.5 Actions already completed or underway

In order to plan recovery of Hill’s Thistle, it is important to see the work that has already been done to avoid duplication of efforts. Much work to protect alvars and increase awareness of their significance pre-dated this recovery strategy. Many of these actions have directly protected or otherwise benefited Hills Thistle populations. Some of the major accomplishments include:

The International Alvar Conservation Initiative (IACI)

This bi-national, range-wide study of alvars produced detailed, standardized field inventories of the majority of significant alvar sites in Ontario, Michigan, New York, and Ohio (Reschke et al. 1999). Fieldwork included botanical surveys, vegetation community inventory, classification and mapping, and specific studies on a number of ecological processes including fire history and natural succession (Schaefer 1996, Schaefer and Larson 1997, Jones 2000, Jones and Reschke 2005). Information on Hill’s Thistle was collected at many major sites as part of this survey. As well, several major alvar sites that support Hill’s Thistle (including Quarry Bay, Belanger Bay, and Burnt Island Harbour) were protected as a result of this project. Stewardship packages were distributed to alvar landowners to raise awareness of the uniqueness of the alvar ecosystem and its rare species (including Hill’s Thistle) (Jalava 1998; Jones 1998).

The Ontario Alvar Theme Study

This ecological study of Ontario alvars ranked significant alvars on a regional basis (Brownell and Riley 2000). Presence of Hill’s Thistle was one of the special features upon which the ranking was based.

Wasaga Beach Provincial Park

This park has had a monitoring program for Hill’s Thistle in place since 1996 (White 2007a, b) and conducted a controlled burn in its habitat in 2004 (Jackson 2004). The results of these efforts will be useful as background information for the design of range-wide monitoring and habitat management plans for Hill’s Thistle.

Protected areas

A number of alvars have been protected in the last 10 years as a result of conservation work for that ecosystem (Parks Canada Agency 2010). Many of these alvar sites support populations of Hill’s Thistle. See Section 2.7 Habitat Conservation, for a list of the protected areas which support Hill’s Thistle.

Protected Areas Management

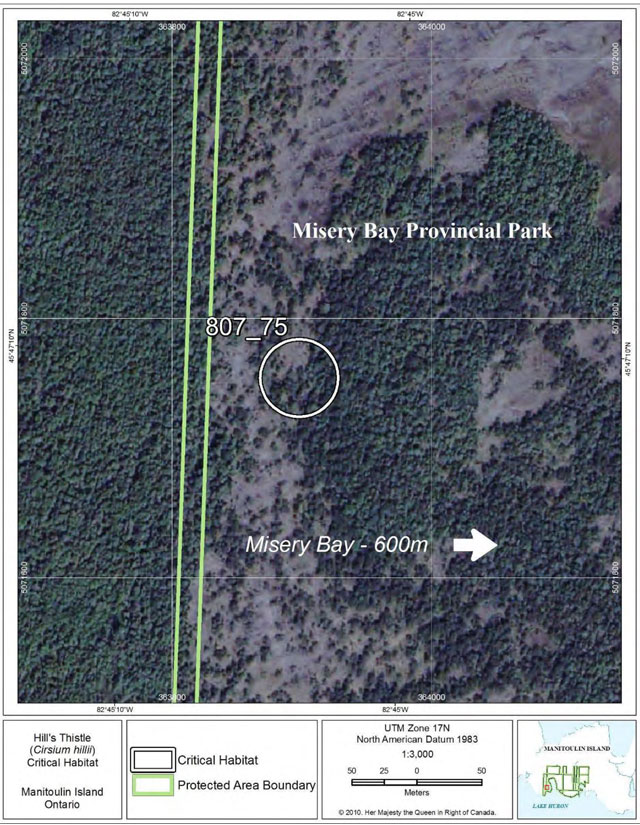

At Bruce Peninsula National Park (BPNP), Misery Bay Provincial Nature Reserve, Queen Elizabeth-Queen Mother M'nidoo M'nissing Provincial Park, and private nature reserves such as the Quarry Bay Nature Reserve, management is focusing on maintaining ecological integrity of habitats, including many areas where Hill’s Thistle is present.

1.6 Knowledge gaps

Table 2 summarizes important knowledge gaps for Hill’s Thistle in Ontario. Filling these gaps will provide information that can be used to reduce threats or to better manage habitat. As well, a better understanding of species biology may clarify which threats are serious impacts and which are not.

Table 2. Summary of knowledge gaps.

| Need to know: | In order to show: |

|---|---|

| How controlled burning affects Hill’s Thistle | Whether fire can be used to maintain habitat |

| The period in which habitat becomes unsuitable due to natural succession, versus the long-term cycle by which new habitat is created | Whether periodic fire historically maintained habitat and whether fire is important in naturally functioning habitat |

| Threshold tolerance levels for disturbance | Levels at which some activities may or should continue in critical habitat |

| Whether cutting back tree canopy and clearing surrounding shrubs would improve habitat | Whether this method can maintain suitable habitat in the absence of fire |

| Whether the presence of weedy species affects habitat suitability and accessibility for Hill’s Thistle | Whether the presence of exotic species contributes to a decline in Hill’s Thistle |

| Whether Hill’s Thistle is self-fertile | Level of threat caused by geographic isolation |

| Whether there is less flowering in small populations | Whether small population size is a threat; Whether isolation of small populations creates greater risk |

| The amount of genetic diversity in regional meta-populations | Level of threat due to isolation of habitat patches in a landscape that is closing in; Level of threat from genetic isolation |

| The length of time seeds are viable | The length of time populations can survive with no flowering individuals; Length of time populations can survive waiting for creation of new habitat |

| About seed dispersal mechanisms | How Hill’s Thistle moves within and between habitat patches; What patch size is needed for survival and/or recovery; |

| Ecological role of Hill’s Thistle seeds as a food source for animals and insects | Whether seed predation limits reproductive capacity |

2. Recovery

2.1 Population and distribution context

NatureServe (2009) reports 141 sites globally, and COSEWIC (2004) listed 64 sites

Figure 2. Global Range of Hill’s Thistle by Jurisdiction. Red areas: - Critically Imperiled; Yellow areas: Vulnerable (NatureServe 2009).

The Canadian range is restricted to Ontario (Figure 3); populations are located in Simcoe County (1 site), Bruce County (29 sites) and the Manitoulin District (63 sites, of which 20 are on islands other than Manitoulin Island). A complete list of all Canadian Hill’s Thistle sites is provided in Appendix B, and a list of sites where Hill’s Thistle is considered extirpated is given in Appendix C.

Figure 3. Range of Hill’s Thistle in Canada (Environment Canada 2009).

The total number of plants in Canada is estimated to be in excess of 13,000 individuals (Jones 2004-2009; Jalava 2004a, 2005, 2007, 2008a, b; data on file in NHIC database). Several exceptionally large populations and areas of habitat exist (Appendix B), and recently, three populations have been documented that contain >1,000 individuals: Wikwemikong First Nation and Taskerville on Manitoulin Island, and Saugeen First Nation, on the Bruce Peninsula. The size of the Wikwemikong and Saugeen populations were not known at the time of the 2004 COSEWIC report. In addition, four populations are documented as containing >500 individuals.

There are essentially no data showing trends in population size because no long-term monitoring has been done other than at Wasaga Beach Provincial Park. The population there has been stable since 2001; however, it has declined significantly over the entire monitoring period of 1996-2007 (Burke Korol pers. comm. 2007).

The Canadian population as a whole is probably decreasing due to habitat loss from succession (closing-in of forest openings and grasslands), as well as from anthropogenic threats. Loss of habitat is certainly observable. COSEWIC (2004) reports the total area of occupied habitat at 30 km2 (Index of Area of Occupancy

The natural, open grassy areas in which Hill’s Thistle is found such as prairies, oak savannas, and alvars, are all vegetation communities deemed to be in decline (ranked “Vulnerable” or less by NHIC 2008). The species can also be found in grassy forest openings, which may be remnants of former larger open habitats.

2.2 Population and distribution objectives

The goal of this recovery strategy is to maintain over the long-term, self-sustaining populations of Hill’s Thistle in its current range in Canada. Specifically, recovery for Hill’s Thistle in Canada is interpreted as a change in the species status from its current Threatened designation to Special Concern, or lower, as assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Based on the information presented above, the population and distribution objectives for Hill’s Thistle until 2020 are:

- No continuing decline in total number of mature individuals.

- Populations are maintained in the four core areas the species occupies (Bruce Peninsula; Wasaga Beach, Manitoulin Island, and islands surrounding Manitoulin).

Rationale:

In the 2004 COSEWIC assessment, Hill’s Thistle was designated as Threatened because of its “Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals” and its “Very Small Population”. In the first category, the species met the Endangered criteria of <2500 mature individuals, a continuing decline in numbers of mature individuals, and no population totaling >250 flowering plants. In the second category the species met the Threatened criteria of <1,000 mature plants. Hill’s Thistle was designated Threatened rather than Endangered because imminent extirpation was unlikely given the occurrence of numerous sites, the presence of about one third of the populations in protected areas, few recent losses, and the fact that not all sites had been completely surveyed (COSEWIC 2004).

As noted in the Population and Distribution Context section, 29 additional populations have been discovered since the 2004 COSEWIC status report (a 45% increase), and the sizes of Hill’s Thistle populations have been better documented. The total number of mature individuals was estimated in 2004 to be about 500 flowering plants. Recently, three populations have been documented that contain >1,000 individuals, and another four are >500 individuals. The total Canadian population is now estimated to contain more than 13,000 individuals. The proportion of the total number of plants that are mature in any single year remains largely unknown for the species in Canada, and may vary among populations. However, it is prudent to assume that the current number is close to the threshold of 1,000 mature plants.

Therefore, the expectation under the objectives stated above is that in future evaluations Hill’s Thistle could remain in the “Very Small or Restricted Total Population”, but would no longer be considered under the “Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals”. COSEWIC uses the term “continuing decline” to mean “a recent, current or projected future decline (which may be smooth, irregular or sporadic), that is liable to continue unless remedial measures are taken.” Although it is expected that there will be some “naturally occurring” extirpation of very small populations (e.g. <10 individuals), mostly as a result of habitat becoming unsuitable through the filling in of vegetation, these isolated losses could well be offset over the long term by the growth and expansion of some of the larger populations, especially those in protected areas.

Another key criteria that Hill’s Thistle must meet to no longer qualify as Threatened is that the Index of Area of Occupancy be >20km2. The IAO captured by the critical habitat as mapped in the recovery strategy is 56 km2 (39% of the total 145 km2) and the Extent of Occurrence

Maintenance of Hill’s Thistle in the four core areas will prevent major contraction of the species' distribution range and potentially preserve the species' genetic diversity and local adaptations.

2.3 Broad Strategies and Approaches to Recovery

Recovery of Hill’s Thistle will largely be addressed through ecosystem-based actions for the recovery of alvars or other open habitats, as well as through actions specifically to benefit the species. Broad approaches will primarily be protection and maintenance of existing populations, reduction of threats to habitat, promoting site stewardship through outreach and public education, and using monitoring information and research to guide recovery actions.

Hill’s Thistle is one of many species-at-risk (SAR) found in the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island region. It is crucial that recovery of Hill’s Thistle be coordinated with recovery activities being undertaken for other SAR in the same region. This will be the best use of resources and personnel and will be very important in keeping the public engaged and preventing confusion among species. Recovery efforts for Hill’s Thistle in the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island region will be done in coordination with the Pitcher’s Thistle - Dune Grasslands Recovery Team, which is also working in the Manitoulin Island - Lake Huron region. There is some overlap in membership between the two teams, as well as in agency staff that are handling both recovery efforts. Also, a great number of Hill’s Thistle populations are found on First Nations lands. These communities should be engaged in action planning for the species.

2.3.1 Protection and maintenance of existing populations

Evaluation of site-appropriate conservation tools is a required approach because Hill’s Thistle occurs in many different types of ownership and jurisdiction, so a variety of different protection measures are needed. Recovery in protected areas will be based on management actions such as controlling recreational use (or other threats) to prevent impacts to Hill’s Thistle and its habitat, constructing barriers to control access, and establishing appropriate zoning for areas where the species is present. Outside protected areas, some examples of site-appropriate conservation tools may include tax incentive programs, conservation easements, funding for habitat protection such as fencing, etc. Acquisition by conservation partners of high priority sites, if they become available, may also be an approach. Encouraging and enforcing compliance is also a necessary approach, where other management measures fail to protect Hill’s Thistle.

2.3.2 Reduction of threats to habitat

Threats reduction will largely be done through protection of existing populations and promoting good stewardship. The actual approaches used to address threats will depend on the threats present at individual sites. Some approaches may include working with land managers on site- appropriate activities such as posting signage and constructing barriers to reduce damage by pedestrians and vehicles, and working with municipalities to ensure Hill’s Thistle and its habitat are considered during new development. Enforcement may also be required at some sites.

Addressing the threat of habitat loss from filling in of vegetation may be complex. An important approach is to determine whether controlled burning is a useful tool to reduce this threat. Hand removal of shrub material to open up ground is also a potential tool that needs testing.

2.3.3 Promoting site stewardship

Recovery on municipal lands will require coordinating and sharing habitat information with planning agencies, facilitating discussion of legal and policy approaches, and helping with site- appropriate management planning. Working with the aggregates industry on protection and restoration of alvars during and after extraction will also be an approach. On private and First Nations lands, actions will require working cooperatively with owners and communities on best management practices.

Communications to engage the public in valuing and protecting Hill’s Thistle and open habitat is vital. A key to encouraging good stewardship is helping landowners and managers understand what they have on their lands. As well, many populations are on municipal shorelines that have a public right-of-way through them, so educating the public about conscientious use will also be an approach. For populations occurring on First Nations lands, communications and outreach will be needed to gain assistance from the community in protecting Hill’s Thistle and its habitat. Cooperating with local partners, such as local stewardship councils, fish and game clubs, etc., to promote awareness and protection of publicly accessible habitat, will also be necessary.

2.3.4 Using monitoring information and research to guide recovery activities

Monitoring information will be essential to recovery because the information gathered will show where recovery efforts are needed most. Monitoring can show if urgent threats need to be addressed, or if protection measures are working. Examples might be tracking visitor foot traffic on trails with Hill’s Thistle, or checking for deer browse to see if it is a problem. Monitoring abundance and population trends will also be used to track recovery. Research is one of the primary approaches to recovery of Hill’s Thistle, and Section 1.6 Knowledge Gaps, addresses the current important research questions.

Timelines and benchmarks for these strategies are given in Section 2.6 Measuring Progress.

2.4 Critical habitat

Critical habitat is defined in Section 2(1) of the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c. 29) as “the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed species and that is identified as the species' critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species”. In a recovery strategy, critical habitat is identified to the extent possible, using the best available information. Ultimately, sufficient critical habitat will be identified to completely support the population and distribution objectives.

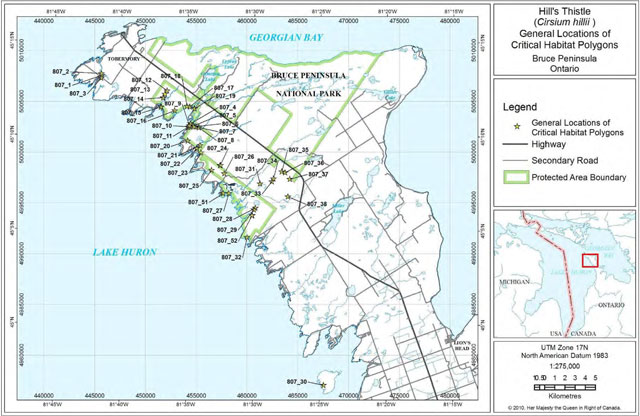

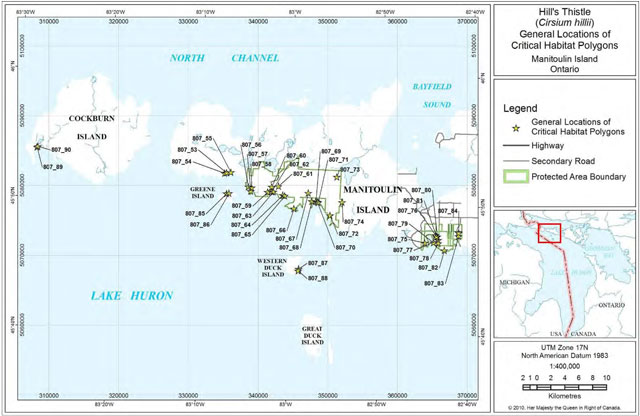

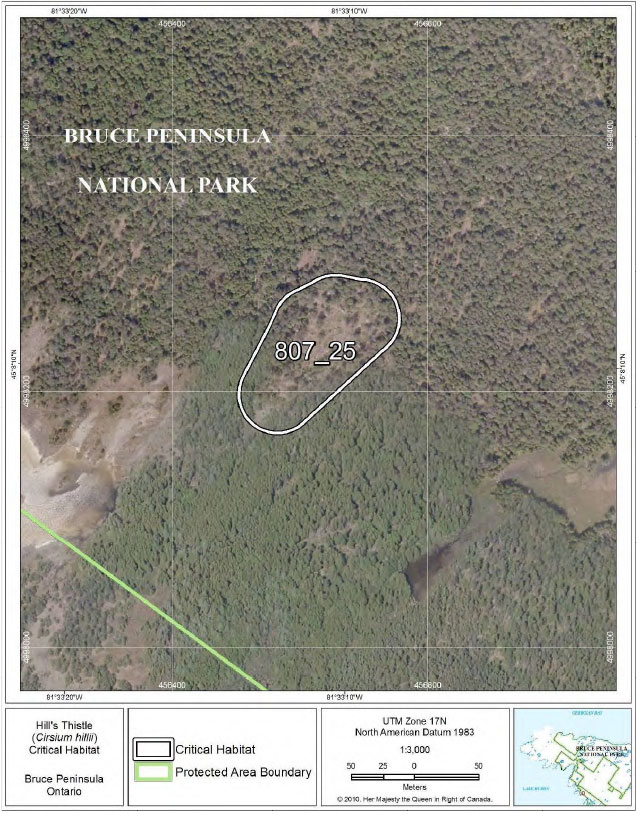

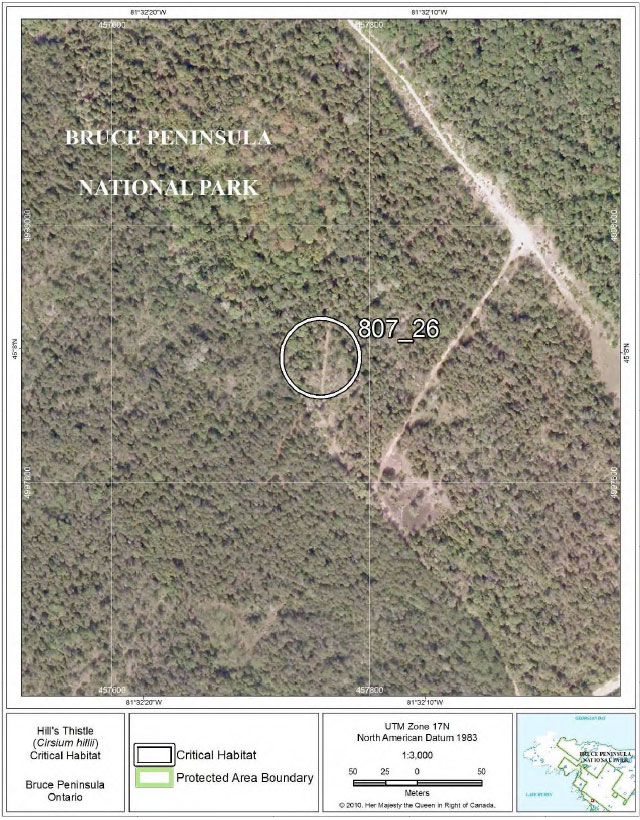

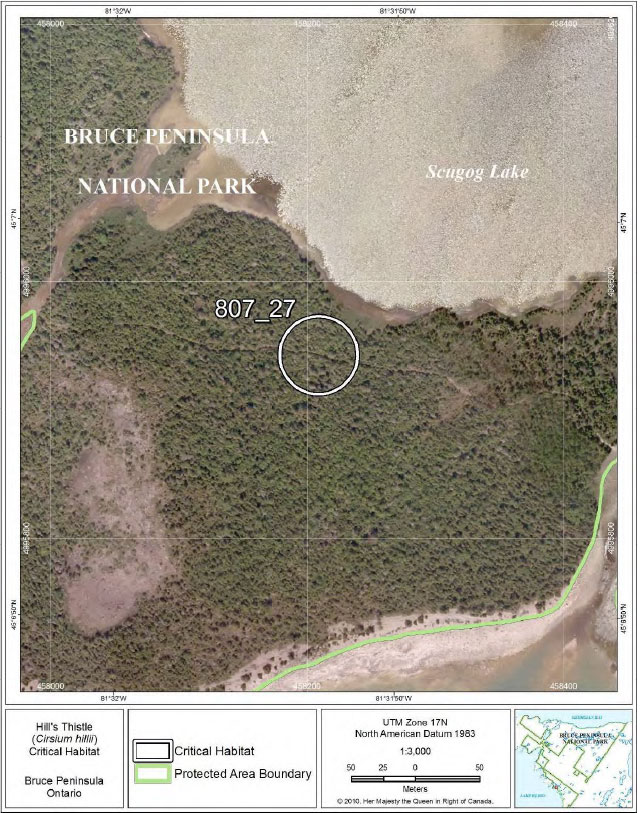

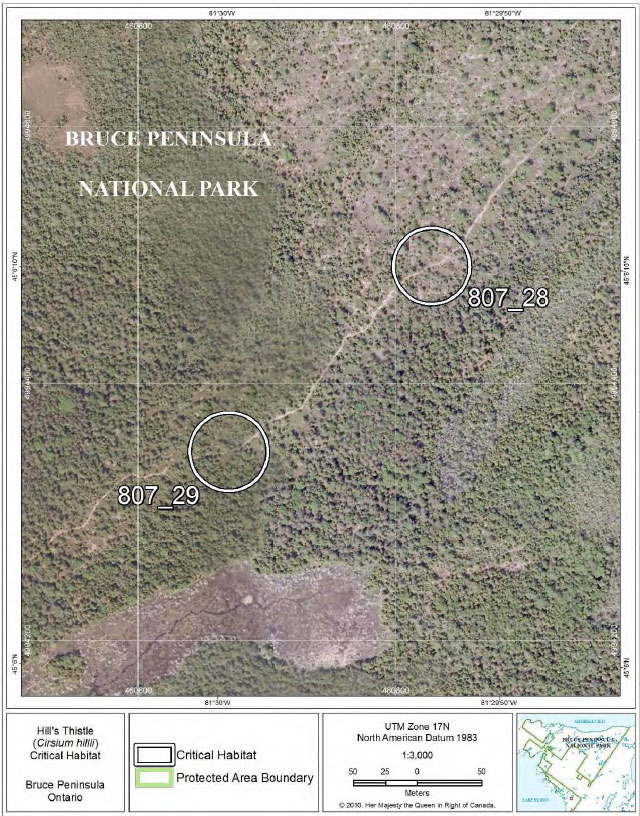

Critical habitat has been identified for Hill’s Thistle and the amount of critical habitat identified in this recovery strategy contributes to a substantial portion of the targets outlined in objectives 1 and 2 (Section 2.2), but does not fully meet the objectives. In total, 90 critical habitat polygons are identified at 17 sites in the Manitoulin Region (38), the Bruce Peninsula (40), and Wasaga Beach Provincial Park (12). This mapped critical habitat captures an IAO of 56 km2, and an Extent of Occurrence of 9,150 km2. Per objective 2, critical habitat is also mapped in each of the four core areas the species occupies. Recent surveys funded by the Species at Risk Program have discovered many additional populations of Hill’s Thistle. At this time, we do not have adequate information to determine which of those populations should be identified as critical habitat to achieve the objectives. A schedule of studies, which outlines the work required to complete the identification of critical habitat, is included below. In the meantime, implementation of the broad strategies and approaches, as outlined in Section 2.3, will aid in meeting the population and distribution objectives.

2.4.1 Information used to identify critical habitat

Critical habitat was identified from current data on habitat occupied by the species. Confirmed records on the Bruce Peninsula, at Wasaga Beach, and in provincial parks, crown lands

Habitat for Hill’s Thistle occurs as patches within several types of open non-forested vegetation, or as openings within successional forest (based on field work by many workers including Reschke et al. 1999; Brownell and Riley 2000; Jalava 2004-2008; Jones 2004-2008; North-South Environmental 2005; vegetation community data from the aforementioned workers is on file at NHIC). In Canada, critical habitat is found within the following vegetation community types, as per the Ecological Land Classification of Ontario (ELC) (Lee et al. 1998):

Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island Region

- ALO1-3 Dry-Fresh Little Bluestem Open Alvar Meadow

- ALO1-4 Dry-Fresh Poverty Grass Open Alvar Meadow

- ALS1-1 Common Juniper Shrub Alvar

- ALS1-2 Creeping Juniper-Shrubby Cinquefoil Dwarf Shrub Alvar

- ALS1-3 Scrub Conifer-Dwarf Lake Iris Shrub Alvar

- ALT1-3 White Cedar-Jack Pine Treed Alvar

- ALT1-4 Jack Pine-White Cedar-White Spruce Treed Alvar

Wasaga Beach

- TPW1 Dry Black (Red) Oak-White Pine Tallgrass Woodland

- TPO1-1 Dry Tallgrass Prairie-Open Sand Barren

- FOC1-2 Dry-Fresh White Pine-Red Pine Coniferous Forest

- FOM2-1 Dry-Fresh White Pine-Red Oak Mixed Forest Cultural Meadow/Dry Tallgrass Prairie

These community types often have a distinct boundary where they change from open (suitable) to forest, wetland, or cultural meadow (all unsuitable). Thus, the general areas in which critical habitat patches occur are fairly easy to distinguish in the field and relatively easy to map (methodology below). All known alvar sites on the Bruce Peninsula and at Wasaga Beach have recently been mapped in detail based on a compilation of more than 15 years of field data and observations of satellite imagery (North-South Environmental Inc. 2005; Jalava 2008a).

2.4.2 Critical habitat identification

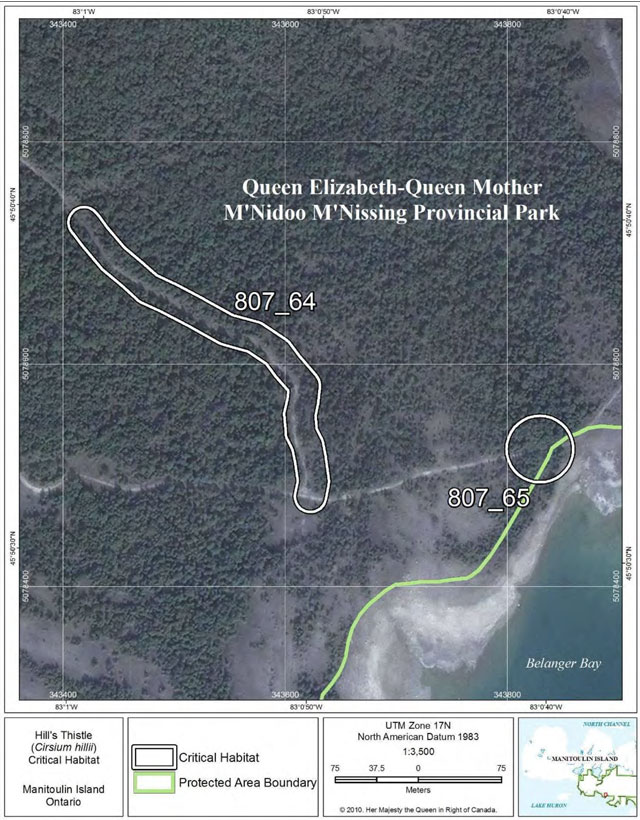

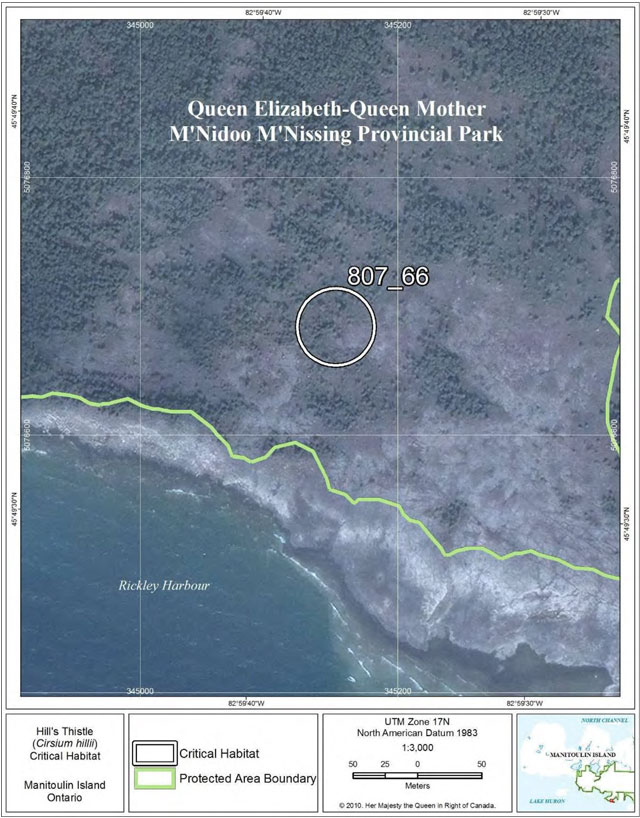

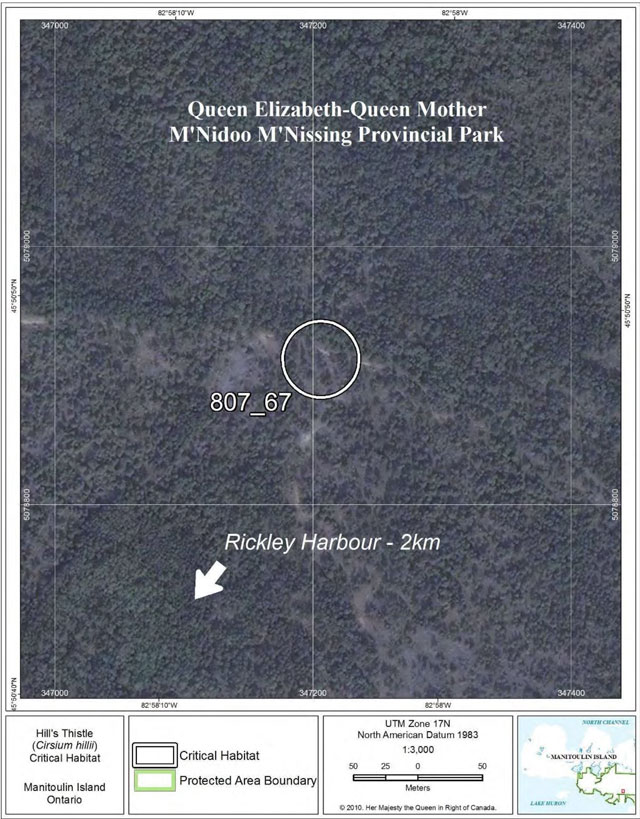

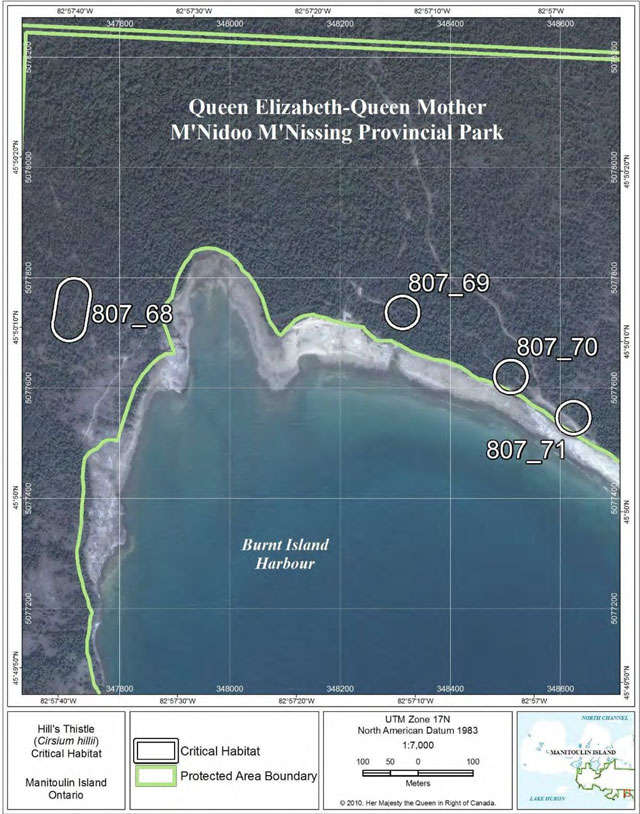

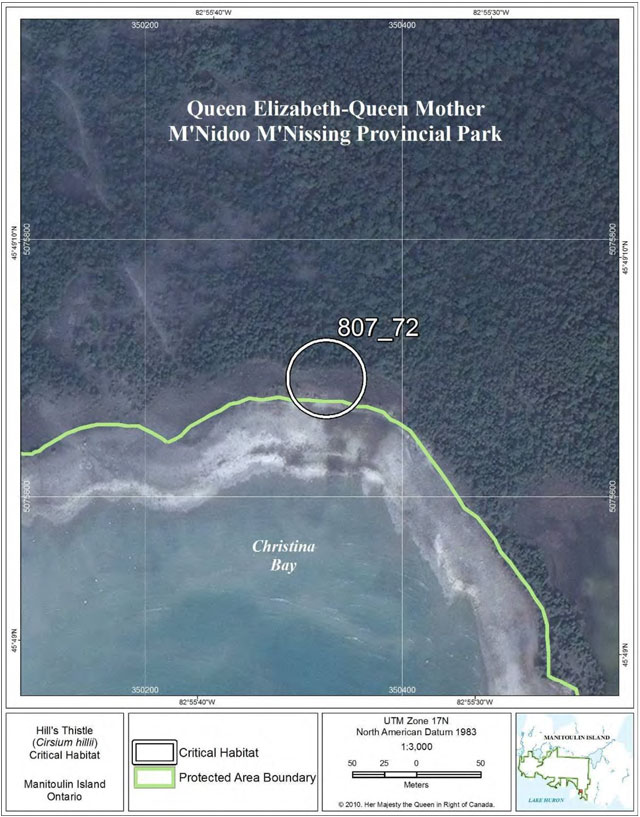

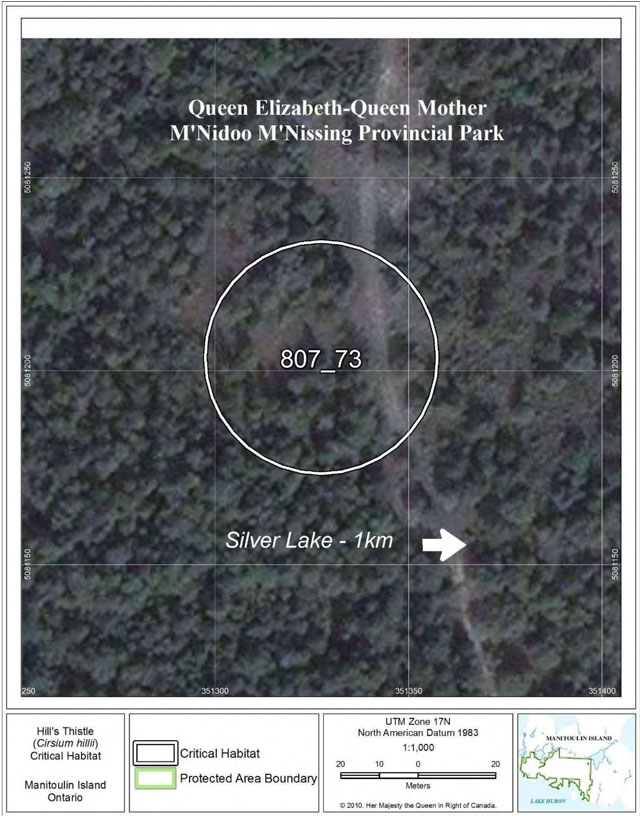

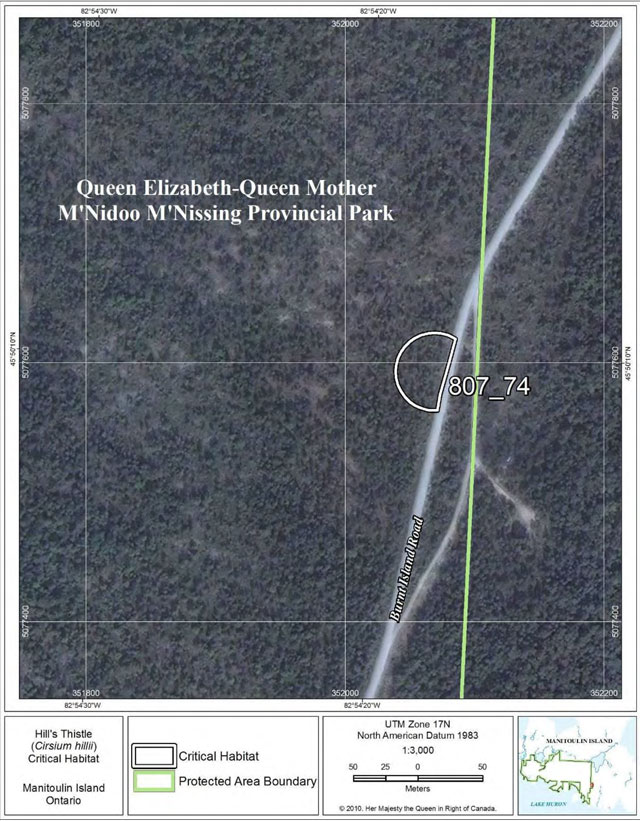

Critical habitat for the Bruce Peninsula and Wasaga Beach Provincial Park was mapped by Parks Canada in October 2009, and for the Manitoulin Region by Parks Canada in cooperation with staff from Ontario Parks, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Nature, and the Nature Conservancy Canada in April 2010, based on the following methodology:

Inventory gaps identified by the Recovery Team were surveyed in 2004-2009 to support the identification of critical habitat (Jalava 2004-2008; Jones 2004-2008). All occurrence data for Hill’s Thistle for the Bruce Peninsula and Wasaga Beach Provincial Park, and for protected areas in the Manitoulin Region were gathered from all available sources (especially NHIC and BPNP data bases, as well as Wasaga Beach monitoring data). All records were scrutinized and updated in October 2009 and April 2010 by Parks Canada. Only records with coordinates taken on the ground with GPS or localities mapped very precisely in the field on aerial photography were used. Records without GPS coordinates, or not field mapped on air or satellite imagery, or records with only vague locations, were not used to identify critical habitat.

In almost all cases newer georeferenced observations were available and supercede these records.

For the Bruce Peninsula and Wasaga Beach: All occurrence data for Hill’s Thistle on the Bruce Peninsula (except those on First Nations lands) and at Wasaga Beach Provincial Park were plotted digitally on 2006 ortho photography with 30 cm resolution (South Western Ontario Orthorectification Project 2006). Suitable alvar community polygons as mapped by Jalava (2008a) were superimposed on this. Field data were available for most records to tell if the plants were spread throughout the vegetation community despite having only a single centroid UTM coordinate.

For the Manitoulin Region: All occurrence data from protected areas were superimposed on Quickbird imagery (6 satellite images at 60 cm resolution with a date range of June 2005 – August 2008). As well, field mapping from hard copies (IACI unpublished field notes 1995 and 1996 on file in NHIC database) was scanned and superimposed on satellite imagery to show field-mapped locations. Again, field data were available to tell if the plants represented a single point or were spread throughout.

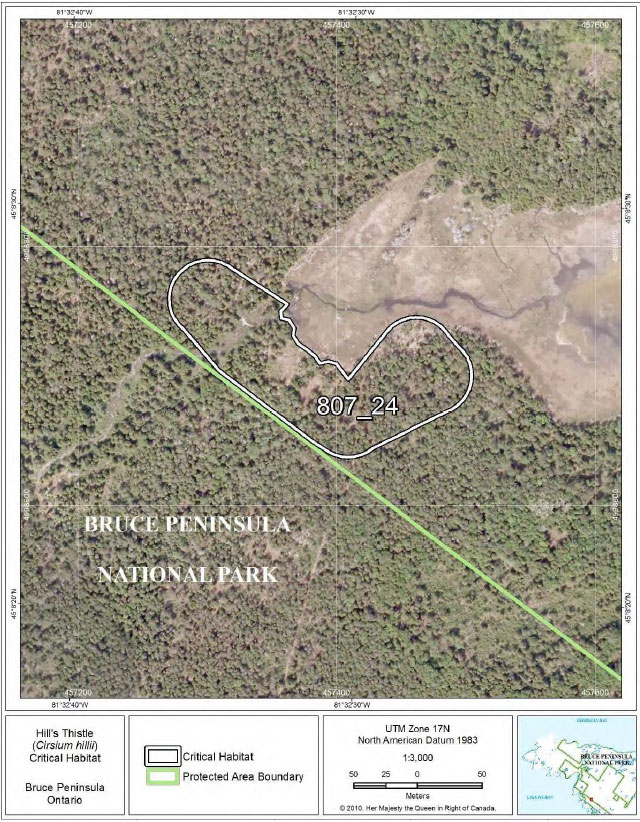

For the entire Canadian range: The species occupies edges and openings where substrate and other factors are suitable, and fluctuations of some factors may cause population size to wax and wane. Therefore, some radial distance around the plants (to allow for dispersal and expansion of the population and to provide shelter and edge habitat) must be identified as critical habitat. A radial measure of 30 m around the plants was derived in the field by a core group of the Recovery Team as the distance required to prevent impact to extant populations and habitat. Using GIS software, a 30 m circle was plotted around all single point occurrences. In cases where 30 m circles overlapped, they were joined to form one polygon. In cases where 30 m circles were less than 30 m apart, they were joined if the intervening land contained suitable habitat. In cases where a centroid was provided for a population known to be >50 plants but the locations of individual plants in the habitat were not known, if the suitable habitat patch was larger than a 30 m radius circle, the entire area of suitable habitat was considered critical habitat.

Biophysical attributes of critical habitat for Hill’s Thistle in Canada include the following:

- Dry, open ground with little or no immediate canopy cover;

- Trees if present are predominantly coniferous species in a savanna or very open woodland situation;

- Patches of low grasses or sedges, especially Poverty Oat Grass (Danthonia spicata) and Richardson’s Sedge (Carex richardsonii), and reindeer lichens (Cladina rangiferina and C. mitis), or Bearberry with scattered shrubs;

- Habitat patches are often found on edges and in openings, especially the edges of alvars and in trails;

- Soils are generally shallow and range from sandy near Lake Huron to silty and slightly alkaline on alvars.

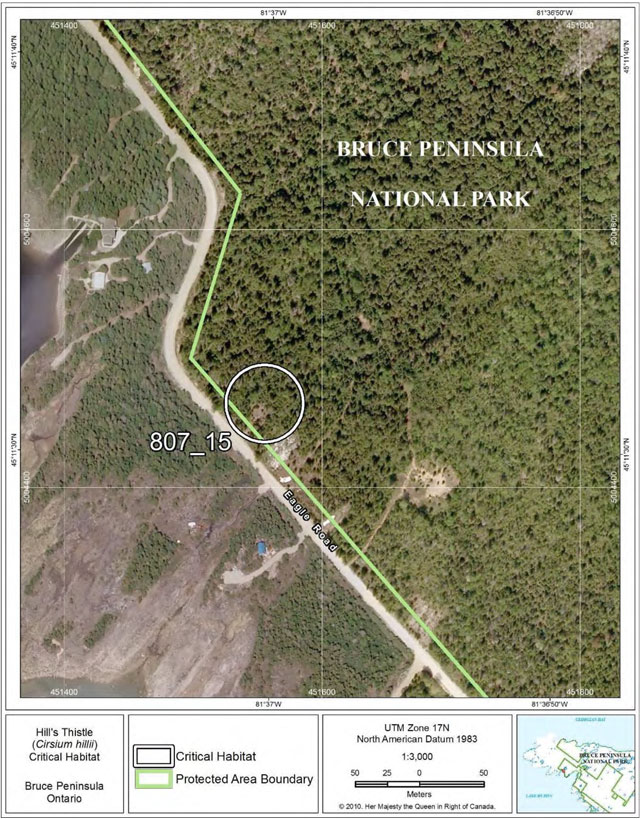

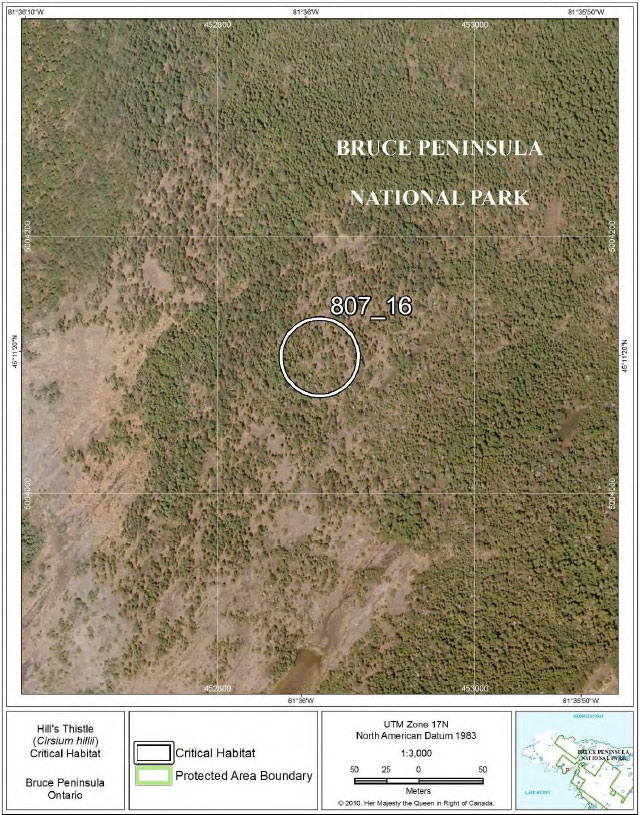

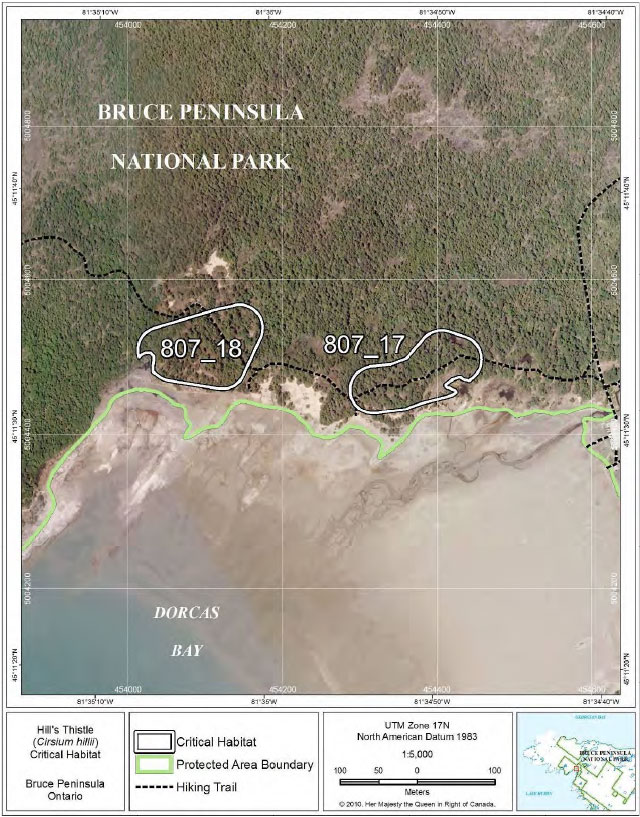

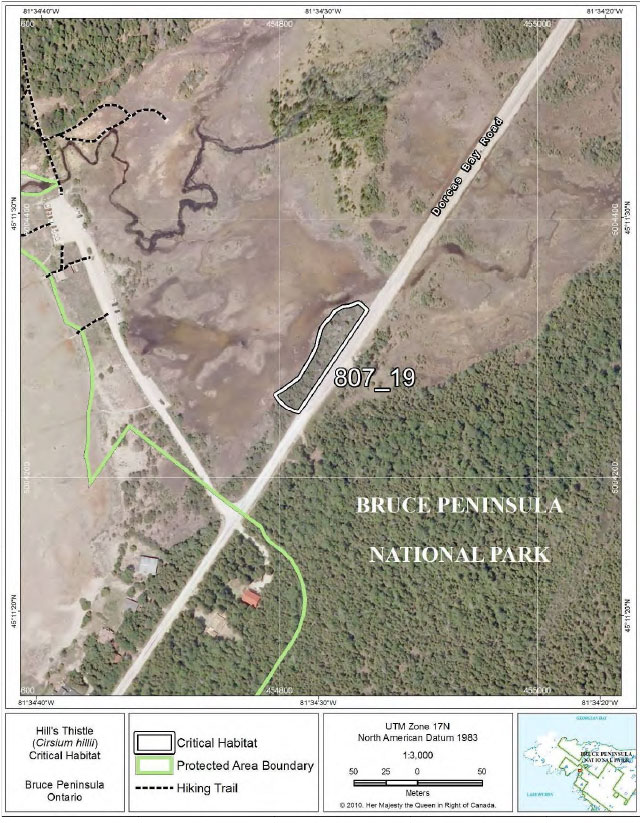

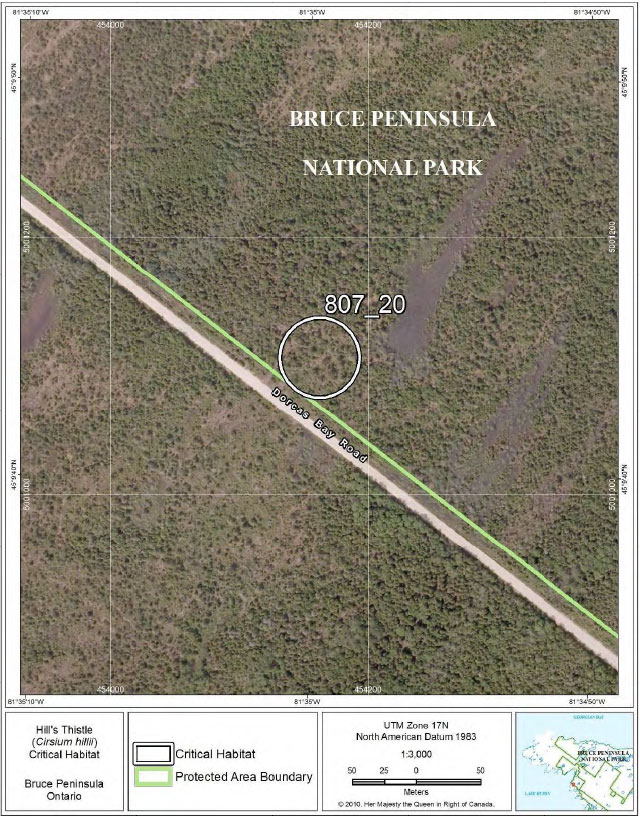

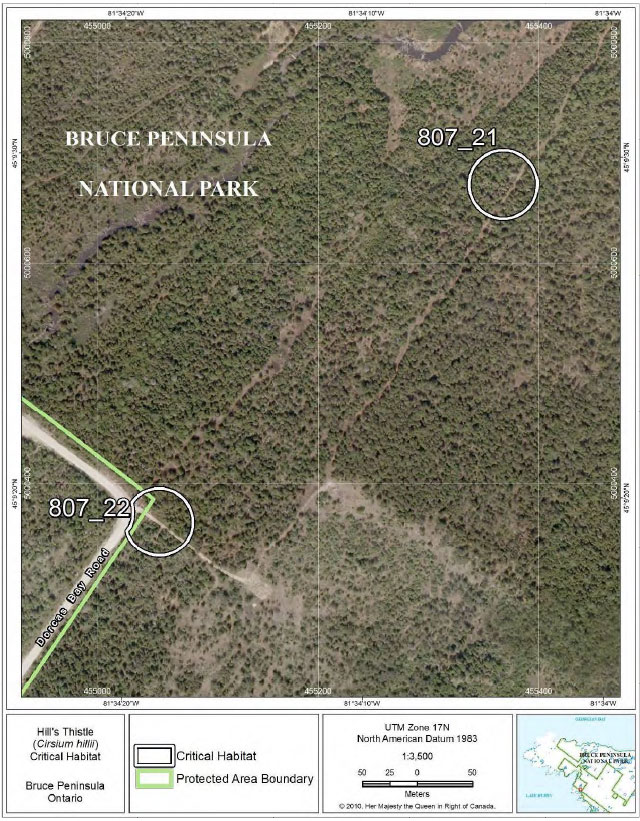

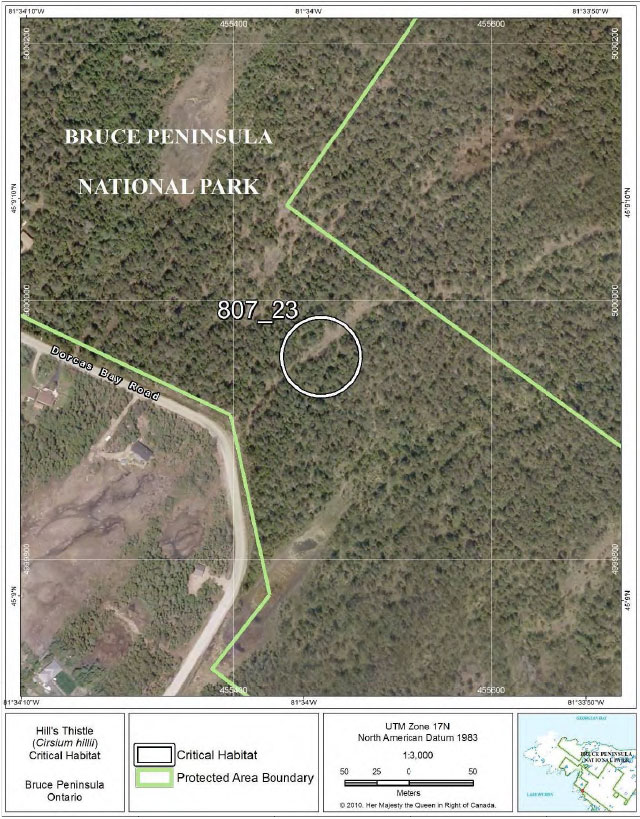

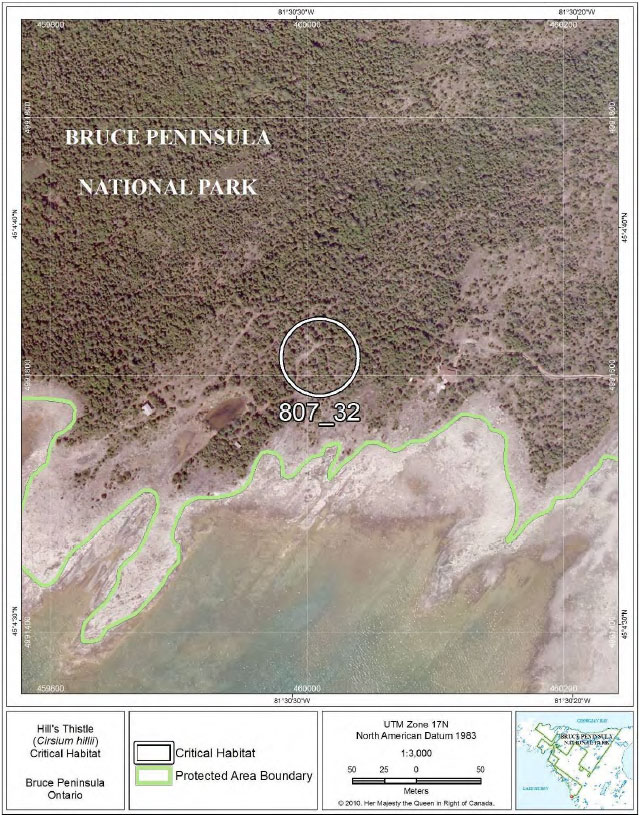

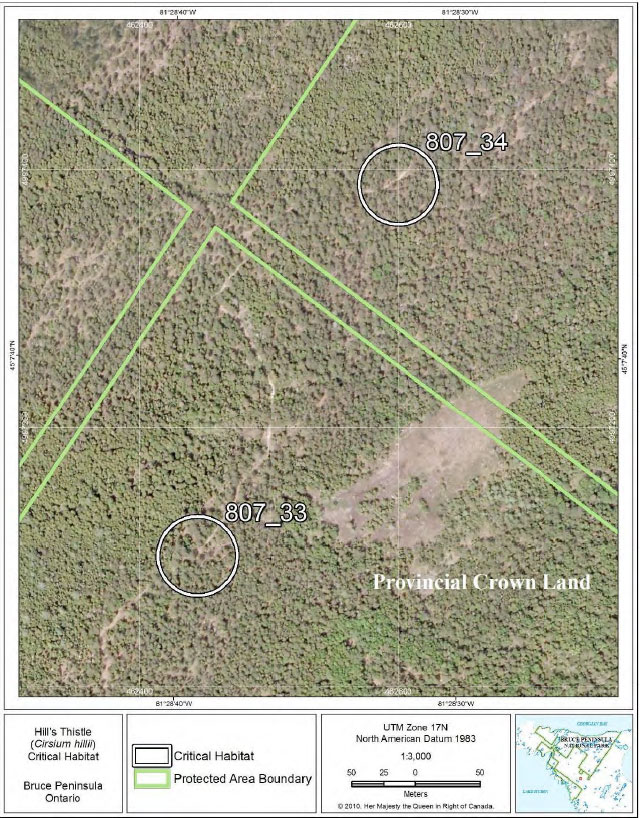

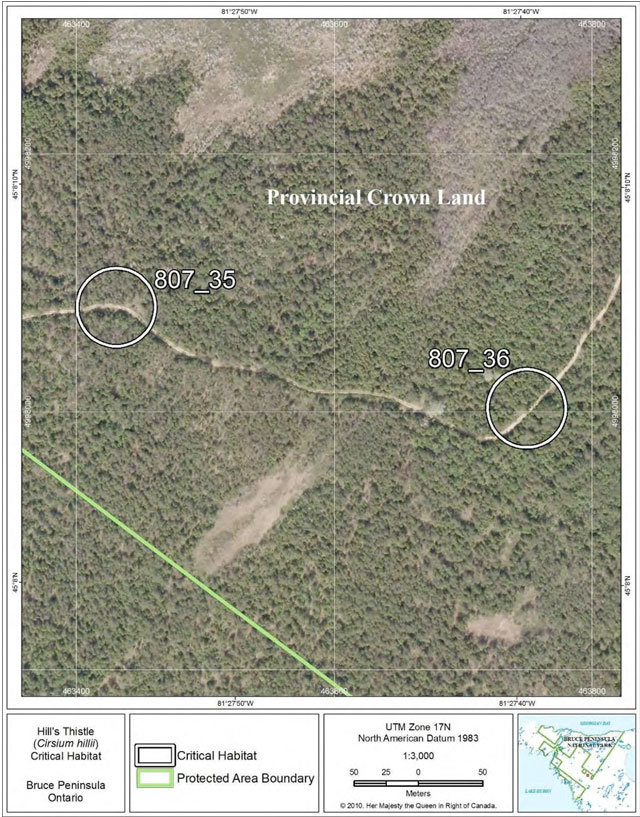

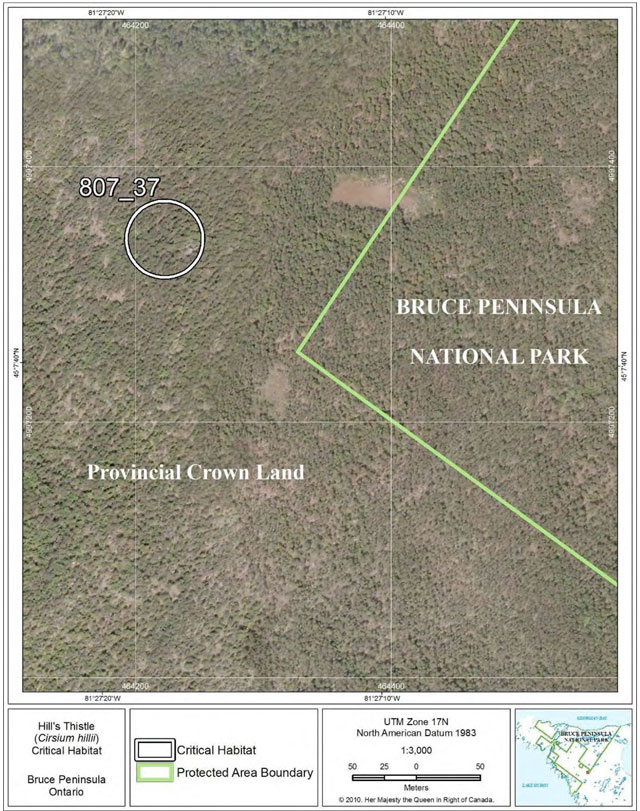

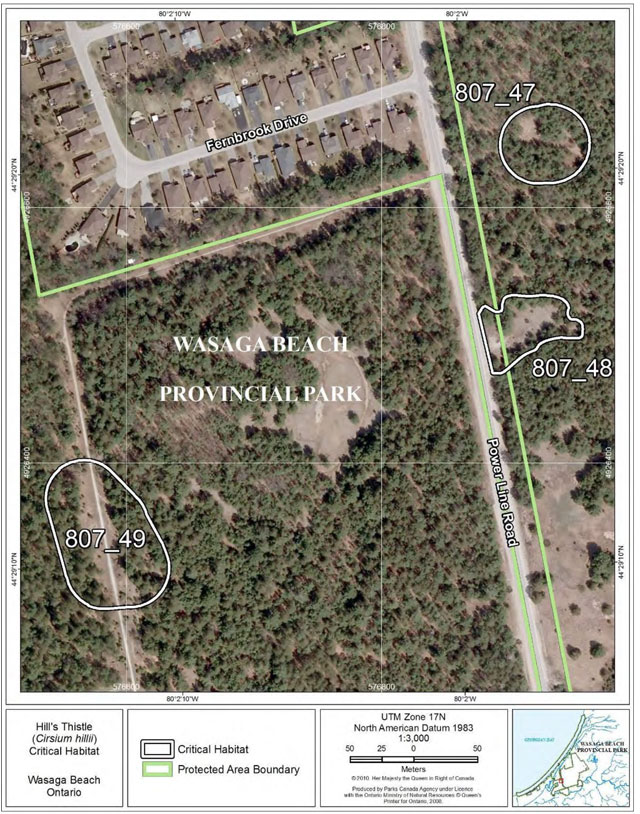

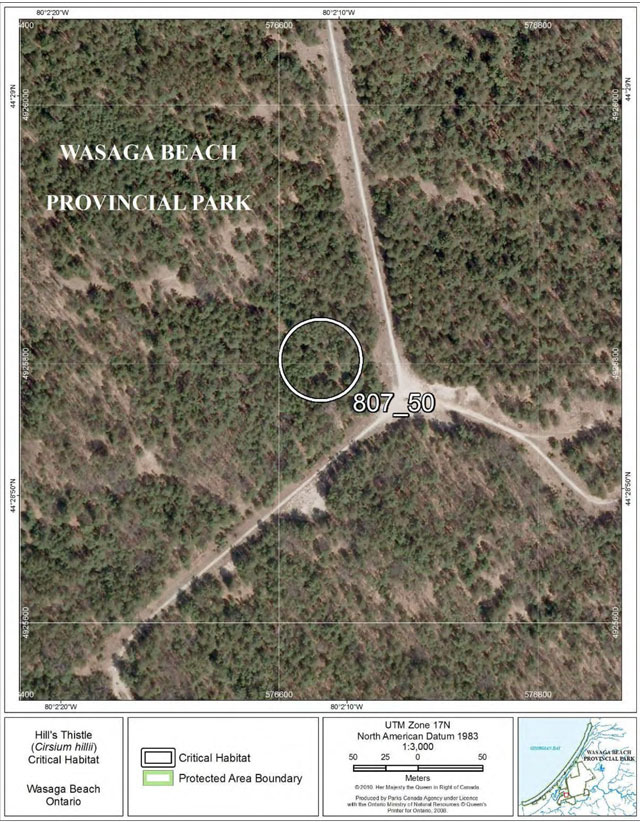

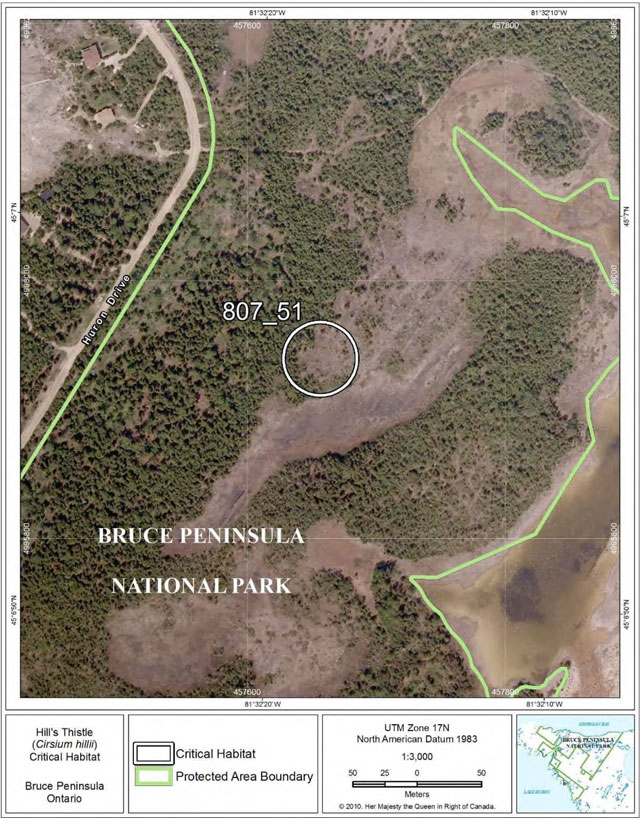

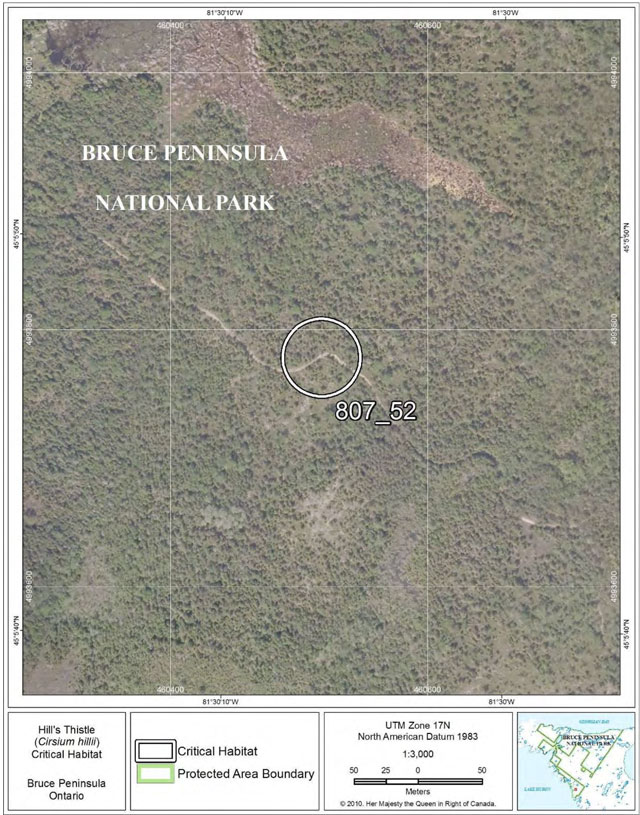

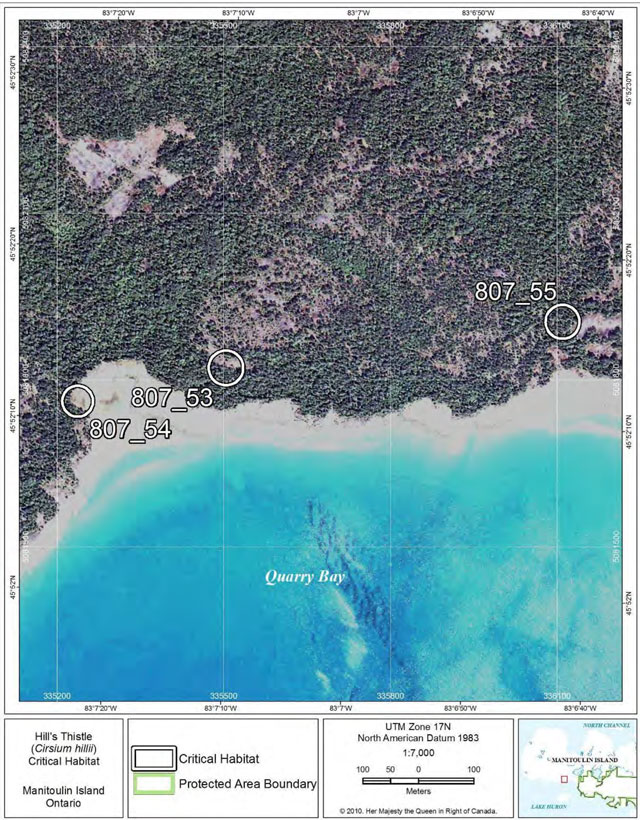

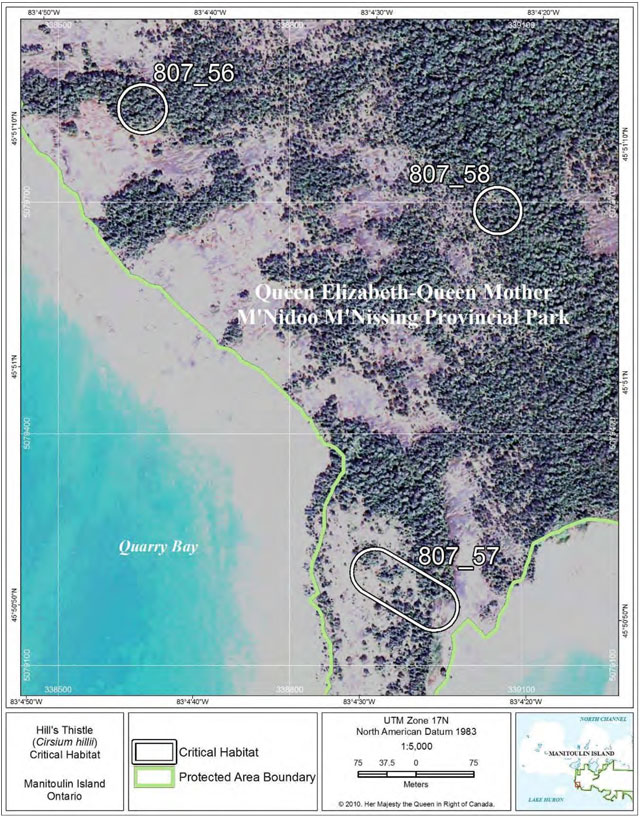

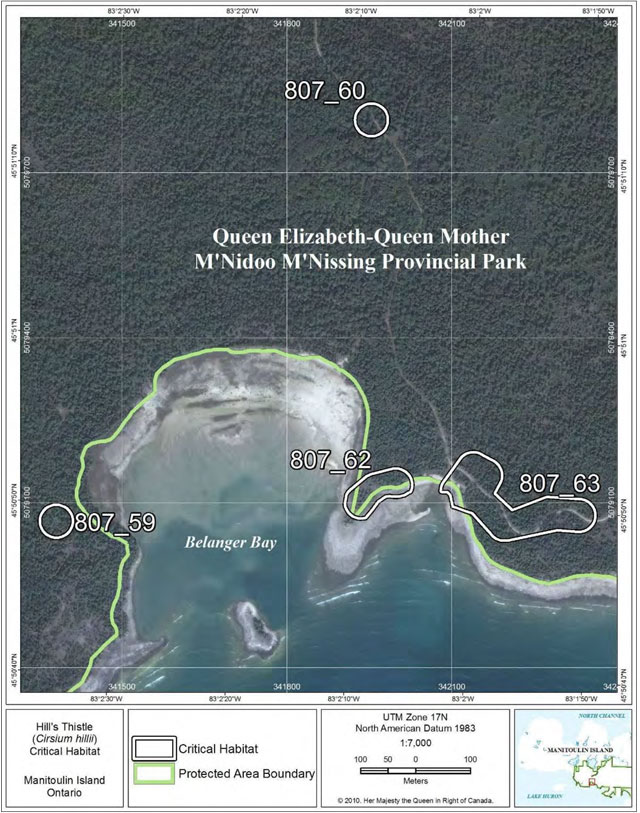

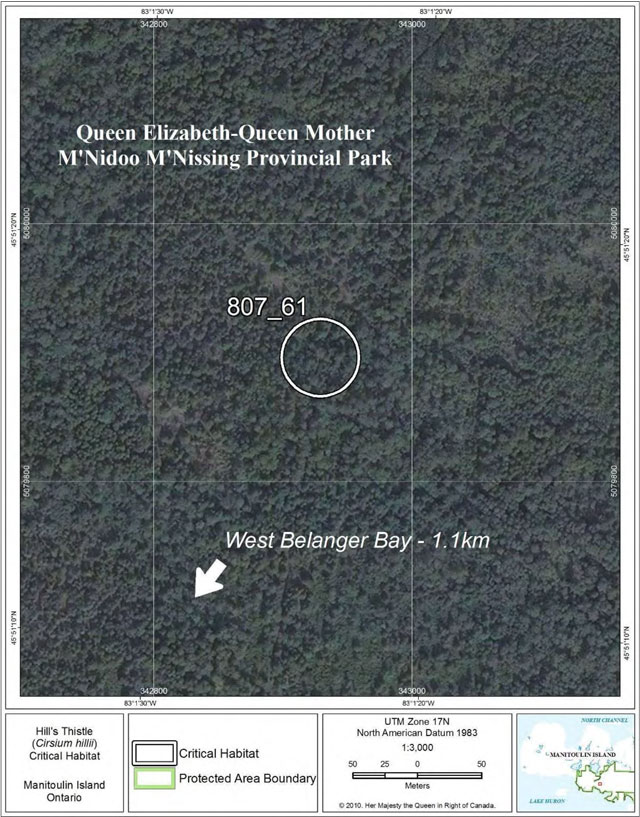

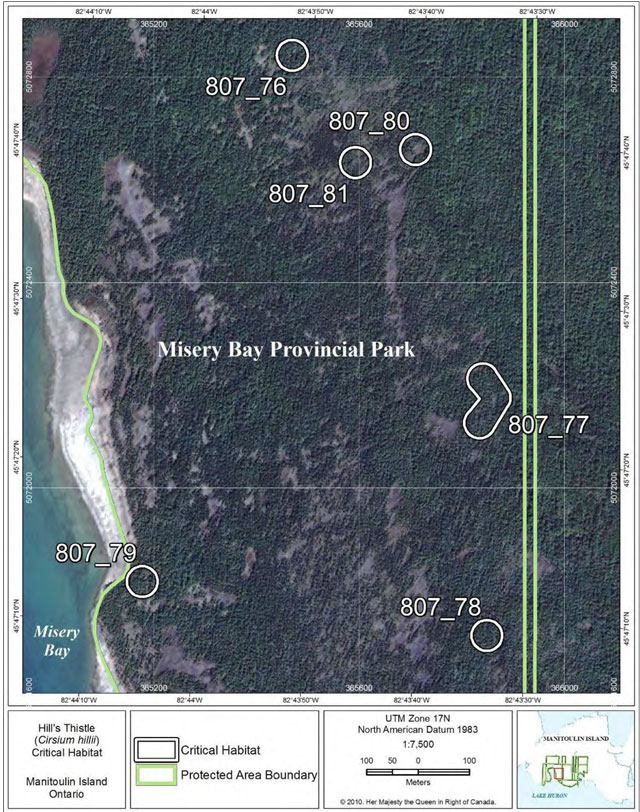

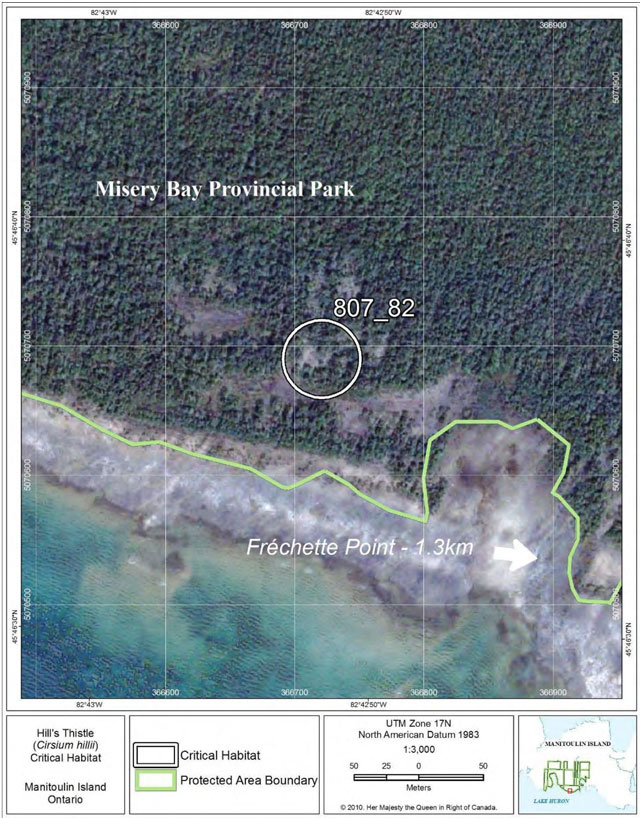

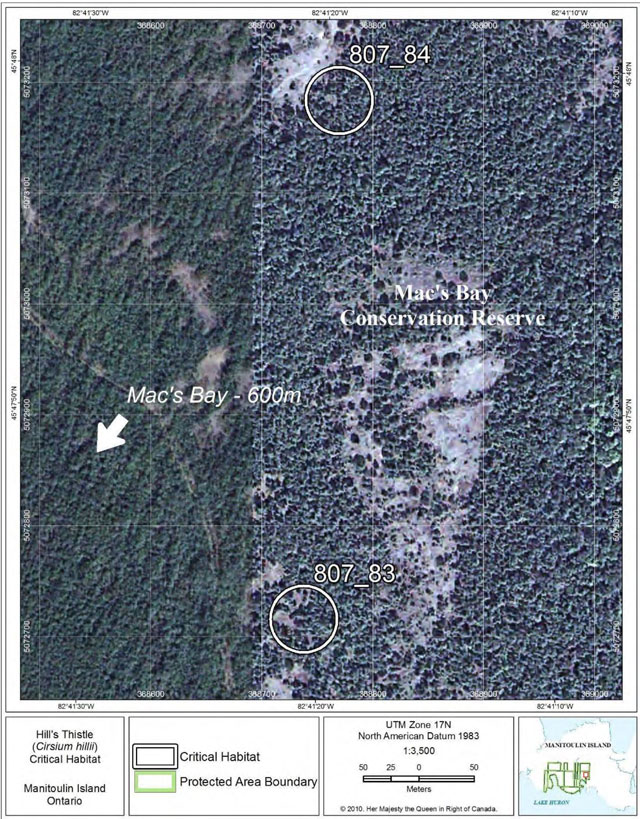

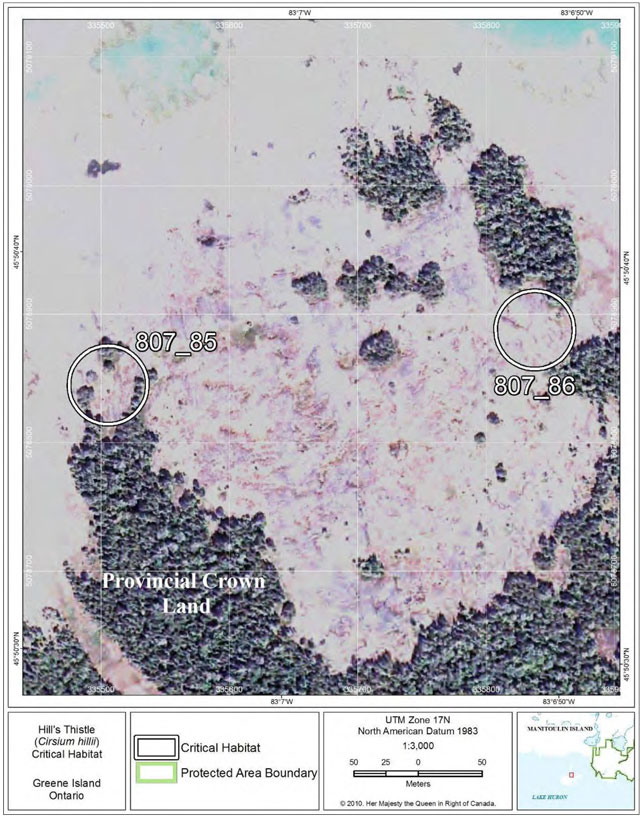

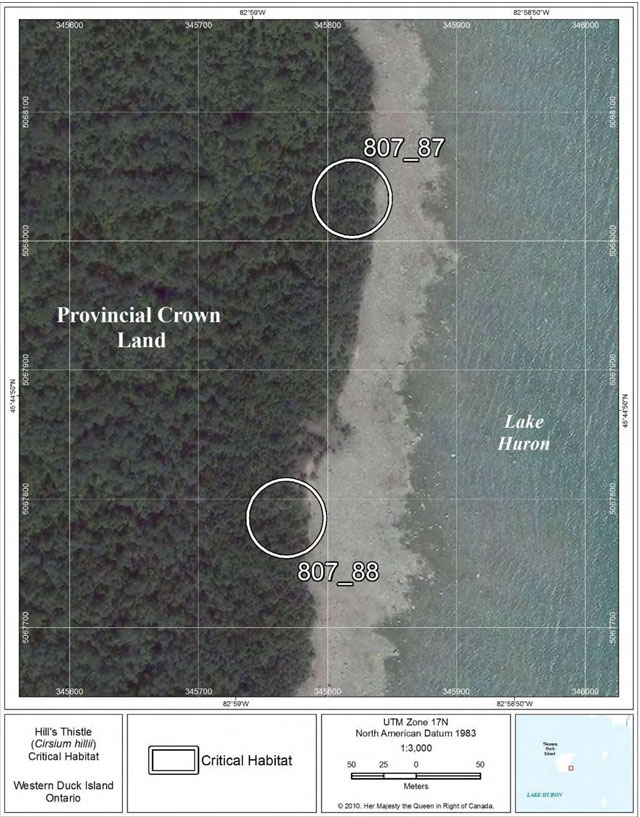

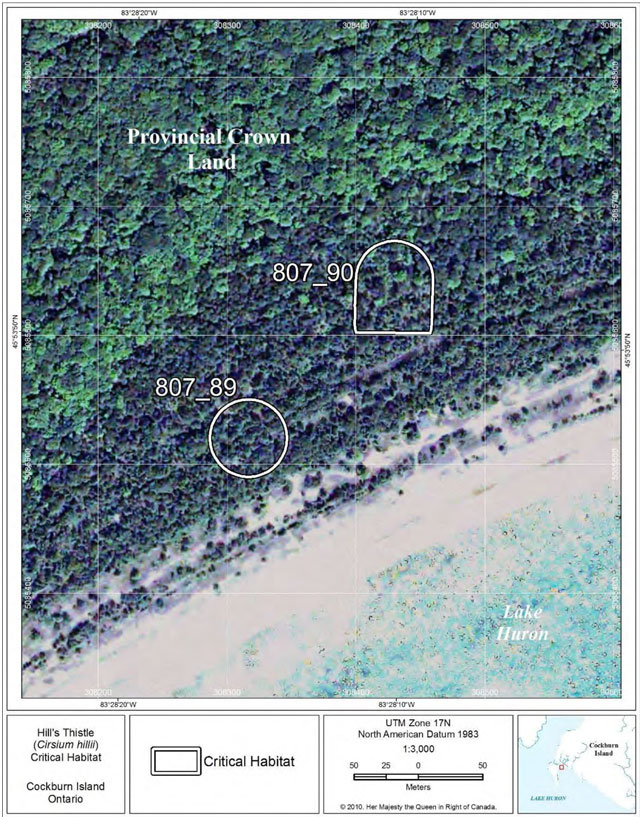

In total, 90 polygons of critical habitat, collectively covering 41 hectares at 17 sites, are identified here. Some sites have more than one polygon. The general locations of critical habitat polygons are depicted in Figures 3, 4 and 5 with detailed maps showing the extent of each critical habitat polygon provided in Appendix D. GIS shapefiles of all critical habitat polygons are maintained by the Federal Government.

2.4.3 Activities likely to destroy critical habitat

Examples of activities that are likely to result in the destruction of Hill’s Thistle critical habitat are listed here with the habitat features or properties they are likely to destroy. These activities would be destructive in any part of critical habitat, because they may damage or destroy Hill’s Thistle plants, damage or remove the substrate required for growth, introduce competition, or interrupt natural processes that maintain habitat.

Activities that destroy or remove native grassy vegetation:

- Building cottages, houses, and driveways over critical habitat patches

- Building roads across critical habitat

- Limestone/dolostone quarrying or extraction of surface materials such as boulders

- Clearing of ground

- Using critical habitat as landing areas or roads during the logging of adjacent forests

Activities that disturb the extremely shallow soil:

- Driving heavy machinery across critical habitat

- Off-trail ATV or mountain bike use

Activities that reduce native species presence by introducing exotic or potentially invasive species:

- Trucking-in fill dirt and gravel

- Off-trail ATV use as a vector for weeds

- Seeding lawns or planting non-native species

- Planting trees of any kind

- Grazing of livestock

- Feeding hay to livestock in critical habitat

Activities that trample and damage vegetation and soil:

- Off-trail use by hikers at a level that tramples or destroys vegetation

- Camping activities such as placing a tent, fire pit, or latrine on top of critical habitat patches

- Off-trail use of critical habitat for group events.

There are several instances where trail use is beneficial to Hill’s Thistle because the light disturbance keeps the ground clear of other vegetation. Threshold levels at which trail usage could become harmful rather than beneficial have not been determined. Thus, it is intended here that in general the use of existing trails and roads within critical habitat may continue. The determination of the point at which trail usage may potentially become harmful and protective action needed is more appropriately handled by land managers on a site by site basis.

2.4.4 Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

Future identification of critical habitat elsewhere in the range of Hill’s Thistle will be undertaken as needed to ensure population and distribution objectives are met, or if the degree of risk affecting the species increases. Table 3 outlines and explains the work required to enable further critical habitat identification and mapping.

Table 3. Schedule of Studies

| Description of Activity | Outcome/Rationale | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Update occurrence data & mapping for all remaining sites to current CH standards. | Complete and current occurrence data set & mapping permits creation of accurate CH polygons for remaining Bruce Peninsula & Manitoulin Region populations. | 2013. Could complement fieldwork for COSEWIC Status Report Update due in 2014 |

| Identify CH parcels to meet the population & distribution objectives. | The amount & distribution of critical habitat required to meet recovery objectives is mapped. | As required |

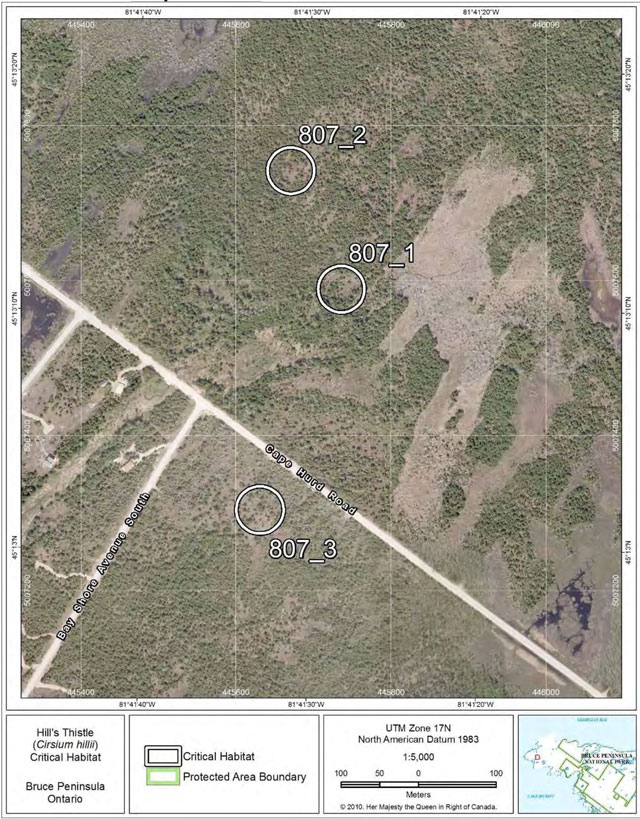

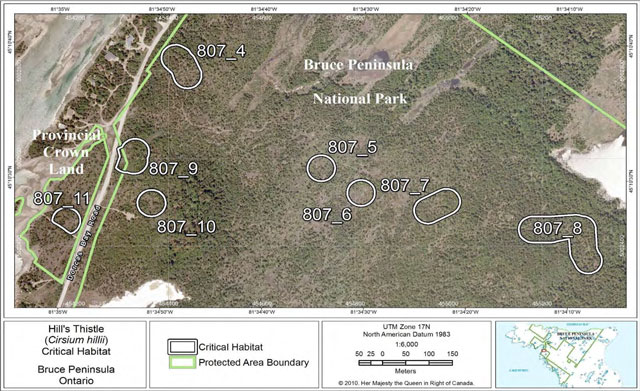

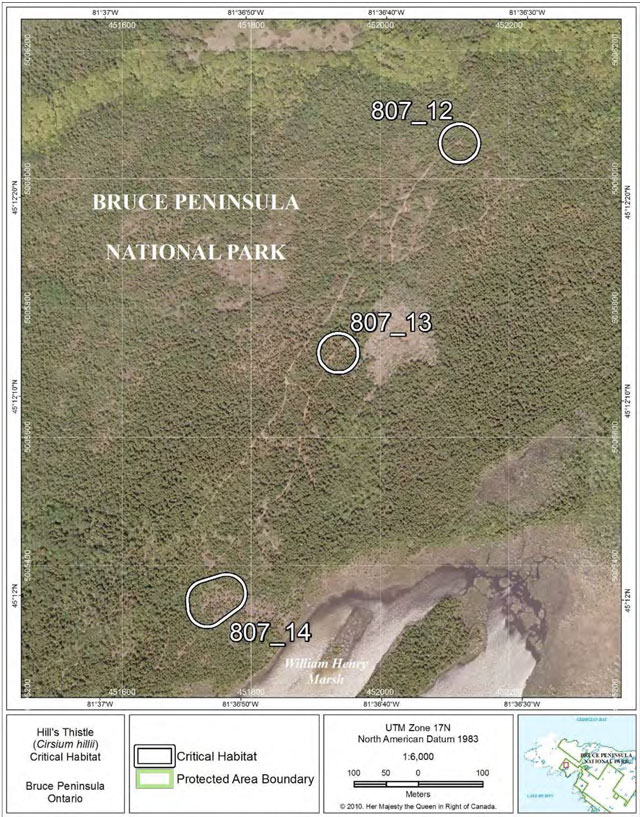

Figure 4. General Locations of Critical Habitat Polygons on the Bruce Peninsula

Figure 5. General Locations of Critical Habitat Polygons in the Manitoulin Region

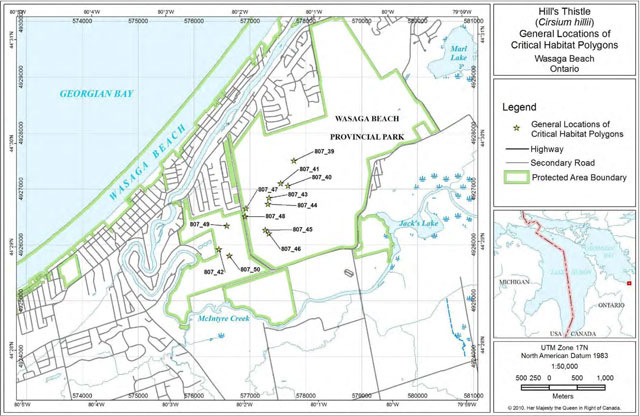

Figure 6. General Locations of Critical Habitat Polygons at Wasaga Beach

2.5 Habitat conservation

Critical habitat is identified for a total of 17 Hill’s Thistle sites found wholly or partly within protected areas

Bruce Peninsula:

- Brinkman’s Corner (Public Works Canada)

- Bruce Peninsula National Park

- Clarke Property-Baptist Harbour (Ontario Heritage Foundation; Ontario Heritage Trust) Dorcas Bay Road (Crown Land)

- Johnston Harbour - Pine Tree Point ANSI (Crown Land)

- Johnston Harbour - Pine Tree Point Provincial Park (Bruce Peninsula National Park) Lyal Island (Ontario Nature)

- Rover Property (Nature Conservancy of Canada)

- Williams Property-Baptist Harbour (Escarpment Biosphere Conservancy)

Manitoulin Island:

- Macs Bay Conservation Reserve

- Misery Bay Provincial Nature Reserve

- Quarry Bay Nature Reserve (Ontario Nature)

- Queen Elizabeth-Queen Mother M'nidoo M'nissing Provincial Park

Islands surrounding Manitoulin:

- Greene Island (Crown Land)

- Cockburn Island, Wagosh Bay (Nature Conservancy Canada) Western Duck Island (Crown Land)

Wasaga Beach:

- Wasaga Beach Provincial Park

2.6 Measuring progress

Evaluation of the progress toward achieving Hill’s Thistle recovery will be reported five years following final posting of this recovery strategy on the Species at Risk Public Registry, and every five years following, as per SARA (s. 46). The success of Hill’s Thistle recovery will be evaluated by comparing information from monitoring and inventory with the population and distribution objectives as per Table 4.

Table 4. Performance measures for progress of Hill’s Thistle recovery

| Criterion | Links to Objective # | Evaluation Timeframe (years after final posting of recovery strategy) |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring program implemented for all priority sites. | 1, 2 | 3 |

| Some forms of habitat protection begun to be put in place (protective park management, etc.). | 1, 2 | 5 |

| Threats assessment completed and an evaluation of how to address current threats. | 1, 2 | 3 |

| Threats to habitat begin to be addressed e.g. barriers to prevent ATV use or visitor trampling. | 1, 2 | 2 |

| A multi-species communications strategy developed for the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Region, with information distributed to private landowners about stewardship practices. | 1, 2 | 5 (CS) 5+ (outreach info.) |

| A dialogue begun with First Nations, municipalities, and corporate quarry owners, about stewardship possibilities. | 1, 2 | 3 |

| No continuing decline in total number of mature individuals | 1 | Measured over 10 years or 3 generations* |

| Populations are maintained in each of the 4 core areas | 2 | Measured over 10 years or 3 generations |

* This time frame is adopted from the COSEWIC assessment criteria, to account for anomalies within a shorter time frame.

2.7 Statement on action plans

One or more action plans will be completed by December 2015.

3. References

Brownell, V.R. and J.L. Riley. 2000. The Alvars of Ontario: Significant Natural Areas in the Ontario Great Lakes Region. Federation of Ontario Naturalists, Don Mills, Ontario. 269 pp.

Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island Alvar Recovery Team. 2009. Identification of Hill’s Thistle critical habitat: justification for boundaries of individual polygons. Unpublished document available from the chairman of the recovery team. Parks Canada, Ottawa. 8 pp and accompanying database and shape files.

Catling, P.M. 1995. The extent of confinement of vascular plants to alvars in Southern Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 109:172-181.

COSEWIC. 2004. COSEWIC status report on Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 40 pp.

COSEWIC. 2009. Wildlife Species Assessment. COSEWIC's Assessment Process and Criteria. Government of Canada.

COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC Wildlife Species Search – Hill’s Thistle. Government of Canada.

Endangered Species Act. 2007. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Online at Species at Risk website

Environment Canada. 2005. Policy on the Feasibility of Recovery in Renew Recovery Handbook (Roman), working draft. Recovery Secretariat, Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.

Environment Canada. 2009. Hill’s Thistle page. Accessed November 5, 2009.

Gaiser, L.D. 1966. A Survey of the Vascular Plants of Lambton County, Ontario. Compiled by Raymond J. Moore. Ottawa: Plant Research Institute, Research Branch, Canada Department of Agriculture. 122pp.

Higman, P.J. and M.R. Penskar. 1999. Special plant abstract for Cirsium hillii (Hill’s Thistle). Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 2 pp. Online at http://web4.msue.msu.edu/mnfi/abstracts/botany/Cirsium_hillii.pdf [link inactive].

Hill, E.J. 1910. The pasture-thistles, east and west. Rhodora 12:211-214.

Hilty, J. 2008. Insect visitors of prairie wildflowers in Illinois. Online at http://www.shout.net-~jhilty/ [link inactive].

International Alvar Conservation Initiative. 1996. Conserving Great Lakes Alvars. Final Technical Report of the International Alvar Conservation Initiative. The Nature Conservancy, Chicago, Illinois.

Jackson, J. 2004. Wasaga Beach Provincial Park. Prescribed burn report 2004. Ontario Parks, Ministry of Natural Resources. Unpaginated.

Jalava, J.V. 1998. Alvar stewardship packages. Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre Newsletter 4(2):14.

Jalava, J.V. 2004. Biological Surveys of Bruce Peninsula Alvars. Prepared for NatureServe Canada, Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre and Parks Canada. iii + 21 pp.

Jalava, J.V. 2005. Biological surveys of Bruce Peninsula Alvars, summary report. Unpublished report, Prepared for Bruce Peninsula National Park, Parks Canada. iii + 80 pp.

Jalava, J.V. 2007. Species at Risk Inventory: Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii). Prepared for Parks Canada Agency, Bruce Peninsula National Park / Fathom Five National Marine Park, Tobermory, Ontario. 15 pp.

Jalava, J.V. 2008a. Alvars of the Bruce Peninsula: A Consolidated Summary of Ecological Surveys. Prepared for Parks Canada, Bruce Peninsula National Park, Tobermory, Ontario. iv + 350 pp + appendices.

Jalava, J.V. 2008b. Summary of Updated Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) Occurrence Data in Bruce County. Unpublished report to Bruce Peninsula National Park, Parks Canada, Tobermory. 2 pp.

Janke, K., C. Homuth and M. Lake. 2006. Hill’s Thistle (Cirsium hillii) monitoring, Wasaga Beach Provincial Park, 2006. Ontario Parks, Ministry of Natural Resources. Unpaginated.

Jones, J. 1995. International Alvar Conservation Initiative field data form for Evansville Shrub Alvar, on file at the Natural Heritage Information Centre, Peterborough, Ontario.

Jones, J. 1995-2009. Field data forms (1995-1998 from the International Alvar Conservation Initiative) on file at the Natural Heritage Information Centre, Peterborough, Ontario.

Jones, J.A. 1998. Manitoulin’s Flat Rock Country: a landowner’s guide to a special habitat. Federation of Ontario Naturalists, Don Mills, Ontario. 17 pp.

Jones, J.A. 2000. Fire history of the bur oak savannas of Sheguiandah Township, Manitoulin Island. Michigan Botanist 39(1): 3-15.

Jones, J.A. 2004. Alvars of the North Channel Islands. Report to NatureServe Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.

Jones, J.A. 2005. More alvars of the North Channel Islands and the Manitoulin Region: Report prepared for Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Espanola Office.

Jones, J.A. 2006a. Report from field work on Iris lacustris and Cirsium hillii in the Manitoulin Region in 2006. Report prepared for Parks Canada, Species at Risk Section, Peterborough, Ontario.

Jones, J.A. 2007. Report from the 2007 Species-At-Risk surveys on the Wikwemikong Reserve. Unpublished report to the Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve on file with the Wikwemikong Lands Office.

Jones, J.A. 2008. Report from field work on Hill’s Thistle in Manitoulin and Algoma Regions in 2008. Unpublished report to Parks Canada, Ottawa. 6 pp.

Parks Canada Agency. 2010. Recovery Strategy for Lakeside Daisy (Hymenoxys acaulis) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Parks Canada Agency, Ottawa. 71 pp.

Jones, J.A. and C. Reschke. 2005. The role of fire in Great Lakes alvar landscapes. The Michigan Botanist (44) 1: 13-27.

Kell, David J. 2006. Cirsium. In: Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 19. Oxford University Press.

Lee, H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig, and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Sciences Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch. SCSS Field Guide FG-02.

Ministry of Municipal Affairs & Housing. 2005. Provincial Policy Statement. Issued under Section 3 of the Planning Act. 37 pp.

Moore, R.J. and C. Frankton. 1974. The Thistles of Canada. Monograph No. 10, Canada Department of Agriculture, Research Branch, Ottawa. 111 pp.

Morton, J.K. and J.M. Venn. 2000. The Flora of Manitoulin Island, 3rd ed. University of Waterloo Biology Series Number 40. Waterloo, Ontario.