Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy

Read the strategy to protect and restore the Lake Simcoe watershed as we adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Disclaimer: The Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy is not and should not be construed as legal advice. The purpose of this document is to provide guidance in the implementation of the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan. Any legislation or regulations referred to in this strategy can be reviewed on the e-laws website or on the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change website. If there is any conflict between the Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and the Lake Simcoe Protection Act, any regulation made thereunder, or the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan, the legislation, regulation, or Plan prevails over the strategy. Should you have any questions about the application or interpretation of the laws of Ontario or have other legal questions, you should consult a lawyer.

Overview

Ontario is taking a leadership role in the fight against climate change. Ontario’s Climate Change Action Plan establishes forward thinking policies and programs — cap and trade, a vast transit network, energy conservation and efficiency initiatives, vehicle emission reductions and green infrastructure projects — to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and move the province toward a low carbon future.

A comprehensive approach to fighting climate change also requires actions to reduce our vulnerabilities and adapt to the impacts of climate change such as extreme weather events. Having experienced rapid human growth during the 20th century, and seeing the resulting impacts on the ecological health of Ontario’s watersheds, adapting to climate change is a serious environmental concern that is a provincial priority. Ontario is developing an adaptation plan to be released in 2017 that will outline how the province will be better prepared for the impacts of climate change. This plan is supported by extensive work being undertaken in the Lake Simcoe watershed to adapt.

The Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy takes a multi-faceted approach to drive actions in the Lake Simcoe watershed to adapt to our changing climate. Actions to address climate change and its impacts are being implemented throughout the watershed in collaboration with a range of stakeholders. A selection of ongoing work is highlighted in the strategy:

- Remote sensing of phosphorus across terrestrial landscapes builds knowledge of non-point source nutrient movements that enables more accurate models of water quality and better estimates of how nutrient loadings to the Lake will change under different climate change scenarios;

- Predictive modeling of forest carbon monitors vegetation to spatially track changes in the watershed and determine proportions of high quality natural vegetative cover to implement timely watershed management actions;

- Agricultural water use assessments in the Holland Marsh are helping farm operations assess their water use to implement water conservation actions to prepare for potential climate change impacts such as an increase in flooding and/or drought events;

- Modeling environmental flows in tributaries in the Lake Simcoe watershed helps land use authorities maintain stream flows required for healthy aquatic ecosystems that are adaptable to future climate change scenarios and development stresses in each subwatershed;

- Evaluating and understanding the value of the aquatic life within the Lake Simcoe watershed helps identify actions to adapt to changing climatic and lake conditions and the impacts on recreational fisheries and the associated socio-economic benefits.

Together, the Province and stakeholders are committed to taking practical short and long-term actions to adapt to climate change to protect and restore the Lake Simcoe watershed for future generations.

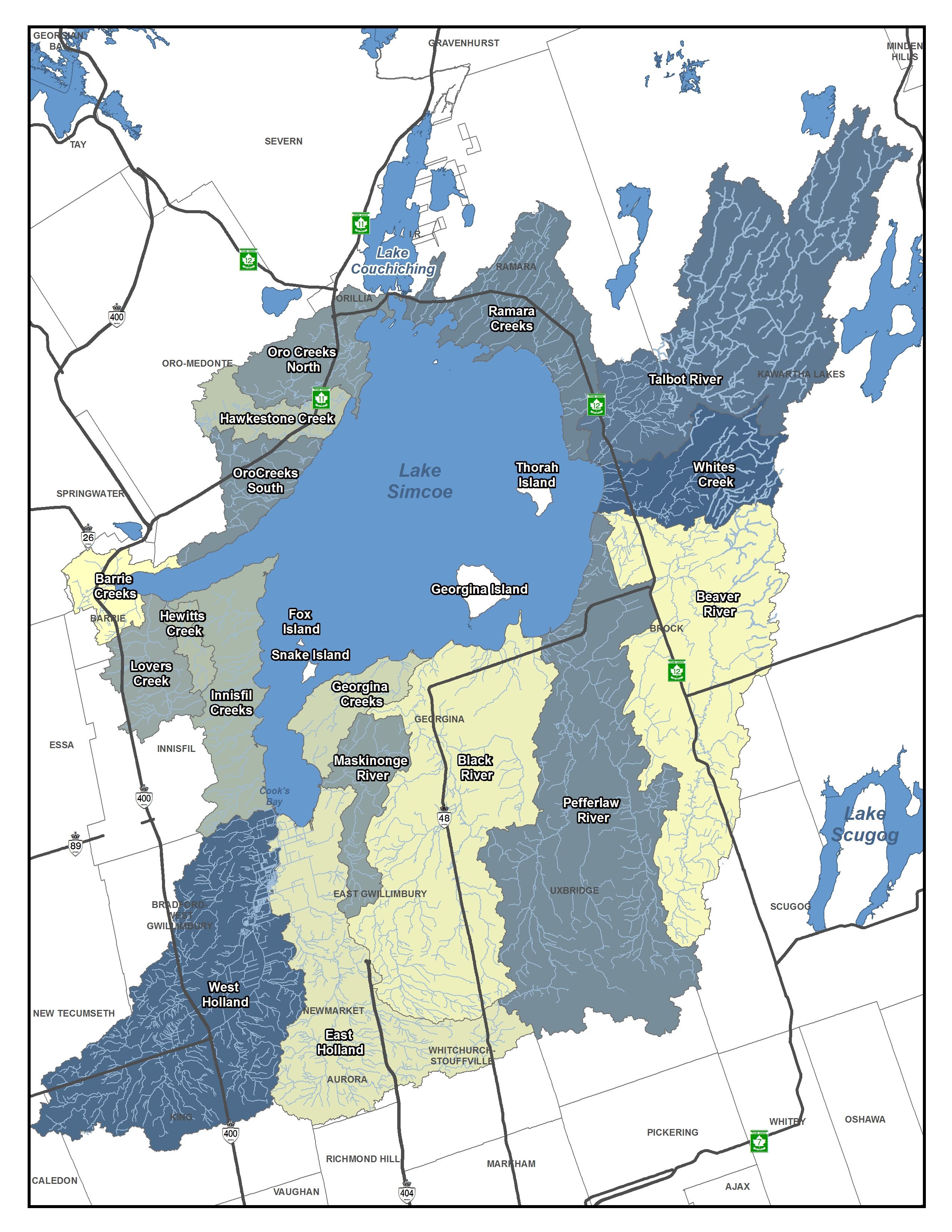

The Lake Simcoe watershed

Figure 1

Named Ouentironk (“beautiful water”) in the 17th century by the Huron who lived along its shores, Lake Simcoe has long been valued as an essential natural resource. Aside from the Great Lakes, it is the largest lake in southern Ontario, measuring 722 square kilometres, with a watershed measuring 2,899 square kilometres.

The Lake Simcoe watershed is home to diverse natural ecological features, including parts of the Oak Ridges Moraine and the Greenbelt, provides habitat for over 75 species of fish, provides hundreds of millions of dollars in agricultural revenue, and supports a robust tourism industry. Its watershed supplies drinking water to the local population and contains the traditional lands of many First Nations.

The health and well-being of people who live in the watershed is dependent on the ecological state of the lake. Regrettably, human activities have gradually altered the natural landscape of the Lake Simcoe area. The effects of excessive nutrients, pollutants, invasive species, development and recreational activities have degraded the water quality of the lake and its tributaries.

The Lake Simcoe Protection Act, 2008 and the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan (Plan), released in June 2009, committed the Province to addressing long-standing environmental issues in the Lake Simcoe watershed. The Plan takes a comprehensive approach to protect and restore the ecological health of the Lake Simcoe watershed, and to understand and mitigate the impacts of major ecological stressors, including climate change.

Climate Change impacts on the Lake Simcoe Watershed

The changing climate will affect Lake Simcoe’s water quality and quantity, aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem structure and function, the frequency of extreme weather events and could cause damage to natural areas and shorelines. These changes will influence the way communities throughout the Lake Simcoe watershed manage natural assets and the infrastructure that has been built around them. It is, therefore, important to adapt and respond to the ecological threats and opportunities ahead of us.

One of the objectives of the Plan is to “improve the Lake Simcoe watershed’s capacity to adapt to climate change.” The Plan also includes a climate change policy (Policy 7.11-SA), committing the Province to collaborating with its partners to develop a climate change adaptation strategy for the Lake Simcoe watershed.

The purpose of this strategy is to facilitate climate change adaptation within the Lake Simcoe watershed to ensure that the long-term health of Lake Simcoe is restored and protected now and in the future.

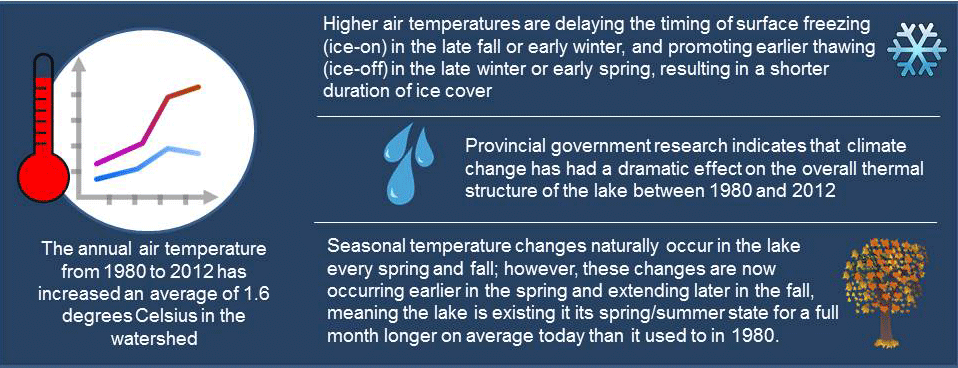

Figure 2

One of the objectives of the Plan is to “improve the Lake Simcoe watershed’s capacity to adapt to climate change.” The Plan also includes a climate change policy (Policy 7.11-SA), committing the Province to collaborating with its partners to develop a climate change adaptation strategy for the Lake Simcoe watershed.

The purpose of this strategy is to facilitate climate change adaptation within the Lake Simcoe watershed to ensure that the long-term health of Lake Simcoe is restored and protected now and in the future.

Lake Simcoe Climate Change adaptation strategy

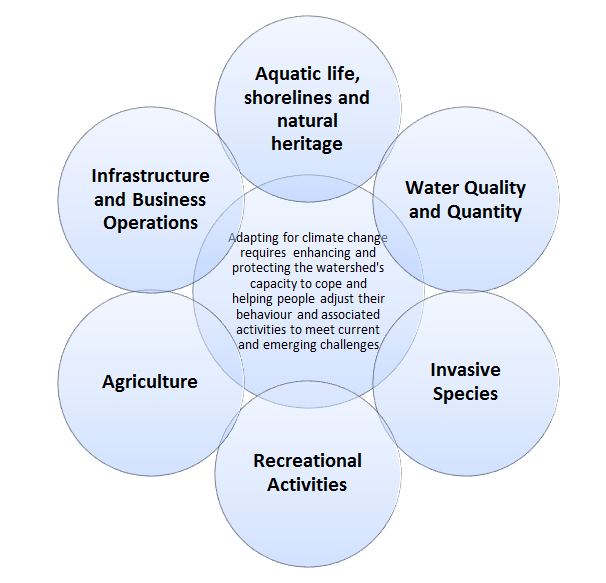

Figure 3

This strategy is a collaborative effort and a shared vision to integrate climate change into the management of the Lake Simcoe watershed. The strategy provides a framework to help all partners, including local governments (e.g., municipalities and First Nation/Métis communities), community partner agencies, the development community (e.g., planning authorities, developers, etc.), businesses, citizens, and interested stakeholders identify and implement adaptation measures to address the impacts of climate change in the watershed, in collaboration with the Province.

It builds on existing tools and mechanisms provided by other provincial strategies, policies, plans and legislation, including:

- Ontario’s Climate Change Action Plan;

- Ontario’s Climate Change Strategy;

- Climate Ready;

- Water Opportunities Act;

- Green Energy Act;

- Clean Water Act;

- Ontario Water Resources Act;

- Ontario’s Invasive Species Strategic Plan; and

- Planning Act.

Guided by principles of adaptive management, the following goals were set out for the development of the Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy:

- Identify ecological, socio-economic and infrastructure vulnerabilities to climate change as a basis for developing and prioritizing adaptation strategies;

- Develop a ‘climate ready’ strategic plan that complements existing commitments to help decision-makers design a way forward; and

- Use the experience and knowledge gained from this initiative to inform future adaptation projects in other parts of Ontario.

Vulnerabilities and strategic actions

Based on current scientific literature and analyses, climate change will continue to have a significant effect on the Lake Simcoe watershed. Specific impacts that climate change may have on the watershed are summarized below:

- Aquatic life, particularly coldwater fish species, are at risk because of increasing water temperatures in the lake, adjoining streams and rivers. Temperature increases will result in changes in fish recruitment, geographical distributions, and in biodiversity;

- Shorelines and wetlands will experience damage from increased drought and more intense rainfall as a result of climate change;

- Natural heritage areas may undergo biodiversity loss as many species will be unable to adjust to changing climate conditions and/or drought conditions. These natural heritage areas could be exposed to an influx of new, tolerant species, including invasive species;

- Number of bird species will increase in response to changes in summer and winter temperatures and precipitation. Spring breeding amphibians may call earlier, consequently lengthening their breeding period. Number of mammal species will increase by up to 20 per cent by 2100;

- Shifts in animal distributions and changes in their reproductive timing. Landscape fragmentation will influence the ability of animals to shift their distribution in response to climate change;

- Water quality will be degraded where there is an increase in phosphorus, contaminants, and sediments resulting from larger precipitation events or heavy melts in the early spring;

- Water quantity will suffer from a reduction in groundwater recharge;

- Winter recreation activities will be affected by decreases in ice thickness and duration of ice cover, specifically where water quality is degraded, where there is a shift in species distribution, and where ice fishing opportunities are limited due to changes in ice cover;

- Agriculture could suffer from drought, flooding crop damage, changes in yields, livestock animal stress, and increased costs of production; and,

- Infrastructure could be degraded from increased high-intensity storms, which can affect roads and sewer systems and/or treatment plants and increase nutrient and sediment loadings to the lake.

Similar to the Plan, this strategy identifies actions that should be taken to address specific areas that will likely be impacted by climate change. Actions have also been prepared for agriculture and infrastructure.

All partners should build these actions into their work plans over time and as opportunities arise. The ministry also looks forward to building on the continued success of engaging citizens and stakeholders, who have great interest in improving the health of Lake Simcoe through participation in a variety of stewardship projects.

1. Aquatic life, shorelines and natural heritage

Vulnerabilities

Climate change will significantly affect Lake Simcoe’s shorelines, aquatic habitats, natural heritage areas, health of the coldwater fishery and alter the warmwater fish community. These areas include the lake, its tributaries, adjacent wetlands, significant woodlands, and habitats for species at risk.

Potential changes may include:

- Reduced coldwater fish species habitat in the lake driven by increased phosphorus loading and depleted dissolved oxygen by end of summer. Range of warmwater fish species will expand, which may decrease diversity of prey fish species;

- Changes in stock recruitment rates. Warmer summers have positive effects on recruitment of smallmouth bass and northern pike; warmer falls/winters have negative effects on lake trout recruitment;

- Reduced ice cover over shallow waters where fish spawn, exposing their eggs to destructive wind and wave action;

- Higher levels of toxic contaminants in fish;

- Changing water cycle dynamics combined with increasing air temperature that may lead to the degradation or loss of wetlands;

- Shift or loss of biodiversity within woodlands, riparian zones and wetlands with new and invasive species entering the watershed;

- Changes to forest cover and ecosystem function due to increasing temperatures combined with changing precipitation patterns which could increase the frequency and scale of insect outbreaks, such as deer ticks;

- Increased production of pollens and spores;

- Changes in the abundance, condition and range of native plant and animal species;

- More extreme weather, including more frequent drought and more intense rainfall/flooding that may affect the shoreline integrity of the lake and its tributaries, adjacent wetlands, significant woodlands, and habitats for Species at Risk;

- Shifts in the hydrologic cycle that could impact water availability and water management, including groundwater quality/quantity and headwater tributary flows; and

- More sedimentation, point source and non-point source pollution from an increase in the frequency of extreme precipitation events.

Strategic actions

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should increase protection of aquatic and terrestrial natural heritage areas (such as wetlands, watercourses, and forests), as well as connections to urban green spaces (such as parks, backyards, boulevards, hedgerows and woodlots) in order to:

- Reduce climate change impacts on ecosystems and species;

- Protect and restore habitat for species at risk; and

- Facilitate the natural adaptive response of species to climate change.

1.1. Develop explicit terrestrial, aquatic, and rehabilitation targets to restore and maintain ecological integrity and ecosystem function in the watershed (e.g., set threshold targets for minimum forest cover and minimum stream base flows).

1.2. Support, promote and implement restoration programs in both built and natural areas by planting a diverse mix of indigenous tree species, including those expected to be better adapted to climate change, and maintain high levels of genetic diversity to reduce vulnerability to climate change impacts.

1.3. Maintain and improve functional stream corridors by reducing impacts from on-line ponds, barriers to fish movement where appropriate, and other factors that can alter the stream thermal regime.

2. Water quantity and quality

Vulnerabilities

A clean and sustainable water supply is critical to ecosystem function and human health and well-being. Climate-induced changes to water levels and flows could affect water quality and the ecological functions of natural areas and shorelines. Specifically, potential climate change impacts on Lake Simcoe water quality and quantity may include the following:

- Periodic failure or underperformance of sewage infrastructure;

- Periodic failure of flood-control infrastructure;

- Increase in loading of phosphorus and other nutrients to the lake;

- Increase in river and stream water temperatures;

- Increase in concentration of contaminants;

- Changes to the timing and delivery of nutrients, sediments and contaminants;

- Drinking-water supply concerns (for example, odour and taste problems due to increased weed and algae concentrations);

- Demand for water may exceed supply in some areas;

- Changes in ice cover may affect evaporation, infiltration, shoreline erosion, precipitation, seasonality and lake-effect snow;

- Reduction in groundwater recharge;

- Variation in stream-flow regimes and lake levels that affect fish and wildlife habitats, sediment deposition/transportation, erosion rates, and access to shorelines and natural heritage areas; and

- Increased periods of drought during hot summer months.

Strategic actions - water quantity

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should consider water conservation practices throughout the watershed.

2.1. Develop and implement water sustainability plans for municipal water services, including water conservation plans, an assessment of risks to future delivery of municipal services and plans to deal with those risks, as recommended for specific municipalities in Plan Policy 5.3.

2.2. Use adaptive management practices to ensure that water levels can be maintained and managed sustainably in response to changing climatic conditions.

2.3. Reduce dependence on traditional groundwater and surface water resources through use of alternative water sources, such as rainwater and greywater, and low impact development techniques and green infrastructure.

Strategic actions – water quality

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should adopt practices in the watershed to minimize the flow of nutrients and other pollutants into tributaries, groundwater and/or the lake at all times.

2.4. Implement Best Management Practices (BMPs) on land use to manage urban, rural and agricultural runoff and nutrient loading.

2.5. Develop joint programs through public/private partnerships that may include cost-sharing for innovative initiatives, such as rainwater harvesting, green roofs and greywater reuse.

2.6. Integrate climate change adaptation considerations and BMPs into manuals and guidelines available to people working in agriculture, land use development and other sectors.

3. Invasive species

Vulnerabilities

The spread of invasive species to and within Ontario is on the rise and, in some cases, may be facilitated by climate change. Invasive species disrupt food webs, degrade and eliminate habitat, introduce new parasites and diseases, and place indigenous species at risk of disappearing from localized areas or major parts of their range. Globally, only habitat loss is a greater threat to biodiversity than invasive species. There are potential significant ecological and economic consequences, including lost revenue from tourism and recreation, increased costs of managing invasive species, and damage to infrastructure. Once established, invasive species are difficult and costly to eradicate. Early detection and rapid response are critical to prevent invasive species from successfully establishing in the watershed’s ecosystems.

Climate change increases the risk of invasive species successfully establishing in the Lake Simcoe watershed as result of the following:

Increasing temperatures may create conditions in which established invasive species can increase their distribution and abundance. Warmer weather may lead to stress to fish species, allowing them to become increasingly vulnerable to impact of pathogens.

- Warming conditions may allow new invasive species to survive in regions where they may not have been able to establish previously in a cooler climate;

- Changing wind, air temperature and precipitation patterns may enhance seed dispersal of invasive plant species; and

- Pathogens and viruses, particularly those that are transported with or carried by other invasive species, could experience greater prominence in a warmer environment

Strategic actions

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should develop and implement early detection techniques and response strategies, as well as public education efforts, to limit the occurrence of invasive species in the Lake Simcoe watershed, building on the policies outlined in Chapter 7 of the Plan.

3.1. Research cumulative impacts and interacting stressors related to invasive species in the watershed.

3.2. Develop prevention, early detection and management approaches for aquatic and terrestrial invasive species.

3.3. Develop risk-based response plans for harmful invasive species.

4. Recreational activities

Vulnerabilities

Nature-based recreation opportunities including swimming, fishing and camping in the Lake Simcoe watershed attract thousands of residents and visitors. Recreational use is strongly correlated to climate. Climate influences water quality, snow cover and wildlife that combine to provide the outdoor recreational experience and influence the level of personal satisfaction (Jones and Scott, 2006). Given that the Lake Simcoe watershed provides significant opportunity for nature-based recreation, changes in climate and corresponding changes in ecosystem composition, structure and function will require adaptive shifts in human activities.

Lake Simcoe is the most intensively fished inland lake wholly within the boundaries of Ontario. It is both ecologically and economically distinct from many other lakes in the province. It is widely known as the “ice fishing capital of Canada”, and for its lake trout, lake whitefish, yellow perch and smallmouth bass fisheries. It draws an estimated one million angler hours per year and is the most southern inland natural lake trout lake in Canada.

Climate change could affect nature-based recreation and angling in many ways, including:

- Changes to ecosystem composition, structure, and function could affect visitor attractions, visitation patterns, the provision of recreational activities (e.g., ice fishing and snowmobiling), and the overall quality of the recreational experience;

- Changes in visitor behavioural responses, such as new or shifting destination and recreational preferences; (for example, how communities around the watershed adjust if there are reduced ice fishing opportunities).

- Increasing visitor safety concerns due to changes on the Lake Simcoe watershed (e.g., climate change-induced changes to water quality, thickness, quality, extent and duration of ice-cover on Lake Simcoe, air quality, beach closures).

Strategic actions

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should adopt an adaptive approach to sustain and enhance tourism and recreational activities that responds to the needs of both recreational users and businesses while maintaining the natural assets of the watershed in a changing climate.

4.1. Diversify attractions and destinations to offset demand for and/or losses to tourism and recreational activities, such as boating, snowmobiling and fishing, which may be affected by climate change.

4.2. Ensure the sustainability of fishing effort on coldwater species, recognizing that climate change may cause additional stress on these populations. Promote the use of underutilized species where appropriate, particularly species with populations that are increasing in response to climate change.

4.3. Implement programs that promote BMPs and/or sector-led initiatives to help protect and restore the ecological integrity of Lake Simcoe and its watershed.

4.4. Increase visitor awareness of climate change impacts on the watershed’s natural assets.

5. Agriculture

Vulnerabilities

The Lake Simcoe watershed contains some of the most productive agricultural land in Ontario, including the Holland Marsh. These lands are also close to large urban markets.

Extreme weather events, such as drought and hail storms, as well as increased potential for pest infestations have the potential to significantly affect farmers (Natural Resources Canada, 2007). For example, with milder temperatures, many pests and diseases, that were previously unable to over-winter and/or those able to extend their ranges northward into the watershed, pose a threat to food production and the economy (Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan).

Changes to the water cycle could affect water supply and availability for irrigating crops or raising livestock and other uses. On the other hand, a warmer and longer growing season may benefit farmers, including reduced heating bills for livestock barns, a longer growing season, and opportunities to grow and market new crops.

Strategic actions

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should support sustainable agriculture:

5.1. Support the Environmental Farm Plan Program and promote agricultural BMPs, including, among others:

- Protection of farmland , forests and wetlands;

- Crop rotation, reduced tillage, and rotational grazing;

- Nutrient and manure management;

- Water conservation; and

- Innovative designs for agricultural drains that reduce cropland runoff.

5.2. Collaborate with local partners at the Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority (LSRCA), the Dufferin Simcoe Land Stewardship Network (DSLSN), and the Lake Simcoe Stewardship Network (LSSM); and

5.3. Conduct and support research into sustainable and innovative methods of agricultural production.

6. Infrastructure

Vulnerabilities

Anticipated population growth will add to the complexity of assessing risks posed by climate change. Substantial development and infrastructure has been constructed in the Lake Simcoe watershed over the past number of decades that includes homes and commercial buildings, temporary and permanent roads, bridges, stormwater drainage systems, drinking water and water treatment services, hydro transmission lines, communications lines, and natural gas pipelines. This infrastructure is susceptible to deterioration caused by ongoing and long-term climate change, including more frequent extreme weather events.

For example, weather-related impacts on roads can range from non-catastrophic events resulting in cracked concrete and asphalt during freeze-thaw cycles to catastrophic flooding and road washouts. Increased frequency of higher-intensity (but non-catastrophic) storm events may contribute to water inflow and infiltration to sanitary sewers. This results in sewer back-ups and basement flooding. Increased water volumes from more frequent storm events can also affect sewage treatment capacity.

Sewage treatment plants are essential to communities and industry, as they treat sewage that would otherwise impair water quality and contribute excessive amounts of nutrients, pathogens, pollutants and sediment to the Lake Simcoe watershed.

Managing for climate change is an ongoing process rather than a one-time task, which can be accomplished by incorporating climate change protective measures into all levels of infrastructure planning and management.

Local agencies and the development community who are successful in making climate change adaptation considerations into their business practices will create a more robust and sustainable infrastructure system for Lake Simcoe communities over the long-term.

Strategic actions - business operations

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should formally recognize and incorporate climate change and adaptation strategies in their business operations and provision of services.

6.1. Assess risks to municipal services and infrastructure that may impact conservation and sustainability of water resources.

6.2. Develop plans to prioritize and address at-risk infrastructure.

6.3. Develop emergency management strategies to help communities prepare for increased flooding, drought and erosion due to a growing incidence of extreme weather events.

Strategic actions - design standards

All partners, in collaboration with the Province, should continue to use new design standards and protocols to mitigate the impacts of climate change and, where possible, to mimic natural processes in the planning, design and retrofitting of built infrastructure systems.

6.4. Continue to integrate climate change considerations into land use planning tools at the local level that support: low impact development; “green infrastructure”; water conservation; energy efficiency; sustainable transportation options; and improved air and water quality through such mechanisms as site plan control or a development permit system.

6.5. Continue to update manuals and guidelines, including municipal by-laws, to reflect climate change mitigation and/or adaptation options, including, but not limited to, infrastructure considerations.

Showcasing successes

Working with stakeholders across the watershed there are many collaborations resulting in climate change adaptation and mitigation actions. Building on previous research and actions, while complementing current priorities, including Ontario’s Climate Change Action Plan, we are continuing to protect and restore the health of Lake Simcoe.

These vignettes provide examples of how partners are working towards addressing the Strategic Actions.

Remote sensing of phosphorus across terrestrial landscapes

Who: In partnership with the St. Lawrence River Institute of Environmental Sciences.

What: The objective of this project is to improve knowledge of contributions and movement of non-point sources of nutrients. Nutrients from non-point sources challenge the accuracy of water quality models, as testing and monitoring for them is either difficult or financially prohibitive. Remote sensing provides a continuous picture of actual nutrient concentrations, rather than relying on extrapolation of point data. By understanding non-point source nutrient movements more accurate models and better estimates of how nutrient loadings to the lake will change under different climate change scenarios can be developed.

Where: Pefferlaw Creek / Uxbridge Brook subwatershed and the Beaver River subwatershed.

Why: Clean water is critical to both human and ecological well-being. Stresses from urban, rural, recreational and agricultural activities in the Lake Simcoe watershed have changed the landscape, vegetation, and ecological functions of the watershed and contributed to increases in the inputs of pollutants. Although the extent of the impact of climate change on water quality is uncertain, it is projected that it will influence the frequency, intensity, extent and magnitude of existing water quality problems. One of the critical objectives of the Plan is to reduce loadings of phosphorus and other nutrients of concern to Lake Simcoe and its tributaries to help improve water quality. As well, one of the key recommendations resulting from the Five Year Review of the Phosphorus Reduction Strategy (PRS) is to improve assessment of non-point source nutrient loading within the watershed.

When: The project began in 2016 and continues to 2018.

Next Steps: The results of this Project will be presented at a scientific meeting and be submitted as a manuscript to a scientific journal.

Supports: Strategic Action #1 - Aquatic life, shorelines and natural heritage and Strategic Action#2 – Water quality

Predictive modeling of forest carbon

Who: In partnership with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) and the University of Toronto (U of T).

What: Building on data collected since 2011, this project uses existing Vegetation Sampling Protocol (VSP) site level data to predictively model and map a number of indicators relevant to terrestrial monitoring and climate change

Where: Lake Simcoe watershed

Why: Natural heritage features are vital components of the ecosystem in and of themselves and are closely linked to other elements such as water quality and quantity. Climate change can influence the frequency, intensity, extent and magnitude of existing problems and cause impacts to natural areas such as change in species composition, shifts or loss of biodiversity within woodlands, riparian areas and wetlands and changes to forest cover and ecosystem functions in the watershed.

Natural cover, like forests and vegetation, absorb carbon dioxide, stores large amounts of carbon in living and dead biomass and in soils. Carbon storage helps to reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and reduce heat stress from evaporative cooling resulting in relatively low cost options to adapt and mitigate climate change.

Terrestrial vegetation, while critical to the Lake Simcoe ecosystem, is exposed to many stresses including land development, urbanization and habitat fragmentation. Monitoring vegetation can define when, where and to what extent these impacts are occurring.

When: Beginning in 2016 and going to 2018.

Next Steps: The results of this modeling will create wall-to-wall maps that represent mapped baseline conditions and can be used to spatially track changes in the watershed and determine proportions of high quality natural vegetative cover. Predictive monitoring can be applied to future samplings in the Lake Simcoe watershed and provide data to support an adaptive management approach to protecting the lake. Forecasting allows timely watershed management actions to be implemented that inform natural heritage system design and land use planning, such as green infrastructure, to adapt to climate change impacts.

Additionally, a summary paper of the predictive map application will be shared at regional, national and international conferences. A peer-reviewed, scientific article will be submitted to an ecological journal for publication.

Supports: Strategic Action#1 – Aquatic life, shorelines and natural heritage and Strategic Action #3 – Invasive species

Agricultural water use assessments in the Holland Marsh

Who: Farm & Food Care Ontario in partnership with Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) and the Holland Marsh Growers’ Association.

What: Water use assessments are being conducted to help farmers better understand how they use water. This includes water use optimization in food processing and irrigation and examining costs of production. Twenty on-site assessments, that assess current water uses using water meters and propose conservation measures, and water reuse and recycling options have been completed. By having better information, farmers are often able to reduce their water use, lower production costs, and adopt low cost water treatment systems.

Where: Agricultural businesses in the Lake Simcoe watershed

Why: Watershed users and residents depend on a sustainable water supply for a variety of uses, including drinking water, irrigation, food processing, navigation, recreation and wastewater assimilation. Climatic changes in water levels and flows such as larger precipitation events or heavy melts in the early spring and increased periods of drought during hot summer months, can affect water quantity and water quality, as well as, the health of natural areas and shorelines.

When: ongoing

Next Steps: Farm & Food Care Ontario continues to meet with farmers to offer advice and share the learnings from this project to help farmers makes good decisions on their water use.

Supports: Strategic Action#2 – Water quality and water quantity and Strategic Action, #5 - Agriculture

Modeling environmental flows (E-Flows)

Who: Partnership with the Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority (LSRCA)

What: In 2010, in collaboration with the Province and the University of Guelph (U of G), the LSRCA initiated work on in-stream flow targets. An outcome of that work was the creation of an in-stream flow target for the Maskinonge River, representing a low flow threshold for that water quantity stressed subwatershed. As a result of this work, the LSRCA published the Ecological Flows Guidance Document (2011) detailing the importance of managing environmental flows and the rationale for utilizing an e-flow framework for Lake Simcoe tributaries.

Each E-flow framework is unique to the subwatershed, with different types of channels, hydrologic features and flow regime. The modeling identifies whether high or low flow scenarios have a greater influence on the system. Information gathered from E-Flows modeling can be used to protect valued aquatic ecosystem components by providing resource manages information about changes in hydrology. This information can support selection of best practices for adapting to climate change in that particular subwatershed.

Where: Various subwatersheds in Lake Simcoe

Why: Activities in the watershed affect water quantity which can, in turn, significantly affect water quality. As demand for water continues to increase with growth and development, fluctuations due to climate change, such as variations in stream flow regimes and lake levels affecting fish, wildlife and aquatic habitats, are also occurring.

When: In 2016, LSRCA completed the evaluation of three development stressor states and ten climate change scenarios, informing the development of an E-flow framework in Lovers Creek, a subwatershed in Lake Simcoe.

In 2018, LSRCA will be completing an E-Flow framework for the East Holland River subwatershed. The results of this project will be shared with key stakeholders and posted on the LSRCA website.

Next Steps: An E-flow framework is a tool for use by water managers researching and monitoring ecological health in priority subwatersheds. Data collected informs management approaches to supporting climate change studies by comparing system flow equilibriums under stressors to hydrological features and functions in a tributary under different development scenarios and selecting best practices to manage rainfall can be captured at the source before being transported downstream.

Supports: Strategic Action#2 – Water quality and water quantity and Strategic Action #6 - Infrastructure

Valuing Lake Simcoe recreational fisheries

Who: Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF), in partnership with the Lake Simcoe Fisheries Stakeholder Committee, First Nations communities, and local interest groups.

What: MNRF performs open-water and winter angler surveys to track changes to Lake Simcoe’s recreational fisheries. Although most angling effort is documented in the winter season, ice cover has been variable in recent years, and there is a general trend in declining ice coverage. MNRF is adapting their monitoring programs to collect winter angler effort, catch, harvest and socio-economic data during ice-poor years. Analysis of this data facilitates anticipating possible shifts in seasonal angler effort, spring and fall recreational fisheries and the socio-economic impacts of these shifts on the recreational fishery

Where: Lake Simcoe watershed

Why: Healthy aquatic communities provide significant social and economic benefits, to communities in and around the Lake Simcoe watershed. Lake Simcoe experiences the highest fishing pressure of all inland lakes in Ontario and has become known as a ‘world-class’ ice fishing destination. Changing lake conditions as a result of a changing climate can have significant implications on recreational fisheries, in particular the coldwater fish community, and the associated socio-economic benefits.

When: ongoing

Next Steps: Adaptation strategies, such as promoting angling during open-water seasons to off-set any decline in the ice-fishing season and angling opportunities for lesser targeted species during the spring and fall seasons to help redirect effort otherwise experienced during the winter ice fishing seasons, are key to ensuring Lake Simcoe remains a top recreational fishing destination

Supports: Strategic Action#1 – Aquatic life, shorelines and natural heritage and Strategic Action #4 – Recreational activities

Enhancing our ability to adapt

Communication, engaging the community, and improving knowledge through research and monitoring are practices that will guide our efforts to implement the Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and will enhance our ability to adapt by keeping it current.

Informational products

Many adaptation tools and information have already been developed to assist local communities. MNRF has developed an online climate change adaptation toolbox to support the development of vulnerability assessments and adaptation actions.

Through the Community Adaptation Initiative, the MOECC provided funding to the Ontario Centre for Climate Impacts and Adaptation Resources (OCCIAR), who worked in partnership with the Clean Air Partnership to coordinate the development and collection of tools and information on climate change and make them publicly available at the Ontario Centre for Climate Impacts and Adaptation Resources website

Community of practice

A web-based interactive community of practice has been developed to support adaptation planning in the Lake Simcoe watershed by providing information, resources and support to individuals and organizations involved in adaptation planning. The resources provided helps users understand the adaptation measures identified in each of the Strategic Actions and provides guidance for adaptation activities within local communities. It also provides a space where researchers, experts and practitioners from across the watershed can come together to ask questions, generate ideas, share knowledge, and communicate with others working in the field of climate change adaptation.

Comprehensive monitoring strategy

Management of the Lake Simcoe watershed must be adaptive in the face of changing climatic conditions. A vigorous monitoring program that provides frequent feedback will be the key to future success. We can better understand the implications of climate change by continually tracking indicators of change over many decades in aquatic and terrestrial systems and evaluating ecological conditions across the watershed. It is important that both the Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan respond to the lessons learned from ongoing monitoring, research and modelling.

Plan Policy 7.11 called for an integrated climate change monitoring program, “…to inform decision-making and model the impacts of climate change on the watershed.” The Comprehensive Monitoring Strategy (CMS), which was released in March, 2015, states that information on many key ecological climate change indicators has been collected as part of provincial and partner long-term monitoring programs. The CMS recommended that monitoring of these indicators should be continued, and some additional high priority monitoring should be re-initiated (e.g., seasonal timing of lake trout spawning). It was also recommended that, because the effect of climate change expands beyond the Lake Simcoe watershed, where possible climate change monitoring should be standardized across other watersheds.

Conclusion and moving forward

The Province recognizes that a road map for restoring and protecting the health of Lake Simcoe must incorporate a strategy to adapt to climate change. This collaborative approach builds on the extensive actions that have taken place to date and is a catalyst for continued climate change adaptation and mitigation in the Lake Simcoe watershed ensuring the long-term health of the lake and all who rely on it.

To move the Lake Simcoe Climate Change Adaptation Strategy forward, the Province will:

- Engage local governments (e.g., municipalities and First Nation/Métis communities), community partner agencies, the development community (e.g., planning authorities and developers), businesses, citizens, and interested stakeholders;

- Continue to collaborate with partners on supporting actions to assist with strategy implementation;

- Encourage development of implementation plans and schedules that identify roles, responsibilities, and timelines to support the integration and delivery of adaptation activities described in the six Strategic Actions;

- Oversee implementation of the comprehensive monitoring strategy and host biennial Lake Simcoe Science Forums to discuss scientific results and collaborate on monitoring and research; and

- Continue to collaborate with partners and promote stewardship actions across the watershed enabling new ideas and approaches.

Appendix A – Development of the Lake Simcoe climate change adaptation strategy

There are many policies in the Plan designed to protect the ecosystem. Many of them simultaneously assist with climate change adaptation by supporting actions including conducting research, carrying out monitoring, and developing strategies and guidelines. Some of these supporting actions are further highlighted in Appendix A of this strategy.

The development of this strategy was supported by the Province’s Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation. Appointed in 2007, the Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation was created to advise the Province on how best to protect our health, environment, infrastructure and economy from the effects of climate change in Ontario. This multi-disciplinary panel was comprised of leading scientists, industry representatives and environmental experts. In 2009, the Panel released a report containing 59 recommendations, including: “the climate change adaptation strategy called for in the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan should be considered as a pilot project with potential application to strategies for increasing the climate resilience of other watersheds.” (Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation, 2009).

Recommendations provided by the Lake Simcoe Science Committee on how to adapt to climate change were included in the Committee’s June 2012 report to the Minister of the Environment. Many of the issues identified are reflected in this strategy.

The tasks laid out in the Plan are:

- Assess and evaluate the risk of climate change impacts on the watershed;

- Promote, conduct and support additional research to better understand the impacts of climate change in the watershed, including impacts on wetlands, aquatic life, terrestrial species and ecosystems, headwaters, conservation of life cycles, groundwater temperature, and water table levels;

- Develop an integrated climate change monitoring program to inform decision making and model the impacts of climate change on the watershed; and

- Begin the development of climate change adaptation plans and promote the building of a Lake Simcoe watershed community of practice in adaptation planning.

Progress to date includes assessing and evaluating risks through Vulnerability Assessments, conducting various research projects, creating an online Community of Practice to encourage practitioners to share information and support the integration of climate change adaptation into decision-making, and releasing a comprehensive monitoring strategy that addressed climate change-related ecological and environmental monitoring.

Strategy development

Adapting to the impacts of climate change requires increasing the watershed’s resilience to and promoting behavioral change to meet current and emerging challenges. An adaptive approach to management, that allows for continual monitoring of a selected approach and subsequent adjusting of that approach in order to achieve desired outcomes, is key to achieving these objectives.

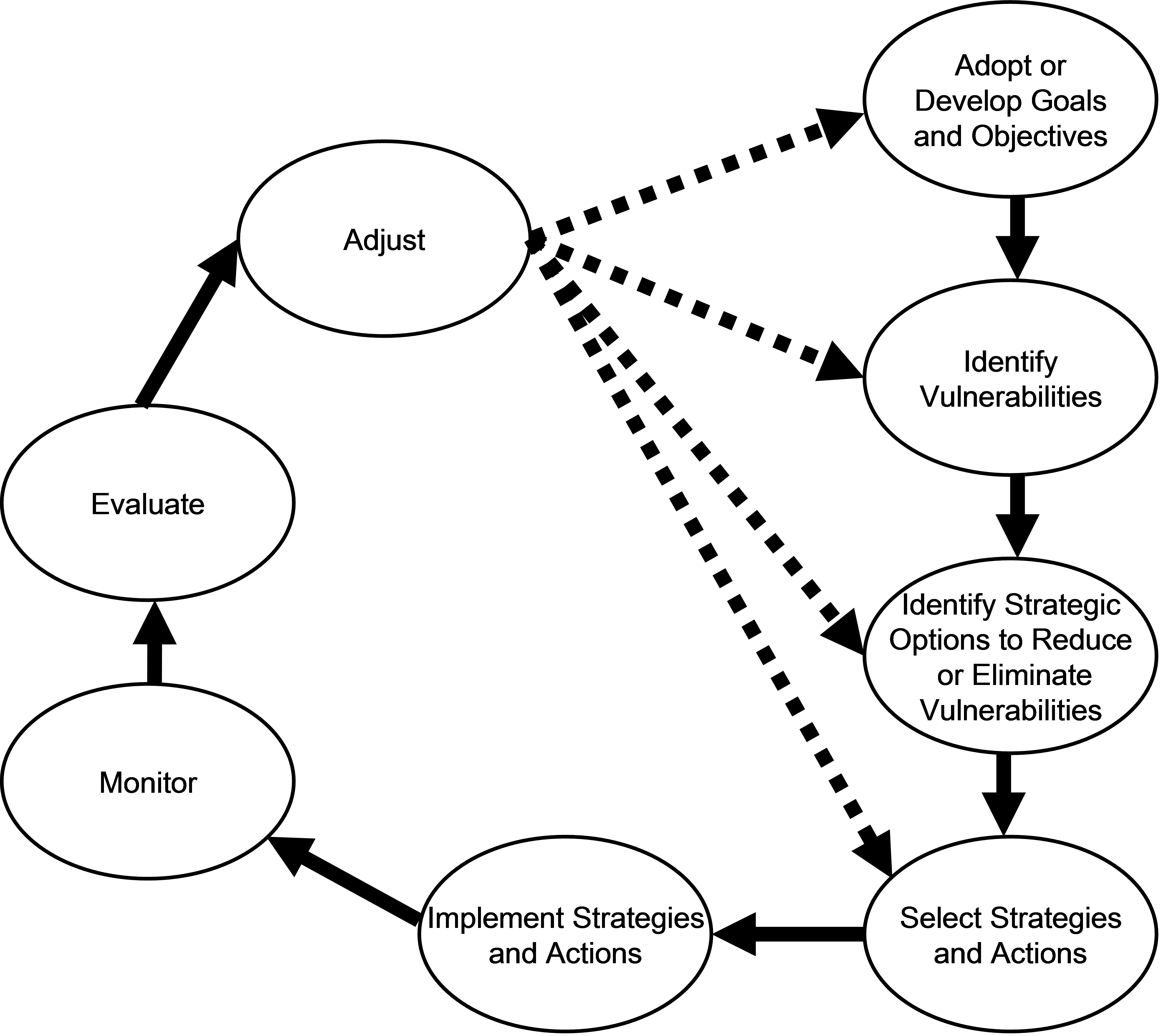

Figure 4

Indicators are scientific variables that help to simplify large amounts of complex information. They are a guide used to determine the level of environmental quality or health, e.g., dissolved oxygenand phosphorus concentrations are often used to characterize and communicate the condition or health of a lake to the public (adapted from Lake Simcoe Science Advisory Committee report).

Following the advice in Climate Ready, an adaptive management process was used to inform the development of this strategy and will be the basis for its continual evaluation. This process involves setting or adopting existing goals (i.e., establishing targets), identifying strategic options available to meet the goals using vulnerability analyses and other techniques, implementing selected strategies (e.g., protection and rehabilitation), monitoring the success of the strategies (i.e., using indicators to measure progress) and modifying them as necessary (Figure 1). In addition, it is important that decision makers understand and manage for the other stressors (e.g., pollution) that also impact the watershed. Therefore, the adaptive management cycle must also consider the cumulative impacts of multiple stressors on the health and well-being of the watershed and the people who live, work and vacation there.

The development process for the strategy involved six steps:

- Identified sectors and indicators (e.g. hydrology, wildlife, infrastructure);

- Completed current vulnerability assessments of the sectors using the indicators;

- Projected potential future climate scenarios;

- Completed future vulnerability assessments of the sectors using the indicators;

- Developed adaptation options; and

- Selected adaptation strategies and associated actions.

Scientists and practitioners were engaged to complete vulnerability assessments for each sector using indicators that quantitatively or qualitatively provide decision-makers with information about how a natural asset (e.g., fish species), a system (e.g., a lake ecosystem, climate) or human asset (e.g., municipal stormwater infrastructure) is threatened, changing or will potentially change as a result of projected climate change.

An example of an indicator is the condition of the coldwater fishery, which is used to provide an expression of the overall health of the aquatic ecosystem. The details of the relationship between the indicators and the natural asset are usually quite complex. The potential impact of climate change on the coldwater fishery could be described as follows: as excessive phosphorus leads to increased plant growth, including algae, the decomposition of these plants leads to the depletion of dissolved oxygen in the deep waters of the lake and degradation of critical habitat required by coldwater fish species. Climate change may increase phosphorus loading to Lake Simcoe and impede the recovery of the coldwater fishery. Increased runoff and erosion resulting from storm events may cause added sediment to accumulate in the spawning beds. Warmer air temperatures and reduced ice cover would further extend the time that the deep waters of the lake are not mixing with the surface waters during the summer. This may, in turn, enhance the dissolved oxygen limitation and limit the seasonal coldwater fish habitat.

Vulnerability Assessments for all sectors/themes can be accessed on the OCCIAR website: www.climateontario.ca, under OCCIAR Projects – Lake Simcoe. Observations resulting from vulnerability assessments were used to identify adaptation options and inform discussions and feedback towards creation of this Strategy.

The Province convened a forum of climate change experts to develop adaptation options during two workshops and through a follow-up questionnaire. In addition, meetings were held to solicit advice on climate change adaptation ‘best practices’ already underway within the watershed or being undertaken by other jurisdictions. Vulnerabilities identified through this process are described below and followed by Strategic Actions to address the respective vulnerabilities.

In tandem with these efforts, the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation (CGIFN) and the OCCIAR have been undertaking a climate change adaptation planning exercise in order to raise awareness of, and manage, climate change risks on Georgina, Snake and Fox islands within Lake Simcoe. The adaptation planning process was founded on a comprehensive framework that was first developed for use on Georgina Island in Lake Simcoe. This framework included facets of team building, a survey of traditional ecological knowledge, data collection, vulnerability and risk assessments, adaptation action and implementation planning, and mainstreaming adaptation into band policies. Fundamental to the entire process has been community engagement and an oversight committee of advisors from the community.

In 2016 the province provided funding to CGIFN to support the First Nation communities of Beausoleil and Rama and their efforts to adapt to climate change and mitigate impacts to lands and waters including those in the Lake Simcoe watershed.

Appendix B – Summary of supporting actions

Significant work has already taken place towards completing the tasks laid out in the Strategy. Supporting actions already completed or underway are summarized below:

Aquatic life, shorelines and natural heritage

1.1. Develop explicit terrestrial, aquatic, and rehabilitation targets to restore and maintain ecological integrity and ecosystem function in the watershed (e.g., set threshold targets for minimum forest cover and minimum stream base flows).

- Fish Community Objectives (FSO) have been established to guide the development of rehabilitation targets and inform management decisions about the Lake Simcoe fisheries.

- A minimum of 40 per cent high quality natural vegetative cover is a target for the Lake Simcoe watershed, with no further loss of natural shorelines.

- Vegetation Sampling Protocol (VSP) was selected as a preferred approach to site-level terrestrial monitoring for the Lake Simcoe watershed. Indicators were developed and three years of VSP implementation was piloted.

- Landscape-scale terrestrial habitat was mapped using ortho-photography and the Lake Simcoe shoreline was characterized (e.g. natural versus altered) using oblique aerial photography. Photography provides information regarding baseline conditions, so changes can be tracked over time.

1.2. Support, promote and implement restoration programs in both built and natural areas by planting a diverse mix of indigenous tree species, including those expected to be better adapted to climate change, and maintain high levels of genetic diversity to reduce vulnerability to climate change impacts.

- Priority areas for riparian restoration have been mapped, including corridors, which guide decisions on where to focus restoration efforts.

- Ontario’s Tree Atlas provides guidance on which species are native to the Lake Simcoe watershed and are best suited to support restoration activities.

1.3. Maintain and improve functional stream corridors by reducing impacts from on-line ponds, barriers to fish movement where appropriate, and other factors that can alter the stream thermal regime.

- Technical papers on guidance for natural heritage evaluations and definitions of key natural heritage and key hydrologic features have been released to facilitate interpretation and application of the natural heritage policies of the Plan.

- A "Shoreline Management Strategy" is under development to guide restoration activities by identifying ecological values, BMPs, guidelines and priority areas for restoration.

- Two companion resources have been released, “Along the Shore: A Landowner’s Guide to Healthy Shoreline Management for Lake Simcoe” and “Working Along the Shore: A Professional’s Guide to Healthy Shoreline Management for Lake Simcoe” to promote shoreline re-naturalization.

Water Quantity

2.1. Develop and implement water sustainability plans for municipal water services, including water conservation plans, an assessment of risks to future delivery of municipal services and plans to deal with those risks, as recommended for specific municipalities in Plan Policy 5.3.

- All municipalities referred to in Plan Policy 5.3 have Water Conservation Efficiency Plans (WCEPs) or water conservation programs in place.

- The Water Opportunities Act (WOA) sets the framework to help municipalities improve the efficiency of municipal infrastructure and services particularly with respect to water sustainability and conservation plans. The Act acknowledges climate change impacts and specifies where there are such risks, a plan be put in place to deal with them.

2.2. Use adaptive management practices to ensure that water levels can be maintained and managed sustainably in response to changing climatic conditions.

- With provincial support, the LSRCA has completed water budget studies and stress assessments for every subwatershed in the Lake Simcoe basin resulting in groundwater flow models that help improve water resources management activities. These water budgets provide necessary information for subwatershed planning.

- The LSRCA is working with the province to map ecologically significant groundwater recharge areas. These are areas that provide water to ecologically-significant features, such as coldwater streams and significant wetlands. Areas of high volume recharge have been mapped for the entire watershed. In early 2014, the LSRCA, together with MNRF, the ministry, and with input from watershed municipalities, developed guidance for managing ecologically significant groundwater recharge areas to assist municipalities in protecting and restoring these important areas during times of changing climatic conditions.

2.3. Reduce dependence on traditional groundwater and surface water resources through use of alternative water sources, such as rainwater and greywater, and Low Impact Development (LID) techniques and green infrastructure.

Encouraging LID provides options to manage water quality and water quantity issues which can start on individual properties using design features that manage runoff as much as possible, then at a broader scale, includes a treatment technology in the watercourse to deal with excess runoff. The result is a community that is more resilient to the effects of climate change and has more native landscaping and green space.

- The Plan promotes greater efforts to conserve and use water more efficiently in order to maintain future demands for water within sustainable limits. York Region’s “Water for Tomorrow” program offers residents information and rebates on selected water-saving appliances for businesses. Since 1998, York Region residents have saved 26 million litres of water per day with the support of the Water for Tomorrow program.

- A number of LID demonstration projects have been implemented in the Lake Simcoe Watershed that showcase LID implementation as a viable solution to managing stormwater runoff close to the source, improving water quality and achieving stormwater management (SWM) control to adapt to changing climatic conditions.

Water Quality

2.4. BMPs on land use to manage urban, rural and agricultural runoff and nutrient loading.

- All partners continue to develop and promote BMPs to support good stewardship in the agricultural and other interested sectors. The "Lake Simcoe Stewardship Guide" helps identify BMPs that will improve area water quality and the surrounding natural landscape.

- Specific complementary actions that help protect water quality include:

- implementation of the PPRS to ensure the long-term protection of the lake, watershed, and ecosystem by reducing the phosphorus loads;

- continuing to promote, conduct and support water quality research projects;

- approval of Source Protection Plans under the Clean Water Act (CWA) to enable Ontario communities to effectively protect their drinking water sources against threats, including climate change; and

- development and implementation of Subwatershed Plans to guide local restoration efforts, led by the LSRCA with support from the province and in collaboration with watershed municipalities.

2.5. Develop joint programs through public/private partnerships that may include cost-sharing for innovative initiatives, such as rainwater harvesting, green roofs and greywater reuse.

- LSRCA is working with municipalities and the development community to encourage the adoption of new technologies (such as rain gardens and permeable pavement) that have proven effective at managing water on site, with the goal of adopting these innovative technologies in all new communities in the watershed.

2.6. Integrate climate change adaptation considerations and BMPs into manuals and guidelines available to people working in agriculture, land use development and other sectors.

- Credit Valley Conservation (CVC) has developed a collection of LID publications and guidance documents highlighting the process and BMP tools for innovative SWM that are applicable in the Lake Simcoe watershed.

Invasive Species

3.1. Research cumulative impacts and interacting stressors related to invasive species in the watershed.

- MNRF is working with local partners to employ innovative research techniques and new technology to understand and assess the health of the aquatic communities of Lake Simcoe. MNRF has conducted baseline mapping of all known aquatic habitats, and has used hydroacoustics to learn how invasive species and climate change have impacted the offshore aquatic community.

- MNRF is undertaking research to identify high-risk areas and pathways for invasive species and developing outreach/education targeting these pathways.

3.2. Develop prevention, early detection and management approaches for aquatic and terrestrial invasive species.

- The Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan, 2012 provides a comprehensive, coordinated framework to prevent, detect, respond to and manage invasive species and may be a helpful reference guide in the development of new plans and approaches.

- The Province is collaborating with public bodies to adapt and/or develop the risk-based response plans identified above for priority invasive species.

- A watch list has been developed for terrestrial and aquatic invasive species indicating those likely to be introduced into the Lake Simcoe watershed.

3.3. Develop risk-based response plans for harmful invasive species.

- The Invasive Species Act, 2015, sets out a legislative framework that provides for the identification of invasive species that threaten Ontario’s natural environment including mechanisms for detecting the introduction of invasive species and bringing them within the legislative framework as quickly as possible after they are observed. In addition, the Act invokes inspection powers and other provisions that will work to prevent the introduction of, control the spread of, and to remove and eradicate invasive species in Ontario and the Lake Simcoe watershed.

- Complementary actions that protect against invasive species include the Biodiversity Plan which identifies over 100 activities and actions the province will undertake with industry, environmental and community partners over the next decade to protect biodiversity (actions and activities include assessing species and ecosystem vulnerability to climate change, integrating vulnerabilities into decision-making, and implementing the Plan).

Recreational Activities

4.1. Diversify attractions and destinations to offset demand for and/or losses to tourism and recreational activities, such as boating, snowmobiling and fishing, which may be affected by climate change.

Nature-based recreation opportunities including swimming, fishing and camping in the Lake Simcoe watershed attract thousands of residents and visitors. Climate change influences participation in nature-based recreation as recreational use is strongly correlated to climate. Climate influences water quality, snow cover and wildlife that combine to provide the outdoor recreational experience and influence the level of personal satisfaction (Jones and Scott, 2006). Given that the Lake Simcoe watershed provides significant opportunity for nature-based recreation, changes in climate and corresponding changes in ecosystem composition, structure and function will require shifts in human activities.

- FSO, are an adaptive management tool that has been developed in the context of stressors acting on the fish populations in the lake. These stressors include climate change and invasive species, which will be revisited as new information becomes available.

- MNRF performs open-water and winter angler surveys to track changes to Lake Simcoe’s recreational fisheries, which consider climate change as part of the analysis. In order to anticipate possible shifts in seasonal angler effort and resulting fisheries management, MNRF monitored spring and fall recreational fisheries in 2015.

- The Province and its partners continue to support and promote environmentally sustainable recreation and tourism practices focused on promoting environmental sustainable recreational activities. Examples include:

- Clean Marine in the Lake Simcoe watershed that requires marinas to follow environmentally-sound marine operation practices to achieve certification.

- With support from the province in 2016, the Ontario Boating Association is continuing to encourage recreational boaters to adopt clean boating practices.

- The Province provided funding to Ryerson University to examine the impact of festivals and large events in the Lake Simcoe watershed including gauging visitor interest in environmentally sustainable tourism in the watershed, and demonstrating the benefits of sustainable practices to festival organizers.

- Collaborating festivals included the Mariposa Folk Festival and ‘Brock Big Bite’ festival, which bring thousands of visitors to the area. The project promoted best practices to reduce waste, water and energy inputs and outputs, encouraged the use of local products in supply chain, and provided learning opportunities for guests and vendors.

4.2. Ensure the sustainability of fishing effort on coldwater species, recognizing that climate change may cause additional stress on these populations. Promote the use of underutilized species where appropriate, particularly species with populations that are increasing in response to climate change.

- MNRF in partnership with the Lake Simcoe Fisheries Stakeholder Committee, First Nations communities, and local interest groups performed a valuation of the fishery and aquatic community within the Lake Simcoe watershed through an analysis of the socio-economic benefits. Scenarios were built to identify measures to increase climate resilience of Lake Simcoe’s aquatic ecosystem.

4.3. Implement programs that promote BMPs and/or sector-led initiatives to help protect and restore the ecological integrity of Lake Simcoe and its watershed.

- Collaborative programming is underway between MNRF and Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation (CGIFN) to restore wild rice, an aquatic plant native to Lake Simcoe. Bringing back a native component of aquatic biodiversity will improve the resiliency of Lake Simcoe and may allow future harvest opportunities to CGIFN.

- Also being restored and enhanced in the Lake Simcoe watershed are shoreline habitats, re-vegetation of buffer zones around tributaries, and the re-introduction of a top predator, Muskellunge.

4.4. Increase visitor awareness of climate change impacts on the watershed’s natural assets.

- Green Tourism Toolkits were developed with support from the province, Tourism Barrie, and in collaboration with Regional Tourism Organization 7 and Ryerson University, developed a series of Green Tourism Toolkits. Each toolkit provides a list of practical steps for tourism operators to take to make their business sustainable and more resilient to climate change such as encouraging adoption of best practices for reducing energy use, carbon output, water use and waste. To date more than 500 business operators have engaged with the Project staff.

Agriculture

5.1. Support the Environmental Farm Plan Program and promote agricultural BMPs, including, among others:

- Protection of farmland, forests and wetlands;

- Crop rotation, reduced tillage, and rotational grazing;

- Nutrient and manure management;

- Water conservation; and

- Innovative designs for agricultural drains that reduce cropland runoff.

- Continuing to support the Canada-Ontario Environmental Farm Plan Program where Environmental Farm Plans are voluntarily prepared by farm families to increase their environmental awareness and reduce risks in almost all areas of their farm operations.

5.2. Collaborate with local partners at the LSRCA, the DSLSN and the LSSM.

- Continuing to develop and promote agricultural BMPs to support good stewardship and help farmers implement sustainable farm projects through demonstrations, pilot projects and programs.

5.3. Conduct and support research into sustainable and innovative methods of agricultural production.

- Continuing to promote, conduct and support research projects to optimize nutrient management that build on existing research and monitoring programs, identify emerging issues, and inform adaptive management to address climate change impacts.

Infrastructure - business operations

6.1. Assess risks to municipal services and infrastructure that may impact conservation and sustainability of water resources.

- Improving the capacity of owners of SWM works within the Lake Simcoe watershed, to adopt best practices for inspection, maintenance and record keeping.

- Enhancing knowledge about the response/vulnerability of selected stormwater ponds to predicted climate change impacts such as increased summer temperatures, increased number of zero degree days in winter and increases in intense precipitation events.

6.2. Develop plans to prioritize and address at-risk infrastructure.

- Guidelines have been developed in collaboration with the LSRCA to assist municipalities in developing and implementing Comprehensive Stormwater Management Master Plans. All watershed municipalities have initiated the development of their master plans, and several have initiated their implementation.

- Complementary actions that also protect against risks to infrastructure include:

- Implementation of Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan which outlines the Province’s strategy and actions to address the impacts of a changing climate over the next four years as Ontario prepares for the risks and opportunities created by a changing climate, including risks to infrastructure.

- Building Together, the Province’s long-term infrastructure plan includes a requirement that asset management plans be prepared by the Province or transfer payment partners to show how climate change adaptation was considered in the project design.

- Release of the Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) 2014 includes new policies for municipalities to plan their communities in a “manner that considers impacts from climate change”- in relation to both mitigation and adaptation. This will help municipalities plan in a manner that both reduces greenhouse gases and creates more resiliency to the impacts of a changing climate.

- Consultations for the Co-ordinated Land Use Planning Review of four provincial plans (Niagara Escarpment Plan (NEP), Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan (ORMCP), Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GPGGH) and the Greenbelt Plan (GP)) were conducted in 2015. One of the key recurring themes which emerged during the consultations was integrating climate change into the plans.

6.3. Develop emergency management strategies to help communities prepare for increased flooding, drought and erosion due to a growing incidence of extreme weather events.

- Information is made available to the public through the Flood Forecasting and Warning Program and conservation authorities carry out programs that serve provincial and municipal interests including managing natural hazards, flood and erosion, ice management, flood forecasting and warning, and the drought / low water program.

Infrastructure - design standards

6.4. Continue to integrate climate change considerations into land use planning tools at the local level that support: LID; “green infrastructure”; water conservation; energy efficiency; sustainable transportation options; and improved air and water quality through such mechanisms as site plan control or a development permit system.

- Support new infrastructure design through the continued promotion and support for research projects to identify new and innovative SWM (e.g., in partnership with the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, the LSRCA is currently evaluating a number of promising phosphorus reduction technologies).

- The provincial program ‘Showcasing Water Innovation’, demonstrates leading edge, innovative and cost-effective solutions for managing drinking water, stormwater and wastewater systems in Ontario communities. The program complements Ontario’s WOA by fostering innovation, creating opportunities for economic development, and protecting water resources.

- With support from the province, the LSRCA is supporting municipalities and developers with overcoming the barriers to adopting LID solutions at new and retrofit project locations within the Lake Simcoe watershed.

- Nine LID projects have been initiated in the Lake Simcoe watershed through LSRCA’s RainScaping program with funding support from Environment Canada and Climate Change.

- Training is available for developers and approval agencies on LID and for municipalities interested in implementing LID on municipal lands.

6.5. Continue to update manuals and guidelines, including municipal by-laws, to reflect climate change mitigation and/or adaptation options, including, but not limited to, infrastructure considerations.

- With support from the province, LSRCA is undertaking work to enhance knowledge about SWM ponds in the Lake Simcoe watershed and the anticipated impacts of climate change through three research projects on (1) maintenance and inspection practices, (2) the effects of road salt transport on SWM ponds, and (3) evaluating the vulnerability of selected SWM ponds

- LSRCA’s Board of Directors approved changes to the Watershed Development Guidelines to align with the Plan and address climate change considerations and impacts.

- The LSRCA’s SWM guidelines are also being revised to encourage better site design techniques including preservation of natural areas, reduced impervious cover, distributed runoff and use pervious areas to more effectively treat stormwater runoff.

References

Banuri, T., K. Goran-Maler, M. Grubb, H.K. Jacobson and F. Yamin (1996). Equity and social considerations. Climate Change 1995: Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, J.P. Bruce, H. Lee and E.F. Haites, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Douglas, A.G., C. Lemieux, G. Nielsen, P.A. Gray, V. Anderson and S. MacRitchie. 2011. Adapting to Climate Change -- Tools and Techniques for an Adaptive Approach to Managing for Climate Change: A Case Study. Ontario Centre for Climate Impacts and Adaptation Resources (OCCIAR), 935 Ramsey Lake Road, Sudbury, Ontario, P3E 2C6. Unpublished Report. 66p.

Hunt, A. (2010). National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy: Economic Risks and Opportunities of Climate Change for Canada: Technical Guidance for “Bottom-up” Sectoral Studies. http://nrtee-trnee.ca/climate/climate-prosperity

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). Glossary of terms used in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (WG I; WG II; Glossary of Synthesis Report).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis.

Jones, B., and D.J. Scott (2006). Implications of climate change for visitation to Ontario‘s provincial parks. Leisure, 30(1):233-261.

Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Ministry of the Environment. Lake Simcoe Protection Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2009.

Lake Simcoe Science Advisory Committee. Lake Simcoe and its Watershed: Report to the Minister of the Environment. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2008.

Lake Simcoe Science Advisory Committee. Lake Simcoe and its Watershed: Report to The Minister of the Environment. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2012.

Lal, R., J.A. Delgado, P.M. Groffman, N. Millar, C. Dell and A. Rotz (2011). Management to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 66(4):276-285.

Leal, D., K. Pinkerton, K. Landman, W. Caldwell, E. McGauley, J. Hancock, D. van Hemessen and J. Klug. Lake Simcoe Stewardship Guide. University of Guelph and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources: Canada, 2009.

Oke, T.R. (1973). City size and the urban heat island. Atmospheric Environment, 7:769-779.

Ontario Biodiversity Council and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy: Protecting What Sustains Us — Renewing Our Commitment, 2011.

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs. Canada-Ontario Environmental Farm Plan, 2016.

Ontario Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. Simcoe Area: A Strategic Vision for Growth 2009. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2009.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment. Climate Action: Adapting to Change, Protecting Our Future. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2011.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment. Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan, 2011-2014.Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2011.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment. Lake Simcoe Protection Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2010.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment. Lake Simcoe Phosphorus Reduction Strategy. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2010.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment. Minister’s Annual Report on Lake Simcoe 2010.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment (2010). Fact Sheet: Protecting Ontario’s Waterways in a Changing Climate — Managing Stormwater.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (2015). Lake Simcoe Monitoring Report, 2014.

Ontario Ministry of Finance. Ontario Population Projections Update, 2005 – 2031: Ontario and Its 49 Census Divisions. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2006.

Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Greenbelt Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2005.

Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, Ontario, 2002.

Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan, 2001.