Colicroot Recovery Strategy

This document is the recovery strategy for Colicroot, a species of plant at risk in Ontario.

Cover photo by M.J. Oldham

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation:

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2017. Recovery Strategy for the Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 6 pp. + Appendix.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2017

ISBN 978-1-4606-9783 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4606-9784-9 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration and images in the appended federal recovery strategy) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@ontario.ca.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Colicroot was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary of Ontario’s recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007(ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) is listed as endangered on the SARO List. The species is listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) in Canada in 2015 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Since the publication of the federal recovery strategy for Colicroot, a COSEWIC status assessment report has been published for the species. This report includes updated population estimates for Colicroot in Ontario, and identifies a threat (herbivory by deer) that was not identified in the federal recovery strategy.

There has been extensive transplanting, monitoring, and research on Colicroot in the Windsor area, in association with the construction of the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway. New information on this species' abundance, conservation techniques that can be used successfully to recover Colicroot, and recovery actions underway is provided.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy, together with scientific information on Colicroot and the communities it inhabits, be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA. This may include information provided in the updated COSEWIC status report.

Executive summary of Canada’s recovery strategy

Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) is an herbaceous perennial in the lily family reaching up to 1 m in height with white, tubular flowers which arise from a basal rosette of pale green, lance-shaped leaves. Flowering occurs between late June and late July.

Colicroot distribution ranges from New England west to Wisconsin and Illinois, and from Ontario south to eastern Texas and Florida (NatureServe 2012). In Canada, Colicroot is only confirmed as extant in the Windsor area (three populations) and on the Walpole Island First Nation in the St. Clair River delta, southwestern Ontario (two populations). The species is listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). It is also listed as Threatened in Ontario under the provincial Endangered Species Act, 2007.

Threats identified to the Canadian population of Colicroot include, but are not limited to: habitat loss or degradation, changes to ecological dynamics or natural processes, invasive species and disturbance from recreational activities.

Recovery of Colicroot in Canada is considered to be feasible. The population and distribution objectives are to maintain, or increase where biologically and technically feasible, the current abundance and distribution of extant Colicroot populations in Canada. The broad strategies to be taken to address the threats to the survival and recovery of the species are presented in the section on Strategic Direction for Recovery (Section 6.2).

Critical habitat for Colicroot is partially identified in this recovery strategy based on the best available data. Critical habitat for Colicroot is located entirely on non-federal lands, As more information becomes available, additional critical habitat may be identified and may be described within an area-based, multi-species at risk action plan developed in collaboration with the Walpole Island First Nation.

One or more such action plans for Colicroot will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by December 2021.

Adoption of federal recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) is listed as endangered on the SARO List. The species is listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) in Canada in 2015 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Species assessment and classification

Table 1. Species assessment and classification of the Colicroot (Aletris farinosa). The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations within, and for other technical terms in this document

|

Assessment |

Status |

|---|---|

|

SARO list classification |

Endangered |

|

SARO list history |

Endangered (2017), Threatened (2008), Threatened – Not Regulated (2004) |

|

COSEWIC assessment history |

Endangered (2015), Threatened (2000), Threatened (1988) |

|

SARA schedule 1 |

Threatened |

|

Conservation status rankings |

GRANK: G5 NRANK: N2 SRANK: S2 |

Species description and biology

MacPhail (2013) investigated pollinators of Colicroot at two Parkway sites in the City of Windsor in 2013. A total of 25 species of insects were observed, of which seven species (28%) were in common between sites. Colicroot was found to be visited primarily by bumblebees (Bombus bimaculatus, Bombus sp.) and solitary bees (especially Agapostemon virescens and Anthophora terminalis). Nectar and/or pollen were collected, depending on the type of insect visitor. Some solitary bees and bumble bee workers carried pollen, while male bumble bees (more common than the female workers) and other visitors foraged on nectar. Colicroot was previously known to be pollinated by bumble bees and bee flies; this study confirms and provides more details on the bumble bee aspect but also adds additional species of potential pollinators (MacPhail 2013).

Distribution, abundance and population trends

The recent assessment by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, COSEWIC (2015), provides the following information on abundance and population trends. Total abundance in Ontario during 2014 was between 14,000 and 15,000 plants, with approximately 14,600 considered to be the best available estimate. Most of the Ontario population known in 1986 has been lost. Assuming newly discovered plants existed previously in addition to the plants recorded from the previously documented subpopulations, there may have been a base population of at least 18,330 in 1986. Since then, there has been a measurable loss of more than 5,000 plants or 27% of the population, with the actual decline well upwards of that (COSEWIC 2015).

Between 2008 and 2015, several Colicroot subpopulation estimates have been made at the Rt. Honorable Herb Gray Parkway site in Windsor, Ontario. The subpopulation of Colicroot at the Parkway site in 2008 was estimated to be 922 in number at five separate locations. In 2012, preliminary to Parkway construction mitigation efforts, an estimated 6,515 to 9,728 plants were identified in the Parkway area (COSEWIC 2015). Greenhouse propagation, followed by out-planting of plugs, and prairie sod mat transfer occurred between 2009 and 2014. By these means, approximately 10, 368 plants were introduced to five separate restoration sites, 7, 352 in sod mats (not including banked seed) and 3, 016 as plugs (WEMG 2016). As of 2015, transferred sod mats had exhibited a net increase in the number of observable plants of 2, 647, for a total of 9, 999 plants, and 1, 326 of the out-planted plugs had survived (S. Snyder pers. comm. 2017). This represents a total increase of approximately 3, 973 growing plants, most of which were either produced through post-restoration reproduction or emerged from the seed bank in response to habitat manipulation. Consequently, the 2015 population estimate of Colicroot within Parkway restoration sites is 13,667, about 2,342 of which were naturally occurring at the sites prior to restoration efforts (based on 2008-2010 surveys (D. Barcza, pers. comm. 2017) and 11, 325 were introduced, directly or indirectly, through restoration efforts.

The Ontario population of Colicroot totalled about 16,270 plants in 2015. This is the sum of the approximately 13,670 plants believed to be extant in the Rt. Honorable Herb Gray Parkway area and the 2, 600 plants believed to occur elsewhere in Ontario (COSEWIC 2015).

Threats to survival and recovery

Herbivory

The COSEWIC report (2015) identifies herbivory by deer as a low to medium level of threat to Colicroot.

Recovery actions completed or underway

Colicroot transplanting and germination-propagation trials have proceeded as part of construction of the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway in Windsor, Ontario. These trials have allowed for the identification and refinement of mitigation and restoration methods that are likely to be effective in application to Colicroot.

Germination-propagation : A seeding trial, whereby seeds from mature plants were dispersed at restoration sites, was undertaken but no germination of dispersed seed was observed. However, a reliable method of propagating Colicroot from collected seed and out-planting it at restoration sites was successfully developed. This is a significant achievement since it is the first time that Colicroot has been successfully grown from seed in a greenhouse and produced viable plants that have flowered and persisted on the landscape. While the documented techniques promise to contribute to future recovery efforts for Colicroot, further investigation is warranted to demonstrate that the results of the method can be replicated.

Transplanting: A number of Colicroot transplanting trials were undertaken. One trial involving rhizome cuttings was initiated but aborted because rhizomes were too small for division. Sod mat transplantation was the method used to transplant all of the in situ plants on the Parkway and it has proven to be a very effective mitigation method. Ex situ propagation of sod mats in greenhouses was also found to successfully stimulate asexual reproduction prior to transplanting (LGL and AECOM 2017).

In addition to increasing knowledge of restoration methods that can be used to recover Colicroot, the field trials and subsequent mitigation efforts have increased the total number of Colicroot plants within the combined Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway impact and restoration areas. At present, the number of growing plants at the transplant sites represents an increase of 1,326 to 3, 973 plants. Numbers of plants (including banked seed) that were represented in transplanted sod mats prior to intervention are impossible to estimate at the current time; however, given the state of the sites from which these mats were taken, it appears unlikely that increases in seed germination and production would have occurred. Rather, given that these sites were privately owned, unmanaged and unprotected, it is probable that declines which have been observed elsewhere would also have occurred at these locations. In contrast, within the restoration sites, tallgrass prairie inhabited by Colicroot is expected to be managed to the benefit of Colicroot on an ongoing basis into the future. Colicroot populations will be monitored by MTO until 2020 under ESA authorization conditions, and beyond 2020 by a long-term steward.

Approaches to recovery

New information under the section on Threats to Survival and Recovery above is not discussed in the federal recovery strategy. The federal recovery strategy does not include recovery actions to address these threats. Therefore, consideration should be given to relevant recovery actions that would help to address these new threats when developing recovery initiatives for this species in Ontario.

Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below will be one of many sources considered by the Minister, including information that may become newly available following completion of the recovery strategy, when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy, together with scientific information on Colicroot and the communities it inhabits, be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Updated information on the status of Ontario Colicroot subpopulations is available (COSEWIC 2015). This includes updated population and habitat information for the population in Eagle (West Elgin, Ontario) not currently identified as federal critical habitat.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Ranks are determined by NatureServe and, in the case of Ontario’s S-rank, by Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

NR = not yet ranked

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Barcza, Dan, personal communications 2017. Email correspondence, April 2017.President,Terrestrial and Restoration Ecologist, Sage Earth.

COSEWIC. 2015. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Colicroot Aletris farinosa in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiii + 39 pp.

LGL, Sage Earth/Restoration Services and AECOM. 2017. Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) Trials Summary Monitoring Report, The Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway. Draft prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation.

MacPhail, V.J. 2013. Investigating the Pollination Biology of Species-At-Risk Plants in Southern Ontario: Results from 2013. Unpublished report prepared for Wildlife Preservation Canada Guelph, Ontario. 36 pp.

Snyder, Season, personal communications. 2017. Email correspondence, April 2017. Senior Plant Ecologist, AMEC Foster Wheeler

WEMG. 2016. 2015 Annual Monitoring Report for Plant Species at Risk, The Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway, Volume 1 - Mitigation and Monitoring. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation. pp 125-126.

Appendix 1. Recovery strategy for the Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) in Canada

Federal cover illustration: Gary Allen

Recommended citation:

Environment Canada. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vi + 30 p.

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry

Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de l'alétris farineux (Aletris farinosa) au Canada »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2015. All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-0-660-03363-1

Catalogue no. En3-4/202-2015E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996)

The Minister of the Environment is the competent minister under SARA for the Colicroot and has prepared this strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. To the extent possible, it has been prepared in cooperation with the Province of Ontario.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Colicroot and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment Canada and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

The recovery strategy sets the strategic direction to arrest or reverse the decline of the species, including identification of critical habitat to the extent possible. It provides all Canadians with information to help take action on species conservation. When the recovery strategy identifies critical habitat, there may be future regulatory implications, depending on where the critical habitat is identified. SARA requires that critical habitat identified within federal protected areas be described in the Canada Gazette, after which prohibitions against its destruction will apply. For critical habitat located on federal lands outside of federal protected areas, the Minister of the Environment must either make a statement on existing legal protection or make an order so that the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat applies. For critical habitat located on non-federal lands, if the Minister of the Environment forms the opinion that any portion of critical habitat is not protected by provisions in or measures under SARA or other Acts of Parliament, and not effectively protected by the laws of the province or territory, SARA requires that the Minister recommend that the Governor in Council make an order to extend the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat to that portion. The discretion to protect critical habitat on non-federal lands that is not otherwise protected rests with the Governor in Council.

Acknowledgments

This version of the recovery strategy was prepared by Judith Jones, Winter Spider Eco-Consulting. The Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) Aylmer District provided records of Colicroot. Thanks are extended to Allen Woodliffe (formerly with MNR-Aylmer) and Don Kirk (MNRF-Guelph) for assistance with the draft recovery strategy. The original draft of this recovery strategy was developed by the Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario Recovery Team, Al Harris (Northern Bioscience), Gerry Waldron (consulting ecologist), and Carl Rothfels (Duke University) with input from John Ambrose (Cercis Consulting), Jane Bowles (University of Western Ontario), Allen Woodliffe (formerly with MNR-Aylmer), Peter Carson (Pterophylla), Graham Buck (Brant Resource Stewardship Network), Paul Pratt (Ojibway Nature Centre), and Ken Tuininga (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service - Ontario). Ken Tuininga, Angela Darwin, Krista Holmes, Janet Lapierre and Christina Rohe (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) provided further revisions to the recovery strategy. Contributions from Susan Humphrey, Lesley Dunn, Elizabeth Rezek and Madeline Austen (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) are also gratefully acknowledged.

Executive summary

Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) is an herbaceous perennial in the lily family reaching up to 1 m in height with white, tubular flowers which arise from a basal rosette of pale green, lance-shaped leaves. Flowering occurs between late June and late July.

Colicroot distribution ranges from New England west to Wisconsin and Illinois, and from Ontario south to eastern Texas and Florida (NatureServe 2012). In Canada, Colicroot is only confirmed as extant in the Windsor area (three populations) and on the Walpole Island First Nation in the St. Clair River delta, southwestern Ontario (two populations). The species is listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). It is also listed as Threatened in Ontario under the provincial Endangered Species Act, 2007.

Threats identified to the Canadian population of Colicroot include, but are not limited to: habitat loss or degradation, changes to ecological dynamics or natural processes, invasive species and disturbance from recreational activities.

Recovery of Colicroot in Canada is considered to be feasible. The population and distribution objectives are to maintain, or increase where biologically and technically feasible, the current abundance and distribution of extant Colicroot populations in Canada. The broad strategies to be taken to address the threats to the survival and recovery of the species are presented in the section on Strategic Direction for Recovery (Section 6.2).

Critical habitat for Colicroot is partially identified in this recovery strategy based on the best available data. Critical habitat for Colicroot is located entirely on non-federal lands, As more information becomes available, additional critical habitat may be identified and may be described within an area-based, multi-species at risk action plan developed in collaboration with the Walpole Island First Nation.

One or more such action plans for Colicroot will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by December 2021.

Recovery feasibility summary

Based on the following four criteria that Environment Canada uses to establish recovery feasibility the recovery of the Colicroot is considered to be feasible.

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

- Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

- The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

- Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

COSEWICfootnote * Species assessment information

Date of Assessment: November 2000

Common Name: Colicroot

Scientific Name: Aletris farinosa

COSEWIC Status: Threatened

Reason for Designation: This perennial herb has few populations remaining which are highly localized in two remnant prairie habitats in southwestern Ontario. Habitat conversion is a continued threat.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Threatened in April 1988. Status re-examined and confirmed in November 2000.

Species status information

Globally, Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) is regarded as Secure

In Canada, Colicroot is ranked Imperiled both nationally (N2) and provincially (S2) in Ontario (NatureServe 2012).

Colicroot is listed as Threatened

The percentage of the global range found in Canada is estimated to be less than 5%. The distribution of Colicroot is very restricted in Canada, where it occurs near the northern extent of its North American range.

Species information

Species description

Colicroot is an herbaceous perennial in the lily family (Liliaceae) and is the only member of its genus in Canada. A basal rosette of pale green, lance-shaped leaves (8 cm to 20 cm long) emerge from a short, thick underground stem (rhizome). Between late June and late July, a slender scape/stalk arises, terminating in a spike-like raceme

Population and distribution

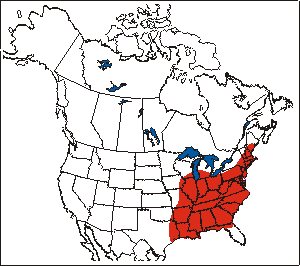

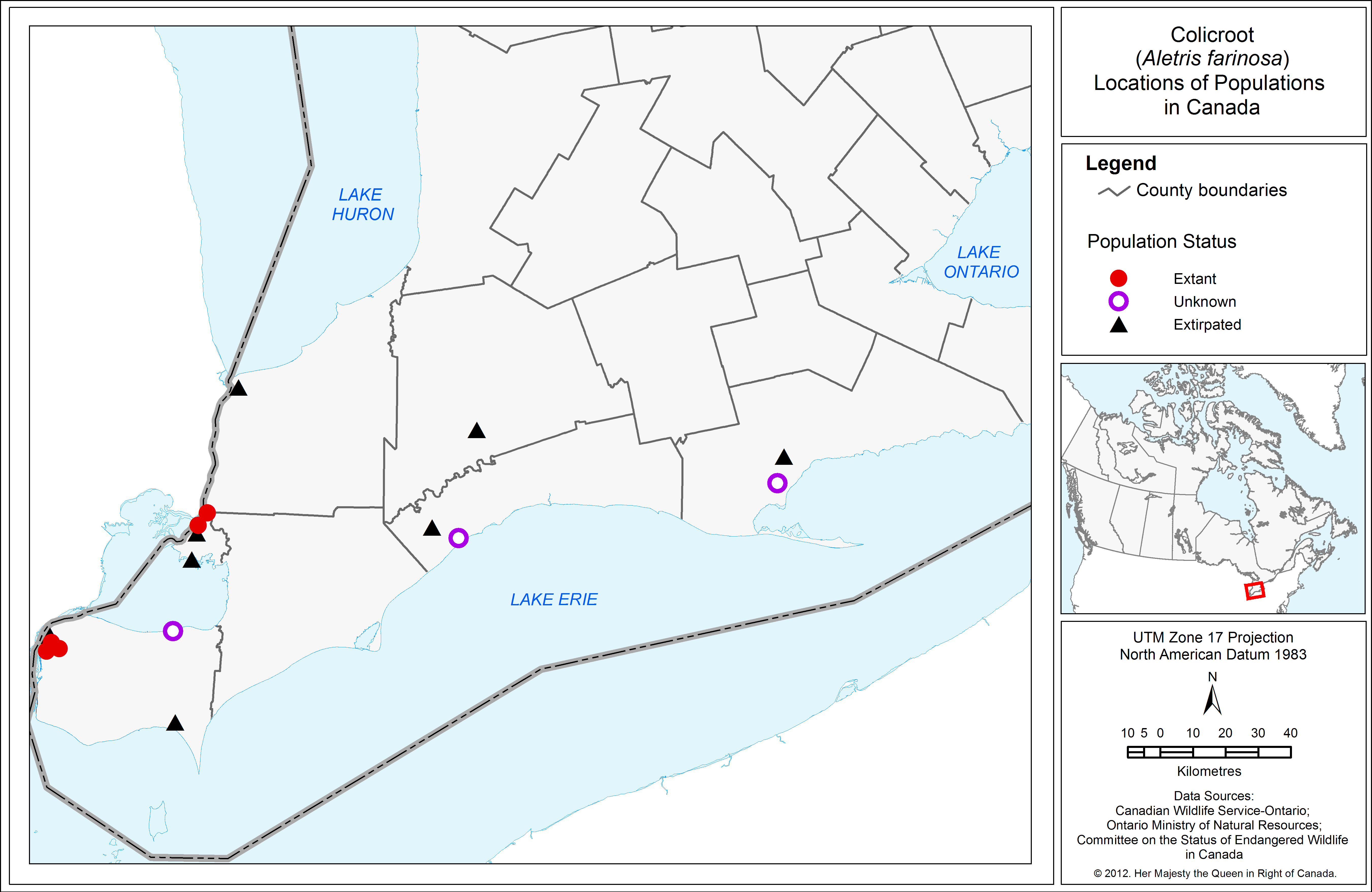

Globally, Colicroot is endemic to North America. In the United States, its range extends across much of the eastern part of the country, from New England west to Wisconsin and Illinois, and south from Virginia to Texas (Figure 1; Appendix D). Colicroot is now considered extirpated and probably extirpated in Maine and New Hampshire respectively (NatureServe 2012). In Canada, Colicroot is only found in southwestern Ontario, where it is considered to be at the northern edge of its range (Figure 2). It occurs in local populations and throughout its range it is largely absent from extensive areas (Kirk 1988).

Groups of plants separated from each other by more than 1 km are generally recognized as separate populations/occurrences in the COSEWIC, NatureServe and Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) records for vascular plants. Groups of plants that are closer to each other than 1 km are considered subpopulations of a single population (NHIC 2011). Using this definition, there are five populations with several associated subpopulations considered to be extant and three additional populations of unknown status in Ontario (Figure 2; Table 1).

Two of the five extant populations are found in the Walpole Island First Nation and the other three are in the Windsor area in Essex County. The three populations in the Windsor area are described as follows: the Ojibway Prairie Complex, LaSalle Woodlot Environmentally Significant Area (ESA) and the Reaume Prairie ESA (Table 1). Aside from surveys in the Windsor area associated with the construction of the Detroit River International Crossing and the Right Honourable Herb Gray Parkway (HGP), there have been few Colicroot surveys in the last two decades. Further investigation is required in Essex, Elgin and Norfolk counties to determine the abundance of the three populations of unknown status.

Portions of several Colicroot subpopulations were formerly located in the corridor being developed for the HGP. Within the Ojibway Prairie Complex and the LaSalle Woodlot ESA populations the portions of the Colicroot subpopulations that extended into the HGP footprint were removed and transplanted to restoration sites adjacent to the HGP under a permit issued under the provincial Endangered Species Act, 2007. The permit also required the proponent to carry out trials of different restoration techniques between 2009 and 2012 which have been largely successful (LGL Ltd. 2013; AMEC 2013) (described in Section 6.1). With this in mind, the abundance information in Table 1 is quickly dated and subject to change. Restoration sites will be added once the transplanted plants have had time to establish and their success determined.

Ten extirpated populations (NHIC 2011) are listed in Appendix B.

Figure 1. The Global distribution of Colicroot (modified from Argus et. al. 1982 – 1987)

Figure 2. The Canadian range of Colicroot (Environment Canada 2012). Due to lack of spatial reference, two extirpated populations have not been included. For a full list of populations and subpopulations, including those with extant and unknown status, see Table 1. For a list of extirpated populations see Appendix B

Table 1. The Canadian Populations and Subpopulations of Colicroot footnote *

|

Population and subpopulations |

Last Observed |

Abundance at last observation |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Walpole Island First Nation - Population #1 |

2014 |

~100 flowering stems |

Extant |

|

2. Walpole Island First Nation - Population #2 |

2014 |

~10 flowering stems |

Extant |

|

3. Ojibway Prairie Complex |

|||

|

Ojibway Prairie Provincial Nature Reserve |

2005 |

Hundreds to thousands of plants (1987) |

Extant |

|

Spring Garden Natural Area |

1994 |

190 flowering stems (1987) |

Extant |

|

HGP |

2008 |

1 526 flowering stems |

Extant |

|

HGP #2 (near Spring Garden/Lamont ) |

2008 |

1 flowering stem |

Extant |

|

"Ball Diamond" |

2008 |

Approximately 600 - 700 plants |

Extant |

|

Tallgrass Prairie Heritage Park, Kirk (1987) #5 |

1987 |

No information |

Unknown |

|

North of Windsor Raceway. Kirk (1987) #9 |

1986 |

Single rosette |

Unknown |

|

4. LaSalle Woodlot ESA |

|||

|

HGP #3 (near Huron Church/Todd) |

2008 |

3 531 flowering stems |

Extant |

|

HGP #4 (near Huron Church) |

2008 |

18 flowering stems |

Extant |

|

HGP #5 (near Huron Church/St Clair) |

2008 |

30 flowering stems |

Unknown |

|

Kirk (1987) Essex #3 |

1987 |

No information |

Unknown |

|

Kirk (1987) Essex #4 |

1987 |

No information |

Unknown |

|

Near Oakwood Park, Windsor, Kirk (1987) Essex #10 |

1984 |

No information |

Unknown |

|

Near Brunet Park |

1993 |

~1000 flowering stems |

Unknown |

|

5. Reaume Prairie ESA |

2012 |

30- 40 flowering stems, additional rosettes present |

Extant |

|

Ruscom Shores Conservation Area |

1983 |

No information |

Unknown |

|

Eagle (southeast of West Lorne) |

1993 |

~60 plants |

Unknown |

|

Turkey Point |

1996 (Not found in 2002) |

10-20 plants |

Unknown |

Needs of the Colicroot

In Canada, Colicroot primarily inhabits moist tallgrass prairie and oak savanna communities, although some plants occur in old field, roadside and woodland edge habitats (Kirk 1988; COSEWIC 2000). It occurs on soil characterized as coarse-textured, sand or sandy loam with a neutral to somewhat acidic pH (4.7 to 7.0) (Kirk 1988). The species may also be found in forest openings and sand pits given suitable habitat conditions (Kirk 1988; Kirk pers. comm. 2011).

Colicroot is intolerant of shading from woody plants and dense herbaceous growth (Kirk 1988). In the absence of fire, the species is dependent on disturbance, provided that the soil is not disturbed to a depth of more than a few centimetres, to maintain the open habitat from competing vegetation and thatch

Colicroot occurs in the Carolinian region of southwestern Ontario. Although the species' habitat is subject to seasonal extremes in moisture conditions (e.g., spring flooding and summer drought) (Lee et al. 1998; Kost et al. 2007), this region has one of the warmest climates and longest growing seasons in Canada (White and Oldham 2000). Kirk (1988) notes, the drought conditions, high humidity and high summer temperatures of this region, characterize a climate typical of the northern Midwest United States (e.g. Minnesota, Wisconsin).

Colicroot does not appear to transplant well (Harris 2009), suggesting it may have an obligate symbiotic relationship

Currently, there is little information on Colicroot pollinators, although other species of Aletris are pollinated by bumblebees (Bombus spp.) and beeflies (Bombylius spp.) (Kirk 1988).

Threats

4.1 Threat assessment

Table 2. Threat assessment table

|

Threat |

Level of Concern1 |

Extent |

Occurrence |

Frequency |

Severity2 |

Causal Certainty3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Development (e.g. housing, commercial, infrastructure) |

High |

Widespread |

Historic / Current / Anticipated |

Recurrent |

High |

High |

|

Agricultural expansion |

High |

Localized |

Historic/ Current |

Recurrent |

High |

High |

|

Dumping (e.g. fill, garbage) |

Medium |

Localized |

Historic/ Current |

Continuous |

Unknown |

Medium |

Changes in ecological dynamics or natural processes

|

Threat |

Level of Concern1 |

Extent |

Occurrence |

Frequency |

Severity2 |

Causal Certainty3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alteration of natural fire regime |

High |

Widespread |

Current |

Continuous |

High |

Medium |

Disturbance or harm

|

Threat |

Level of Concern1 |

Extent |

Occurrence |

Frequency |

Severity2 |

Causal Certainty3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Incidental harm (e.g. from mowing, off-road vehicles and trail use) |

Medium |

Localized |

Current |

Continuous |

Moderate |

Medium |

Introduced and invasive species

|

Threat |

Level of Concern1 |

Extent |

Occurrence |

Frequency |

Severity |

Causal Certainty3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Invasive species (e.g. Scots Pine, Common Reed, Autumn Olive, Multiflora Rose etc.) |

Low-Medium |

Localized |

Current |

Continuous |

Unknown |

Medium |

Sources: (COSEWIC 2000; Woodliffe pers. comm.2010; Pratt pers. comm.2010; and Jacobs pers. comm. 2010).

2Severity: reflects the population-level effect (High: very large population-level effect, Moderate, Low, Unknown)

3Causal certainty: reflects the degree of evidence that is known for the threat (High: available evidence strongly links the threat to stresses on population viability; Medium: there is a correlation between the threat and population viability e.g. expert opinion; Low: the threat is assumed or plausible).

4Threat categories are listed in order of decreasing significance.

4.2 Description of threats

Development and agricultural expansion

In Ontario, only about 2 100 ha or 0.5% of the prairie and savanna present in the 19th century remains, with the majority of tallgrass prairie lost to agricultural and residential development (Bakowsky and Riley 1994). Most populations of Colicroot in Canada are on open ground that is vulnerable to residential, commercial and infrastructure development. Expansion of several agricultural fields has destroyed multiple populations in Lambton and Essex counties (NHIC 2011).

Alteration of the fire regime

Alteration of the natural fire regime or other limited disturbance can alter suitable habitat by allowing trees and shrubs to grow and eventually shade out the species. Periodic prescribed burning is conducted on the Ojibway Prairie Complex and on parts of the Walpole Island First Nation. It is also required at other sites to prevent prairie habitats from converting to woodlots. Succession was the likely cause of the disappearance of the Elgin County population as well as one of the Walpole Island First Nation subpopulations (White and Oldham 2000).

Dumping

Dumping of fill and garbage has probably extirpated the population at Turkey Point and may threaten some of the other subpopulations in the Windsor area (White and Oldham 2000).

Incidental harm

Off-road or all-terrain vehicle (ATV) and off-trail use can result in direct damage to an individual plant through trampling and compaction of the soil, thus making habitat unsuitable. The effects of off-road vehicles and other recreational activities were noted by Oldham (2000) on unfenced public and private sites in Windsor and LaSalle.

Mowing of prairie habitat that may contain Colicroot also occurs at some sites around Windsor that are outside of protected areas (Woodliffe pers. comm. 2010). Although Colicroot does not grow well with competing vegetation, mowing does not normally result in suitable habitat conditions for Colicroot and may potentially harm Colicroot plants.

Invasive species

Population and distribution objectives

The population and distribution objectives are to maintain, or increase where biologically and technically feasible, the current abundance and distribution of extant Colicroot populations

The priority for increasing the current abundance and distribution of Colicroot populations is through management of habitat of extant populations, including those created under permit for the HGP, i.e. a more natural increase as opposed to reintroductions to sites from which Colicroot has been extirpated. Where possible, however, introduction at historical sites that have suitable habitat should be considered for biological and technical feasibility.

Broad strategies and general approaches to meet objectives

Actions already completed or currently underway

Several subpopulations are in provincially and municipally protected areas within the Ojibway Prairie Complex and are managed to conserve Colicroot and other tallgrass prairie plants and habitat. As well, the Reaume Prairie and LaSalle Woodlot sites are designated Environmentally Significant Areas (ESAs) in the official plan of the Town of LaSalle, thereby receiving additional consideration for protection in the planning process.

On the Walpole Island First Nation tallgrass prairie and savanna communities undergo periodic prescribed burns. The Ojibway Prairie Provincial Nature Reserve, Tallgrass Prairie Heritage Park, and Spring Garden Natural Area have active prescribed burn programs as well.

Recovery actions described in the Draft Walpole Island Ecosystem Recovery Strategy (Bowles, 2005) include raising awareness in the community about species at risk, including Colicroot. Pamphlets, calendars, newsletter articles, posters and other promotional material have been used to raise awareness of species at risk in the Walpole Island First Nation community.

The Walpole Island First Nation is currently developing an ecosystem protection plan based on the community’s traditional ecological knowledge (TEK).

Efforts by the Walpole Island Heritage Centre to lease lands for conservation have resulted in a reduction in the rate of conversion of prairie and savanna habitat to agriculture (COSEWIC 2009) during the tenure of the 5-year leases. The Walpole Island Land Trust was established in 2008 to conserve land on the Walpole Island First Nation (Jones 2013). Over 300 acres of land with tallgrass prairie, oak savanna and forest habitats have been acquired since 2001 for conservation (Jacobs 2011), benefitting species at risk such as Colicroot.

In the Windsor area, the construction of a divided multi-lane highway (the Herb Gray Parkway, or HGP) resulted in impacts to a portion of the Colicroot subpopulations in the Ojibway Prairie Complex and LaSalle Woodlot Environmentally Significant Area. In 2010, the Minister of Natural Resources issued a permit under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 to the Ministry of Transportation for the construction of the HGP. The permit identified several conditions to mitigate impacts to Colicroot, including creating restoration sites, developing a restoration and management plan, and completing several transplanting and propagation trials. The management plan identifies measures for habitat enhancement, including invasive species management and adaptive management strategies.

The purpose of the transplanting and propagation trials was to identify techniques for transplanting and propagating Colicroot, because the species was not known to transplant well, or grow successfully from seed. Trials conducted included timing of transplanting (spring, summer, or fall), seed dispersal into appropriate habitat, rhizome cutting, and growing Colicroot lifted from impact sites in a greenhouse to promote growth and reproduction. Many of the trials resulted in successful transplantation of Colicroot, with the notable exception of rhizome cutting. Trials revealed that Colicroot rhizomes were too small to cut. With respect to propagation trials, direct seeding into appropriate habitat was not successful, however, trials showed that cold moist stratification resulted in successful germination and growth of Colicroot seed. The most successful transplanting trial was lifting sods in fall and transplanting the sods into appropriate habitat prepared ahead of time by scraping away existing vegetation at the receptor site. This technique was employed in the fall of 2012 to transplant the impacted population. Large sods (approximately 1 m2), were lifted with soil intact, and planted into restoration sites. All planted and transplanted individuals are being monitored from the time of planting until five years after construction is completed (LGL Ltd. 2013; AMEC 2013).

Strategic direction for recovery

Table 3. Recovery planning table

|

Threat or Limitation |

Priority |

Broad Strategy to Recovery |

General Description of Research and Management Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

|

All threats |

High |

Assess / monitor populations |

|

|

All threats |

High |

Protect, conserve and manage habitat |

|

|

Knowledge gaps relating to recruitment and biological needs and impacts of threats |

High |

Conduct research |

Examples of knowledge gaps:

|

|

All threats |

Medium |

Outreach and education |

|

|

Habitat loss or degradation |

Medium |

Habitat restoration |

|

Critical habitat

Identification of the species' critical habitat

Critical habitat is defined in the Species at Risk Act (S.C.2002, c29) section 2(1) as "the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species' critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species".

Critical habitat for Colicroot is partially identified in this recovery strategy, to the extent possible, based on best available information. It is recognized that the critical habitat identified below is insufficient to achieve the population and distribution objectives for the species, because it has only been identified for three of five known extant populations. Available information on the species at a number of locations is outdated or lacking detailed spatial references. The Schedule of Studies (Section 7.2; Table 4) outlines the activities required for identification of additional critical habitat necessary to support the population and distribution objectives. More precise critical habitat boundaries may be identified, and additional critical habitat may be added in the future, as new information becomes available.

The identification of critical habitat for Colicroot is based on two criteria: suitable habitat and site occupancy.

Suitable habitat

Colicroot is found on damp sand or sandy loam in tallgrass prairie and oak savanna communities, old fields and woodland edges where the pH of the soil ranges from neutral to slightly acidic (4.7 to 7.0) (Kirk 1988). Scarified or bare sandy substrate from human disturbance may provide suitable open ground in the absence of fire. Colicroot may be found in large open areas or in smaller openings within another vegetation type (e.g. forest) given suitable soil type, moisture and pH conditions. Within these suitable habitat areas, the vegetation immediately adjacent to Colicroot typically consists predominantly of herbaceous plants, especially grasses (Appendix C). Both natural and human disturbances create and maintain the openness of habitat (prevent shading by competing vegetation), contributing to the suitability of habitat for Colicroot. Therefore, suitable habitat for Colicroot is described as natural or semi-naturalized habitat.

Natural habitat suitable for Colicroot includes tallgrass prairie and savanna. The Ecological Land Classification (ELC) framework for Ontario (from Lee et al. 1998) can be used to describe this habitat. Colicroot is documented to occur within the following ELC ecosite designations:

- Fresh-Moist Tallgrass Prairie (TPO2)

- Fresh-Moist Tallgrass Savanna (TPS2)

The ELC framework provides a standardized approach to the interpretation and delineation of dynamic ecosystem boundaries. The ELC approach classifies habitats not only by vegetation community but also considers hydrology and topography, and as such provides a basis for describing the ecosystem requirements of the natural habitat for Colicroot.

Semi-naturalized habitats such as old field, roadsides, railway embankments, wet meadows, utility corridors, and cultural woodland edges are also suitable for Colicroot but are not well characterized by ELC vegetation types

- the habitat is open ( 25% tree or shrub cover) and not shaded;

- the underlying ground is sand or sandy soil;

- the area immediately surrounding the plants is bare ground or predominantly covered with herbaceous plants, especially grasses, with some tallgrass prairie associates.

Suitable habitat in semi-naturalized areas ends where any of the following occur:

- the ground is entirely shaded by trees or shrubs (boundary is the forest edge);

- the soil is no longer sandy;

- there is active agricultural use (for crops or pasture) or manicured vegetation (lawns, gardens, etc.).

Although only a small portion of the suitable habitat area may be occupied, unoccupied area is required for wind dispersal, establishment, and expansion of the species to ensure long-term viability of the population at that site. Since Colicroot readily colonizes on disturbed (e.g. blowing or shifting) sandy soil (Kirk 1988) inclusion of additional areas surrounding the plants may accommodate the natural movement of sandy substrates and Colicroot colonies over time. In addition, suitable habitat requires periodic disturbance, so the extent of the suitable vegetation community is required to provide space for ecological processes that maintain habitat (such as fire, periodic flooding, etc.) to take place. As well, suitable natural habitat is extremely limited, so where the species occurs, it is important to protect all of the existing habitat.

Site occupancy

Site Occupancy Criterion: The site occupancy criterion defines an occupied site as a location where Colicroot has been observed for any single year since 1993 and where suitable habitat is present.

A site is defined by a boundary drawn at a distance of 50 m around a known observation of Colicroot. An observation may be represented by a point (representing a single plant or a location where there are multiple plants) or a polygon (collected as boundary points around the outer edge of a larger population). The 50 m distance is applied to each observation, with spatially overlapping areas merged together to form larger sites. In cases where observations are represented by a polygon, the 50 m distance is applied to the outer edge of the polygon.

Where Colicroot resides in natural habitat, the site boundary is extended beyond the 50 m to include the extent of continuous suitable habitat (ELC vegetation type, as described in Section 7.1.1), which is associated with, and is integral to, the production and maintenance of suitable habitat conditions and which provides the ecological context for occupied microhabitats. The entire suitable habitat patch is required to allow dispersal and establishment of the species. As well, suitable natural habitat is extremely limited, so where the species occurs, it is important to protect the entire existing habitat.

For populations in semi-naturalized habitats, the entire open area which may extend beyond the site boundary is not assumed to be suitable as some parts may not contain suitable habitat for Colicroot. Therefore, in semi-naturalized habitat only the area within the 50 m distance around a Colicroot plant is identified as an occupied site.

The 50 m distance is considered a minimum ‘critical function zone', or the threshold habitat fragment size required for maintaining constituent microhabitat properties for a species (e.g. critical light, moisture, humidity levels necessary for survival). At present, it is not clear at what distance physical and/or biological processes begin to negatively affect Colicroot. Studies on micro-environmental gradients at habitat edges, i.e., light, temperature, litter moisture (Matlack 1993), and of edge effects on plants in mixed hardwood forests, as evidenced by changes in plant community structure and composition (Fraver 1994), have shown that edge effects could be detected up to 50 m into habitat fragments. Forman and Alexander (1998) and Forman et al. (2003) found that most roadside edge effects on plants resulting from construction and repeated traffic have their greatest impact within the first 30 to 50 m. Therefore, a 50 m distance from any Colicroot plant is appropriate to ensure microhabitat properties for rare plant species occurrences are incorporated in the identification of critical habitat. The area within the site boundary may include both suitable and unsuitable habitat as Colicroot may be found near the transition area/zone between suitable and unsuitable habitat (e.g. within small forest openings, or along woodland edges).

Occupancy is determined using occurrence reports collected between 1993 and 2012. The 20-year timeframe is consistent with NatureServe’s (2002) and Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre’s (NHIC) threshold for considering populations to be extant versus historic, and allows for inclusion of a number of native populations that likely persist but which have not been recently surveyed. Given the known historic and current threats to the species, the assumption is that the species is extant until more information becomes available. Colicroot is a perennial species that may remain present in overgrown habitats for years without flowering. It can also seem to disappear for a few years until competing vegetation is removed, opening up the habitat (Woodliffe pers. comm. 2012). More detailed information on the location of critical habitat, to support protection of the species and its habitat, may be requested on a need-to-know basis by contacting Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service.

Including suitable habitat (determined using high resolution aerial photography to confirm its presence) in the occupancy criteria aims to protect sites where the plants are likely to still remain.

7.1.3 Application of the Colicroot critical habitat criteria

Critical habitat for Colicroot in Canada is identified as the sites containing suitable habitat (Section 7.1.1) and currently known to be occupied by Colicroot according to the site occupancy criteria (Section 7.1.2). For clarity, critical habitat includes all the habitat within a radial distance of up to 50 m from a Colicroot plant, where suitable habitat exists. In natural habitats, critical habitat also includes the entire ELC ecosite polygon described as suitable in Section 7.1.1.

Major roadways or built-up features such as buildings do not assist in the maintenance of natural processes and are therefore not identified as critical habitat. If a hard edge (e.g., major road, building) occurs within a site (e.g., prior to the 50 m distance), critical habitat ends at the hard edge.

In addition, some sites within the Ojibway Prairie Complex and LaSalle Woodlot ESA populations were partially within the Endangered Species Act, 2007permit boundary of the HGP development and are not currently identified as critical habitat. All plants previously occurring inside the HGP footprint have been transplanted into existing or restored suitable habitat. The majority of these restoration sites occur within the Ojibway Prairie Complex, LaSalle Woodlot ESA and surrounding areas. Additional plants were propagated and planted in the restoration sites. Once the transplanted populations occurring in suitable habitat have established the restoration sites will be reviewed and additional critical habitat may be identified.

For some Colicroot populations, little or no mapping and/or documentation of plant locations or habitat features exists, while for others, available data are more than 15 years old. For certain locations where Colicroot is confirmed to be extant (i.e. via pers. comm.) but no mapping exists, a generalized boundary is used to identify the area in which critical habitat is likely to occur. The generalized boundary is determined based on details provided in the observation (including historical references) and the extent of suitable habitat using air photo interpretation and recent imagery. Generalized boundaries of critical habitat were created at four sites (Ojibway Prairie Provincial Nature Reserve, Spring Garden Natural Area, "Ball Diamond" and Reaume Prairie ESA). Critical habitat at these sites reflects the best available information and may be refined as additional information becomes available.

Application of the critical habitat criteria to available information as of December 2012 identifies 15 sites (3 populations) as critical habitat for Colicroot in Canada (Appendix E). It is important to note that the coordinates provided are a cartographic representation of where the critical habitat sites can be found presented at the level of a 1 km x 1km grid and does not represent the extent or boundaries of the critical habitat itself. More detailed information on the location of critical habitat, to support protection of the species and its habitat, may be requested on a need-to-know basis by contacting Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service at ec.planificationduretablissement-recoveryplanning.ec@canada.ca.

The identification of critical habitat in this recovery strategy is based on the information currently available to Environment Canada for the 20-year time period of 1993-2012 and is insufficient to meet the population and distribution objectives, therefore a Schedule of Studies is included. As additional information becomes available, critical habitat identification may be refined or more sites meeting critical habitat criteria may be added.

Critical habitat is not identified for the two extant populations of Colicroot at Walpole Island First Nation. The information required to satisfy the critical habitat criteria (i.e., location and extent of populations, biophysical habitat attributes) is not available for use by Environment Canada. Although the continued presence of Colicroot has been confirmed (Jacobs pers. comm. 2010), confirming the extent of locations and biophysical habitat attributes (i.e., extent and amount of the ELC ecosite of suitable habitat (as listed in Section 7.1.1)) is also required for these populations. Once adequate information is available for use, additional critical habitat may be identified and may be described within an area-based multi-species at risk action plan developed in collaboration with the Walpole Island First Nation.

Critical habitat is not identified for two populations (Turkey Point and Eagle (SE of West Lorne)) and one subpopulation (West of Brunet Park) where the persistence of suitable habitat is not evident from recent imagery (high resolution orthophotography, circa. 2010). Confirmation of both species and suitable habitat persistence are required at these locations; this activity is described in the Schedule of Studies (Section 7.2).

In addition, the schedule of studies aims to confirm the location and extent of Colicroot population reports for five other locations of Colicroot considered to be of 'unknown' status (Table 1). The NHIC currently lists these locations as historic

The restoration sites for the HGP created under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 permit, are not currently identified as critical habitat. All plants previously occurring inside the HGP footprint have been transplanted into existing suitable habitat or restored habitat. The majority of these restoration sites occur within the Ojibway Prairie Complex, LaSalle Woodlot ESA and surrounding areas. Additional plants were propagated and planted in the restoration sites. Once the restoration plantings have established the HGP restoration sites will be reviewed and additional critical habitat may be identified.

Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

Table 4. Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

|

Description of Activity |

Rationale |

Timeline |

|---|---|---|

|

Confirm/obtain population information and conduct Ecological Land Classification for any outstanding natural populations/subpopulations. |

Location of population becomes known and habitat associations, biophysical habitat attributes and extent of suitable habitat are confirmed. |

2014-2019 |

|

Confirm/obtain population information and conduct habitat assessments (using ELC or other method to determine the boundaries of suitable habitat) for those populations/subpopulations with records older than 5 years (2008) and identify additional critical habitat. |

Location of population becomes known and habitat associations, biophysical habitat attributes and extent of suitable habitat are confirmed and critical habitat is fully identified. |

2014-2019 |

|

Confirm/obtain population and ELC information for HGP restoration sites and any other restoration planting sites and determine success of plantings and identify additional critical habitat. |

Locations of successful new or re-established populations becomes known and habitat associations, biophysical habitat attributes and extent of suitable habitat are confirmed, thereby allowing identification of critical habitat at these sites and fully identifying critical habitat. |

2014-2019 |

Activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

Understanding what constitutes destruction of critical habitat is necessary for the protection and management of critical habitat. Destruction of critical habitat is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat was degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from a single activity or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time. Activities described in Table 5 include those likely to cause destruction of critical habitat for the species; however; destructive activities are not limited to those listed.

Table 5. Activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

|

Description of Activity |

Description of Effect |

Details of Effect |

|---|---|---|

|

Development and conversion of lands (e.g. agricultural expansion, residential and commercial development, road construction) |

Results in loss of suitable substrate conditions, habitat fragmentation/increased edge effects and/or direct covering up of suitable ground Can reduce quality of germinating sites and/or prevent growth of Colicroot |

Direct effect, applicable at all times |

|

Operation of off road vehicles or removal of top soil (greater than a few centimetres) |

Results in ruts or trampled vegetation and loss of substrate or suitable substrate conditions These activities can reduce the quality of germinating sites and prevent establishment |

Repeated off road traffic will cause soil compaction, except when ground is frozen. Removal of topsoil is a direct effect at all times |

|

Fire suppression |

Results in expansion of woody vegetation in Colicroot habitat Increasing resource competition and habitat succession Creates unsuitable habitat conditions |

Long term fire suppression will result in shading or crowding out of the species |

|

Alteration of moisture levels (e.g. ditching, berm construction or tiling) |

Results in sites that are no longer moist but too wet or too dry Soil conditions are no longer suitable for Colicroot germination or growth |

A single event of this kind is very likely to result in destruction of critical habitat |

|

Introduction of invasive species (e.g. direct seeding or planting or through vectors such as ATVs) |

Results in increased resource competition through crowding or shading Can make habitat unsuitable for Colicroot |

A single event of this kind is likely to result in destruction of critical habitat |

|

Use of herbicides, constant mowing, livestock grazing, tree planting, depositing fill |

Results in alteration of soil conditions and/or light intensity rendering habitat unsuitable for growth of Colicroot Can result in loss of native species and degradation of critical habitat |

Even localized impacts by these activities can change soil and light conditions affecting the species |

Measuring progress

The performance indicators presented below provide a way to define and measure progress toward achieving the population and distribution objectives.

Every five years, success of recovery strategy implementation will be measured against the following performance indicators:

- the abundance of each extant population of Colicroot in Canada has been maintained at its current level or has increased;

- there are at least five extant populations of Colicroot across its native range in Canada.

Statement on action plans

One or more action plans for Colicroot will be completed by December 2021.

References

Ambrose, J. D., and G. E. Waldron. 2005. Draft National Recovery Strategy for Tallgrass Communities of southern Ontario and their associated species at risk. Draft recovery plan prepared for the Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario Recovery Team. National Recovery Plan, Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW), Ottawa, Ontario.

AMEC Environment and Infrastructure, environmental consultants on behalf of the Parkway Infrastructure Constructors and Windsor Essex Mobility Group. 2013. 2012 Annual Monitoring Report for Plant Species at Risk The Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway Volume 1 Mitigation and Monitoring Created To Meet the Conditions of Endangered Species Act (2007) Permits AY-B-009-04; AY-C-009-01; AY-D-001-09; and AY-C-004-11. 147 pp.

Argus, G.W., K.M. Pryer, D.J. White, and C.J. Keddy. 1982-87. Atlas of the Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario. 4 parts. National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa, Ontario.

Bakowsky, W.D. and J.L. Riley. 1994. A survey of the prairies and savannas of southern Ontario. Proceedings of the Thirteenth North America Prairie Conference: 7-16. Edited by R.G. Wickett, P.D. Lewis, A. Woodliffe, and P. Pratt.

Bowles, Jane, personal communication. 2010. Curator of herbarium, University of Western Ontario, London; and consulting ecologist.

Bowles, J.M. 2005. Draft Walpole Island Ecosystem Recovery Strategy. Walpole Island Heritage Centre, Environment Canada, and the Walpole Island Recovery Team.

COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the colicroot Aletris farinosa in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 10 pp.

COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the pink milkwort Polygala incarnata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 24 pp.

Cronquist, A. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, 2nd ed. New York Botanical Garden, 910 pp.

Environment Canada. 2010. Species at Risk Public Registry. Species Profile: Colicroot. Web site: http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=214 [accessed June 09, 2011].

Forman, R.T.T. and L. E. Alexander. 1998. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29:207-231.

Forman, R. T. T., D. Sperling, J. A. Bissonette, A. P Clevenger, C. D. Cutshall, V. H. Dale, L. Fahrig, R. France, C. R. Goldman, K. Heanue, J. A. Jones, F. J. Swanson, T. Turrentine, and T. C. Winter. 2003. Road ecology: science and solutions. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

Fraver, S. 1994. Vegetation Responses along Edge‐to‐Interior Gradients in the Mixed Hardwood Forests of the Roanoke River Basin, North Carolina. Conservation Biology 8(3): 822-832.

Harris, A. 2009. Mitigation Methods for Vascular Plant Species at Risk in Ontario. Northern Bioscience, unpublished report.

Jacobs, C. 2011. Bkejwanong’s Conservation Approaches: Completing the Circle. Walpole Island Heritage Centre, https://secure.nalma.ca/file/3cb658835977.pdf Accessed January 11, 2013.

Jacobs, Clint, personal communications. 2010 and 2013. Natural Heritage Coordinator, Walpole Island Heritage Centre.

Jones, J. 2013. Draft Recovery strategy for the Willowleaf Aster (Symphyotrichum praealtum) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 23 pp.

Kirk, D.A. 1987. Conservation Recommendations for Colicroot, Aletris farinosa L., a Threatened Species in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), Ontario. 5 pp.

Kirk, D.A. 1988. Status Report on the Colicroot, Aletris farinosa, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 39 pp.

Kirk, Donald, personal communication. 2011. Natural Heritage Ecologist, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Guelph District.

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. "Mesic Sand Prairie" in Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI. http://web4.msue.msu.edu/mnfi/communities/community.cfm?id=1069 accessed January 13, 2011.

Lee, H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application. OMNR, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch. SCSS Field Guide FG-02. 225 pp.

Lee, Harold, personal communication. 2012. Ecologist, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, London, Ontario.

LGL Limited. 2013. Draft Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) Trials 2012 Annual Monitoring Report The Windsor-Essex Parkway Created To Meet Conditions of Permit No. AY-D-001-09 Issued Under the Authority of Clause 17(2)(d) of the Endangered Species Act, 2007. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation, London, Ontario. 61 pp.

NatureServe. 2012. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopaedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available at http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed: December 20, 2012).

Matlack, G. R. 1993. Microenvironment variation within and among forest edge sites in the eastern United States. Biological conservation 66(3), 185-194.

NHIC. 2011. Electronic and element occurrence databases. http://nhic.mnr.gov.on.ca/nhic.cfm (accessed December, 2011).

Oldham, M.J. 2000. Element Occurrence records of White-tubed Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) from the database of the Natural Heritage Information Centre, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough. 30 pp.

Oldham, Mike, personal communication. 2013. Botanist/Herpetologist, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Natural Heritage Information Centre.

Tallgrass Ontario. 2005. A Landowner’s Guide to Tallgrass Prairie and Savanna Management in Ontario, Tallgrass Ontario. i + 48 pp.

Pratt, Paul, personal communication. 2010. Naturalist, Ojibway Park Nature Centre, City of Windsor.

Waldron, Gerry, personal communication. 2010. Consulting Ecologist, Amherstberg, Ontario.

White, D.J., and M.J. Oldham. 2000. Update COSEWIC status report on the Colicroot Aletris farinosa in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 8 pp.

Woodliffe, Allen, personal communication. 2010. District Ecologist, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aylmer District, Chatham, Ontario.

Appendix A: Effects on the environment and other species

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts upon non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into the strategy itself, but are also summarized below in this statement.

Many at-risk and rare species occur in tallgrass prairie habitats. Therefore, it is expected that recovery efforts for Colicroot will also benefit many other species that occur in these habitats and could be conducted in combination with recovery activities for other species such as Dense Blazing Star, Willowleaf Aster and many others (Table 6). Habitat securement, policy, and stewardship approaches are not expected to have adverse effects on the habitat.

Prescribed burning can improve habitat for many rare and at-risk tallgrass prairie species, but burning may also harm some species sensitive to fire. However, fire is recognized as an integral part of this ecosystem and has been used by First Nations people as a management tool for millennia. Therefore, it is intended that any reduction of species sensitive to fire should still result in population levels that fall within the natural range of fluctuations. Monitoring to determine the effects of fire on some species may be necessary. Fire may reduce the presence of woody species to the benefit of tallgrass prairie species. This is not expected to have a significant impact since the encroaching woody species are often common in other habitat types.

Table 6. Species expected to benefit from recovery techniques directed at Colicroot in Canada

|

Common Name |

Scientific (Latin) Name |

SARA Status |

|---|---|---|

|

Climbing Prairie Rose |

Rosa setigera |

Special Concern |

|

Monarch |

Danaus plexippus |

Special Concern |

|

Riddell’s Goldenrod |

Solidago riddellii |

Special Concern |

|

Butler’s Gartersnake |

Thamnophis butleri |

Threatened |

|

Dense Blazing Star |

Liatris spicata |

Threatened |

|

Massasauga |

Sistrurus catenatus |

Threatened |

|

Willowleaf Aster |

Symphyotrichum praealtum |

Threatened |

|

Eastern Foxsnake |

Pantherophis gloydi |

Endangered |

|

Eastern Prairie Fringed-Orchid |

Platanthera leucophaea |

Endangered |

|

Gattinger’s Agalinis |

Agalinis gattingeri |

Endangered |

|

Henslow’s Sparrow |

Ammodramus henslowii |

Endangered |

|

Northern Bobwhite |

Colinus virginianus |

Endangered |

|

Pink Milkwort |

Polygala incarnata |

Endangered |

|

Purple Twayblade |

Liparis liliifolia |

Endangered |

|

Skinner’s Agalinis |

Agalinisskinneriana |

Endangered |

|

Slender Bush-clover |

Lespedeza virginica |

Endangered |

|

Small White Lady’s-slipper |

Cypripedium candidium |

Endangered |

Appendix B: Extirpated populations of Colicroot

Table 7. Sites where Colicroot is presumed extirpated (source: NHIC 2011)

|

County |

Populations (or subpopulations) |

Last Obs. |

Status |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Elgin |

West Lorne Woods |

1986 |

Extirpated |

Extirpation most likely due to natural succession of poplar (Populus sp.), raspberry (Rubus sp.), and sassafras (Sassafras albidum). |

|