Assisting the ewe at lambing

Learn how to best prepare for lambing, the stages of lambing and some of the signs of abnormal delivery. This technical information is for Ontario sheep producers.

ISSN 1198-712X, published September 2021.

Introduction

Being prepared for lambing season can increase the chances of having a lamb born alive. This fact sheet provides guidance on how to best prepare for lambing, the stages of lambing and some of the signs of abnormal delivery. The ewe’s gestation period ranges from 144–151 days in length, with an average of 147 days. The date that the first lambing is to be expected can be calculated from the date of the first exposure of the ewes to a fertile ram.

Preparing a lambing kit

Before lambing starts, prepare a kit of lambing aids. The essentials of this kit are:

- soap

- disinfectant

- obstetrical lubricant

- disposable obstetrical gloves

- sterile syringes — 10 mL and 1 mL

- hypodermic needles of sizes suitable for the ewe and the lamb

- antibiotics and vitamin E/selenium injections

- lambing cords and lamb snare

- iodine-based navel disinfectant

- clean towels or cloths

- clean pail for warm water

Disposable obstetrical gloves

It is always the best practice to wear disposable obstretical gloves when assisting a ewe during lambing. Wearing gloves reduces the risk of uterine infections for the ewe and the risk of zoonotic pathogens being transmitted to the producer (e.g., chlamydiosis, campylobacteriosis, cryptosporidiosis, listeriosis, toxoplasmosis or Q fever).

Lambing

Signs of impending lambing

About 10 days before the ewe will lamb, the teats begin to feel firm and full of colostrum. Between then and lambing, the lips of the vulva slacken and become slightly swollen. In the last hours before lambing, many ewes will separate from the flock. At this point, the ewe could be moved into a lambing pen, depending on your management system.

At birth, the normal presentation of a lamb is spine upwards, forefeet with the head between them pointing toward the cervix. The cervix itself is still sealed by a mucous plug. The lamb is surrounded by two fluid-filled sacs, the allantois and the chorion. These first and second waterbags have acted as cushions to prevent injury to the developing fetus and form part of the placenta. The placenta is attached to the wall of the ewe’s uterus by about 80 small buttons, the cotyledons. It is through these and the placenta that the developing lamb has received nutrients from the ewe’s blood supply. The placenta with the cotyledons will be expelled as the afterbirth.

Physiology of parturition (lambing)

The mechanism by which any mammal gives birth is stimulated by changes to the mother’s hormone balance and the bulk of the uterine contents, the fetus and the placental fluids. These stimuli cause the uterus to contract, pushing the fetus into the dilating cervix and expelling it.

Normal lambing

In a normal lambing, there are three distinct stages:

Dilation of the cervix

- As the uterine contractions start, a thick creamy white mucous, the remains of the cervical seal, is passed from the vulva. This often goes unnoticed.

- Continued contractions of the uterus push the first waterbag into the cervix, stimulating its dilation. Eventually the cervix will be about the same diameter as the neck of the uterus.

- The ewe is uneasy, getting up and down, switching her tail and bleating frequently.

- There may be some straining. This stage can take 3–4 hours.

Expulsion of the lamb

- As the uterine contractions become stronger and more frequent, the lamb and waterbags are pushed into the dilated cervix.

- The first waterbag bursts, releasing a watery fluid through the vulva.

- As the ewe continues to strain, the second waterbag is pushed through the vulva and ruptures, to release a thicker fluid. The rupturing of these bags has established a smooth, well‑lubricated passage through the vagina.

- The hooves and nose of the lamb can often be seen in the second waterbag before it bursts.

- The ewe continues to strain, gradually expelling the lamb, forefeet first, followed by the head.

- The ewe may need considerable effort to pass the head and shoulders of the lamb through her pelvis. Once this happens, final delivery is rapid.

- The birth of a single lamb should take an hour or less from the rupture of the first waterbag. A ewe lambing for the first time, or with multiple lambs, could take longer.

Expulsion of the placenta/afterbirth

- The placenta serves no further function once the lamb has been born and is passed 2–3 hours after delivery has finished.

- In multiple births, there will be separate afterbirths for each lamb.

Signs of abnormal deliveries

Most ewes will lamb unaided, and about 95% of lambs are born in the normal presentation, forefeet first. A normal delivery usually takes 5 hours from the start of cervical dilation to the delivery of the lamb, 4 hours for the dilation of the cervix and 1 hour for the actual delivery. The first 4 hours often go unnoticed. However, in the event of a problem, any delay in assistance could mean the difference between a live and dead lamb.

Signs that assistance may be needed:

- Ewe continues to strain, but there is no sign of the waterbags.

- Ewe continues to strain an hour after the rupture of the waterbags, but there is no sign of a lamb.

- The lamb appears to be wedged in the birth canal.

- There is an abnormal presentation, a leg back, head back, etc.

Making the internal examination

Cleanliness is important to prevent infection of the uterus. Wash the area around the ewe’s vulva with soap and a mild disinfectant to remove any manure and other debris. Scrub hands and arms with soap and a mild disinfectant, put on gloves and lubricate with soap or an obstetrical cream. Slide the gloved hand carefully into the vagina to feel the lamb and assess the situation. Obviously, a person with a small hand is best suited for this task.

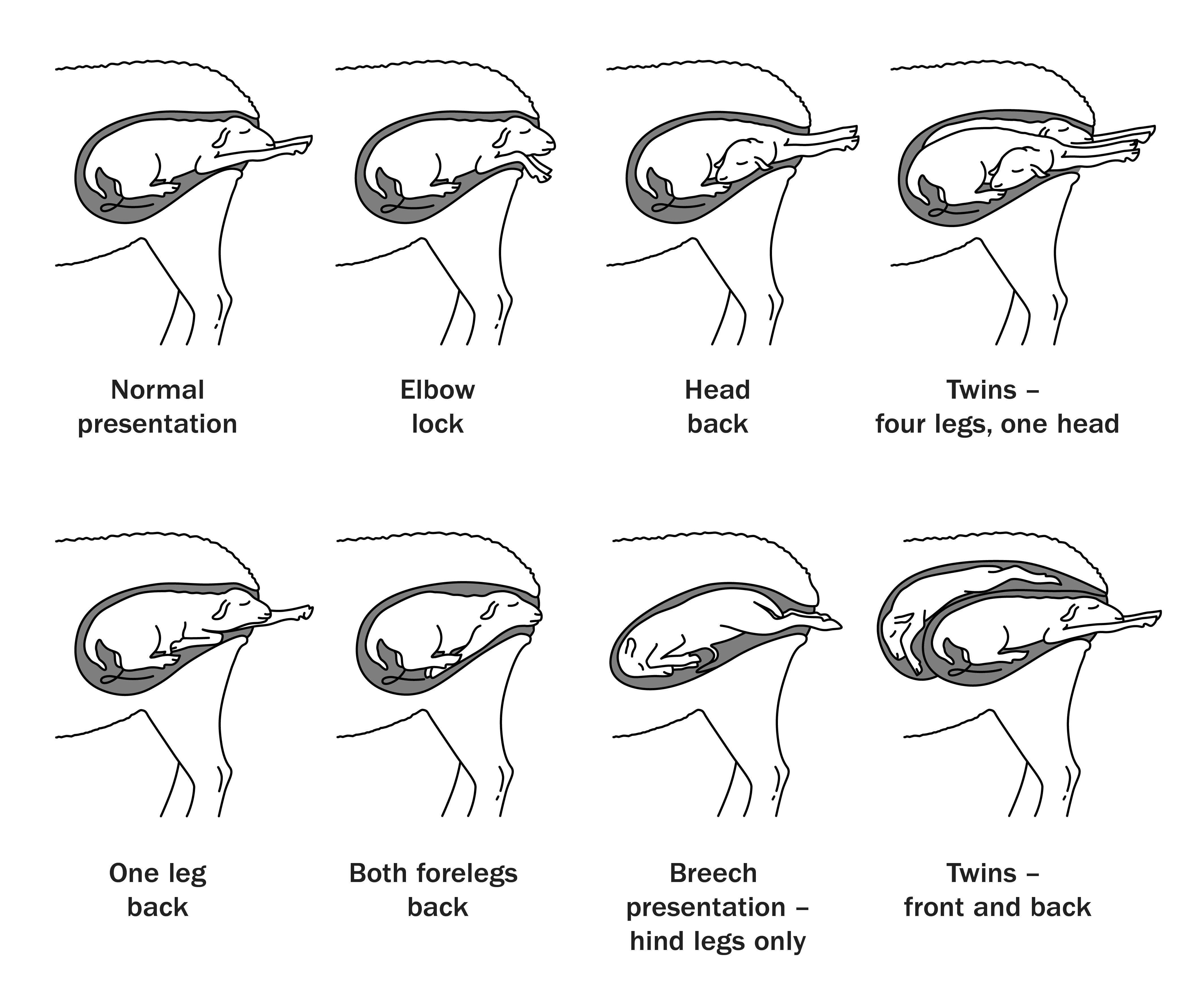

In many cases, the lamb will be presented normally — you will feel two forelegs with the head between them. In other cases, there will be a malpresentation with hind legs instead of fore legs, or one or both hind legs back, or a breech presentation where only the tail and rump are felt, Figure 1.

Resolutions

Normal presentation

- Place the noose of a lambing cord over each leg above the fetlock joint and apply a firm steady pull synchronized with the ewe’s straining.

- Lubricate the vagina around the lamb with obstetrical jelly to smooth the passage of the lamb. This is especially important if the waterbags have been ruptured for some time, and the vagina has lost this natural lubrication.

Abnormal presentations

- In most cases, the position must be corrected before attempting to pull the lamb.

- However, do not attempt to convert a hind leg presentation to the normal delivery. Pull the lamb out hind legs first, straight back until the lamb’s hind legs and pelvis are out of the vulva, then change the pull to downwards towards the ground behind the ewe. Pulling down before the lamb’s pelvis is out will wedge the lamb in the pelvic canal of the ewe. Remember that multiple births are common. Two lambs may be presented with legs intertwined. Always ensure that legs and head are part of the same lamb before attempting to pull them.

- Occasionally, deformed lambs will be produced with enlarged heads, stiff joints or skeletal deformities. To successfully lamb, a ewe in these situations may require help from an experienced shepherd or veterinarian.

- Ewes often have multiple births. The same sequence of the rupture of the waterbag and expulsion of the lamb will be repeated for the delivery of each lamb. After an assisted lambing, always check the ewe internally to ensure that there is not another lamb to be delivered.

Aftercare

In all cases, whether the delivery was natural or assisted, check that the lamb is breathing and that its nostrils are clear of mucous and not covered by any uterine membrane. At this time, the lamb’s navel should be disinfected with an iodine solution recommended by the flock veterinarian to prevent infection.

The ewe usually starts to lick the lamb. This is a natural process and should be allowed to continue. Some ewes will eat the afterbirth, but this should be prevented as it can lead to digestive disturbance. Afterbirth should be removed from the lambing site and disposed of according to the farm deadstock disposal plan.

A healthy lamb struggles to its feet soon after birth and starts to nurse from its dam. Lambs weak from a prolonged delivery should be helped to nurse or be given colostrum by stomach tube. The companion Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) fact sheet, Care of the newborn lamb, has more information on this.

After any assisted delivery, the ewe is at risk of infection. A protocol should be developed with the flock veterinarian that will ensure cleanliness and determine when antibiotics should be given.

Conclusion

Lambing is one of the most critical and challenging points in the sheep production cycle, requiring both careful observation and timely decision-making. Ensuring that you are adequately prepared, know the signs of impending lambing and can recognize abnormal deliveries that may require intervention, will increase the likelihood of survival of both the ewe and her lambs.

This fact sheet was originally written by John Martin, veterinary scientist, sheep, goat and swine, OMAFRA. It was updated by Delma Kennedy, sheep specialist, and Erin Massender, small ruminant specialist, OMAFRA.