Gillman’s Goldenrod recovery strategy

Read the recovery strategy for Gillman’s Goldenrod, a plant at risk in Ontario.

Cover illustration: Photo by John Semple

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Catling, P.K., D.A. Bettencourt and W.D. Van Hemessen. 2022. Recovery Strategy for the Gillman’s Goldenrod (Solidago gillmanii) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 39 pp.

Cover illustration: Photo by John Semple

© King’s Printer for Ontario, 2022

ISBN 978-1-4868-6199-6 9 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4868-6200-9 (PDF)

Content (excluding illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@ontario.ca.

Authors

Pauline Kimberley Catling – North-South Environmental Inc., Cambridge, Ontario

Devin Anne Bettencourt – North-South Environmental Inc., Cambridge, Ontario

William Douglas Van Hemessen – North-South Environmental Inc. Cambridge, Ontario

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people and agencies for sharing their expertise and knowledge: Judith Jones, John Semple, Wasyl Bakowsky, Sam Brinker, Jess Peirson, The Nature Conservancy, The Nature Conservancy of Canada, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Michigan Natural Features Inventory (Michigan State University) and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Gillman’s Goldenrod (Solidago gillmanii) was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The recommended goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks,

Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

Gillman’s Goldenrod (Solidago gillmanii) is listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007. This species has No Status under the Federal Species at Risk Act, 2002, but it is under consideration for addition to Schedule 1. It has a global rank of G5T3? (Globally Secure with the infraspecific taxon being Globally Vulnerable) and a subnational rank of S1 (Critically Imperiled) in Ontario. A Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) status report was published for the species in 2019.

Gillman’s Goldenrod is a perennial plant in the Aster Family (Asteraceae). The species is robust and grows between 20 to 120 cm tall. Flowering occurs in late August to early October. It produces an upright wand-like inflorescence of bright yellow flowers. Gillman’s Goldenrod is very similar to Hairy Goldenrod (S. hispida) and Bog Goldenrod (S. uliginosa), which overlap in habitat.

Gillman’s Goldenrod is endemic to dune shorelines of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. There are two extant subpopulations of Gillman’s Goldenrod in Canada, all within Ontario in the Manitoulin Island region. Both subpopulations are on a single parcel of privately owned land that is under land claim by First Nations.

In Ontario, Gillman’s Goldenrod is currently restricted to dune habitats along the shorelines of Great Duck Island. Historically, this species was also located at Deans Bay on Manitoulin Island; however, that occurrence was extirpated prior to 2000. Suitable habitat falls into one vegetation community type, Little Bluestem – Long-leaved Reed Grass – Great Lakes Wheat Grass Dune Grassland, which is provincially imperiled (S2) in Ontario. Gillman’s Goldenrod typically grows on open sand dune with sparse vegetation and exposed sand.

There are many knowledge gaps for Gillman’s Goldenrod including population trends, population viability levels, the effects of current threats, habitat and microhabitat requirements, genetics and techniques for reintroductions. Additional knowledge gaps include site-specific habitat dynamics and potential effects of climate change.

The primary threat to Gillman’s Goldenrod is invasion by non-native species, Glandular Baby’s-breath (Gypsophila scorzonerifolia) and European Reed (Phragmites australis australis), which may prevent establishment of new Gillman’s Goldenrod individuals through competition and promote habitat succession, reducing habitat suitability. All other threats are considered negligible or uncertain. The threat of climate change is considered to be negligible; however, the impact is uncertain as climate change could alter dune dynamics and has the potential to increase the amount of suitable habitat or decrease it.

A vital aspect for recovery of Gillman’s Goldenrod is to complete studies that monitor population trends and assess the viability of each subpopulation. Until further information regarding population viability is available, the recommended recovery goal for Gillman’s Goldenrod is to maintain the current abundance and distribution of both subpopulations in Ontario. Once an effective population size for each subpopulation has been determined, the recommended recovery goal should be to increase or maintain subpopulation size and distribution to viable levels.

Population augmentation is not necessary at this time; however, further population monitoring is recommended to ensure the populations remain stable over time Increasing our knowledge of the species’ biology will be vital if augmentation becomes necessary in the future. Recommended protection and recovery objectives include:

- assess threats and undertake actions to eliminate them or reduce the severity of their impact

- protect and maintain Gillman’s Goldenrod habitat using policy and legislative tools, where appropriate

- raise awareness about Gillman’s Goldenrod and its habitat

- fill knowledge gaps

A variety of recovery approaches are described in the text.

The area recommended to be considered for inclusion in a habitat regulation for Gillman’s Goldenrod includes:

- all areas where Gillman’s Goldenrod is present and any new areas that are discovered

- the entire Ecological Land Classification (ELC) Community Class in which Gillman’s Goldenrod is present

- the complete beach-dune system in which Gillman’s Goldenrod is present from the low water mark of the lake shore to the belt of mature vegetation behind the dunes in order to protect the dynamics of the dunes and allow for constant natural changes

- all of the terrestrial area within a distance of 15 m from the ELC Community Class in which Gillman’s Goldenrod occurs, including unsuitable habitat

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

The following list is assessment and classification information for the Gillman’s Goldenrod (Solidago gillmanii).

- SARO List Classification: Endangered

- SARO List History: Endangered (2021)

- COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2019)

- SARA Schedule 1: No Status (Under consideration)

- Conservation Status Rankings: G-rank: G5T3?; N-rank: N1; S-rank: S1.

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations and ranks above and for other technical terms in this document.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Gillman’s Goldenrod (Figure 1) is an herbaceous perennial plant species in the Aster Family (Asteraceae). Gillman’s Goldenrod was previously considered a variety or subspecies of several different goldenrod species (VASCAN 2020; Semple and Peirson 2013), but further work has led to the recognition of this taxon as a distinct species, which is tetraploid (COSEWIC 2019; Peirson et al. 2012; Steele 1911).

Gillman’s Goldenrod is a robust plant growing between 20 to 120 cm tall (COSEWIC 2019; Semple and Cook 2006). Flowers bloom from late August to early October. As with all members of the Aster Family, what appear to be flowers are actually composite heads of individual florets, including ray florets and disc florets. In Gillman’s Goldenrod, both the ray florets (pistillate) and the disc florets (bisexual) are bright yellow. The inflorescence of Gillman’s Goldenrod has heads in paniculiform arrays, which give it an upright wand-shaped appearance (COSEWIC 2019; Semple and Cook 2006). The flowering heads are large (6 to 9 mm tall by 5 to 10 mm wide) compared to other goldenrods (COSEWIC 2019). The florets develop into one-seeded cypselae (fruit derived from inferior ovary) with a pappus at the top (COSEWIC 2019). Cypselae are sparsely strigose near the point of attachment and sparsely to moderately dense strigose at the other end (Semple 2018).

The basal leaves are spatulate (with broad rounded ends) to obovate (roughly egg-shaped with the narrower end at the base), 15 to 30 cm long, with leaf margins dentate (with teeth directed outward rather than forwards), serrate (with teeth pointing forwards) or crenate (round-toothed or scalloped) and an acute tip (Semple and Cook 2006). Lower stem leaves are sharply serrate (Semple 2018). Leaves decrease in size upwards along the stem with cauline leaves ranging from 7 to 47 cm long (COSEWIC 2019; Michigan Flora Online 2011; Semple and Cook 2006). The leaves and involucres are resinous (Michigan Flora Online 2011).

Gillman’s Goldenrod is visually similar to Hairy Goldenrod (S. hispida), Ontario Goldenrod (S. ontarioensis) and Bog Goldenrod (S. uliginosa) (COSEWIC 2019; Michigan Flora Online 2011). Gillman’s Goldenrod can be distinguished from Hairy Goldenrod by having resinous leaves and phyllaries, appressed cauline leaves and fruits that are slightly to densely hairy with hairs pointing upwards towards the pappus (COSEWIC 2019; Michigan Flora Online 2011; Semple and Cook 2006). It can be distinguished from Ontario Goldenrod by having large, wide (10 to 42 mm) leaves with serrate margins rather than narrow (2 to 20 mm) leaves with crenate or slightly toothed margins (COSEWIC 2019; Semple and Cook 2006). It can be distinguished from Bog Goldenrod by the absence of sheathing leaves (COSEWIC 2019). Hairy Goldenrod and Bog Goldenrod may occur in the same habitat as Gillman’s Goldenrod, but Ontario Goldenrod occurs only on rocks (COSEWIC 2019).

Figure 1. Gillman's Goldenrod (photo by John Semple).

Species biology

Gillman’s Goldenrod is a perennial herb that grows from a single rhizome. Plants first appear as a basal rosette or cluster of rosettes. The horizontal rhizome allows a plant to grow upward as it is buried by sand and elongated rhizomes are present even in seedlings (J. Peirson pers. com. 2021).

Plants may be sterile (not producing flowers) for one to several years after germination and plants may not flower every year even after they mature (COSEWIC 2019). Not much is known about the age of plants at maturity, the trigger for flowering, lifespan, pollinator species, pollination success, seed set, seed viability and germination requirements of Gillman’s Goldenrod. Goldenrod species are thought to live for a decade or more, so the estimated generation time for Gillman’s Goldenrod is assumed to be between five and fifteen years (COSEWIC 2010; Jones 2015; COSEWIC 2019).

Although it is rhizomatous, Gillman’s Goldenrod primarily reproduces by seed and does not produce large colonies or clones (COSEWIC 2019). It is assumed that, like other goldenrods, cross-pollination is required for successful seed set (COSEWIC 2019; Buchele et al. 1992; Gross and Werner 1983; Werner et al. 1980). Specific pollinators of Gillman’s Goldenrod are unknown, but it is assumed to be pollinated by a variety of insect species. Goldenrods have heavy, sticky pollen that is solely dispersed by insects such as bees, wasps, flies, moths and butterflies (Buchele et al. 1992; COSEWIC 2005; COSEWIC 2010; COSEWIC 2019; Semple et al. 1999). Pollen transfer may be a limitation to successful sexual reproduction of Gillman’s Goldenrod (COSEWIC 2019).

Goldenrods have tiny, dry, single-seeded fruits that are mainly wind-dispersed with assistance of the pappus bristles present on the top of the fruit. The dispersal distance of goldenrod fruit is unknown. Dispersal distance by wind may be variable and dependent on wind speed, weather, humidity, inflorescence height, plume-loading (the ratio of the falling seed’s mass to its area), and the height of the surrounding vegetation (Soons et al. 2004). Long-distance dispersal of plants in the Aster Family is uncommon and would require convection currents to carry fruit high up in the air (COSEWIC 2019; Sheldon and Burrows 1973). Research on wind dispersal of grassland plant species has found that seeds rarely disperse beyond 100 m from the parent plant and this limitation is expected to apply to seeds of Gillman’s Goldenrod (Tackenberg et al. 2003). However, Gillman’s Goldenrod is expected to have a fairly high dispersal distance compared to other wind-dispersed plants due to its tall inflorescence, preference for open sites and small fruit size. Incidental movement of Gillman’s Goldenrod seeds by birds may be the only potential for long-distance dispersal mechanism. Avian dispersal of goldenrods has been noted previously by Czarnecka et al. (2012). However, Gillman’s Goldenrod sets fruit in fall and northward bird migration or local bird movements would be required to disperse seeds to the nearest suitable habitats. The potential for avian dispersal to other locations in Ontario unlikely. Other goldenrod species have been noted to have low fruit set and germinability and are not long-lived (i.e., seeds remain viable for only one year) in the seed bank (Jones 2015).

Gillman’s Goldenrod is adapted to dune habitats and is tolerant of shifting substrate and the harsh conditions on dunes (e.g., high wind, high heat, high light levels, seasonal flooding and drought). The long vertical rhizomes of Gillman’s Goldenrod may contribute to its resistance to sand burial, shifting substrates and low soil moisture levels (COSEWIC 2019).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Gillman’s Goldenrod is endemic to dune shorelines of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron (Semple 2018; COSEWIC 2019; COSARO 2020). It is more common on dunes on Lake Michigan than on Lake Huron (COSEWIC 2019). The increased abundance on Lake Michigan is potentially due to the westerly winds forming large dunes along the eastern and southern shorelines (Cowles 1899), which have created a large area of suitable habitat. In the United States, Gillman’s Goldenrod occurs in Michigan, Wisconsin and Indiana, with an unconfirmed record from Illinois (Kartesz 2015).

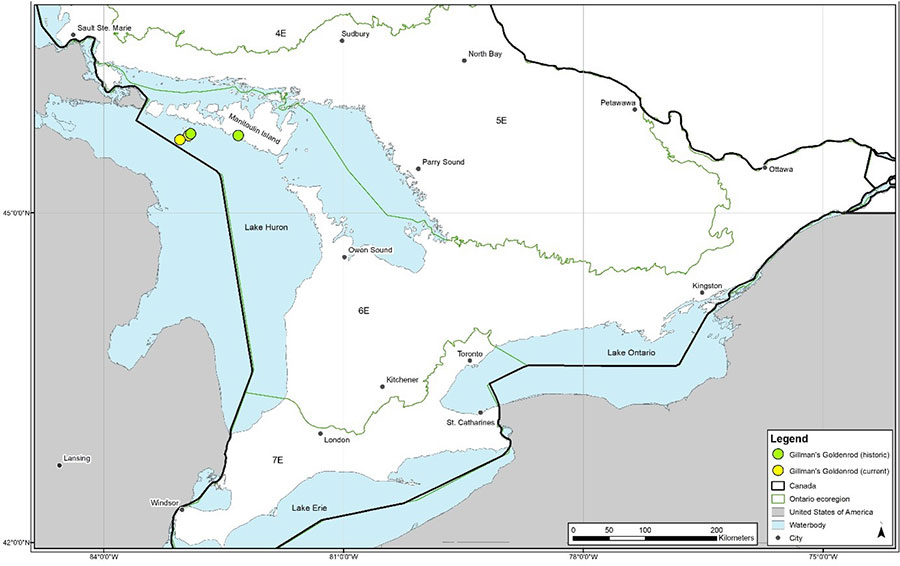

In Canada, Gillman’s Goldenrod only occurs in Ontario on Great Duck Island, which is located 16 km south of Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron (Figure 2). The entire Ontario population occurs within ecoregion 6E (Figure 2). Two subpopulations occur on Great Duck Island, at Desert Point and Horseshoe Bay, which are 2.5 km apart. A 1976 collection from Deans Bay on Manitoulin Island indicates that this species was historically present elsewhere in Ontario (Figure 2). However, there is some suggestion that the specimen may have been collected from Great Duck Island and its location mis-recorded on the specimen (J. Jones pers. com. 2021). If it was present, Gillman’s Goldenrod was extirpated from Deans Bay prior to 2000 (cottage development has occured in that area) and there are no recent records of this species from anywhere beyond Great Duck Island. Subpopulations in Ontario are summarized in Table 1.

Targeted surveys at 30 apparently suitable dune sites across the southern shorelines of Manitoulin, Western Duck and Cockburn Islands have failed to detect Gillman’s Goldenrod (COSEWIC 2019). There are other sand dunes and beaches on the eastern shore of Lake Huron (Chapman and Putnam 1984) as well as the northern shoreline of Manitoulin Island, but these areas are expected to be unsuitable for Gillman’s Goldenrod due to the acidic nature of the sand and/or site-specific differences in dune dynamics (W. Bakowsky pers. comm. 2021); however, these factors have not been officially studied and the site-specific differences are unknown.

In 2018, abundance estimates for Gillman’s Goldenrod at Desert Point were 5,000 individuals. Estimates at Horseshoe Bay were approximately 1,500 individuals (COSEWIC 2019). Horseshoe Bay contains about 1.65 ha of suitable habitat, while Desert Point contains about 27.3 ha of dune with 17 ha being suitable for Gillman’s Goldenrod (COSEWIC 2019). Prior to fieldwork undertaken for the preparation of the COSEWIC status report, no quantitative estimates of abundance were recorded, but Gillman’s Goldenrod was noted to be common at both locations from 2000 to 2018. No major changes to the habitat have occurred between 2004 and 2018 (COSEWIC 2019). Historical abundance at Deans Bay is unknown but it is assumed to have been less abundant at that location (COSEWIC 2019). With the exception of Deans Bay, Gillman’s Goldenrod has not undergone extreme fluctuations in abundance or distribution in the past 18 years, but a population decline of uncertain severity is projected due to invasion by non-native plant species (COSEWIC 2019). Declines are thought to be reversible (COSEWIC 2019).

Great Duck Island is located in the unorganized part of the District of Manitoulin and outside of the Manitoulin Planning Area and therefore occurrences at Horseshoe Bay and Desert Point do not fall under any municipal jurisdiction (see Schedule B and D of the Manitoulin Region Official Plan 2018). Deans Bay also occurs within the unorganized part of the District of Manitoulin but falls within the Manitoulin Planning Area. In Manitoulin region, the shoreline area below the surveyed historical high-water mark is municipal jurisdiction. Therefore, part of the shoreline and dune habitat at Deans Bay would be in municipal jurisdiction. However, this does not apply to either site where the species is extant currently.

Great Duck Island is a single parcel of privately-owned land (COSEWIC 2019). All islands surrounding Manitoulin Island, including Great Duck Island, are under land claim by Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory (WUT) (COSEWIC 2019). Great Duck Island is classified as a Provincially Significant Life Science Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI) (NHIC 2021a).

Figure 2. Historical and current distribution of the Gillman’s Goldenrod in Ontario. Occurrence locations are generalized and represented by white (historic: over 30 years ago) and black (current: within the last 30 years) dots (NHIC 2021b).

| Site Name | Ownership | Estimated abundance | Estimated habitat area (ha) | Most recent observation and observer | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desert Point | Private | 5000 | 27.3 | 2018 J. Jones (Extant) |

Under land claim by WUT |

| Horseshoe Bay | Private | 1500 | 1.7 | 2018 J. Jones (Extant) |

Under land claim by WUT |

| Deans Bay | Municipal/ Private | unknown | 1.9 | 1976 G. Ringus and J. Wilson (Historic/ Extirpated) |

Record from a collection housed in the University of Waterloo Herbarium (WAT); ID 228067 |

Note. All sites occur within the unorganized part of Manitoulin District.

1.4 Habitat needs

In Ontario, Gillman’s Goldenrod is found exclusively on open sand dunes with sparse vegetation. Based on the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) system for Southern Ontario (Lee et al. 1998), the vegetation community that supports habitat for Gillman’s Goldenrod is Little Bluestem – Long-leaved Reed Grass – Great Lakes Wheat Grass Dune Grassland (SDO1-2).

Locations where Gillman’s Goldenrod occur are dominated by dune grasses, such as Marram Grass (Calamagrostis breviligulata subsp. breviligulata), Great Lakes Wheat Grass (Elymus lanceolatus ssp. psammophilus), and Giant Sand Reed (Sporobolus rigidus var. magnus), shrubs, such as Common Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), Common Juniper (Juniperus communis), Creeping Juniper (Juniperus horizontalis), and Prostrate Sand Cherry (Prunus pumila var. depressa), and sparse trees, such as Tamarack (Larix laricina), White Spruce (Picea glauca), and Balsam Poplar (Populus balsamifera) (COSEWIC 2019; Morton and Venn 2000). Additional species that are present on the calcareous dunes in the Manitoulin Region include Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardi), Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), Indian Grass (Sorghastrum nutans), Tall Wormwood (Artemisia campestris subsp. caudata), Golden Puccoon (Lithospermum carolinienese) and Sand Dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus) (Bakowsky and Henson 2014).

The dunes are typically more open and graminoid-dominated closer to the shoreline and become increasingly wooded towards the interior (COSEWIC 2019). The habitat characteristics of Gillman’s Goldenrod overlap considerably with those of the provincially threatened Pitcher’s Thistle (Cirsium pitcheri), with which it can co-occur (COSEWIC 2000; OMNR 2013).

Disturbance that maintains openness of the dune habitat is thought to improve growing conditions for Gillman’s Goldenrod. Natural habitat dynamics are necessary to maintain openness and prevent the inland parts of the dunes from becoming densely vegetated (COSEWIC 2019).

The sands which make up beaches and dunes on Great Duck Island and the southern shore of Manitoulin Island are primarily calcareous (Bakowsky and Henson 2014; W. Bakowsky pers. comm. 2021). Dune types present in this area include bayhead beach dunes and barrier dunes, which may be comprised of transverse dunes, parabolic dunes, cliff dunes and blowouts (Bakowsky and Henson 2014; Davidson 1990; Martini 1981). Desert Point has been described as a foreland dune (130 ha), which characteristically are dunes associated with old beaches that include small to large areas with low forelands, continuous foredunes and wetlands (Davidson 1990). Horseshoe Bay (20 ha) has been characterized as a big bay dune, which are characteristically large bays curved to the shape of a bow with continuous foredunes, high secondary dunes, low interdune areas and parabolic forms up to 30 m high (Davidson 1990).

Little is known about the habitat requirements of Gillman’s Goldenrod in terms of dune types, but Ontario occurrences are on calcareous foreland dunes (W. Bakowsky pers. comm. 2021). At Desert Point, a continuous foredune is followed by sequences of inland dunes reaching 6 to 8 m in height and separated by broad, flat, wind deflated pannes (Davidson 1990). At Horseshoe Bay, the active zone consists of a foredune followed by two secondary dune ridges reaching heights of 12 m followed by a fourth larger dune ridge that has become more densely vegetated (Davidson 1990).

1.5 Limiting factors

Succession

Natural succession has been identified as a threat to other dune species at Horseshoe Bay (OMNR 2013). Succession may involve the natural encroachment of woody vegetation, which stabilizes the dunes and may out-compete or make the habitat less ideal for Gillman’s Goldenrod. It is uncertain what the extent and severity of this threat may be because natural succession, blowout and dune deposition are normal parts of dune dynamics. Succession may cause temporary declines or population fluctuations but succession by native species is expected to be a negligible threat. Dune dynamics naturally would be expected to maintain a portion of open habitat where Gillman’s Goldenrod may persist. The impact of accelerated succession due to climate change altered water levels may occur; however, the potential for and severity of accelerated succession is uncertain. Succession by non-native species may be facilitated by artificial stabilization of dunes (S. Mainguy pers. comm. 2022).

Reproduction

No information is available on seed germinability, fruit set, self-infertility and pollen transfer rate. These natural limitations may affect Gillman’s Goldenrod subpopulations and the ability to recover this species. The impacts of these factors cannot be assessed fully. Additionally, due to the late blooming nature of Gillman’s Goldenrod, early frost may prevent successful pollination in some years. These limiting factors may compound with the effects of threats outlined in Section 1.6.

Dispersal to suitable habitat is also expected to be a limiting factor. The distance to other suitable habitats beyond the extant occurrences of Gillman’s Goldenrod on Great Duck Island (e.g., 9 km to Western Duck Island; 16 km to Manitoulin Island) is likely too far for wind-dispersal to occur (COSEWIC 2019). Other species of wind-dispersed seeds have been found to survive floating on water for up to a week (Carthey et al. 2016).

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

The primary threat to Gillman’s Goldenrod on Great Duck Island is non-native plant species. The potential threats posed by climate change are largely uncertain but shifting weather and climate patterns on Lake Huron dune shorelines may facilitate invasion of non-native plant species. Other threats detailed below are not expected to have a large impact on existing subpopulations but may impact the ability to introduce or reintroduce Gillman’s Goldenrod at historic locations or other areas of suitable habitat.

Invasion by non-native plant species

Glandular Baby’s-breath (Gypsophila scorzonerifolia), European Reed (Phragmites australis australis) and other non-native plant species pose the greatest threat to Gillman’s Goldenrod and its habitat in Ontario (COSARO 2020). These species colonize quickly and are difficult to eradicate making them a particular threat to native dune ecosystems. Both Glandular Baby’s-breath and European Reed have been detected at Horseshoe Bay. European Reed has been removed from the area by the Manitoulin Phragmites Project, but it could re-invade there in the absence of ongoing stewardship and management. Glandular Baby’s-breath is considered established at Horseshoe Bay and to date no stewardship actions have been taken to manage it (COSEWIC 2019). In Michigan, Common Baby’s-breath (G. paniculata), which is closely related to Glandular Baby’s-breath, has invaded dune habitats, altering soil nutrients and properties (COSEWIC 2019; Emery et al. 2013). Although mature Gillman’s Goldenrod and other dune species are able to coexist with Glandular Baby’s-breath, these invasive species can reduce the area of open sand which may affect the establishment of Gillman’s Goldenrod seedlings, making the long-term impact of this species less obvious (COSEWIC 2019).

Other non-native species such as White Sweet-clover (Melilotus albus), Yellow Sweetclover (M. officinalis), knapweeds (Centaurea spp.), Leafy Spurge (Euphorbia virgata), Giant Knotweed (Reynoutria sachalinensis) and White Poplar (Populus alba) occur on Lake Huron shorelines and may invade dune habitats or encroach from adjacent habitats. These non-native species have been noted to impact dune ecosystems in Michigan where knapweeds and Glandular Baby’s-breath are a particular concern because of long-lived seedbanks (Albert 2000; Nature Conservancy 2015). Recovery activities in Michigan and Wisconsin have focused on control of Common Baby’s-breath, European Reed, knapweeds, European Lyme Grass (Leymus arenarius), Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica), Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) and Bladder Campion (Silene vulgaris) (J. Koebernik pers. com. 2021; J. Lincoln pers. com. 2021; Nature Conservancy 2015). Invasive species may limit the success of establishment in other areas of suitable habitat in Manitoulin District.

Secondary invasion by other non-native species following removal of a target non-native species is a potential outcome of invasive species management (Emery et al. 2013).

Climate change and changes in lake levels may increase the severity of the threat posed by invasive species.

Climate change and severe weather

Many aspects of climate and weather influence dune dynamics including wind, winter temperatures (that freeze the shoreline and reduce erosion) and water level (Albert 2000). Dune dynamics may be affected by climate change as it influences these factors, but the extent of impacts that climate change may have on Gillman’s Goldenrod and its habitat are uncertain (COSEWIC 2019). Higher water levels accelerate dune expansion through wave erosion causing deposition of greater amounts of sand and other sediments (Albert 2000). Dune expansion increases the available habitat for open dune species in the long-term. Increased erosion and sand movement can also bury or scour vegetation species not specific to dune habitats and not well-adapted to sand dynamics, reducing succession (Albert 2000). Alternatively, high water levels may flood lower portions of the dune, making these areas unsuitable for certain species. Low water levels are expected to promote natural succession and allow forests or thickets to establish, reducing the available habitat long-term (Albert 2000). Projections for Lake Huron suggest a lowering of lake levels by one or two metres (Peach 2006). Extreme high lake levels in the mid-1980s may have contributed to the extirpation of Gillman’s Goldenrod at Deans Bay since the already narrow dunes were subject to heavy wave wash (COSEWIC 2019). Existing climate change projections are on a global scale and may be inaccurate at predicting local precipitation and evapotranspiration and thus the effects on lake water levels (Davidson-Arnott 2016).

Some potential impacts of climate change to Lake Huron were described by Davidson-Arnott (2016) including:

- an increase in temperature causing a significant decrease in the extent and duration of winter ice cover on the lake that also has the potential to increase evaporation from the lake

- increase in precipitation amount but with a decrease in the amount of precipitation that falls as snow and an increase in number of heavy downpour events

- increased wind speeds and an increased number of storm events

Recreational activities

Despite being dynamic ecosystems, dunes are fragile features and human activities without periods of recovery can rapidly degrade them (Peach 2006). Great Duck Island is remote and only accessible by water. Threats from recreational use by boaters, including kayakers, are therefore small in scope and negligible in severity but are expected to be ongoing. Threats from recreational usage largely come from firepits, tenting and foot traffic, which damages vegetation (COSEWIC 2019; Peach 2006). Off-road vehicle use has been identified as a significant threat in the United States (S. Howard and K. Kearns pers. com. 2021), but this is not expected to occur in Canada due to the remote nature of Great Duck Island. Recreational use may also introduce invasive non-native species. Overall, recreational activities at the current levels are expected to have a negligible impact on extant subpopulations (COSEWIC 2019).

Impacts from ongoing recreational activities should be considered prior to introducing Gillman’s Goldenrod to historical locations or other areas of suitable habitat.

Development and construction

Development is unlikely to occur on Great Duck Island because it is remote, only accessible by water, has no residents and no roads. Development and construction are not expected to pose a threat to existing subpopulations over the next ten years (COSEWIC 2019). However, due to the private landownership of Great Duck Island, this potential threat should not be dismissed.

Development and construction of cottages at Deans Bay may have contributed to the extirpation of Gillman’s Goldenrod in that location (COSEWIC 2019). Cottages have been present since the mid-1960s and impacts to Gillman’s Goldenrod could have been directly or indirectly related to development. Many landowners at Deans Bay clear vegetation on the dunes, which could have contributed to the extirpation of a subpopulation that is presumed to have never been highly abundant. The potential for reintroduction to Deans Bay may be limited by ongoing anthropogenic impacts associated with existing cottages as well as the potential for development of additional cottages. It is expected that additional development and construction is likely to occur in this area. Rescue at this location is presumed to be unlikely (COSEWIC 2019)

Other ecosystem modifications

Many dune and beach habitats in Ontario that are adjacent to cottages and residential areas experience vegetation removal and stabilization of dunes by residents. This ecosystem modification is expected to have contributed to the extirpation of the species at Deans Bay and may limit the feasibility or effectiveness of reintroducing the species to that location. No residences or cottages currently exist on Great Duck Island, so this threat is not expected to affect the extant subpopulations of Gillman’s Goldenrod (COSEWIC 2019). However, due to the private landownership of Great Duck Island, this potential threat should not be dismissed.

Herbivory

White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) browsing and insect herbivory have not been noted to impact Gillman’s Goldenrod; however, the levels of herbivory may vary from year to year (COSEWIC 2019). Impacts from herbivores are expected to be a negligible threat to the species.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Species biology

No information is available on the age of plants at maturity, the trigger for flowering, lifespan, pollinator species, pollination success, seed set, seed viability and germination requirements of Gillman’s Goldenrod.

Habitat dynamics and species needs

In order to better protect and manage habitat, we need to know more about the factors that create or maintain habitat in a suitable state and fill knowledge gaps related to habitat requirements and dynamics. A better understanding of the species’ preferred microhabitat conditions, moisture regime and disturbance regime that optimizes plant condition may assist in habitat management and facilitate population augmentation if that becomes necessary in the future.

Population trends and subpopulation viability

Long-term population trends and the long-term effects of current threats are knowledge gaps that have never been quantified for the Ontario subpopulations of Gillman’s Goldenrod. Information on population viability is needed to know whether additional recovery actions, such as reintroductions or augmentation by seeding or transplantation, may be required. Genetic or genomic studies may be beneficial to evaluate recovery needs and suitable approaches to satisfy them.

Dormancy periods are not known for this species; however, apparent dormancy from sand burial may occur. Additional long-term monitoring may be warranted to confirm if Gillman’s Goldenrod has dormancy periods and study the adaptation to dune dynamics.

Presence and effect of additional non-native species

Presence and effect of additional non-native species on Great Duck Island that may pose a threat to either subpopulation should be assessed.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Inventory

Field surveys of Gillman’s Goldenrod and its habitat were completed at 20 potentially suitable sites in Manitoulin District in 2018 as part of the development of the COSEWIC status report (2018). This fieldwork supported that, in Ontario, Gillman’s Goldenrod is currently extant only on Great Duck Island (COSEWIC 2019).

Habitat management

Removal of European Reed from Deans Bay was completed in 2016. European Reed was removed from Horseshoe Bay by the Manitoulin Phragmites Project, which completed management from 2016 to 2018 (Jones 2019). As of 2019, European Reed was confirmed to be removed from all sand dune habitat on Great Duck Island; however, surveys in 2018 confirmed the presence of European Reed at Old Harbour on Great Duck Island, which still needs assessment and removal (Jones 2019). The fact that European Reed remains present on Great Duck Island increases the potential for its reestablishment in the dune habitats. No management of Glandular Baby’s-breath has occurred on Great Duck Island.

Outreach

Upon being assessed as Endangered by COSEWIC, Gillman’s Goldenrod made an appearance in a local news article in the Manitoulin Expositor (Thompson 2021). This article has since also been published online by Sudbury.com and the Toronto Star. The article provided information on the range, habitat and conservation status of Gillman’s Goldenrod. Photos of the Gillman’s Goldenrod were included, and a limited description of the species’ appearance was provided in text.

Dune conservation signage and dune displays not specific to Gillman’s Goldenrod are in place at multiple dune locations on Lake Huron, including Dominion Bay, Manitoulin Island and on the Chi-Cheemaun ferry (OMNR 2013).

Policy, legislation and planning

Great Duck Island is located in the unorganized part of Manitoulin District and is outside of the Manitoulin Planning Area; however, it is considered part of the Town of Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands. Therefore, the habitats containing extant Gillman’s Goldenrod may receive protections through municipal policies or municipal review process for proposed developments under the Planning Act. Habitats of extirpated occurrences of Gillman’s Goldenrod (i.e., Deans Bay) are within the Manitoulin Planning Area and are therefore subject to the shoreline and natural heritage protection policies of the District of Manitoulin Official Plan (2018).

Additionally, there are provincial policies and legislation that apply to suitable habitat of Gillman’s Goldenrod. The entirety of Great Duck Island is mapped as a Provincially Significant Life Science Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI) (see Figure 3). The Great Duck Island Life Science ANSI would be provided protection under the Provincial Policy Statement (2020) and Planning Act. In absence of a municipal review process, development applications may be required to go through a provincial Environmental Assessment through Ontario’s Environmental Assessment Act, 1990. The Environmental Assessment process would consider impacts to the ANSI, Species at Risk and provincially rare vegetation communities, including dunes.

Figure 3. Great Duck Island Provincially Significant Life Science Area of Natural or Scientific Interest (NHIC 2021a).

Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) provides science-based assessment, automatic species protection, and habitat protection, in order to protect Species at Risk in Ontario. Unauthorized destruction of Species at Risk and their habitats constitutes a contravention of the ESA.

Biological Control

Biological control agents for Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos) have been released in Minnesota (Minnesota Department of Agriculture 2021) and may naturally disperse to the Manitoulin Region over time. Seedhead weevils (Larinus minutus and L. obtusus) and root weevils (Cyphocleonus achates) have been released and are being provided to landowners in the United States for ongoing releases free of charge. Both species of seedhead weevil have been observed in southern Ontario.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recommended recovery goal

A vital aspect for recovery of Gillman’s Goldenrod is to complete studies that monitor population trends and assess the viability of each subpopulation. Until further information regarding population viability is available, the recommended recovery goal for Gillman’s Goldenrod is to maintain the current abundance and distribution of both extant subpopulations in Ontario. Once an effective population size for each subpopulation has been determined, the recommended recovery goal should be to increase or maintain subpopulation size and distribution to viable levels.

2.2 Recommended protection and recovery objectives

Recommended protection and recovery objectives include:

- assess threats and undertake actions to eliminate them or reduce the severity of their impact

- protect and maintain Gillman’s Goldenrod habitat using policy and legislative tools, where appropriate

- raise awareness about Gillman’s Goldenrod and its habitat

- fill knowledge gaps

The validity of the location data on the specimen from Deans Bay is debated (J. Jones pers. com. 2021) but if it did occur there previously the subpopulation would have been naturally marginal (J. Semple pers. com. 2021). Reintroduction to the historic location at Deans Bay should be considered a low priority at this time and may never be warranted due to the current land-use and uncertainty regarding the historic record. Current knowledge gaps on the species’ biology may reduce the success of reintroduction efforts and the anthropogenic impacts suspected of causing the loss of Gillman’s Goldenrod at Deans Bay are still present. Additionally, the naturally marginal population size would require greater effort to maintain and have less probability of success. Reintroduction at Deans Bay should only be considered with support from the local community and should involve public education programs to reduce anthropogenic threats prior to introduction. Reintroduction to Deans Bay should only be considered in the future if threats are expected to extirpate the species from Great Duck Island.

2.3 Recommended approaches to recovery

Table 2. Recommended approaches to recovery of the Gillman’s Goldenrod in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, management, inventory, monitoring and assessment, research, education and outreach, communication, stewardship | 1.1 Liaise with the private landowner and First Nations.

|

Threats:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, management, inventory, monitoring and assessment, research, education and outreach, communication, stewardship | 1.2 Complete or support recovery actions on Great Duck Island. Actions may include but are not limited to the following:

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Long-term | Protection, management, inventory, monitoring and assessment, research, education and outreach, communication, stewardship | 1.3 Support or implement the acquisition of Great Duck Island for conservation purposes.

|

Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Protection, education and outreach, communication | 2.1 Encourage the town of Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands to develop and enforce an Official Plan according to the requirements in the Provincial Policy Statement that includes the protection of rare habitats and habitat for SAR.

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Protection, education and outreach, communication | 2.2 Encourage the Manitoulin Planning Board to update their Official Plan and develop a Natural Heritage System in accordance with the requirements in the Provincial Policy Statement.

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Protection, education and outreach, communication | 2.3 Town of Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands to continue to recognize Great Duck Island ANSI and to develop policies for its protection.

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Protection | 2.4 Develop and enforce provincial legislation for the protection of sand dune habitat in Ontario.

|

Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, education and outreach, communication or stewardship | 3.1 Discuss Gillman’s Goldenrod and the importance of dune habitats with the private landowner of Great Duck Island.

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Protection, education and outreach, communication or stewardship | 3.2 With permission from the landowner, support or implement dune conservation outreach signage in key locations where boaters and kayakers frequent.

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Protection, education and outreach, communication or stewardship | 3.3 Discuss Gillman’s Goldenrod with First Nations communities and municipal planners in the Manitoulin Region.

|

Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory, monitoring and assessment, research | 4.1 Develop and implement a monitoring program to determine population trends, monitor threats and assess population viability.

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Inventory, monitoring and assessment, research | 4.2 Study Gillman’s Goldenrod’s and confirm if this species exhibits dormancy periods. | Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Management, inventory, monitoring and assessment, research, stewardship | 4.3 Research factors that create or maintain habitat suitability in order to improve habitat management.

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research, stewardship | 4.4 Study Gillman’s Goldenrod in order to increase general species knowledge including but not limited to pollinator species, seed dispersal, germination requirements, microhabitat, moisture regime, response to invasive species, response to dune dynamics and succession, genetics and subpopulation viability. | Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

Gillman’s Goldenrod has specific habitat requirements and a very restricted distribution in Ontario. The current distribution has likely not contracted from its historical extent, except for the extirpation of the subpopulation at Deans Bay over 18 years ago. The population at Deans Bay is expected to have been naturally marginal (J. Semple pers. com. 2021). The subpopulation record at Deans Bay is based on a single specimen collected in 1976 by botanists who had recently visited Great Duck Island (J. Jones pers. com. 2021). The specimen’s location may have been mislabeled; however, there is no way to prove or disprove the validity of this record (J. Jones pers. com. 2021). The specimen was not recognized as Gillman’s Goldenrod until 1985 (University of Waterloo Herbarium, Specimen# MT00228067) and no records of this species at Deans Bay exist from after 1976. Extirpation from Deans Bay was confirmed between 2000 and 2018 (COSEWIC 2019).

The Ontario distribution of Gillman’s Goldenrod is unlikely to expand without human-assisted introduction because, although potentially suitable habitat exists at other locations, the distance to other suitable habitats and inherent limitations in dispersal distance mean that natural dispersal is highly unlikely. Botanical experts in Ontario have asserted that reintroduction of Gillman’s Goldenrod to Deans Bay is a low priority and that introduction of the species to potentially suitable dune sites where it was not historically known should not be attempted (J. Jones pers. com 2021; S. Brinker pers. com. 2021; W. Bakowsky pers. com. 2021).

The main threat to extant subpopulations of Gillman’s Goldenrod is invasive non-native plant species. Removal of Common Reed has occurred at one subpopulation; however, Glandular Baby’s-breath remains a threat. In Michigan, effective removal of Common Baby’s-breath has been completed ‘leeward’ (meaning moving with the wind direction) to avoid leaving behind plants that will re-introduce seed to treated areas (Nature Conservancy 2015). The actual control methods have included both manual removal and chemical control with herbicide, such as glyphosate Roundup™ (Nature Conservancy 2015). Glandular Baby’s-breath has a long taproot that makes pulling by hand difficult and can result in the survival of broken roots and removal with assistance from a shovel or spade is recommended (Albert 2000; Nature Conservancy 2015). Hand-pulling and chemical control have also been used to control knapweeds in the United States (Nature Conservancy 2015). Invasive species removal from Great Duck Island is vital to achieving the interim recovery goal of maintaining the existing population levels because Glandular Baby’s-breath is expected to cause population declines at Horseshoe Bay. This recovery action should occur as soon as possible to prevent population reduction from occurring.

Additional problematic non-native species have not yet been noted as a current threat to Gillman’s Goldenrod in Ontario. However, the presence of potentially problematic non-native species on Great Duck Island should be monitored periodically so that recovery actions can include early detection and rapid response mitigation. Removal of non-native invasive species in Gillman’s Goldenrod habitat should be followed with monitoring to ensure a secondary invasion by other problematic species does not occur. Habitat restoration post-removal may be warranted; however, leaving areas of open sand for Gillman’s Goldenrod to colonize is also vital.

Ongoing anthropogenic threats mainly affect the extirpated location and other potentially suitable habitats. The remoteness of Great Duck Island may reduce the severity or potential of these threats at the extant subpopulations. Anthropogenic threats include, but are not limited to, construction or development, habitat alteration and recreational activities. Gillman’s Goldenrod currently occurs on lands where there is little presence of ownership or jurisdictional authority, with no roads, occupied residences, or signage. Recreational use of these habitats is unmonitored and may vary seasonally: e.g., more ideal summer weather conditions may increase boat traffic, especially kayaks which are more easily able to access beaches (kayak visits to Great Duck Island are described on the internet). Great Duck Island occurs outside of the Manitoulin Planning Area and is included within the Town of Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands. A formal municipal review process for proposed developments, construction activities or extraction is not in place within the Manitoulin Region to provide sand dune habitats the protection they are afforded under the Provincial Policy Statement. In absence of implementing a municipal review process any proposed development on the island may require a provincial environmental assessment process. Additional provincial policies and legislation that protects the entire sand dune complex would benefit Gillman’s Goldenrod and other Species at Risk in Ontario by providing more comprehensive and concrete protection to this dynamic ecosystem.

Great Duck Island is a single parcel of private land. Private ownership may restrict the ability to perform monitoring, research or recovery actions. The acquisition of Great Duck Island for conservation purposes may be a vital approach to provide property access and permission to perform recovery actions. Short-term approaches for recovery include liaison with the existing landowner to permit completion of recovery actions; however, if that is unsuccessful, land acquisition may be the only option to ensure protection and recovery.

The abundance of Gillman’s Goldenrod at both subpopulations on Great Duck Island is currently high; however, monitoring is required to fill knowledge gaps about subpopulation trends and viability. Development and implementation of a monitoring protocol will allow for trends to be observed between subpopulations and assist in ongoing threat assessment. If Gillman’s Goldenrod is not observed at currently extant locations (Desert Point and Horseshoe Bay) over a period of two to three consecutive years, or if long-term monitoring suggests a decreasing population size or that the current levels are not viable, reintroduction or augmentation actions should be considered.

As Great Duck Island is under land claim by Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, First Nations may have a key role in recovery of Gillman’s Goldenrod. It is recommended that First Nations be included in recovery processes where possible to promote partnership and outreach.

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks on the area that should be considered if a habitat regulation is developed. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister, including information that may become newly available following the completion of the recovery strategy should a habitat regulation be developed for this species.

Considerations

Occupancy

Gillman’s Goldenrod is a long-lived, rhizomatous, perennial plant. If Gillman’s Goldenrod is observed during the growing season, the entire contiguous dune system (as delineated by ELC) should be considered occupied. Dormancy periods (where the plant does not produce above ground growth) have not been observed in this species, but sand burial may cause a temporary disappearance of individuals. Gillman’s Goldenrod can only be conclusively identified when the plants are in flower or fruit. Occupancy should therefore be determined by a qualified individual when flowering or fruiting plants are present (i.e., late August to early October). Individuals may not flower every year and only sterile rosettes may be present. Confirming a lack of occupancy is much more challenging and would require extensive survey efforts. For the purposes of a regulated area, occupancy of the dunes at extant locations (i.e., Horseshoe Bay and Desert Point) should be assumed unless no plants are observed for a period of fifteen consecutive years. Fifteen years is the high end of the expected generation time, which is assumed to be 5 to 15 years (COSEWIC 2019; COSARO 2020). A lack of presence at one location should not be used to justify an assumption of lack of occupancy at the other.

Maintaining abundance levels at current extant locations is the primary recovery goal for Gillman’s Goldenrod. Protection of dune habitat at these locations should continue even if occupancy is not observed. If occupancy is not observed for over five consecutive years (the minimum assumed generation range) reintroduction or augmentation actions should be undertaken as a high priority to recover the subpopulation. Augmentation actions may be considered earlier if declines are observed during monitoring.

Dynamics and maintenance of suitable habitat

Gillman’s Goldenrod has only been noted within one ELC vegetation type (Little Bluestem – Long-leaved Reed Grass – Great Lakes Wheatgrass Open Dune [SDO1-2]). The dune community extends inland to where trees represent 60% or more cover (OMNR 2013). The area of occupancy may not cover the entire ELC polygon, but due to natural fluctuations, it is recommended that the entire ELC polygon is required to provide habitat over time as dunes and zonation within the beach-dune complex shift. Dunes are dynamic ecosystems, and their boundaries fluctuate naturally over time. It is important to consider potential fluctuations when developing habitat regulation for Gillman’s Goldenrod.

Disturbances to areas adjacent to the dune (e.g., the shoreline and/or beach below or stabilized areas above) may affect dune dynamics that are necessary to maintain habitat suitability for Gillman’s Goldenrod. Beaches occurring between the water’s edge (as defined as the low-water mark) and the base of the dune (as defined by ELC) should be included in the area considered in developing a habitat regulation. Beaches play a critical role in dune dynamics and development, or site alteration of beaches may alter processes that maintain dune openness and instability (e.g., sand deposition, frost heave, wave action, ice scour and wind) (Packham and Willis 1997; Martinez and Psuty 2004; Callaghan 2008). Dunes and the beaches that occur adjacent are part of a linked system and to maintain the physical and ecological characteristics of dune habitats the complete beach-dune system must be preserved.

The area recommended for consideration in developing a habitat regulation below aims to protect extant individual plants as well as protecting the habitat necessary to allow for the establishment of new individuals in an ecosystem where specific areas of suitable habitat for germination and growth may shift with dune dynamics. Since this species is restricted to only two dunes in Ontario, protecting the entire beach-dune system is necessary to achieve the goal of maintaining the current population level or increasing them to viable levels once those levels have been determined.

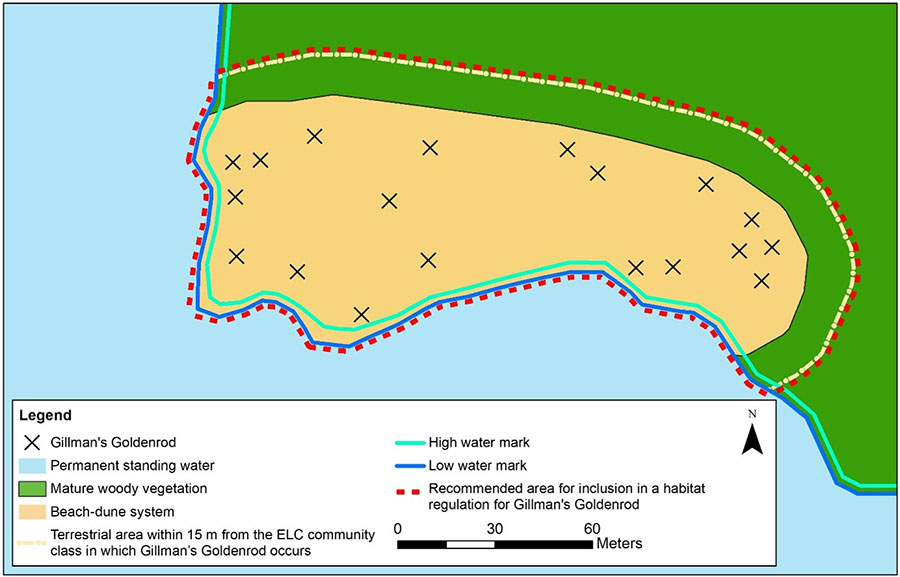

The area recommended to be considered for inclusion in a habitat regulation for Gillman’s Goldenrod includes:

- all areas where Gillman’s Goldenrod is present and any new areas that are discovered

- the entire Ecological Land Classification (ELC) Community Class in which Gillman’s Goldenrod is present

- the complete beach-dune system in which Gillman’s Goldenrod is present from the low water mark of the lake shore to the belt of mature vegetation behind the dunes in order to protect the dynamics of the dunes and allow for constant natural changes

- all of the terrestrial area within a distance of 15 m from the ELC Community Class in which Gillman’s Goldenrod occurs, including unsuitable habitat

The terrestrial areas within 15 m of the occupied ELC Community Class boundary will overlap with the belt of mature vegetation behind the dunes. All terrestrial areas within 15 m of the ELC Community Class in which Gillman’s Goldenrod occurs has been included in the area recommended to be considered for inclusion in a habitat regulation so that if individuals occur at the edge of a Community Class polygon there will be sufficient distance from activities in adjacent areas to prevent risk of impacts. Furthermore, this recommendation protects the ecological function of the beach-dune system by providing a minimum buffer from potential impacts and provides space for dune dynamic processes to occur. The habitat regulation for Pitcher’s Thistle, which also occurs in dune habitats, includes sand dunes with less than 25% tree cover (ELC Community Series of Open or Shrub Sand Dune) where Pitcher’s Thistle exists and areas of natural vegetation within 15 m from the edge of the sand dune (Government of Ontario 2021). Due to the very restricted range of Gillman’s Goldenrod, it is vital that the dune dynamics that provide suitable habitat for this species are maintained at the locations of these subpopulations. As such, the recommendation provided here included the entire dune system including the entire area of Community Class (e.g., Sand Dune including Open, Shrub and Treed Sand Dune Community Series), the beach below the dune down to the low water and the area above the Sand Dune Community Series that are within 15 m, including areas unsuitable for Gillman’s Goldenrod. A conceptual illustration of the area recommended to be considered for inclusion in a habitat regulation for Gillman’s Goldenrod is provided in Figure 4. Note that this figure does not represent a real location and is not to scale.

Figure 4. The area recommended to be considered for inclusion in a habitat regulation for Gillman’s Goldenrod.

There is no existing infrastructure present in the habitat of extant subpopulations of Gillman’s Goldenrod on Great Duck Island. If future reintroductions are undertaken at Deans Bay or if additional occurrences are located elsewhere where infrastructure is present, it is recommended that existing infrastructure within the habitat not be prescribed as habitat.

Glossary

- Achene

- A small, dry one-seeded fruit that does not open to release the seed that are formed from one carpel.

- Acute

- Describing a leaf apex that forms an angle of less than ninety degrees appearing as a sharply pointed tip. This includes leaf tips with angles between 45-89°.

- Barrier dune

- The first landward sand dune formation along a shoreline. Barrier dunes may form a barrier island and consist of multiple elongate sand ridges rising above water level and extending parallel with the coast and separated from the coast with a lagoon.

- Basal

- Forming or belonging to a bottom layer or base.

- Bayhead beach dune

- A dune classification including cove dunes (dunes formed on intermittent ribbons that fill irregular rocky coastlines) and big bay dunes (dunes formed at the heads of large, shallow, arcuate bays that are typically large systems with a transverse foredune and subsequent secondary dune ridges)

- Bisexual plant

- Each flower of each individual has both male and female structures. Other terms used for this condition are androgynous, hermaphroditic, monoclinous and synoecious.

- Blowout

- Streamlined spoon shape dune formation caused by sufficiently large disruption such as washover or human activities.

- Calcareous

- Mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate or containing lime. Often calcareous soils are influenced by underlying chalk or limestone but calcareous sands may be comprised of crushed up shells or bones. Typically have a pH of 8.0 to 8.2.

- Calyx

- The sepals of a flower, typically forming a whorl that encloses the petals and forms a protective layer around a flower in bud.

- Cauline

- Growing on a stem and especially arising on the upper part of the stem.

- Cliff dune

- Dunes formed by strong winds eroding the loose sand from the face of bluffs, forming high, wide dunes.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC)

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO)

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank

- A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. Infraspecific These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Taxon (trinomial) (T) is the status of infraspecific taxa (subspecies or varieties) and is indicated by a "T-rank" following the species’ global rank. Ranks are determined by NatureServe and, in the case of Ontario’s S-rank, by Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

- 1 = critically imperiled

- 2 = imperiled

- 3 = vulnerable

- 4 = apparently secure

- 5 = secure

- NR = not yet ranked

- ? = inexact numeric rank indicating some uncertainty

- Convection current

- A process that involves the movement of energy from one place to another.

- Crenate

- Describing a leaf margin that appears scalloped or with rounded teeth.

- Cypselae

- a dry single-seeded fruit that does not split open during seed dispersal and that is formed from a double inferior ovary of which only one develops into a seed. Cypselae are characteristic of the plant family Asteraceae.

- Dentate

- Describing the margin of a leaf with sharply pointed teeth directed outward rather than forwards.

- Disk floret

- Small tubular and typically fertile floret that form the disk in a composite plant.

- Dune

- A mound, hill or ridge of sand or other loose sediment formed by wind or water.

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA)

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Floret

- One of the small flowers making up a composite flower head.

- Germinability

- The capacity to germinate (to cause to sprout or develop)

- Gynecandrous

- Having staminate and pistillate flowers in the same spike or spikelet, with pistillate flowers grouped above staminate.

- Inflorescence

- The flowering part of a plant including stem, stalks, bracts and flowers.

- Involucre

- A whorl or rosette of bracts surrounding a flower head.

- Obovate

- Describing a roughly egg-shaped leaf with the narrower end at the base.

- Paniculiform

- Describes the arrangement of an inflorescence that resembles a panicle (a loosely branched inflorescence with clusters of flowers).

- Pappus

- A modified calyx made up of a ring of fine hairs, scales, or teeth that persist after fertilization and aid the wind dispersal of the fruit, often by forming a parachute-like structure. An example is the white tufts that disperse dandelion seeds.

- Parabolic dune

- Secondary dune features evolving from deflated transverse dunes that form with the stabilizing effect of vegetation.

- Perennial plant

- A species of plant with individuals that persist for several years. Perennials grow back from root systems that may go dormant seasonally.

- Phyllaries

- Bracts of the involucre of a composite flower. Reduced leaf-like structures that form one or more whorls immediately below a flower head.

- Pistillate

- A female flower or individual plant with flowers that exclusively contains the reproductive anatomy required in the production of female reproductive cells.

- Ray Floret

- Strap-shaped flowers typically occupying the peripheral rings of composite plants.

- Resinous

- To be full of or contain resin (a thick sticky substance produced by some trees).

- Rhizome

- A elongated subterranean plant stem which typically grows horizontally, producing lateral shoots and adventitious roots at intervals. Distinguished from true roots by possessing buds, nodes, and typically scalelike leaves.

- Rhizomatous

- Plant having a horizontal underground stem whose buds develop new roots and shoots.

- Rosette

- A circular arrangement of leaves or of structures resembling leaves.

- Serrate

- Describing the margin of a leaf with sharply pointed teeth with teeth pointing forwards.

- Sheathing

- Protective casing or covering.

- Spatulate

- Describing a leaf shape with broad rounded ends.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA)

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This Act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Strigose

- Covered with short stiff adpressed hairs.

- Succession

- changes in vegetation communities over time; plant communities often but not always, succeed to being more woody perennial (tree and shrub) dominated.

- Tetraploid

- An organism with four sets of homologous chromosomes (i.e., 4n).

- Transverse dune

- Large, strongly asymmetrical, elongated dune lying at right angles to the prevailing wind direction. These formations have a seep slope on the leeward side and a gentle slope on the windward side.

List of abbreviations

- COSEWIC

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

- COSSARO

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario

- CWS

- Canadian Wildlife Service

- EIS

- Environmental Impact Study

- ELC

- Ecological Land Classification

- ESA

- Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007

- ISBN

- International Standard Book Number

- MECP

- Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

- MNDMNRF

- Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry

- SARA

- Canada’s Species at Risk Act

- SARO List

- Species at Risk in Ontario List

- WUT

- Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory

References

Albert, D. 2000. Borne of the Wind: An introduction to the ecology of Michigan's sand dunes. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, Mi. 63 pp.

Bakowsky, W.D. and B.L. Henson. 2014. Rare Communities of Ontario: Freshwater Coastal Dunes. Natural Heritage Information Centre. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 10 pp. + appendices.

Buchele, D., J. Baskin and C. Baskin. 1992. Ecology of the Endangered Species Solidago shortii. IV. Pollination Ecology. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(2):137-141.

Callaghan, T. 2008. Improving the health of Lake Huron coastal dunes by development of a stewardship guide. A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph, In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture, 107 pp.

Carthey, A.J.R., K.A. Fryirs, T.J. Ralph, H. Bu and M.R. Leishman. 2016. How seed traits predict floating times: a biophysical process model for hydrochorous seed transport behaviour in fluvial systems. Freshwater Biology 61:19-31

Chapman, L.J. and D.F. Putnam. 1984. The physiography of southern Ontario, 3rd Edition. Ontario Geological Survey, Special Volume 2, 270 pp. Accompanied by Map P.2715 (coloured), scale 1:600 000.

COSARO. 2020. Ontario Species at Risk Evaluation Report for Gillman’s Goldenrod (Solidago gillmanii). Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSARO), 12 pp.

COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on Pitcher's thistle Cirsium pitcheri in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 14 pp.

COSEWIC 2005. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Houghton's goldenrod Solidago houghtonii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 17 pp.

COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Showy Goldenrod Solidago speciosa (Great Lakes Plains and Boreal Populations) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiv + 23

COSEWIC. 2019. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Gillman’s Goldenrod Solidago gillmanii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 43 pp.

Cowles, H. C. 1899. The ecological relations of the vegetation on the sand dunes of Lake Michigan. Botanical Gazette 27: 95-391.

Czarnecka, J., G. Orłowski and J. Karg. 2012. Endozoochorous dispersal of alien and native plants by two palearctic avian frugivores with special emphasis on invasive giant goldenrod Solidago gigantea. Open Life Sciences 7(5):895-901.

Davidson-Arnott, R. 2016. Climate Change Impacts on the Great Lakes: A discussion paper on the potential implications for coastal processes affecting the SE shoreline of Lake Huron within the jurisdiction of the Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority. Draft prepared for the Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority. 15 pp.

Davidson, R.J. 1990. Protecting and managing great lakes coastal dunes in Ontario. Proceedings Canadian Symposium of Coastal Sand Dunes 1990, 455-471.

District of Manitoulin. 2018. District of Manitoulin Official Plan. Approved by MMAH on October 29, 2018. 260 pp. Available Online.

Emery, S., P. Doran, J. Legge, M. Klietch and S. Howard. 2013. Aboveground and Belowground Impacts Following Removal of the Invasive Species Baby’s-breath (Gypsophila paniculata) on Lake Michigan Sand Dunes.

Government of Ontario. 2021. O. Reg. 242/08: GENERAL: Under Endangered Species Act, 2007, S.O. 2007, c. 6. Accessed January 14th, 2022.

Gross, R.S. and P.A. Werner. 1983. Relationships among flowering phenology, insect visitors, and seed-set of individuals: experimental studies on four co-occurring species of goldenrod (Solidago: Compositae). Ecological Monographs 53(1):95-117.

Jones, J.A. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Houghton’s Goldenrod (Solidago houghtonii) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 31 pp.

Jones, J. 2019. The Manitoulin Phragmites Project Results of 2019 Work. Letter report compiled by the project coordinator. 7 pp.

Kartesz, J.T., The Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2015. Taxonomic Data Center. Chapel Hill, N.C. [maps generated from Kartesz, J.T. 2015. Floristic Synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP). (in press)]

Lee, H. & Bakowsky, Wasyl & Riley, J. & Bowles, J. & Puddister, M. & Uhlig, P. & Mcmurray, S.. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application.

Martini, I.P. 1981. Coastal dunes of Ontario: Distribution and geomorphology. Geographie physique et Quaternaire 25(2):219-229.

Martinez, M. L. and N. P. Psuty. 2004. Coastal Dunes: Ecology and conservation. Ecological studies v. 17. New York: Springer

Michigan Flora Online. A. A. Reznicek, E. G. Voss, & B. S. Walters. 2011. University of Michigan. Web. August 3, 2021.

MNRF (Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry). 2021. Crown Land Use Policy Atlas.

Minnesota Department of Agriculture. 2021. Spotted Knapweed Control.

Morton, J.K. and J.M. Venn. 2000. The Flora of Manitoulin Island, 3rd ed. University of Waterloo Biology Series Number 40. Waterloo, Ontario.

Nature Conservancy. 2015. Lake Michigan Coastal Dunes Restoration Project: 2015 Field Season Report. Report prepared by the Nature Conservancy and partners. 15 pp.

Nature Serve Explorer. 2021. Solidago simplex var. gillmanii Dune Goldenrod.

NHIC (Natural Heritage Information Centre). 2021a. Make a Map: Natural Heritage Areas. Accessed August 11th, 2021.

NHIC (Natural Heritage Information Centre). 2021b. Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre. Occurrence data for Gillman’s Goldenrod in Ontario provided to the authors.

OMNR (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources). 2013. Recovery Strategy for the Pitcher’s Thistle (Cirsium pitcheri) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. iii + 5 pp + Appendix x + 31 pp. Adoption of the Recovery Strategy for the Pitcher’s Thistle (Cirsium pitcheri) in Canada (Parks Canada Agency 2011).

Packham, J.R., and A. J. Willis. 1997. Ecology of dunes, salt marsh, and shingle. 1st ed. New York: Chapman & Hall.

Peach, G. 2006. Management of Lake Huron’s Beach and Dune Ecosystems: Building up from the Grassroots. The Great Lakes Geographer 13(1):39-49.