4. Managing disposal of heritage places of worship

It is always a difficult decision, but not unusual in a rapidly changing and evolving society, to declare a heritage place of worship redundant. Changes in demographic forces and the religious needs of faith groups may require consolidation of multiple places of worship or moving to a new expanded facility in order to allow the faith to continue to serve its members.

Few congregations are structured to, or capable of, financing the long-term conservation of a property that they no longer use. Some owners of multiple heritage places of worship are faced with making difficult decisions about disposing of properties no longer in active use. Disposal of a property can be a means of funding the conservation of other heritage places of worship.

When the heritage property is no longer viable as an active place of worship, the method of its disposal must be carefully considered to protect its cultural heritage value or interest. Having a conservation plan helps determine the most strategic approach to disposal. It is important to engage with the community when developing a policy or strategy for disposal, as the heritage place of worship remains a part of the community’s heritage.

Many former heritage places of worship, such as The Church Lofts on Dovercourt Road in Toronto, have been adapted successfully to new uses, giving them a continuing role in the life in the community. It is important that the new use is compatible with the heritage place of worship’s cultural heritage value, to ensure its ongoing conservation.

4.1. Deconsecration and removal of liturgical elements

When a congregation or faith group relocates from a designated heritage place of worship to another building there is often a wish to relocate liturgical elements of the building that are intrinsic to worship. If the elements are included as heritage attributes in the designation bylaw, their removal would require municipal approval. In this circumstance, the objectives of heritage conservation and protection should be considered along with the religious needs of the faith group on a case-by-case basis.

4.2. Sale for adaptive reuse

A common option for disposal of an unused heritage place of worship is to sell it. Redundant heritage places of worship are often attractive properties for reuse, either continuing as a place of worship or adapted to a new use. From a heritage conservation point of view, the sale of a property in “as is” condition is preferred to mothballing, relocation or demolition.

Reusing heritage buildings instead of demolishing them is also considered to be better for the environment as it reduces waste of energy and materials.

Ideally, a potential purchaser’s proposed new use will suit the existing building and avoid impacting its heritage attributes.

There are many examples in Ontario of successful adaptive reuse of a heritage place of worship in its original location, undertaken with sensitivity to its heritage attributes. In addition to the examples in this guide, the Ontario Heritage Trust’s Places of Worship Inventory contains detailed case studies showcasing a wide range of adaptive reuses.

4.3. Mothballing

Where a heritage place of worship is unoccupied but no alternative use has been found, and options for disposal are being considered, there is still a responsibility to maintain the heritage place of worship at a minimal level to avoid loss of its cultural heritage value or interest. This is often called “mothballing”. In this case, the property is stabilized to prevent deterioration and secured against damage from weather, pests, animals or vandals, and regularly monitored and repaired as necessary. This helps protect its heritage attributes and economic value for future use.

The municipality can enforce building standards to ensure the property is not subject to “demolition by neglect”, potentially posing a public health and safety hazard.

4.4. Relocation

Relocation may be considered when a heritage place of worship’s heritage attributes would be threatened in its original location. An example would be a proposed road widening or similar public municipal infrastructure project extending into the area of the building itself. If the goal of relocation is to upgrade or provide new facilities, other design options that leave the building in its original position should be considered.

Where it has been determined that a heritage place of worship cannot be retained in place, the first option should be relocation or reorientation on its original site. Relocation off site should be considered only after all options have been fully explored.

If the heritage place of worship is designated under the Ontario Heritage Act, relocation is considered “removal”. The property owner must follow the same approval process as a request for demolition when seeking approval to relocate a designated heritage place of worship. If relocation is approved, council must repeal the designation bylaw on the original property and may consider passing a new bylaw designating the property to which the building has been relocated. Ontario Regulation 385/21 under the Ontario Heritage Act provides municipalities with the option of following a modified and expedited designation process as part of a demolition / removal application process where a building or structure from a previously designated property is relocated to a new property and it is determined that the new property meets the criteria for determining cultural heritage value or interest under Ontario Regulation 9/06. Further details on steps a municipality can and must take following consent to removal of a building or structure on a designated property can be found in the Designating Heritage Properties guide.

If relocation from the original site is determined to be the only option, the new location should be chosen with the heritage attributes of the building in mind.

Figures 24 and 25. Victoria Square Wesleyan Methodist Church in Markham is a modest 165-year-old wooden frame building which served as a place of worship until 1880, when it was replaced by a larger brick Gothic Revival Church. The building was moved off site and converted to a blacksmith’s shop. In 2003, the Victoria Square United Church rallied to purchase the vacant and badly damaged structure. The original wooden chapel was moved back to the church property and lovingly restored. (Image courtesy of the City of Markham).

4.5. Demolition of a heritage place of worship

In the Ontario Heritage Tool Kit

Details about the municipal process for demolition of designated properties can be found in Designating Heritage Properties: A Guide to Municipal Designation of Individual Properties under the Ontario Heritage Act.

As a community heritage asset, the demolition of a heritage place of worship should be considered only as a last resort after options that do not involve demolition have been fully explored (for example, mothballing, sale for adaptive reuse, relocation, retention or partial retention in a new building).

Property owners may need to consider full or partial demolition when the structure of a heritage place of worship is determined to be unstable or unsafe and beyond repair (for example, as a result of a fire). In these cases, before making the decision to demolish, the property owner should have an analysis of the structure done by a qualified structural engineer with experience in conservation of historic structures to determine whether the damage can be repaired.

Heritage places of worship protected under the Ontario Heritage Act (for example, listed on the municipal register, designated or with a heritage conservation easement) must follow the demolition permitting process as set out in the Act, as well as any processes specific to the municipality. Proposed demolitions or removal of structures on designated properties require written consent from the municipal council. The property owner may appeal council decisions about demolition to the Ontario Land Tribunal.

If demolition goes ahead, it is important to complete a full record of the existing building. Measured drawings and photographs are the best means to capture the overall structure and property, along with expert recording of as much information as possible on the history, manufacture, placement and detailed description of the heritage attributes. When the property is protected under the Ontario Heritage Act, a best practice is to file this report with the municipality as a record of the property. In the absence of other conservation options, a good practice may be to consider if and how a property's heritage attributes can be salvaged. This could include repurposing or relocation.

The property owner may wish to erect a commemorative plaque, monument, or didactic panel to acknowledge the former historic structure and the property’s heritage.

Case study 4: Rydal Bank United Church, Township of Plummer Additional — Adaptive Reuse of a Heritage Place of Worship

Designated in 2006 under the Ontario Heritage Act.

Rydal Bank United Church is a heritage place of worship that has been successfully adapted for reuse in its original location. The Carpenter’s Gothic style church was constructed in 1907-08 to service the bustling northern farming and mining community. Built on a stone foundation containing “puddingstone” (a local conglomerate rock), the simple wooden church features a steeple, decorative wood shingles, and pierced board gable trim. The church is an important symbol of the town’s rich history — at one time Rydal Bank boasted two hotels, a general store, a sawmill, and three churches. When the church was closed in 1978 community members feared that the local landmark would be torn down or allowed to decay; they had already seen other community churches dismantled and moved.

Over the next 10 years, community members worked to ensure that the building did not deteriorate. They carefully preserved the wooden exterior, stained glass windows, and the natural wood paneling of the interior. The Rydal Bank Historical Society was formed in 1987 in an effort to find a new use for the church. The historical society purchased the church in 1989. Its dedicated volunteers now maintain it as a ‘living museum’ and promote the history of the church and Rydal Bank through open houses, museum displays, and educational tours.

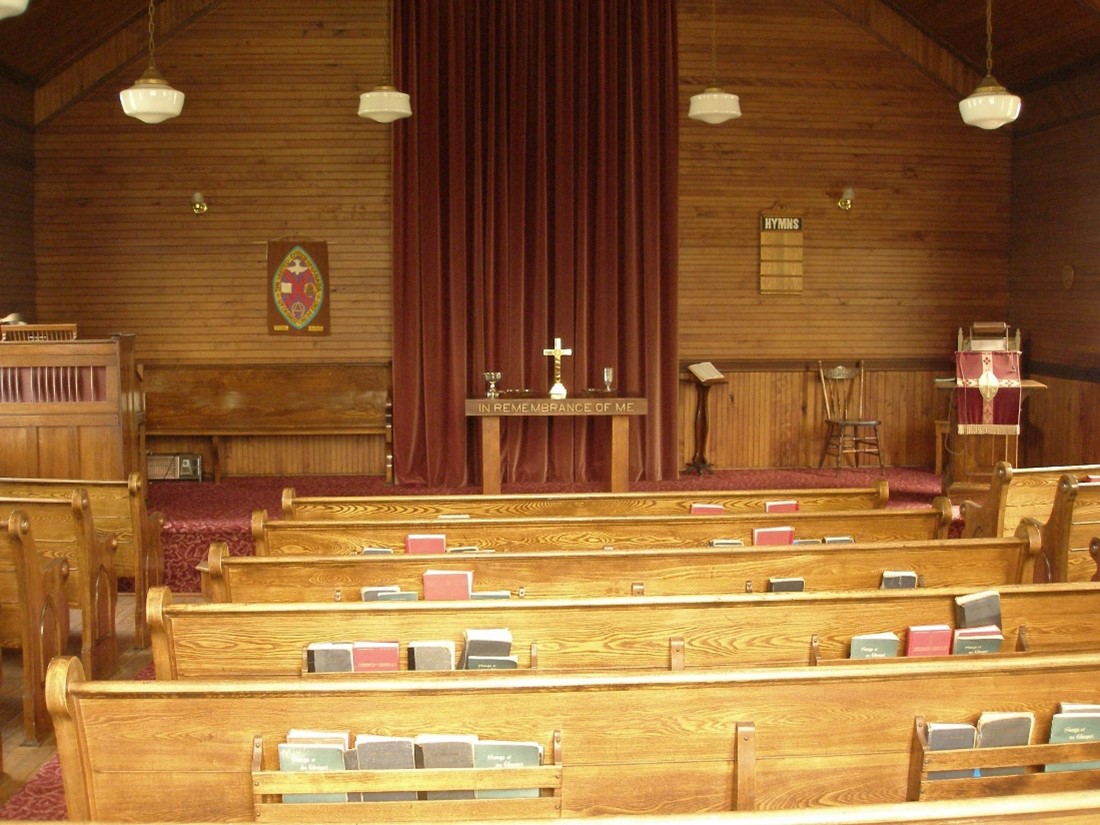

In 2006, the historical society initiated designation of the property under the Ontario Heritage Act in order to ensure the church’s continued protection. This was the first heritage designation in Plummer Additional. Using the Ontario Heritage Tool Kit for reference, the historical society walked municipal staff and council through the designation process and requirements. With the support of the municipality and the assistance of an architect based in Sault Ste. Marie, the historical society carefully drafted a bylaw that would protect the stained glass windows and interior heritage attributes — the white globe lamps, wooden pews, communion table, pump organ and pulpit — as well as the wooden exterior. By doing much of the legwork for the small municipal staff, the historical society made the designation process easy and appealing.

Rydal Bank is a small community of only 23 families, yet the historical society has managed to raise significant funding to restore and maintain the building. To mark the 100th anniversary of the church in 2008, the group raised over $30,000 (including a grant from the Ontario Trillium Foundation) to restore the stained glass windows. The historical society continues to fundraise through special events and an annual community Thanksgiving dinner. The successful adaptive reuse and conservation of this local landmark by a small, rural community is due to the hard work of the historical society, continued community support, and the cooperation of the various parties during disposal.

Points to note

- Creative adaptive reuse was the result of grassroots volunteer activity in a small rural community.

- The heritage place of worship was mothballed and carefully maintained for an extended period until a new use was found.

- There was successful long-term cooperation and collaboration between the property owner and municipality before and after the adaptive reuse.