Introduction

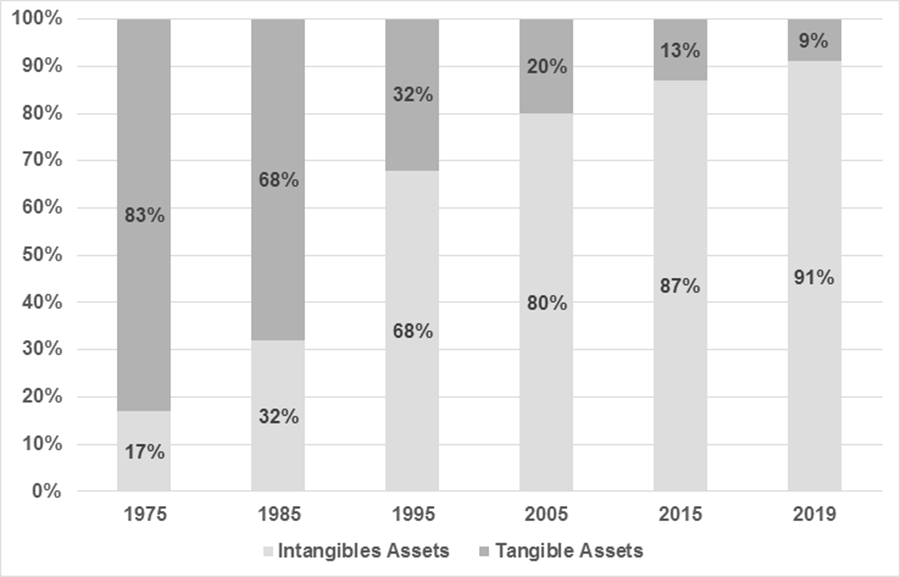

The digital transformation over the past thirty years has resulted in a new economic reality in which the basis of wealth and power is derived from the ownership of valuable intellectual property (IP), and more recently, the accumulation and control of data. IP and data are now the world's most valuable business and national security assets. This is best evidenced in the steady change of the Standard & Poors 500 Index (S&P500) over the last four decades. As shown in Figure 1, in 1975, about 17% of the value of the S&P500 was intangible assets, whereas today intangibles comprise over 91% of the S&P500 (Ocean Tomo, 2015) to the total of $22 trillion total in value (The Globe and Mail, 2019), and tangible assets account for only 5% of the total value of the world’s five most valuable companies.

Figure 1: Shift from tangibles to intangibles. Components of S&P 500 Market Value

Figure 1 shows a shift in the components of S&P market value, where tangible assets went from being the majority of overall assets in 1975 (83%) to the minority (9%) in 2019. Meanwhile, the proportion of intangible assets has increased over time, representing the minority in 1975 (17%) to the majority (91%) in 2019.

Source: Ocean Tomo, Intangibles Asset Market Value Study, 2015

In parallel, forward-looking governments started crafting updated economic development strategies that focused on supporting the generation, accumulation, commercialization and protection of IP.

Over the past ten years, the global economy expanded to include data assets, and the strategic focus turned to generating, exploiting and controlling these data assets . This includes the application of machine learning to produce artificial intelligence as well as generating valuable IP developed on top of data assets, creating a new policy challenge of machine generated IP. This unprecedented generation of IP (and data) stock assets demands urgent but sophisticated policy approaches for every nation, state or jurisdiction that competes in the global economy. This certainly includes Ontario.

The Expert Panel on Intellectual Property was created by the Government of Ontario, in Spring 2019, as part of its efforts to review, update and implement policy objectives that advance the prosperity of Ontario in the contemporary economy. The Expert Panel was asked to develop an action plan for the development of a provincial intellectual property framework that fully exploits the potential benefits of Ontario’s investments in research and development and maximizes the role that Ontario's innovation intermediaries can play in supporting this framework.

As Expert Panel members, we come from a wide range of backgrounds including postsecondary education, industry, technology and innovation, venture capital and investment, and intellectual property law:

- Jim Balsillie, businessman and philanthropist, retired Chairman and Co-CEO of Research In Motion (now BlackBerry), Chair of the Council of Canadian Innovators, and Chair of the Centre for International Governance Innovation

- Shiri Breznitz, PhD. Associate Professor, Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto

- Myra Tawfik, Professor of Law and EPICentre Professor of Intellectual Property Commercialization and Strategy, University of Windsor

- Dan Herman, Ph. D., cofondateur de MyJupiter Inc. et cofondateur du Centre for Digital Entrepreneurship & Economic Performance (DEEP)

- Natalie Raffoul, P.Eng. (Electrical Engineer), J.D. (Law), Registered Patent Agent, Managing Partner of Brion Raffoul Intellectual Property Law

To arrive at our recommendations, we have reviewed research on the rise of the IP-driven economy, best practices from relevant jurisdictions around the world and conducted 14 in-person consultations, with participation from over 110 individuals and more than 80 organizations.

We were encouraged by the enthusiastic participation and bold ideas shared at these consultations and a clear desire by many Ontarians to help the government get a robust picture of Ontario’s IP ecosystem and help it perform better for everyone involved in it. Consequently, our recommendations reflect the province’s challenge in optimizing such an ecosystem but also the opportunities it can advance, often with no additional funding, simply with better coordination among stakeholders.

Ontario’s challenge in today’s economy

In a recent speech delivered by Ontario’s Minister of Finance, Rod Phillips said this about Ontario’s GDP per capita performance:

When we talk about Ontario, some of us will recall when we were a top 10 North American jurisdiction, on par with our neighbours to the south like New York, who today is number five…. people are often surprised to find out we’re ranked 45th, one place ahead of Montana. We should be doing better, and we can do better.

(Toronto Star, October 10, 2019)

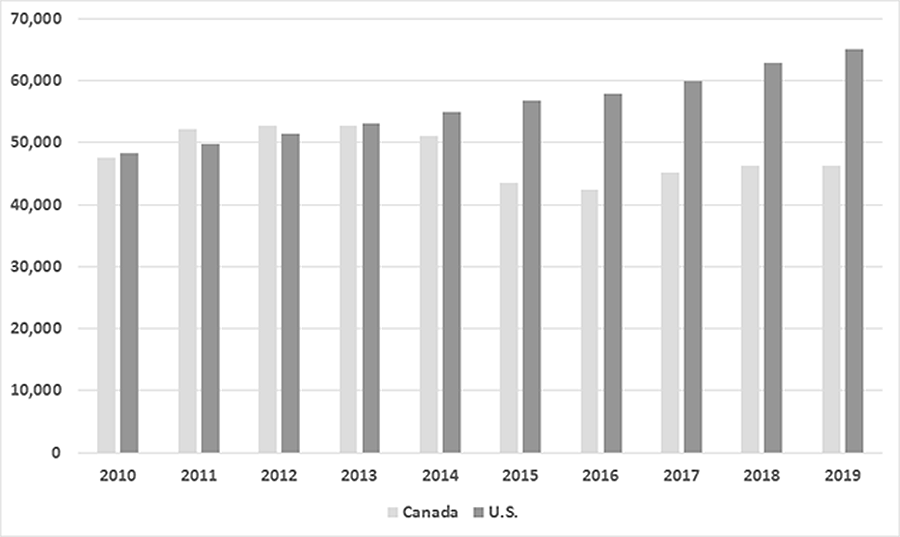

Figure 2: Canada – U.S. comparative GDP per capita performance

Figure 2 compares Canada’s GDP per capita to that of the U.S and shows the U.S. greatly surpassing Canada’s GDP per capita beginning in 2016. While the U.S. has seen growth in its GDP per capita in 2016 through to 2019, Canada’s GDP per capita has been in a moderate decline during the same period. Slight increases compared to previous years are seen for Canada in 2017 and 2018, yet GDP per capita remains below 2010 levels.

Ontario’s prosperity challenge is shared with the rest of the country. Data comparing Canada’s GDP per capita with that of the U.S. over the past decade demonstrates trends that have only very recently started to create a sense of alarm, and only by a select few monetary and fiscal policymakers. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Canada’s GDP per capita is 3% lower than our 2010 levels, while the US has experienced a 35% increase over the same period (International Monetary Fund, 2019) , due in part to the alignment of their economic policy infrastructure with knowledge-based and data-driven economic realities that, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce, contribute nearly $8 trillion annually to the U.S. economy. These outcomes correlate directly with individual citizens’ ability to consume products and services

An additional consideration that isn’t captured when looking at GDP per capita data, especially when employment rates see an increase, is the job quality index. In a recent study comparing the labour-market performance in Canadian provinces with U.S. states from 2015 to 2017, Canadian provinces significantly underperformed relative to U.S. states, with every Canadian province ranked in the bottom half of the 60 jurisdictions, (Fraser Institute, 2019, PDF).

Canadian workers were also much more likely to be stuck in involuntary part-time work, when they would otherwise want full-time work. On this indicator of under-employment, every Canadian province ranked in the bottom half.

In the late 1980s, when the economy was not as IP-intensive as it is today and our measure of employment quality was 15% higher, a 1% increase in employment generated, on average, a 4.4% increase in real labour income. Today, it generates less than 3%, (CIBC Economics, Tal Benjamin 2019.)

Top performers in these indexes come from jurisdictions that have evolved their prosperity strategies to generate stronger outcomes in this changed global economy.

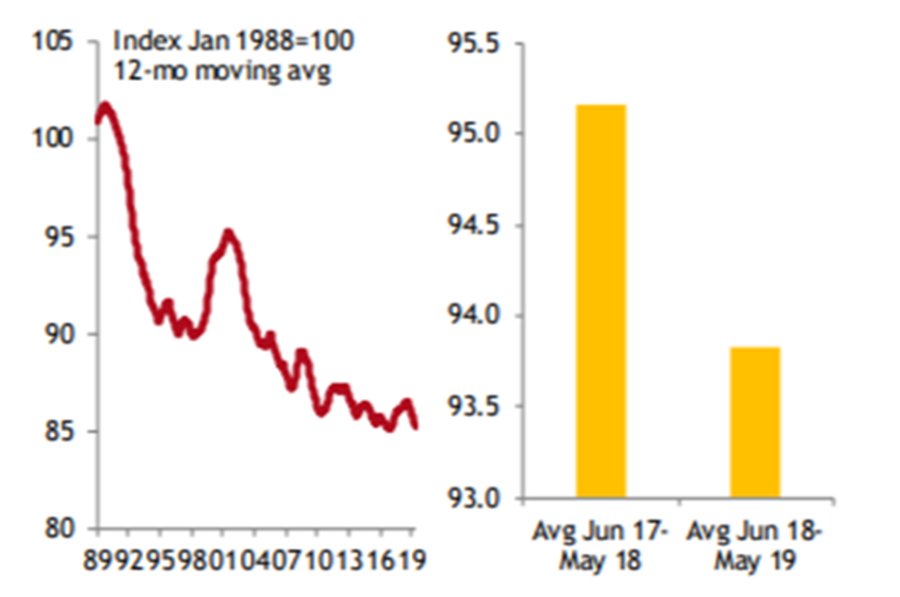

Figure 3: Canada Job Quality Index (Chart provided by CIBC)

The two charts in Figure 3 both illustrate CIBC’s Employment Quality Index for Canada, which is an index that combines information on the distribution of part-time vs. full-time jobs; self-employment vs. paid employment; and the compensation ranking of full-time paid employment jobs in more than 100 industry groups. The chart on the left shows a decline in the index from 1989 to 2019. The chart on the right demonstrates a decrease in the index from 2018 to 2019.

Source: CIBC tabulations based on Statistics Canada’s tabulation

A number of Ontario stakeholders can play a meaningful role in reversing these prosperity trends. These include small and medium size enterprises (SMEs), Ontario’s postsecondary education sector, incubators, accelerators and Regional Innovation Centres (RICs) that receive public funds to improve innovation outcomes. Equally, the government has a critical role in guiding the creation and implementation of policy strategies that help these stakeholders achieve desired prosperity outcomes.