Pitcher’s Thistle Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the Pitcher’s Thistle, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Parks Canada Agency. Ottawa. x + 31 pp

Additional copies:

Additional copies can be downloaded from the SARA Public Registry.

Cover photo: ©Rafael Otfinowski

Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du chardon de Pitcher (Cirsium pitcheri) au Canada»

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2010. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-100-17326-9

Catalogue no.: En3-4/88-2011E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source

Recommendation and approval statement

Recommended by: (signed by) Robin Heron

Park Manager Pukaskwa National Park of Canada

Approved by: (signed by) Mike Walton

Field Unite Superintendent, Northern Ontario Field Unit

Approved by: (signed by) Alan Latourelle

Chief Executive Officer, Parks Canada

The Parks Canada Agency led the development of this federal recovery strategy, working together with the other competent minister(s) for this species under the Species at Risk Act. The Chief Executive Officer, upon recommendation of the relevant Park Superintendent(s) and Field Unit Superintendent(s), hereby approves this document indicating that Species at Risk Act requirements related to recovery strategy development (sections 37-42) have been fulfilled in accordance with the Act.

All competent ministers have approved posting of this recovery strategy on the Species at Risk Public Registry.

Declaration

Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife at risk throughout Canada. The Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c. 29) (SARA) requires that federal competent ministers prepare recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened species.

The Minister of the Environment presents this document as the recovery strategy for the Pitcher’s Thistle under SARA. It has been prepared in cooperation with the jurisdictions responsible for the species, as described in the Preface. The Minister invites other jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved in recovering the species to use this recovery strategy as advice to guide their actions.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best existing knowledge and are subject to modifications resulting from new findings and revised objectives.

This recovery strategy will be the basis for one or more action plans that will provide further details regarding measures to be taken to support protection and recovery of the species. Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the actions identified in this strategy. In the spirit of the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, all Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the species and of Canadian society as a whole. The Minister of the Environment will report on progress within five years.

Contributors

Prepared by Judith Jones, Jarmo Jalva and Brian Hutchinson, with input from the Pitcher’s Thistle – Dune Grasslands Recovery Team.

Acknowledgements

Dedication: The Pitcher’s Thistle - Dune Grasslands Recovery Team hereby dedicates this recovery strategy in memory of two of its dedicated members, Dr. Anwar Maun (1935-2007), Professor Emeritus, University of Western Ontario, and Dr. John Morton (1928-2011), Professor Emeritus, University of Waterloo. Their tireless efforts in the conservation of dune systems and Pitcher’s Thistle, is a continuing inspiration to us all.

Thanks are due to Brian Hutchinson, past chair of the Recovery Team (2001-2005), and Will Kershaw, past co-chair (2001-2004). Bob Gray and Karen Hartley (both of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources–OMNR ), lent their administrative skills in support of the Team. Many past Recovery Team members are thanked: Robin Bloom (CWS), Linda Chiupka (Parks Canada), Terry Crabe (Consultant), Burke Korol (Ontario Parks), Andrew Promaine (Parks Canada Agency), and the late Dr. Anwar Maun (University of Western Ontario). Thanks to these Technical Advisors for their many contributions: Dr. Marlin Bowles (Morton Arboretum, Lisle Illinois), Dr. Steve Marshall (University of Guelph), Mike Oldham (OMNR ), Geoff Peach (The Lake Huron Centre for Coastal Conservation), Mike Penskar (Michigan Natural Features Inventory), and Don Sutherland (OMNR).

In addition, the following individuals and their organizations contributed expertise, time or information to this recovery strategy: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR ), Midhurst District; Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre (OMNR ); Kara Brodribb (OMNR / Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC)); Laura Bjorgan (OMNR); Dave Loftus (OMNR); Rodger Leith (OMNR ); and John Riley (NCC). Peer reviews of the draft recovery strategy were undertaken by two anonymous reviewers. Team member Jane Bowles contributed significantly to the development of the original draft.

Thanks also to the network of volunteers and landowners on Manitoulin Island for on-the-ground monitoring work that has helped inform this strategy.

Pitcher’s thistle Dune Grasslands recovery team

Gary Allen, Parks Canada Agency, Recovery Team Chair

Norah Toth, Ontario Parks, Recovery Team Co-Chair

Wasyl Bakowsky, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Holly Bickerton, Consulting Biologist

Dr. Jane Bowles, University of Western Ontario

Eric Cobb, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Martha Coleman, University of Hawaii at Manoa

Dr. Robin Davidson-Arnott, University of Guelph

Talena Kraus, Ecological Consultant

Alistair MacKenzie, Ontario Parks

Angela McConnell, Canadian Wildlife Service

Dr. John Morton, University of Waterloo

Dr. Rafael Otfinowski, Parks Canada Agency

Chris Risley, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Suzanne Robinson, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Strategic environmental assessment statement

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery strategies, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that recovery actions may inadvertently lead to effects in the natural environment beyond the intended benefits. The results of the SEA are summarized below and briefly outline the potential positive and negative environmental impacts as a result of the proposed recovery strategy and resultant mitigation.

The most effective methods of recovery will be to reduce or eliminate threats to the dune ecosystems that are the habitat of Pitcher’s Thistle. This approach will seek to maintain dunes in a natural state, thus protecting the habitat for other dune species as well. By maintaining the processes that keep dunes dynamic, a variety of dune stages are maintained, providing sufficient habitat for many other species (at least 46 rare or at-risk species are known to occur on dunes on Lake Huron or Lake Superior in Ontario).

Furthermore, most approaches proposed in this recovery strategy involve outreach, education, use of policy, as well as research, inventory, and monitoring, which have little or no environmental impact. In addition, recovery action planning will be coordinated with other recovery teams, further reducing the likelihood of negative impacts to any listed species-at-risk. No significant negative impacts to the natural environment are expected from this recovery strategy.

Specific activities within National Parks, such as population control of deer or geese, or removals of exotic species such as Common Reed (Phragmites australis), may require further assessment under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA).

A more detailed discussion is contained in Appendix A Effects on the Environment and Other Species.

Residence

SARA defines residence as: a dwelling-place, such as a den, nest or other similar area or place that is occupied or habitually occupied by one or more individuals during all or part of their life cycles, including breeding, rearing, staging, wintering, feeding or hibernating [Subsection 2(1)]. The concept of residence under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) does not apply to this species. Residence descriptions, or the rationale for why the residence concept does not apply to a given species, are posted on the SARA public registry: http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/ sar/recovery/residence_e.cfm [link no longer active].

Preface

The Species at Risk Act (SARA, Section 37) requires the competent Minister to prepare a recovery strategy for all listed Extirpated, Endangered or Threatened species. The Parks Canada Agency and Environment Canada (on behalf of the competent minister) co-led the development of this recovery strategy with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, in cooperation and consultation with the Pitcher’s Thistle – Dune Grassland Recovery Team. The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Ontario Parks, and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources reviewed the document. The proposed strategy meets SARA requirements in terms of content and process (Sections 39-41).

Recovery feasibility summary

Recovery of Pitcher’s Thistle is technically and biologically feasible based on the four criteria outlined in the draft Government of Canada SARA policy (s.40):

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

Biologically, this, species has many large, self-sustaining populations and sites where thousands of individuals are present (see Appendix B). Dramatic increases in population size have been documented in recent years, so the species is capable of accomplishing sufficient reproduction for recovery. There are sufficient numbers to improve population sizes when there is adequate habitat and threats are not present.

- Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

Many large areas of high quality habitat remain, and many sites in the Manitoulin Region are remote, pristine, and have very few or no threats present. Habitats along the southern Lake Huron coast have had more t human impact but remain suitable and not occupied to capacity. Some small sites in the Manitoulin and Lake Superior Regions are becoming densely vegetated but t could be maintained in al suitable state with some intervention. in addition there are several areas of large suitable dune habitat on southern Lake Huron that have no historic record of Pitcher’s Thistle but which are suitable and where introductions could take place if deemed necessary.

- The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Many threats can be avoided or mitigated through communications actions to increase awareness about the species, liaising with other groups and agencies, erecting signage or barriers, working with management of protected areas, working with landowners on stewardship, and many oether steps.

- Recovery techniques exist to achieve the populations and distribution objectives, or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe

Many different techniques are suggested in this strategy and are intended to directly mitigate threats. The diversity of approached ensures that at least some actions will succeed. Since 2005, a .network of volunteers and landowners has conducted annual monitoring of Pitcher’s Thistle in the Manitoulin Region. Data show an increase in numbers .of individuals in most populations. Successful reintroductions have been conducted on Southern Lake Huron and on Lake Superior. At one site on Manitoulin Island, a group of land owners is working together on stewardship, and the resulting monitoring data show a >800% increase in the number of Pitcher’s Thistles.

Executive summary

Pitcher’s Thistle is a whitish-green perennial plant with leaves that are finely divided into narrow segments and spineless except at the tips. The plants live as a ring of basal leaves (a "rosette") for several years before forming an upright flowering stalk and thistle head of pale, pinkish-white flowers. After flowering and setting seed, the plants die. In Canada Pitcher’s Thistle is only found on dunes and beach ridges on the shores of Lake Huron and Lake Superior. Optimal habitat is open, dry, loose sand with little other vegetation. The habitat is dynamic due to sand movement caused by wind, water, and ice actions. There is a balance between the processes that keep sand open and loose, and succession, the natural process that causes a gradual increase in vegetation.

Pitcher’s Thistle is listed as Endangered on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). In Ontario species is listed as Endangered on the Species at Risk in Ontario list under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007). The global range of Pitcher’s Thistle is completely restricted to the shores of Lakes Huron, Michigan and Superior, occurring in four states in the United States and Ontario.

There are 30 extant populations in Canada, all in Ontario; three are on southern Lake Huron, two are on Lake Superior, and the remaining 25 are in Manitoulin Region on Lake Huron. Pitcher’s Thistle has been extirpated from some historic sites on southern Lake Huron. Since 2001 several previously unknown populations of Pitcher’s Thistle were discovered in the Manitoulin Region. At the same time, there have been large increases in numbers of individuals at many known populations in that region. Based on 2008 monitoring data the current total Canadian population is around 55,000 individuals.

Threats to Pitcher’s Thistle are off-road vehicles, browsing; trampling; succession, construction of human structures on beaches, erosion and blow-outs, and competition with invasive species.

The current state of Pitcher’s Thistle populations varies considerably by region. Populations at Pukaskwa National Park are small, with one population appearing healthy and self sustaining, one declining and one population recently extirpated, whereas on Lake Huron, the majority of populations show increases or fluctuations. The populations in the southern Lake Huron region are small, but most seem stable. There is almost no threat of extirpation of the listed species within the next 10 years, although there could be serious losses at the edges of the range. Consequently, the following objectives are designed to ensure the survival of the listed species:

Pukaskwa National Park: Maintain the two existing populations (Oiseau Bay and Hattie Cove) at their current locations. Use the existing populations to restore Pitcher’s Thistle into suitable habitat at a selected site by 2020. Maintain populations at high enough levels that yearly population sizes show natural fluctuations with declines no greater than 30%.

The Manitoulin Region: Maintain the current extent of occurrence, and the largest population of Pitcher’s Thistle in the region on Great Duck Island.

The Southern Lake Huron Regions:Maintain or increase all the existing populations in Inverhuron, Pinery and Port Franks.

Recovery work will involve protection of existing populations, reductions of threats to habitat, and promoting site stewardship, public education, and policy-oriented approaches. Pitcher’s Thistle populations are under several types of ownership or jurisdiction, and First Nations, municipalities, and private landowners will be important partners in recovery work.

Critical habitat is identified in this strategy for populations at Pukaskwa National Park, Pinery and Inverhuron Provincial Parks, Port Franks, and Great Duck Island.

One or more action plans will be completed by 2015

Background

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC

Scientific Name: Cirsium pitcheri (Torr.) T. & G.

Common Name: Pitcher’s Thistle

COSEWIC status: Endangered

Date of Assessment: May, 2000

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

Reason for Designation: An endemic of the Great Lakes shorelines found at only a few sites. It has a very limited area of occurrence with recent population losses and continued risk from low seed set and habitat degradation. It faces additional loss because of recreational use and development of its habitat.

Status history: Designated Threatened in April 1988. Status re-examined and designated Endangered in April 1999. Status re-examined and confirmed in May 2000.

Species Status

Pitcher’s Thistle is listed as Endangered and is on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Pitcher’s Thistle is listed as Endangered on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). In Ontario species is listed as Endangered on the Species at Risk in Ontario list under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007). The global range of Pitcher’s Thistle is completely restricted to the shores of Lakes Huron, Michigan and Superior, occurring in four U.S. states and Ontario. The global rank of Pitcher’s Thistle is Vulnerable (G3) (NatureServe 2010). It is currently listed as Critically Imperilled (S1) in Illinois, Imperilled (S2) in Indiana, Wisconsin, and Ontario, and Vulnerable (S3) in Michigan. The species is federally listed as Threatened in the United States. The species was extirpated in Illinois but has been successfully reintroduced at one site. Some Indiana populations are re-introductions as well. (NatureServe 2010). The Canadian range of Pitcher’s Thistle probably accounts for less than 1/3 of the global geographic distribution.

Description of the species and its needs

Species description

Pitcher’s Thistle is a perennial plant with a distinctive whitish-green colour. It usually appears as a ring of basal leaves (a "rosette") that are finely divided into narrow segments and spineless except at the tips. Rosettes are generally 15-30 cm in diameter.

Pitcher’s Thistle spends the first year as a seedling, and then may spend the next 2 to 11 years as a rosette (Loveless 1984, Stanforth et al. 1997, Maun 1999). At maturity the plants produce an upright stem (~50-100 cm tall) with one to many spiny, urn-shaped thistle heads of many white or pale pink flowers. After pollination, each flower produces a seed-like fruit that may be blown from the plant by wind due to a fluffy attachment that serves as a parachute. After setting seed the plant dies. Pitcher’s Thistle cannot spread vegetatively.

Habitat needs of Pitcher’s Thistle

Dunes, and the biota that inhabit them, are different from most other ecosystems and their biota. They are an exceptionally dynamic and constantly changing ecosystem and the plants and animals that live in them are remarkably mobile. Hence, if we are to protect them, individually or collectively, we must try to protect the whole ecosystem - the complete dune system from lake shore (which itself is constantly changing) to the belt of mature vegetation behind the dunes. We must strive to protect sufficient areas within each location to ensure that the whole ecosystem can continue to flourish, as well as Pitcher’s Thistle within it.

In Canada, Pitcher’s Thistle habitat is only found on sand dunes and beach ridges on the shorelines of Lake Huron, and on two beach ridge sites on Lake Superior. Optimal habitat is open, dry, loose sand with little other vegetation or duff. Pitcher’s Thistle is typically found in Little Bluestem – Long-leaved Reed Grass – Great Lakes Wheat Grass Dune Grassland (Lee et al. 1998, NHIC 2003). It also occasionally occurs in atypical habitats, such as on the upper portion of a relatively steep, gravelly beach, or persisting in fairly dense surrounding herbaceous vegetation (Jones 2001). Greater numbers of Pitcher’s Thistles are usually found in the early-successional foredunes (e.g. nearest the lake), but the species also commonly occurs on backdunes where there are areas of open, loose sand. At large dune sites, Pitcher’s Thistle may be found 100 m or more away from the water. Where a storm event, tree-removal, or tree-fall creates a blowout in a forested dune, the exposed loose sand may be colonized by Pitcher’s Thistle or other rare dune species (Jones 2003).

Normal habitat consists of several distinct zones (Jones 2001-2003; Otfinowski 2002). At the water’s edge there is a hard-packed, wet strand which is bare of vegetation and is unsuitable habitat. Immediately landward of this there is usually a slope or ridge of sand predominantly covered with Marram Grass (Ammophila breviligulata) or Long-leaved Reed Grass (Calamovilfa longifolia var. magna) and little else. There may be a few scattered Pitcher’s Thistle plants here. Inland of this, usually in a trough or a few smaller ridges, is open, loose sand where the majority of thistles are found. From here, moving back towards the forest, the vegetation tends to increase in density, covering the sand more completely, with greater frequency of shrubs. Pitcher’s Thistle may be found in this zone, even as far back as the forest edge, if there are patches of open, loose sand.

Regardless of where in the habitat it occurs, Pitcher’s Thistle can be subjected to extremes of heat, light, drought, wind, and lack of nutrients. As well, it may experience shifts of substrate, sand-blasting, and burial. Otfinowski (2002) found no direct correlation between the amount of Pitcher’s thistle growth and location within the dunes; or with other environmental factors such as moisture or light.

The habitat of Pitcher’s Thistle is dynamic due to sand movement caused by wind, water, and ice actions, and winter storm activities (McEachern 1992). Suitable habitat exists in a balance between the processes that keep sand open and loose, and succession, the natural process that causes a gradual increase in vegetation. Through succession, open areas naturally grow up into forests. In the absence of dynamic processes, sand may become too vegetated for Pitcher’s Thistle.

Biological needs of Pitcher’s Thistle

Pitcher’s Thistle is a monocarpic perennial, meaning it flowers and produces seed only once and then dies. Flowers are bisexual and self-fertile, but self-pollination produces lower rates of seed set than out-crossing (Keddy 1982). A variety of insects visit Pitcher’s Thistle including bumblebees, megachilid bees, anthophorid bees, small and large helictid bees, as well as butterflies, skippers, flies, wasps, honey bees and several types of beetles and true bugs (Keddy and Keddy 1984; Loveless 1984). Pollination is likely not a limiting factor.

The trigger for flowering is still not understood. Rosette size is probably not the main factor since flowering stalks may be produced from rosettes as small as 15 cm in diameter, and non-flowering rosettes as large as 40 cm diameter have been observed (Jones, unpublished data). Pitcher’s Thistle has mycorrhizal fungi associated with its roots (Maun 1999), but it is not known what species are involved or how necessary they are for survival of Pitcher’s Thistle plants.

Pitcher’s Thistle has the largest seeds among thistles in eastern North America (USFWS 2002, Gleason 1952, Montgomery 1977), perhaps to maximize root growth for seedlings in dry sandy habitat (USFWS 2002, Loveless 1984, Hamze and Jolls 2000). Seeds are thought to be viable for up to 3 years (Maun 1999, Rowland and Maun 2001). Studies suggest the quantity of viable seeds may be low (Bowles et al. 1993, Maun et al. 1996). However, when the seed coat was scarified or removed in the laboratory, total germination increased to above 95%, suggesting that seed viability may be high under proper germination conditions, and that a complex dormancy mechanism may be involved (Chen 1997, Chen and Maun 1998). Pitcher’s Thistle appears to have a small year-to-year seed bank (Loveless 1984, Bowles and McBride 1993, McEachern 1992, Hamze and Jolls 2000). Thus, seed dispersal may be more necessary for the stability of Pitcher’s Thistle populations than reliance on seed banks.

Seeds of Pitcher’s Thistle are wind-dispersed, and most fall within 0-4 m of the parent plant (Keddy 1982, USFWS, 2002). In a genetic study of Pitcher’s Thistle in the Manitoulin Region, Coleman (2007a) found identical genotypes at widely separated sites, showing that dispersal over distances of as much as 99 km has occasionally occurred.

Seedling mortality can be related to microhabitat (Keddy 1982). Mortality was shown to be highest in open sand and lowest in debris-covered sand, but there was a trade off between germination and mortality because germination was also highest in open sand areas. Sand erosion contributes to mortality, so dune grasses that stabilize sand and ameliorate the effects of wind and sand blasting may help Pitcher’s Thistle (D'Ulisse and Maun 1996). Delayed maturity also increases the probability of mortality prior to reproduction because rosettes live for a number of years.

Genetic evidence indicates that Pitcher’s Thistle derived directly from Prairie Thistle (Cirsium canescens) through a series of genetic bottlenecks (Loveless and Hamrick 1988) following migration and isolation after glaciation. Pitcher’s Thistle probably dispersed to its present range through sandy habitats formed by Wisconsinan glacial meltwaters (Moore and Frankton 1963, Johnson and Iltis 1963). Studies show Pitcher’s Thistle has a genetic diversity lower than other species of Cirsium (Loveless 1984, Loveless and Hamrick1988). DNA analysis of Pitcher’s Thistle in the Manitoulin and Lake Superior Regions also demonstrated low genetic variability (Coleman 2007a). Six genetically distinct populations were found in the total Canadian population. Despite the possibility of dispersal up to 99 km, this distance is not sufficient to create a meta-population across the Canadian range.

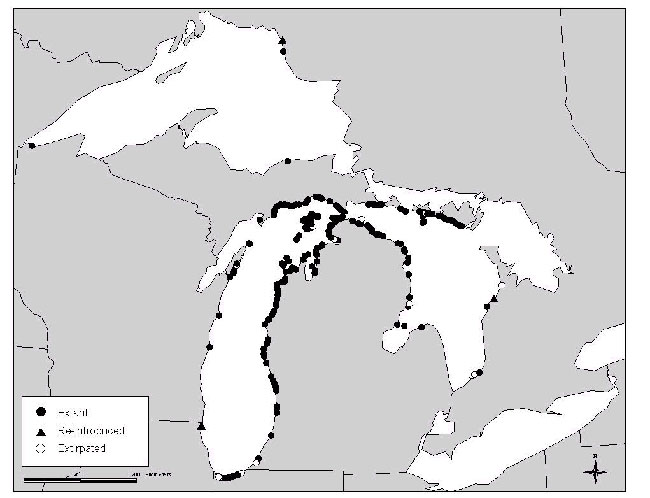

Populations and distribution

The global range of Pitcher’s Thistle is shown in Figure 1. There are 30 extant populations in Canada, all in Ontario. Three populations are on southern Lake Huron, two are on Lake Superior in Pukaskwa National Park, and the remaining 25 are in the Manitoulin Region (on Manitoulin Island, Cockburn Island, and the Duck Islands). The bulk of the global range of the species is in Michigan, where there are approximately 128 sites in 18 counties. There are also 9 sites in Wisconsin and 7 in Indiana (NatureServe 2010). The species was apparently extirpated from Illinois but has been successfully reintroduced at one site. Based on current information (Jones 2009, NatureServe 2010), a cautious estimate would give Canada approximately 15% of the global population if all Canadian occurrences are as big or bigger than U.S. occurrences.

The historic extent of Pitcher’s Thistle in Canada is poorly known. Records show the species once occurred at Sauble Beach in Bruce County and at Kettle Point in Lambton County (Guire and Voss 1963, NHIC 2010), but has been extirpated from both areas. A population at Crescent Beach in Pukaskwa N.P. has not been seen since 2006 and is also presumed extirpated. Pitcher’s Thistle was planted in 1999 at Chantry Dunes, Southampton, Bruce County, a site where the species was not historically known to have occurred. Apparently the reintroduction was unsuccessful as no Pitcher’s Thistle was found in 2002 (Jones 2002). The Middle Beach population at Pukaskwa N.P. (included in the tally of 30 extant populations) is also an artificial introduction, but the species is assumed to be native within the park at Oiseau Bay. The introduction at Hattie Cove has been quite successful, and the population size has increased greatly.

Survey and monitoring work since 2001 has discovered several previously unknown populations of Pitcher’s Thistle in the Manitoulin Region. At the same time, monitoring has documented large increases in numbers of individuals in many known populations in that region. The current total Canadian population is around 55,000 individuals (2008 monitoring data) of which roughly 15,000 were mature plants that died after flowering, leaving approximately 40,000 rosettes in 2009. This calculation did not take into account new seedlings established in 2008 or 2009. Site by site abundance of Pitcher’s Thistle is given in Appendix B.

Figure 1. Global range of Pitcher’s Thistle (sources: Bowles and McBride 1994, NHIC 2009, Jones 2009, NatureServe 2010).

Nearly all major dune sites on Lake Huron have now been searched for Pitcher’s Thistle, so there is little likelihood of finding additional new populations. Jones (2002, 2003a) found no Pitcher’s Thistle at Sauble Beach, at 27 other sites on southern Lake Huron, or at 66 sites on the North Channel (Jones 2006), although much suitable habitat is still present. Many large areas of excellent dune grassland habitat (not occupied by Pitcher’s Thistle) exist on the Lake Huron - Georgian Bay shoreline, and many of these sites support at-risk, rare, or endemic species. Although most of these sites are not known to have supported Pitcher’s Thistle historically, most are thought to be suitable and could support Pitcher’s Thistle if the species should get established there or be introduced. As well, large dunes such as these are subject to the same threats outlined here for Pitcher’s Thistle, so recovery actions developed for this species may also benefit these sites and the associated rare species.

Trends

Monitoring data from 2001 to 2009 show a steady, multi-year increase in overall numbers in 15 populations. Some populations have increased as much as 200-800% while others have had more gentle increases. For 9 populations, multi-year data show natural fluctuations in numbers due to flowering and die-off. Six populations have undergone serious declines due to threats- 5 of these are small populations affected by succession as well as at least one other factor such as browse or ATV use. These populations are: Belanger Bay, Crescent Beach, Christina Bay, Fisher Bay, and Michael’s Bay. The decline at Pinery Provincial Park may be the result of recreational pressure or perhaps from ecological processes (MacKenzie, pers. comm. 2010).

Pitcher’s Thistle clearly has the reproductive capacity to recover and increase in numbers over just a few years, so it remains unclear why numbers of individuals were so low when monitoring began in 2001-2003. It is likely there are longer time-frame cycles of increase and decline that have not yet been observed in their entirety. As well, it is possible that heavy, synchronous flowering and massive die-off (caused by a series of hot, dry years) without concurrent seedling establishment could cause periodic crashes in population numbers (Jones, pers. comm. 2010).

Globally the Little Bluestem – Long-leaved Reed Grass – Great Lakes Wheat Grass Dune Grassland vegetation where Pitcher’s Thistle is found is in decline. It has been given a global conservation rank of G3G5 and thus may be of global conservation concern. In Ontario this vegetation type is ranked Imperilled (S2) (Bakowsky, 1996; NHIC 2010).

Threats

Threat classification

A number of threats affect Pitcher’s Thistle and dune grasslands (Table 1). They derive from both natural and human sources. Presence and severity of threats vary by region and by ownership since dunes in protected areas may experience different usage than dunes on priv ate lands.

During monitoring of Pitcher’s Thistle and its habitat, the threats listed below were assessed at each site using a standardized protocol and specific criteria for each threat (Dune Grasslands Recovery Team 2004).

Table 1: Threats to Pitcher’s Thistle and habitat at individual sites. Severity is ranked as H – High, M – Medium, or L – Low. (Source: monitoring data and observations by recovery team members). A blank box indicates that no evidence of that threat was detectable at the site.

Cockburn Island

Duck Islands

| Threat type | Off-road vehicles | Browse | Trampling | Succession | Human structures | Erosion/ blowouts | Invasive Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desert Point, Great Duck Island | High | ||||||

| Horseshoe Bay, Great Duck Island | Medium | ||||||

| Western Duck Island | High | Medium |

Manitoulin Island

| Threat type | Off-road vehicles | Browse | Trampling | Succession | Human structures | Erosion/ blowouts | Invasive Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belanger Bay | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Burnt Island Harbour | Low | Low | |||||

| Carroll Wood Bay | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | |||

| Carter Bay--main | Medium | Low | Medium | Low | High | High | |

| Christina Bay | High | High | |||||

| Dean’s Bay | Medium | Low | Low | Low | |||

| Dominion Bay | Low | Low | Low | Low | Medium | ||

| East of Black Point | Low | Medium | |||||

| Fisher Bay | High | High | Medium | ||||

| Ivan Point | Medium | ||||||

| Michael’s Bay | Medium | High | Medium | ||||

| Michael’s Peninsula | |||||||

| Misery Bay | Low | Low | Low | ||||

| Portage Bay–East | Medium | High | Low | Low | |||

| Providence Bay | Medium | High | Medium | ||||

| Sand Bay | Medium | High | Low | Low | |||

| Shrigley Bay–East | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | Medium | ||

| Shrigley Bay–West | High | High | Low | Medium | High | ||

| Square Bay | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Taskerville | |||||||

| Timber Bay | Medium | Low | High | Low | Medium |

| Threat type | Off-road vehicles | Browse | Trampling | Succession | Human structures | Erosion/ blowouts | Invasive Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inverhuron PP | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Low | Low | Medium |

| Pinery PP | Low | High | Medium | Low | |||

| Port Franks | High | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium | |

| Pukaskwa National Park | High | Medium | High |

Description of threats

- Off-road vehicles: Off-road vehicle use is a serious concern, especially as all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) are nearly unrestricted in their movements and do not require trails or roads. ATVs disturb or destroy vegetation, displacing the grasses and shrubs that stabilize sand and allowing erosion and blow-outs. They are also vectors for weeds. Because ATV use is an increasingly popular recreational pastime, the threat is widespread. Damage to habitat from ATVs is prevalent on Manitoulin Island especially where shoreline areas contain a public right-of-way.

- Browse: Pitcher’s Thistle is subject to browsing by White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus), the Plume Moth (family Pterophoridae), rabbits, and Canada Geese (Branta canadensis). Leaves in the rosette stage may be eaten as well as the young flowering heads. In some cases, browsing can be so severe that only the small central nub of the plant remains. Browsing may contribute to over- wintering mortality by reducing the quantity of energy being stored in reserve. Browsing has contributed to a drastic crash in the population at Western Duck Island, and is an especially serious issue where it is combined with other threats such as in very small populations with marginal habitat (Jones 2009).

Browsing is considered a threat, rather than a natural limitation because the effect can be very serious and the high number and densities of browsers is not natural where Pitcher’s Thistle occurs. The deer population on Manitoulin Island peaked in 2003 at a level higher than the carrying capacity of their habitat. Numbers were reduced in the last few years by increasing the number of tags issued to hunters (Wayne Selinger, pers. comm). Browsing by deer continues to be a problem observed during monitoring. The huge population explosion of Canada Geese in recent years contributes to the problem. The results of heavy browsing seriously threaten the continued survival of Pitcher’s Thistle at several sites.

- Trampling by pedestrians: High visitor use and the resulting foot traffic, especially in protected areas, can damage vegetation and remove stabilizing grasses and shrubs. Foot traffic creates paths through dunes that then encourage more pedestrian use causing further increases in the severity of this threat.

In recent years, this threat has been addressed at Inverhuron Provincial Park, Pinery Provincial Park, Providence Bay, and Carter Bay by constructing boardwalks, stairways, or designated pathways through dunes to keep pedestrians off the vegetation. The severity of trampling, although still a concern, is now somewhat reduced at Inverhuron Provincial Park, Providence Bay, and Carter Bay. At Pinery Provincial Park, this threat remains a concern and may be one factor in the continuing decline of the population there. At Pukaskwa National Park, trampling has been reduced at Hattie Cove by cordoning off the Pitcher’s Thistle population with a railing.

- Succession: Pitcher’s Thistle requires some level of natural environmental disturbance to keep sand open, loose, and sparsely-vegetated. In natural dune ecosystems, the actions of wind, wave-wash, and storms accomplish this, counteracting the natural trend for land to grow up with shrubs and trees. However, in the absence of natural dune processes, sand may become too vegetated for dispersal, germination, and establishment of Pitcher’s Thistle seedlings (although rosettes may survive for a number of years in heavy vegetation). Low water levels in Lake Huron have moved the wave-wash zone away from the foredune, allowing heavy growth of vegetation to occur at some sites.

- Human structures: This threat encompasses both new construction on dunes and the presence of existing structures that change or prevent dune processes. Most sandy bays on Manitoulin Island are subdivided and have cottages present in the back dune or forest. Some landowners have placed fire pits, volleyball courts, boat storage, decks or stone patios, or even fill dirt and grass lawns on dunes. Depending on how they are constructed and the intensity of use, these structures may damage or destroy Pitcher’s Thistle and areas of habitat. Human structures on dunes remain an on-going issue.

Shoreline development itself may destroy dune habitat; however, in many cases development occurs in the adjacent forest directly behind dunes rather than on the dunes themselves. Maintaining an adequate set-back distance from active dunes during development planning can reduce impacts to Pitcher’s Thistle habitat and allow dune processes to continue. However, the aftermath of shoreline development has generally resulted in increased human use of dunes which has increased the incidence of other threats discussed in this section.

- Erosion and blow-outs: Areas of open, loose sand are beneficial to Pitcher’s Thistle, but actively eroding or suddenly shifting sand can mean a loss of plants and beneficial substrate as well as the potential of mortality from burial. Once an area begins to erode or blow out, there tends to be a sequential effect as the hole becomes bigger and bigger allowing more and more sand to blow and the effect to increase in severity. Erosion and blow-outs are more often the result of human activities although they occasionally occur naturally. Newly exposed sand may later be re-colonized by Pitcher’s Thistle, but the net result of this threat is usually a loss of large areas of stabilized vegetation and a loss of thistles.

- Invasive species: Any species that spreads rapidly and takes over habitat to the exclusion of native species may be a threat on dunes. On southern Lake Huron, the invasive race of the Common Reed (Phragmites australis) has taken over huge areas of shoreline, eliminating the natural vegetation. So far, Pitcher’s Thistle populations in the southern Lake Huron region remain unaffected, although the Port Franks site has other invasives present. However, monitoring has now picked up the presence of invasive Common Reed at several sites on Manitoulin. At Pukaskwa National Park, one site is becoming heavily overgrown with Silver-berry (Elaeagnus commutata) following a major natural disturbance. While this is a native species, it appears to have the ability to spread rapidly and reproduce heavily, and it is reducing habitat quality for Pitcher’s Thistle there.

Potential threats

- Genetic isolation of small populations: Coleman (2007a) examined genetic diversity among Pitcher’s Thistle populations and found the species had a low genetic diversity with heterozygote deficiencies within nearly all populations. This confirms earlier studies (Loveless 1984, Loveless and Hamrick 1988) showing that Pitcher’s Thistle has a genetic diversity lower than other species of the genus Cirsium. Pitcher’s Thistle is restricted to a very specific habitat within just the Great Lakes region. If a change in conditions or a disease were to occur, it is unknown whether the species would have the genetic diversity to adapt to a new situation. As well, the effects of small populations (fewer than 50 individuals) are many. With a monocarpic life strategy the plants do not flower every year, and with few individuals there is decreased likelihood of outcrossing because only a few plants may flower at the same time. The distribution of Pitcher’s Thistle range-wide consists of many widely separated populations, several of which contain fewer than 50 individuals. These small populations face greater risk of extirpation. Lack of connectivity and genetic interchange between populations may limit Pitcher’s Thistle recovery. Even within geographic regions, populations are separated by hundreds of kilometres. Large tracts of suitable habitat are no longer present between current populations, due to development and recreational uses. The effects of this potential threat needs further study.

- Changes in lake levels: Flooding, wave-wash, and ice-scour are dynamic processes vital in maintaining the habitat of Pitcher’s Thistle. The recent period of low water level in Lake Huron greatly increased the distance between the wave-wash zone and the dunes, removing active processes from the area where Pitcher’s Thistle is found. This has resulted in a great increase in successional vegetation cover, with the habitat becoming nearly unsuitable at several sites. Historically, this has probably been one of the natural limitations on Pitcher’s Thistle. However, with human controlled out- flow rates in the Great Lakes (Derecki 1985) and potential diversion of water from Lakes Huron and Michigan, it is not certain that the natural lake level cycles will continue.

- Changes in climate: Changes in temperature and rainfall patterns may affect Pitcher’s Thistle. Monitoring data showed a great increase in the percentage of plants that flowered in 2006 and 2007, years which were exceptionally dry and hot. Drought has also been observed as a major cause of mortality in seedlings (McEachern 1992, D'Ulisse 1995, D'Ulisse and Maun 1996, Jones 2001, Weller pers. comm. in USFWS 2002). Since plants of Pitcher’s Thistle die after flowering, any factor that changes the proportion of maturing plants may affect the overall population.

Recovery of Pitcher’s Thistle

Population and distribution objectives

It is likely that there is long-term variation in numbers of Pitcher’s Thistle, and that monitoring has not yet documented this. However, short term fluctuations from flowering and die-off are well known. Therefore, the potential for much larger variation must be incorporated when setting out recovery objectives for Pitcher’s Thistle. The most recent assessment of Pitcher’s Thistle conducted for COSEWIC in 2009 (Jones) determined that the overall trend for the species has been an increase in the number of individuals across the total population, but with a decline in 5 of the 30 populations.

The current state of Pitcher’s Thistle populations varies considerably by region. Populations at Pukaskwa National Park are small, with one population appearing healthy and self sustaining, one declining and one population recently extirpated; whereas in the Manitoulin Region, the majority of populations show increases or fluctuations. The populations in the southern Lake Huron region are small, but most seem stable. There is almost no threat of extirpation of the listed species within the next 10 years, although there could be serious losses at the edges of the range. Consequently, the following objectives are designed to ensure the survival of the listed species:

Pukaskwa National Park:Maintain the two existing populations (Oiseau Bay and Hattie Cove) at their current locations. Use the existing populations to restore Pitcher’s Thistle into suitable habitat at one new site by 2020. Maintain populations at high enough levels that yearly population sizes show natural fluctuations with declines no greater than 30%.

The Manitoulin Region:Maintain the current extent of occurrence, and the largest population of Pitcher’s Thistle in the region on Great Duck Island.

The Southern Lake Huron Region: Maintain all the existing populations, and the extent of suitable habitat, in Inverhuron Provincial Park, Pinery Provincial Park and Port Franks.

Actions already completed or underway

The following recovery actions have been completed or are currently underway:

- Field surveys have been done of all known Pitcher’s Thistle sites and most non-Pitcher’s Thistle dune sites and potential habitat on the southern Lake Huron coast and the North Channel (Jones 2001-6).

- A standardized monitoring procedure is in place for populations and habitat range-wide. All sites range- wide were monitored in 2008 and most were monitored in 2009. A network of trained volunteers has monitored some sites on Manitoulin Island since 2004 (Jones 2005b).

- Contact is on-going with the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point (Ipperwash) First Nation for inventory purposes (2001), to provide a draft of the recovery strategy (2006), and to share information.

- Initial contact has been made between OMNR and Manitoulin municipalities with Pitcher’s Thistle occurrences (2005).

- A genetics study of Manitoulin and Pukaskwa Pitcher’s Thistle populations has been done (Coleman 2007a & b).

- A resource management plan is in place for Pinery P.P. (OMNR 1989) and vegetation management plans are in place for Pukaskwa N.P. (Lopoukhine 1989) and Inverhuron Provincial Park (OMNR 2008).

- Pitcher’s Thistle was introduced at Middle Beach, Pukaskwa N.P. (1991).

- A draft communications strategy has been developed (Parks Canada 2006).

- Pitcher’s Thistle brochure was published for Pukaskwa N.P. (Pukaskwa National Park 2003).

- A dune grasslands web site was developed by the recovery team and is on-line (2006).

- Dune conservation signage was installed at Sauble Beach and Dominion Bay (Manitoulin Island); other Habitat Stewardship Program-funded activities are ongoing at southern Lake Huron dune sites.

- Pitcher’s Thistle and Species-At-Risk poster was created by the recovery team and distributed to 14 key locations for outreach (2007).

- A Cottage Image Plan (a guide to low impact landscaping for dune landowners) was completed (2007) and distributed (2008).

- Preliminary inventory work on invertebrates was undertaken, identifying some significant species (H. Goulet, pers. comm.) (2001 to present).

- Dune displays were created by the recovery team are in place at major information centres on Manitoulin Island, at Tobermory, and on the Chicheemaun ferry (2008).

- Publications for municipalities, dune users, and people who live in or near dunes have been prepared (Peach 2005; Leal et al 2006).

- A dunes video and a dunes brochure for a general audience are near completion.

Approaches recommended to meet recovery objectives

Outlined below are the possible approaches that will have to be undertaken in concert with volunteers, interested groups, and other cooperating agencies.

Table 2. Approaches to meet recovery objectives

| Priority | Strategies | Threats addressed | Recommended approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | Habitat protection – coordination of recovery activities | Trampling; off road vehicles; human structures | Develop a list of priority sites for habitat protection and management based on threat assessments (Table 1) |

| Urgent | Explore methods to control invasive species in dune systems | Invasive species | Determine if control can be undertaken before infestation is widespread |

| Necessary | Protection of existing populations | Trampling; off road vehicles; human structures | Protected areas will be managed to reduce the impact of threats. |

| Necessary | Habitat protection through legal enforcement | Trampling; off road vehicles | Work with Conservation Officers and Bylaw Control Officers to identify situations that require increased enforcement and monitoring of compliance |

| Necessary | Study genetics of southern Lake Huron populations | Small populations | Indicate degree of genetic isolation; determine appropriate historic distribution of species. Evaluate whether to augment or reintroduce Pitcher’s Thistle on southern Lake Huron |

| Necessary | Promoting site stewardship | Human structures; trampling; off road vehicles | On private lands encourage landowners to take a stewardship interest in their property. Actions can include posting signage and designating specific trails to reduce damage by pedestrians and vehicles. Provide recognition packages and stewardship awards to private land stewards. Outside protected areas tools include conservation easements, and linking landowners with funding for habitat protection work. |

| Necessary | Protection of existing populations | Small Populations | Monitor at sites where populations are in decline to determine by 2020 if these populations have continued to decline, or are increasing, stable, or fluctuating in numbers. |

| Necessary | Habitat protection –municipal planning; education and communications | All | Provide policy, stewardship and management information to municipalities and planning agencies. During the Manitoulin Official Plan update, there is an opportunity to support the designation of some sites as ANSIs, which would provide these sites some additional protection under the Ontario Provincial Policy Statement |

| Beneficial | Habitat protection –management and stewardship | Human structures; trampling; off road vehicles | Provide information on financial incentives to landowners for increased protection of dune habitat Identify sites eligible for special programs or designations e.g. Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI), Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program (CLTIP). Habitat Stewardship Program (HSP) Ecological Gifts Program. |

| Beneficial | Compile existing information on dune processes at selected sites | Small populations | Identify landscape-scale threats to dune systems |

| Beneficial | Habitat modification to suit Pitcher’s Thistle | Succession | The need for human intervention for habitat improvement should be evaluated, and implemented if required. |

| Beneficial | Conduct population viability analyses (PVAs) | Small populations | Model long term viability of Pitcher’s Thistle populations and compare management alternatives |

| Beneficial | Population enhancement or restoration | Small populations | Research methods to reintroduce or augment Pitcher’s Thistle populations; reintroduce or augment Pitcher’s Thistle populations at suitable degraded or historic sites if necessary |

| Beneficial | Communications and outreach | All | Targeted communications to engage the public in valuing and protecting Pitcher’s Thistle and about conscientious use of dune habitats. Cooperate with local partners, such as local stewardship councils, fish and game clubs, etc., to promote awareness and protection of publicly accessible dunes, |

Critical habitat

Critical habitat is defined in the Species at Risk Act (2002) section 2(1) as ―the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species' critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in the action plan for the species. In a recovery strategy, critical habitat is identified to the extent possible, using the best available information. Ultimately, sufficient critical habitat will be identified to completely support the population and distribution objectives.

In the section below, nine parcels of critical habitat are identified for Pitcher’s thistle at seven sites throughout its Canadian range. This represents a significant contribution to achieving the objectives; however, additional critical habitat will be needed. Recent surveys funded by the Species at Risk Program discovered far more populations of Pitcher’s Thistle than expected. At this time, we do not have adequate information to determine which of those populations should be identified as critical habitat to achieve the objectives. A schedule of studies, which outlines the work required to complete the identification of critical habitat, is included below. In the meantime, implementation of the broad strategies and approaches outlined will aid in meeting the population and distribution objectives.

The critical habitat thus identified represents a significant contribution to the recovery objectives, and other recovery tools will be used to fulfill the objectives as outlined in the Broad Strategies and Approaches section.

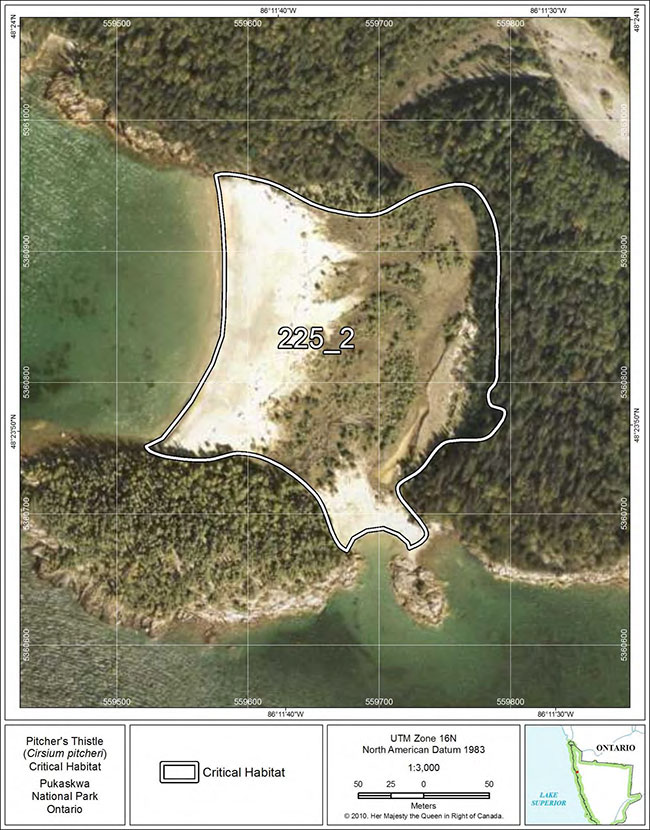

Information used to identify critical habitat locations and attributes

Critical habitat was mapped by Parks Canada in cooperation with Ontario Parks and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources in April of 2010. Mapping was based on coordinates taken in the field during monitoring. The data available varied by site. Three sites had points for habitat boundaries; two sites had coordinates for individual plants; one site had partial coordinates for plants and boundaries, and one site had only a location point in the center of the habitat. Coordinates were plotted on Quickbird imagery (6 satellite images at 60 centimetre resolution with a date range of June 2005 – August 2008). Critical habitat polygons were drawn based on the rules outlined for detecting substrate changes and forest cover. The 15m distance into the trees at the inland boundary was plotted by the GIS software from a line identified on the imagery as the end of the open dune.

Within dunes, Pitcher’s Thistle habitat consists of a series of different vegetation zones, more or less parallel to the water’s edge, starting at the lake and running inland towards the forest. Pitcher’s Thistle is normally not found right along the water’s edge in the active wet strand. The amount of vegetation present in these zones changes gradually from open, loose, nearly-bare sand near the water, to sand covered with patches of low shrubs and trees further inland. Pitcher’s Thistle may occur in all of these zones.

The front boundary of critical habitat varies, and can start at the wet beach area, although this varies depending on the type of frontal beach (see Figures 3 to 10). The lateral boundaries of critical habitat are a very obvious change from open sand to soil, bedrock, gravel, or cobbles where dune processes don't occur because there is no sand. Because the change from dunes to other substrate is usually quite abrupt at the lateral boundaries, a transition zone is often not required in this part of the critical habitat. Occasionally in areas of very large habitats that are occupied by Pitcher’s Thistle in only a small area, critical habitat boundaries have been drawn to allow sufficient room for dispersal and colonization of new areas. The critical habitat boundary then includes the next nearest adjacent area suitable for habitat dispersal.

Almost all Pitcher’s Thistle sites are bordered by forest or woodland behind the dunes. The distance critical habitat extends from the back edge of the open dune into the trees depends on tree type and morphology, stand density, and other variables determined by experts in the field. For the purpose of critical habitat, a distance of 15 metres inland of the point where trees begin to cover 60% or more of the ground is critical habitat.

Pitcher’s Thistle habitat is dynamic, with shifting substrate and changing vegetation cover. As a result, the area required for critical habitat may also change, so it is suggested that the appropriateness of the boundaries of critical habitat be re-evaluated on a 10-year cycle, which would also correspond to COSEWIC's assessment cycle.

Critical habitat identification

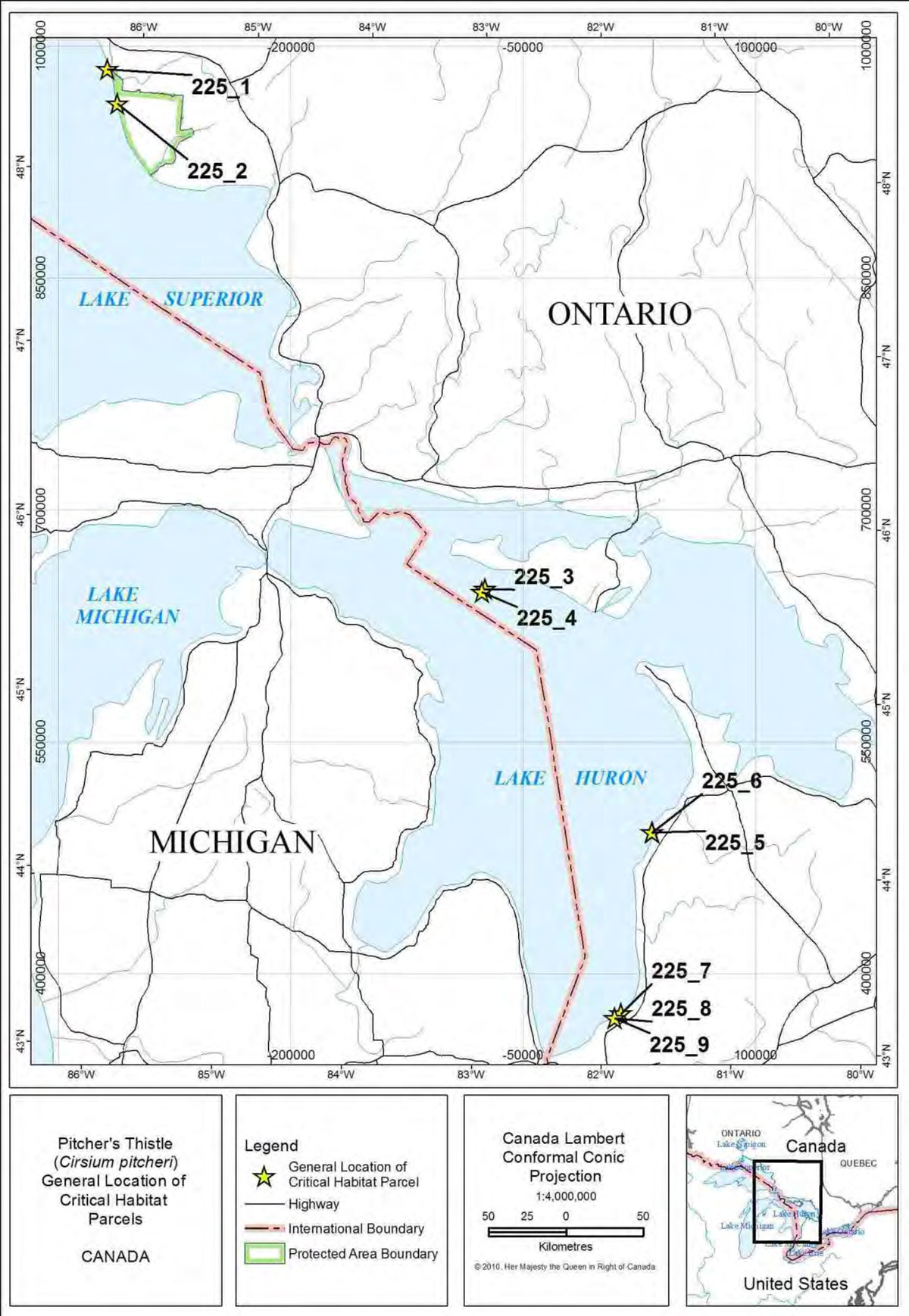

The 9 critical sites parcels have been identified as follows. They are shown on the locator map (Figure 2), and in more detail in the maps that follow (Figures 3 - 10)

Figure 2. Locator map for the critical habitat in Ontario

Enlarge Figure 2. Locator map for the critical habitat in Ontario

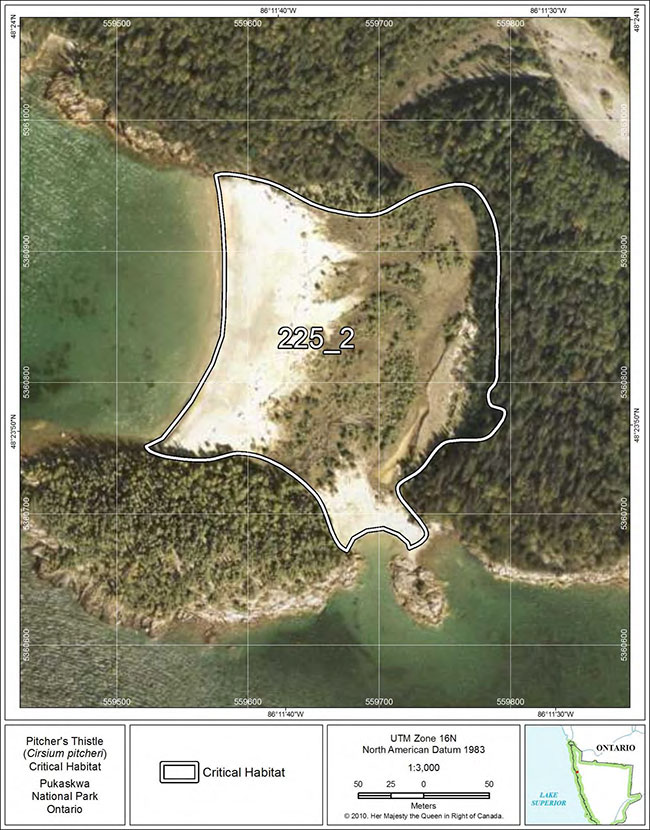

Figure 3. Pukaskwa National Park: Hattie Cove, Middle Beach

Figure 4. Pukaskwa National Park: Oiseau Bay, Creek Beach

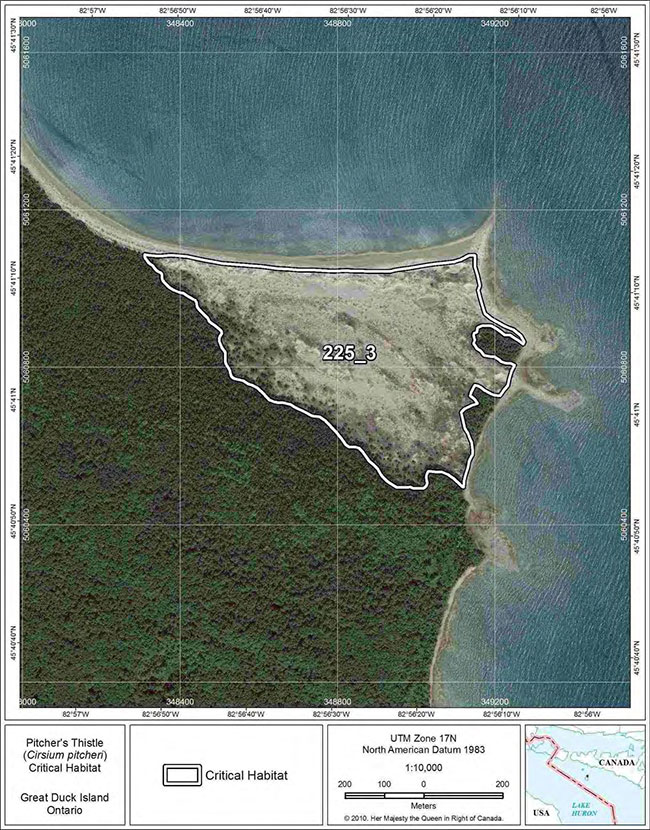

Figure 5. Manitoulin Island Region: Great Duck Island, Desert Point

Enlarge Figure 5. Manitoulin Island Region: Great Duck Island, Desert Point

Figure 6. Manitoulin Island Region: Great Duck Island, Horseshoe Bay

Enlarge Figure 6. Manitoulin Island Region: Great Duck Island, Horseshoe Bay

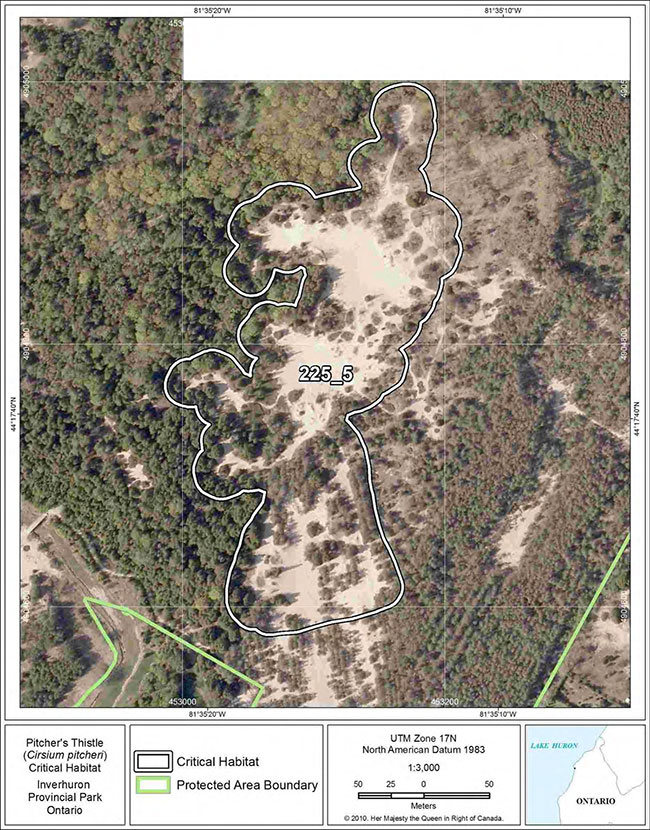

Figure 7. Southern Lake Huron Region: lnverhuron Provincial Park: Back dune area

Enlarge Figure 7. Southern Lake Huron Region: lnverhuron Provincial Park: Back dune area

Note: The term "Protected Area" used in the critical habitat maps has no relation to protection requirements under SARA

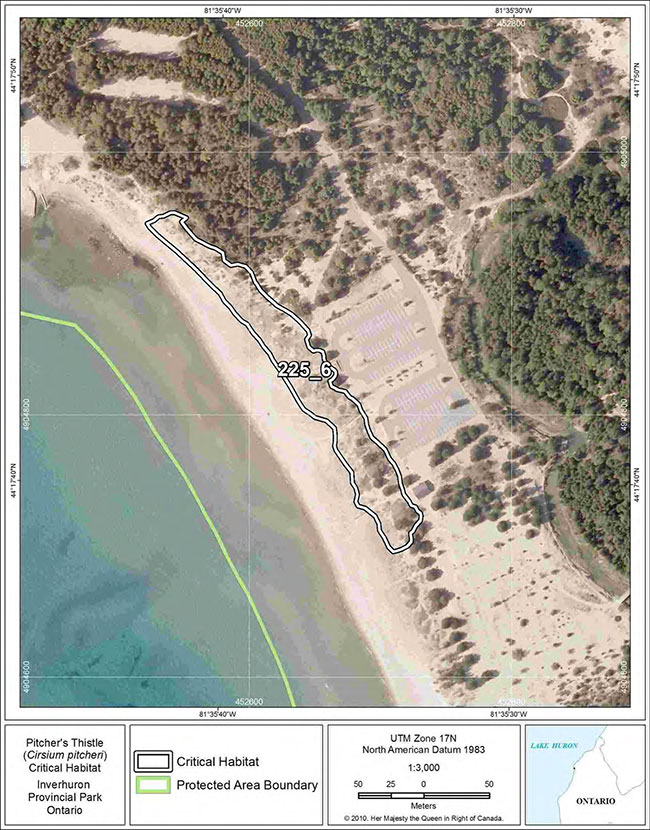

Figure 8. Southern Lake Huron Region: lnverhuron Provincial Park: North population

Enlarge Figure 8. Southern Lake Huron Region: lnverhuron Provincial Park: North population

Note: The term "Protected Area" used in the critical habitat maps has no relation to protection requirements under SARA

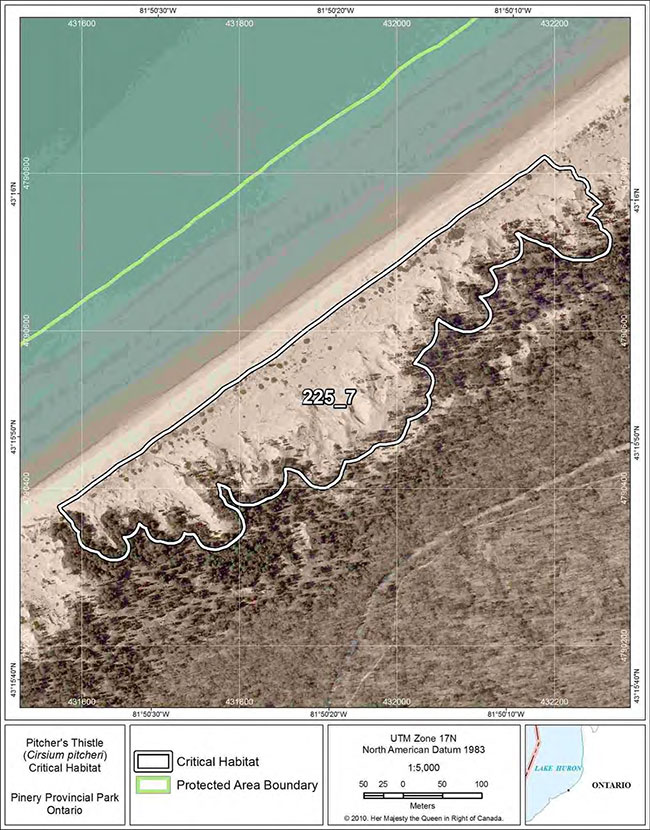

Figure 9. Southern Lake Huron Region: Pinery Provincial Park: Front dune area

Enlarge Figure 9. Southern Lake Huron Region: Pinery Provincial Park: Front dune area

Note: The term "Protected Area" used in the critical habitat maps has no relation to protection requirements under SARA

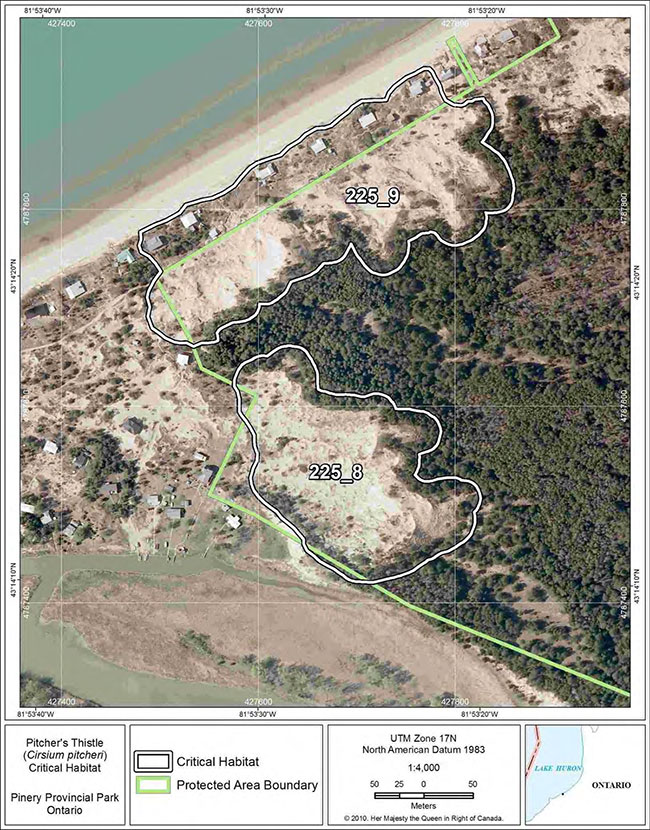

Figure 10. Southern Lake Huron Region: Pinery Provincial Park: South populations

Enlarge Figure 10. Southern Lake Huron Region: Pinery Provincial Park: South populations

Note: The term "Protected Area" used in the critical habitat maps has no relation to protection requirements under SARA

GIS shape files of all the critical habitat parcels are maintained by Parks Canada. The rationale for the boundaries at each site is detailed in a separate document on file with Parks Canada, Species at Risk Section, Ottawa (Parks Canada 2010).

Activities likely to destroy critical habitat

- Activities that disrupt or destroy stabilizing vegetation leading to erosion, blow-outs, and burial;

- Vehicle, ATV, and snowmobile use on dunes and upper beach portions of critical habitat outside of designated right-of-ways with existing infrastructure;

- Trampling, cutting or removal of native dune grassland vegetation;

- Random camping within critical habitat;

- Use of heavy equipment anywhere in the critical habitat;

- Sand mining, sand removal, and bulldozing sand;

- Raking or "cleaning" the beach of vegetation.

- Activities that reduce native species presence and introduce exotic species, leading to degradation of habitat suitability for Pitcher’s Thistle:

- Bringing in fill or topsoil;

- Seeding lawns or planting non-native species;

- Planting trees;

- Grazing by livestock.

- Activities that change dynamic dune processes, which may disrupt wave action, negatively alter natural sand deposition patterns, or disrupt the flow of littoral sediments:

- Construction of groynes, seawalls, revetments or other fixed structures where critical habitat includes near-shore areas;

- Construction or placing of structures e.g., houses, cottages, saunas, garages or sheds, driveways, hard surfaces, temporary docking facilities, etc.;

- Construction of boardwalks or use of snow fences;

- Building roads across dunes.