11. Land use planning

Provincial Planning Statement, 2024

Ontario has released a new streamlined provincial planning document that will replace the Provincial Policy Statement, 2020 and A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe 2019, as amended in 2020.

Learn more about Provincial Planning Statement, 2024, which comes into effect on October 20, 2024.

Community or land use planning can be defined as managing our land and resources. Through careful land use planning, municipalities can manage their growth and development while addressing important social, economic and environmental concerns. More specifically, the land use planning process balances the interests of individual property owners with the wider needs and objectives of your community, and can have a significant effect on a community’s quality of life.

You have a key role to play in land use planning. As a representative of the community, you are responsible for making decisions on existing and future land use matters and on issues related to local planning documents.

It is important to note that land use planning affects most other municipal activities and almost every aspect of life in Ontario. Council will need to consider these effects when making planning decisions, while recognizing that most planning decisions are long-term in nature. Public consultation is a mandatory part of the planning process. You and your colleagues will devote a large part of your time to community planning issues. You may also find that much of your interaction with the public involves planning matters.

Good planning contributes significantly to long-term, orderly growth and efficient use of services. On a day-to-day basis, it is sometimes difficult to see how individual planning decisions can have such impact. Making decisions on planning issues is challenging and, for these reasons, it is important to understand the planning system and process.

The land use planning framework

The responsibility for long-term planning in Ontario is shared between the province and municipalities. The province sets the ground rules and directions for land use planning through the Planning Act and the Provincial Planning Statement (PPS). In certain parts of the province, provincial plans provide more detailed and geographically-specific policies to meet certain objectives, such as managing growth, or protecting agricultural lands and the natural environment. The Greenbelt Plan, Niagara Escarpment Plan (NEP), the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan (ORMCP), and the Growth Plan for Northern Ontario are examples of geography-specific regional plans. These plans work together with the PPS, and generally take precedence over the PPS in the geographic areas where they apply. While decisions are required to be “consistent with” the PPS, the standard for complying with these provincial plans is more stringent, and municipal decisions are required to “conform” or “not conflict” with the policies in these plans.

A note on references in the Greenbelt Plan

Any reference in the Greenbelt Plan to “the PPS” is a reference to the Provincial Policy Statement, 2020 as it read immediately before it was revoked and any reference to “the Growth Plan” is a reference to the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe 2019 as it read immediately before it was revoked.

Municipalities and planning boards implement the province’s land use planning policy framework. Municipalities and planning boards prepare official plans and make land use planning decisions to achieve their communities’ economic, social and environmental objectives, while implementing provincial policy direction. Municipal decisions must be “consistent with” the PPS, which means that municipalities are given some flexibility in deciding how best to achieve provincial policy direction.

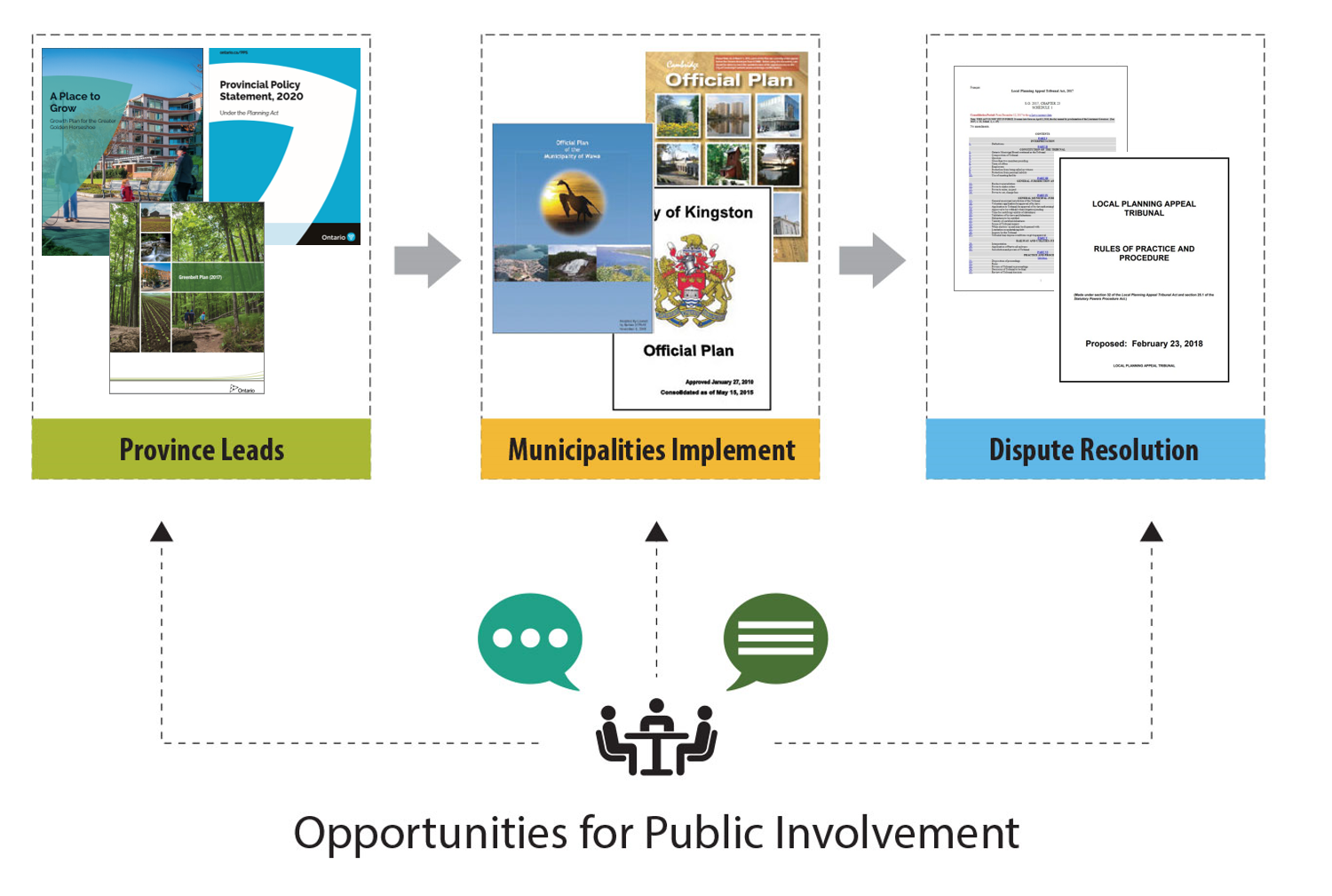

The diagram below shows the land use planning system and its main components from left to right:

- the province sets out the legislative framework and policies

- municipalities and planning boards are the primary decision makers and implement the policy direction through their official plans and zoning by-laws, and also through decisions on planning matters

- approval authorities and the Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT) provide dispute resolution mechanisms for protection of provincial interests and interests in individual land owners and proponents

Planning is fundamentally a public process. It includes the input of developers, residents, Indigenous communities and individuals to help municipalities achieve their goals and implement the provincial and municipal policy frameworks.

The following provides you with an overview of the responsibilities and roles of the main parties involved in the planning system:

The public:

- Early involvement in consultations/meetings

- Keep informed

- Provide input (for example, attend public meetings, express views on development proposals and participate in making policy)

Proponents/Applicants:

- Early consultation with municipality/approval authority

- Submit complete application

- Meeting provincial policy, official plan(s) and zoning requirements

- Community involvement

Municipal Council:

- Adopt up-to-date official plan

- Early consultation

- Decisions “shall be consistent with” PPS

- Public notice and meetings

- Engage with Indigenous communities

- Apply provincial and local interests

- Decision making on planning applications

- Defend decisions at the Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT)

- Measure Performance

The Province:

- Policy and statute development

- Approval authority for certain planning matters

- Engage with Indigenous communities

- Broad provincial/inter-regional planning

- Education and training

- Technical input

- Research and information

- Performance measures

Ontario Land Tribunal

- Appeal body for hearing and deciding appeals of planning matters

The Planning Act

The Planning Act is the basis of Ontario’s land use planning system. It defines the approach to planning, and assigns or provides the roles of key participants. All decisions under the Planning Act must follow provincial policy direction as set out in the PPS and provincial plans.

The Planning Act is the legal foundation for key planning processes such as:

- local planning administration

- the preparation of planning policies

- development control

- land division

- the management of provincial interests

- the public’s right to participate in the planning process

The Planning Act also sets out processes and tools for planning and controlling development or redevelopment. These tools include:

- official plans

- zoning by-laws (including minor variances)

- community planning permit systems

- land division (for example, plans of subdivision or consents)

- site plan control

- community improvement plan.

Decisions on land use planning documents and applications are the responsibility of the applicable authority. This can be different depending on your local circumstances and the type of planning document or application. Your municipal staff or planning board officials will advise you on which body is responsible for making decisions on different types of planning documents in your municipality or planning area. Note: In some situations municipalities may not have a dedicated planner on staff and may retain the services of a planning consultant/firm.

The Provincial Policy Statement

The Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) is issued under section 3 of the Planning Act and provides policy direction on matters related to land use planning that are of provincial interest (including those as set out in section 2 of the Planning Act).

The PPS provides the policy foundation for regulating the development and use of land in Ontario. The PPS includes direction on matters such as managing growth and new development, housing, economic development, natural heritage, agriculture, mineral aggregates, water and natural and human-made hazards.

Municipalities implement the PPS through their official plans, zoning by-laws and decisions on planning applications. The Planning Act provides that decisions made by councils exercising any authority that affects a planning matter “shall be consistent with” the PPS. This means that the PPS must be applied when making land use planning decisions and in developing planning documents, such as official plans and zoning by-laws. Every planning situation must be examined in light of the relevant PPS policies.

Local conditions should also be taken into account when applying PPS policies and when developing planning documents. The PPS makes it clear that planning authorities, including councils, are able to go beyond the minimum provincial standards in specific policies when developing official plan policies and when making planning decisions – unless doing so would conflict with another PPS policy or with a policy in a provincial plan (see below).

Provincial plans

The PPS provides the policy foundation for a number of provincial plans. As with the PPS, municipal official plans and zoning by-laws are the primary vehicle for implementing provincial plans. Decisions under the Planning Act (for example approval of official plans or plans of subdivision) must conform or not conflict with the applicable provincial plan in place.

Unlike the PPS, which applies province-wide, a number of provincial plans apply to particular areas in the province. They provide policy direction to address specific needs or objectives in the geographies where they apply – such as environmental, growth management and/or economic issues.

Provincial plans include:

- The Growth Plan for Northern Ontario is a framework to guide decision-making to support priority economic sectors and structured around six themes: economy, people, communities, infrastructure, environment and Indigenous peoples. The Growth Plan for Northern Ontario does not set population targets for municipalities. It lets municipalities determine intensification targets for growth and exactly where growth should occur.

- The Greenbelt Plan is issued under the Greenbelt Act, 2005 and provides policy coverage primarily for the protected countryside area by identifying and providing permanent protection to areas where urbanization should not occur. The plan provides policies for permanent agricultural and environment protection in the protected countryside area, supporting an agricultural and rural economy while also providing for a range of recreation, tourism and cultural opportunities. The Greenbelt Plan also includes an urban river valley designation to allow for Greenbelt protections to be provided within urban areas. The Greenbelt Act, 2005 provides for the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan and Niagara Escarpment Plan to continue to apply within their areas and stipulates that the total land area of the Greenbelt area is not to be reduced in size.

- The Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan (ORMCP): The Oak Ridges Moraine extends 160 km from the Trent River in the east to the Niagara Escarpment in the west and has a concentration of environmental, geological and hydrological features. It is the regional north-south watershed divide, and the source and location of the headwaters for most major watercourses in south-central Ontario. The ORMCP, approved as Minister’s regulation Ontario Regulation140/02 under the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Act, 2001, is an ecologically-based plan that provides direction for land use and resource management in the 190,000 hectares of land and water in the Moraine.

- Niagara Escarpment Plan (NEP): Although the NEP is an example of a geography-specific provincial plan, it is implemented slightly differently than the other provincial plans. The NEP is implemented through a development control system outside of urban areas and is administered by the Niagara Escarpment Commission, an agency of the Government of Ontario. This system requires that the Commission regularly make decisions on site specific applications for development permits in the NEP area based on whether a proposed development is in accordance with Plan policies. While this is done in consultation with municipalities, the Niagara Escarpment development permit takes precedence and must be issued prior to any other municipal approval being granted. The subsequent municipal decisions are required to “not conflict with” the NEP.

- Other provincial plans include the:

- Central Pickering Development Plan, (2012 update) under the Ontario Planning and Development Act, 1994

- The Central Pickering Development Plan was issued to provide planning details for the community of Central Pickering. The Plan took effect on May 3, 2006 and was amended on June 6, 2012.

- Parkway Belt West Plan under the Ontario Planning and Development Act, 1994

- The Parkway Belt West Plan took effect in 1978 to reserve land for infrastructure, separate urban areas, and connecting open spaces in Halton, Peel, York, Hamilton and Toronto.

- Lake Simcoe Protection Plan (2009), under Lake Simcoe Protection Act, 2008

- The Lake Simcoe Protection Plan combines elements of land-use control with regulating certain activities (for example, sewage treatment plant effluent standards) to reduce phosphorus within the Lake Simcoe watershed.

- Source Protection Plans

- Source protection plans are local, watershed-based plans that contain a series of locally developed policies that, as they are implemented, protect existing and future sources of municipal drinking water.

- Source Protection Plans are developed by Source Protection Committees, with support from Conservation Authority and municipal staff.

- Central Pickering Development Plan, (2012 update) under the Ontario Planning and Development Act, 1994

Municipal official plans

Municipal official plans are the primary vehicle for implementing the PPS and provincial plans. Having up-to-date official plans that reflect provincial interests and integrate planning for matters that affect land-use decisions such as sewer and water, transportation, affordable housing, economic development and cultural heritage, provides a foundation for economic readiness and timely decisions on planning applications.

Other regulatory systems connected to land use planning

There are certain uses and kinds of development that have additional and/or separate processes for their approval such as:

- infrastructure development (for example, sewage pipes, wastewater treatment facilities, energy transmission lines, energy generation facilities) - Environmental Assessment Act

- mineral aggregates extraction - Aggregate Resources Act

- landfills - Environmental Protection Act

There are also provincial frameworks regulating operations and activities that may have the potential for negative impacts on the landscape, such as:

- water-taking - Ontario Water Resources Act (permit to take water)

- tree-cutting, and grading of land - Municipal Act, 2001 (tree cutting and site alteration by-laws)

- removing or damaging certain plants or habitat of certain animals - Endangered Species Act

- dumping of toxic waste - Environmental Protection Act

- development and activities in regulated areas including hazardous lands (floodplains, shorelines, valleylands, wetlands etc.) - Conservation Authorities Act (development and interference regulation)

- building of certain structures - Building Code Act (building permit)

Planning decisions and appeals

In recent years there have been a number of changes to Ontario’s land use planning and appeal system. The changes will have an impact on your role as a land use planning decision-maker. For example, the recent changes include:

- establishing the Ontario Land Tribunal as the province-wide appeal body for land use planning appeals, replacing the Ontario Municipal Board

- limiting appeals of certain types of planning matters, such as removing the ability to appeal provincial decisions on new municipal official plans and major official plan updates

You can find more information about the land use planning system, including the Ontario Land Tribunal, in the sections below and in the Citizens’ Guides to Land Use Planning.

The Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT)

People do not always agree on planning decisions made by local planning authorities. Because of this, the Ontario Land Tribunal exists as an independent tribunal to hear appeals and make decisions on a variety of municipal land use planning matters. When people are unable to resolve their differences and/or disputes on decisions made by local planning authorities, they can appeal those decisions to the Ontario Land Tribunal. The failure of a planning authority to make a decision on most planning applications within specified time periods can generally also be appealed to the Ontario Land Tribunal.

The OLT was formerly known as the Ontario Municipal Board before it was renamed the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) in 2018. On June 1, 2021 the LPAT was merged with the Environmental Review Tribunal, Board of Negotiation, Conservation Review Board and the Mining and Lands Tribunal into a new single tribunal called the Ontario Land Tribunal.

When certain matters are appealed to the OLT, the tribunal may take the place of the local planning authority and can make a decision within the authority provided for in the Planning Act.

In making its determination, the Ontario Land Tribunal is required to have regard to the municipality or approval authority’s decision on the matter and any information and material that the municipality or approval authority considered when making its decision.

The Ontario Land Tribunal’s decisions on all matters appealed to it under the Planning Act are final, with the following exceptions:

- when the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing (referred to in this section as the Minister) has declared a matter to adversely affect a provincial interest

- when a request is made to the Ontario Land Tribunal for a review of its decision

- when the court gives permission to appeal the tribunal’s decision to Divisional Court

Any person or public body, subject to meeting certain requirements, can appeal a planning decision with reasons to the Ontario Land Tribunal or, in the case of minor variance, consent or site plan application decisions, to a Local Appeal Body (LAB), if your municipality has established one to hear these appeals.

Participation in the municipal planning process is an important criterion if the public wishes to make an appeal. You may therefore wish to encourage your constituents to participate in planning matters of interest to them. Some planning decisions regarding policies and applications relating to settlement area boundaries or new areas of settlement, employment areas and second residential dwelling units cannot be appealed. Other matters that cannot be appealed include official plans in their entirety, and certain other provincial approvals. You should always ask municipal planning or legal staff to advise you on whether a matter can be appealed. This is another reason why council must consider all relevant local and provincial interests when making decisions.

Local Appeal Bodies

The Planning Act provides municipalities with the authority to establish their own Local Appeal Body (LAB) for appeals regarding applications for minor variances, consents to sever land, and appeals related to site plan matters. Once established, a Local Appeal Body replaces the function of the Ontario Land Tribunal for those matters it has been empowered to hear.

The Local Appeal Body would not have jurisdiction in the case where a consent, minor variance and/or site plan appeal is related to a type of planning matter that is adjudicated by the Ontario Land Tribunal (for example subdivision or official plan).

At the time of writing, only the City of Toronto has established a LAB. On May 3, 2017, the Toronto Local Appeal Body replaced the function of the Ontario Land Tribunal to hear Toronto-based appeals of Committee of Adjustment decisions on minor variance and consent applications.

One window planning service and municipal plan review

While municipalities are primarily responsible for implementing the PPS through official plans, zoning by-laws and local planning decisions, the authority to make land use planning decisions may rest at the provincial or the local level. As a councillor, it is important to understand the authority that your municipality has been delegated or assigned for different land use planning functions.

Where the Minister is responsible for land use planning decisions under the Planning Act, there is a process in place referred to as the “one window planning service.” This streamlined service communicates provincial planning interests and decisions to municipalities using one voice. For example, the Minister approves all upper-tier and single-tier official plans and official plan updates.

Where municipalities or planning boards are responsible for land use planning decisions, there is a process in place referred to as “municipal plan review.” For example, some upper-tier and some single-tier official plan amendments are exempt from the Minister’s approval.

These approval processes were created by the province to:

- act as one-stop portals between decision-makers and applicants for land use matters

- co-ordinate provincial or municipal positions back to an applicant

- maximize the effectiveness of early consultation

- ensure consistent decision-making

- improve planning service delivery and use resources efficiently

The two processes differ in several key ways.

| One window planning service | Municipal plan review |

|---|---|

The Minister provides an integrated provincial decision on applications Partner ministries collaborate to provide advice and technical support to the Minister (guided by an internal memorandum of understanding known as the “One Window Protocol”) Province prepares guidance and support materials and may provide education and training | Municipalities review and make decisions on local planning applications Municipalities are responsible for obtaining technical expertise through external experts, peer review, background studies Municipalities access provincial ministries for technical (rather than policy) support and data sharing |

Regardless of the decision-maker, early consultation is encouraged to ensure an efficient process with the early identification of key planning issues. Decisions shall be consistent with the PPS and conform with or not conflict with provincial plans where applicable. All decision-makers must make responsible, accountable and timely planning decisions.

Aside from the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (referred to as the ministry in the rest of this section) the following provincial ministries are part of the one window planning service that may be consulted to get their input prior to making a decision on any planning application:

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

- Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

- Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines

- Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries

- Ministry of Transportation

- Ministry of Infrastructure

- Ministry of Health

- Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade

Roles of provincial ministries and conservation authorities

Municipal planning also involves obtaining various site-specific permits and/or approvals of a technical nature before a development project can proceed. These permits and approvals typically involve other provincial ministries, and where applicable, a local conservation authority (if one has been established). In most cases, these other ministries and parties should be part of the planning approval review process to identify their interests so they can be built in and/or designed for from the outset. This allows for technical permits further in the development process.

Conservation authorities should work closely with municipalities in using their authority and carrying out their responsibilities related to natural hazard management including flooding and erosion. Conservation authorities may also provide services for their municipalities reviewing proposed plans for matters like natural heritage, spercies at risk and climate change adaptation. Municipally appointed representatives collectively govern a conservation authority in accordance with the Conservation Authorities Act. It is important to understand the roles of the conservation authority or authorities in your municipality and how they work with municipal land use planning process.

The following are the types of work that may require approvals in a regulated area:

- the construction, reconstruction, erection or placing of a building or structure of any kind

- changes that would alter the use, or potential use, of a building or structure

- increasing the size of a building or structure, or increasing the number of dwelling units in the building or structure

- site grading

- the temporary or permanent placing, dumping or removal of any material originating on the site or elsewhere; the straightening, changing, diverting or interfering with the existing channel of a river, creek, stream or watercourse; or changing or interfering with a wetland

- the straightening, changing, diverting or interfering with the existing channel of a river, creek, stream or watercourse,

- the changing or interfering in any way with a wetland

Municipal empowerment

Over the last few years, upper-tier, single-tier and regional municipalities across the province with up-to-date official plans in force have been given additional authority to approve certain planning files (for example, official plans/amendments, subdivisions) in order to give more decision making powers to municipalities and streamline the local land use planning process. This allows the province to focus its resources on broader policy issues involving matters of provincial interest.

Municipal planning tools

This section describes the key planning tools provided by the Planning Act. These tools help municipalities plan and control development and achieve priorities like affordable housing, economic development and growth management. Reviewing your municipality’s planning documents and discussing them with planning staff will give you a better understanding of their application.

The official plan

An official plan describes your municipality’s goals and objectives on how land should be used over the long term and includes specific policies to meet the needs of your municipality. It is prepared with broad input from you and your municipality’s citizens, businesses, community groups, stakeholders and Indigenous communities.

As a councillor, it is your role to make decisions on new official plans, plan updates and privately and municipally proposed amendments to the plan. You must also ensure that those decisions are consistent with the PPS, and conform with or do not conflict with any applicable provincial plan.

It is important for your official plan to be up-to-date. Your official plan addresses issues such as:

- where new housing, industry, offices and shops will go and how the built environment will look and function

- what environmental features and farmland are to be protected

- specific actions to be taken to achieve the provision of affordable housing

- what services, like roads, water mains, sewers, parks and schools, will be needed (and the financial implications of maintaining them through, for example, alignment with your asset management plan)

- when, and in what order, parts of your municipality will grow

- community improvement initiatives

- measures and procedures for informing and obtaining the views of the public on planning matters

When preparing an official plan or amending an existing one, municipalities must inform the public and give people an opportunity to voice their concerns and opinions. For example, council must hold at least one public meeting before the plan is adopted.

In the case of a statutory official plan update, a public open house must be held prior to the public meeting. At the beginning of the review process a special meeting of council must be held to discuss the changes that may be required.

Where the ministry is the approval authority, a copy of the proposed official plan or official plan amendment must be submitted to the ministry at least 90 days prior to the municipality providing notice of a public meeting.

When an official plan has been adopted, the Planning Act requires that notice of adoption be given to any person who asked for it. Once adopted by the municipality, a copy of the official plan is sent for final approval to the appropriate approval authority.

The approval authority is the Minister or the upper-tier municipality that has been assigned the authority to approve lower-tier municipal official plans. It is the responsibility of the approval authority to approve, refuse or modify the plan in whole or in part. Once notice of approval is given, there is a 20-day appeal period provided for in the Planning Act. If no appeal is made, the plan comes into effect once the 20-day period has expired. There is no appeal of a Minister’s decision on a new official plan or official plan update.

However, if part of the plan is appealed or if there is an appeal of the approval authority’s failure to make a decision within the legislated timeframe, the Ontario Land Tribunal would deal with the matters under appeal. After an appeal is made, Council has the authority to suspend the appeal process for 60 days prior to sending the appeal record to the Ontario Land Tribunal to allow time for possible mediation. This allows for a pause in the process to work out disputes and potentially avoid a Ontario Land Tribunal hearing. If the matter proceeds to a hearing, the Tribunal must have regard to the local decision and make its decision based on the facts presented at a hearing.

The Tribunal has authority to make a final decision on the matter and will seek to make the “best” planning decision while making sure their decisions are consistent with the PPS and conform with any applicable provincial plans and municipal official plans. In making its decision, the Tribunal can allow or dismiss the appeal and approve, approve as modified or refuse to approve all or part of the plan or amendment.

As a councillor, you should be aware that council may amend an official plan at any time. For example, the needs of a community evolve and changes to your official plan may be necessary to address new and emerging social, economic and environmental matters that your current plan does not address. These changes may be made through an official plan amendment, which is prepared and approved in the same manner as the plan itself. An amendment can be initiated by the municipality or by the public. It is important to note, however, that applications to amend a new, comprehensive official plan are not permitted for two years after the new official plan comes into effect, unless your council passes a resolution to allow these applications to proceed.

In addition, the official plan amendments of some municipalities are exempt from approval. In these cases, the approval authority has exempted a municipality from requiring its formal approval of the amendment. After a municipality gives notice of its adoption of an official plan amendment, any person, or public body that has made a verbal presentation or a written submission prior to adoption, or the approval authority/Minister, can appeal the adoption to the Ontario Land Tribunal. This appeal must be made within the 20-day appeal period allowed by the Planning Act, and the amendment must be of the type permitted to be appealed by the Planning Act.

If there is no appeal, the amendment comes into effect automatically on the day after the 20-day appeal period expires. You may wish to ask your municipal staff if your municipality’s official plan amendments are exempt from approval by the approval authority.

Your municipality’s official plan provides the overall direction and guidance for planning in your community. Once approved, it means that:

- you and the rest of council and municipal staff must follow the plan

- all public works (for example, new sewers) must conform with the plan

- all by-laws must conform with the plan

If your municipality has an official plan, you are required to review and update the official plan to ensure that it conforms or does not conflict with provincial plans, has regard to matters of provincial interest and is consistent with the PPS. If your municipality creates a new official plan or replaces an existing official plan in its entirety, it will need to be reviewed and updated no later than 10 years after it comes into effect. A five-year review and update cycle continues to apply in situations where an official plan is being updated and not replaced in its entirety.

These measures help to ensure that the plan is kept current and is sensitive to both provincial and municipal circumstances. An up to date official plan supports investment-ready communities with a local vision for how the community will develop.

Zoning by-laws

A zoning by-law controls the use of land. It implements the objectives and policies of the official plan by regulating and controlling specific land uses (and as such, must conform with the plan). A zoning by-law achieves this by stating exactly:

- what land uses may be permitted (for example, residential or commercial)

- where buildings and other structures can be located

- which types of buildings are permitted (for example, detached houses, semi-detached houses, duplexes, apartment buildings, office buildings, etc.) and how they may be used

- lot sizes and dimensions, parking requirements, building heights and densities, and setbacks from a street or lot boundary

As an elected representative, it is your job to make decisions on new zoning by-laws, updates to the zoning by-law, and municipally and privately initiated zoning amendments. You must ensure that those decisions are consistent with the PPS, and conform or do not conflict with any applicable provincial plan. As well, zoning decisions must conform with all applicable official plans.

As with an official plan, your municipality must consult the public when preparing a zoning by-law or replacing an existing zoning by-law. A public meeting must be held before the by-law is passed. Citizens may make their views known either verbally at the public meeting or through written submissions before the by-law is passed. Only a person or public body that does this may appeal all or part of a council’s decision, provided the matter may be appealed. Your municipal staff can advise you on which matters can and cannot be appealed.

Your municipality must also provide 20 days advance notice of the public meeting and provide information about the proposed by-law. After all concerns have been fully considered, council has the authority to pass or refuse to pass the zoning by-law.

Zoning by-law amendments (or rezonings) may be necessary when the existing by-law does not permit a proposed use or development of a property. A rezoning follows the same basic process as passing the zoning by-law itself, including opportunities to appeal to the Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT). An amendment can be initiated by the municipality or by the public.

As with a new, comprehensive official plan, privately-initiated applications to amend a new, comprehensive zoning by-law are not permitted for two years after the new by-law comes into effect, unless your council passes a resolution to allow these applications to proceed.

Any person or public body, provided certain requirements are met, may appeal your council’s decision to the Ontario Land Tribunal within 20 days of the date the notice of the passage of the by-law is given. This can be done by filing the appeal with your municipal clerk. When an appeal is filed, the OLT holds a public hearing and may approve, repeal or amend the by-law. If no appeal is filed within the appeal period, the by-law is considered to have taken effect on the day it was passed by council.

A municipality must update its zoning by-law to conform with its official plan within three years following the adoption of a new official plan, or following an official plan’s five or 10-year update. A municipality is required to hold an open house to give the public an opportunity to review and ask questions about the proposed by-law at least seven days before the public meeting.

Having an up-to-date zoning by-law ensures that the locally developed policies in the official plan are capable of being fully carried out in a timely way. It is an important element of being an investment-ready community.

Minor variances

Generally, if a development proposal does not conform exactly to a zoning by-law, but is desirable and maintains the general intent and purpose of the official plan and the zoning by-law, an application may be made for a minor variance. For example, a property owner with an odd-shaped lot may propose a development that does not meet the zoning by-law’s minimum side yard setbacks. In this case, granting a minor variance eliminates the need for a formal re-zoning application. However, unlike a zoning amendment, it does not change the existing by-law. A minor variance allows for an exception from a specific requirement of the zoning by-law for a specific property, and allows the owner to obtain a building permit.

Minor variances are obtained by applying to the local committee of adjustment, which is appointed by council to hear applications for permission to vary from zoning by-law standards applications. The application process includes a public hearing and a decision by the committee of adjustment. Applications for minor variances are generally assessed against four tests set out in the Planning Act, however municipalities can augment these tests through locally-developed ones as set out in an applicable by-law.

Any person or a public body may appeal a decision of the local committee of adjustment to the Ontario Land Tribunal or a Local Appeal Body if the municipality has chosen to establish one. The Ontario Land Tribunal or Local Appeal Body may dismiss an appeal or make any decision that the committee could have made on the original application.

Plans of subdivision

The Planning Act applies when a property is proposed to be subdivided into separate parcels of land that can be sold separately. One way of subdividing property is through a subdivision plan that is prepared and submitted to the appropriate approval authority. Your municipal staff or planning board officials will advise you on which body approves subdivision plans in your municipality or planning area. Subdivision approval ensures that:

- the land is suitable for its proposed use

- the proposal conforms with the official plan and zoning in your municipality, as well as with provincial legislation and policies

- your municipality is protected from developments that are inappropriate or may put an undue strain on municipal facilities, services or finances

Decisions must be consistent with the PPS and conform any applicable provincial plan.

Subdivision approval is a two-step process. The process begins when a property owner (or an authorized agent) submits a proposed draft plan of subdivision application to the approval authority for review. The approval authority consults with municipal officials and other agencies that are considered to have an interest in the proposed subdivision (such as utility companies). In addition, a public meeting must be held with advance notice. Each application is reviewed in light of existing policies, legislation and regulations.

Comments received from the consulted agencies (including the municipality in which the proposed subdivision lands are located) are also reviewed. The approval authority may either “draft approve” or refuse an application. A draft approval will generally be subject to one or more conditions that must be fulfilled before the subdivision plan is eligible for final approval and registration.

These conditions might include:

- a road widening

- archaeological assessment

- parkland dedication

- signing of a subdivision agreement between the municipality and the developer to secure various obligations that continue beyond final approval

- rezoning requirements

For example, the property owner may be required, as a condition to granting final approval, to enter into a subdivision agreement with your municipality and/or the approval authority to guarantee that services within the subdivision (such as roads and sidewalks) will be constructed to your municipality’s standards.

If council wants to ensure that the applicant follows through with the development, a lapsing provision can be established at the time of draft approval. This is a time frame within which the conditions must be satisfied before the draft approval lapses. If the applicant is unable to fulfill the conditions prior to the lapsing date, the Planning Act permits an extension to the period of draft approval. However, when determining whether a draft approval should be extended, provincial policies and plans must be considered in the review process.

When all draft approval conditions have been met, the subdivision plan receives final approval and can then be registered. The registered plan is a legal document that sets out the precise boundaries of the property, the dimensions of the blocks and building lots and the widths of all streets, walkways, etc., within the property.

Certain persons or public bodies, as identified in the Planning Act, who make their views known by making a verbal presentation or written submission to the approval authority before draft approval is granted may appeal a decision or conditions within 20 days. However, only the applicant and certain persons or public bodies who made a written submission or verbal presentation to the approval authority before it made its decision may appeal conditions of approval after the 20 days have expired. Certain persons or public bodies who made a written submission or oral presentation to the approval authority before it made its decision, or made a written request to be notified of any changed conditions, may appeal any changed condition for which notice is required to be given.

If the subdivision approval authority does not make a decision within the legislated timeframe, the applicant may appeal the lack of decision to the Ontario Land Tribunal.

If a plan of subdivision has been registered for eight years or more and does not meet the growth management objectives of provincial policies or plans, municipalities are encouraged to use their authority under the Planning Act to deem the plan to not be registered and, where appropriate, amend site-specific official plan designations and zoning by-law permissions.

Subdivision approval authorities also have authority to grant approval of condominium proposals pursuant to the Condominium Act, 1998. Although the condominium approval process has not been included in this section, it is similar to the subdivision process with certain modifications.

The consent process

Your municipality can also use the consent process for subdividing property. For example, a property owner who wants to create only one or two new lots may apply for a consent (sometimes referred to as a “land severance”). Consent-granting authority may reside with a municipal council, a committee of adjustment, a land division committee, a planning board or the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Municipal staff will advise you on which body is responsible for land severances in your municipality. Consent decisions must be consistent with the PPS and conform or not conflict with any applicable provincial plan.

When evaluating a consent application, the approval body consults with the municipality in which the subject lands are located, and with agencies that are considered to have an interest in the proposed consent. Many approval bodies will also hold a public meeting with advance notice. Once the approval body has made a decision, it must notify the applicant and any person or public body that has requested notification within 15 days. A 20-day appeal period follows the giving of the notice. If the consent-granting authority does not make a decision within the legislated timeframe, the applicant may appeal the lack of decision to the Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT).

Similar to a subdivision draft approval, a consent approval (known as a provisional consent or consent-in-principle) may have certain conditions attached to it. There may be requirements for a road widening, parkland dedication or a rezoning. If the consent conditions are satisfied within one year, the consent-granting authority issues a certificate of consent. If any of the conditions remain unsatisfied, the provisional approval expires automatically.

Appeals to the OLT – or to the local appeal body, if the municipality has chosen to establish one – must be filed with the consent-granting authority. When a decision is appealed, the OLT or local appeal body holds a hearing and can make any decision that the consent-granting authority could have made on the application.

It is important to note that a consent (or plan of subdivision) is required in order to sell, mortgage, charge or enter into any agreement for a portion of land for 21 years or more. If the two parts are split already (by a road, for example) consent may not be needed. Other instances requiring consents include rights-of-way, easements and changes to existing property boundaries.

If a landowner is proposing to create a number of lots, a plan of subdivision rather than a consent is generally the best approach for the proper and orderly development of the property.

Site plan control

Site plan control gives municipalities detailed control of how a particular property is developed and allows municipalities to regulate the various features on the site. Council can designate areas of a municipality for site plan control, in which case developers must submit plans and drawings for approval before undertaking development. Site plan control can regulate certain external building, site and boulevard design matters (for example, character, scale, appearance, streetscape design). Further, you may require a site plan agreement with a developer. The agreement could set out details such as parking areas, elevations and grades, landscaping, building plans and services. The agreement can be registered on title and must be complied with by the owner and all subsequent owners.

Community improvement

A community improvement plan is another important municipal planning tool in the Planning Act that allows municipalities to prepare community improvement policies. The policies describe plans and programs that encourage redevelopment and/or rehabilitation improvements in a community. Municipalities are required to consult with the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing as part of this process.

Improvements may include:

- industrial area remediation and redevelopment

- streetscape and facade improvements

- refurbishing of core business areas, affordable housing

- heritage conservation of homes or commercial buildings

They may also include land assembly policies to make projects feasible or to create financial incentives that encourage increased housing choices, mixed densities and compact spatial forms in redevelopment and/or rehabilitation areas. Municipalities can make grants or loans within the community improvement plan project areas to help pay for certain costs despite the general municipal prohibition on bonusing. Some municipalities have established Tax Increment Equivalent Financing programs as part of community improvement plans.

Community Planning Permit System (CPPS)

The Community Planning Permit System (CPPS), also known as the Development Permit System, is a discretionary land use planning tool that municipalities can use to make development approval processes more streamlined and efficient, and get housing to market more quickly. Municipalities can use this tool to help support local priorities (for example, community building, developments that support public transit, affordable housing and greenspace protection) and create certainty and transparency for the community, landowners and developers.

The Community Planning Permit System provides a land use approval system that combines the zoning, site plan and minor variance processes into one application and approval process. It gives additional local flexibility in the land use planning system by allowing variations in development standards and discretionary uses. These are subject to criteria and minimum and/or maximum standards that are set out in a community planning permit by-law. A Community Planning Permit System also allows a municipality to establish conditions that can be imposed in making decisions on community planning permit applications, including conditions that require community facilities or services to be made available.

Enabling official plan policies and a community planning permit by-law are required to implement the Community Planning Permit System. Public participation is focused at the front end of the system, which results in increased certainty. After a community planning permit by-law is passed, privately-initiated applications to amend the community planning permit by-law are not permitted for five years, unless the municipality passes a resolution to allow these applications to proceed.

The Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing may require municipalities to use the Community Planning Permit System in specified areas, such as:

- around major transit stations for GO rail, light rail, bus rapid transit and subways

- along main streets or waterfront areas

In these cases, only the Minister can appeal the official plan policies or community planning permit by-law to implement the tool.

Affordable housing

There are a number of tools under the Planning Act, the Municipal Act, 2001 and the Development Charges Act, 1997 that can be used to help create affordable housing.

A range of land use planning and municipal finance tools are available to municipalities to help meet local needs and circumstances.

The Planning Act requires all municipalities to establish official plan policies and amend their zoning by-laws to allow second units in detached, semi-detached, row houses and ancillary structures. The Planning Act restricts appeals of both second unit official plan policies and zoning by-laws to the Ontario Land Tribunal except by the Minister.

The establishment of a second unit is at the discretion of individual homeowners and may take place in existing or new residences. Second units must comply with health, safety and municipal property standards, including, but not limited to, Ontario’s Building Code, the Fire Code and municipal property standards by-laws.

Another land use planning tool that is designed to encourage affordable housing is the garden suite. Garden suites are temporary one-unit, detached residences containing housekeeping facilities that are ancillary to existing houses and that are designed to be portable. To give potential homeowners more certainty given the potential expense of installing a garden suite, the Planning Act provides that garden suites may be temporarily authorized for up to 20 years.

Inclusionary zoning

Inclusionary zoning is a land use planning tool used to address affordable housing needs by requiring that new housing developments need to include affordable housing units. Inclusionary zoning can only be used in protected major transit station areas, areas where the community planning permit system has been mandated or as prescribed by the Minister. A municipality may use the tool to require affordable housing units to be included in residential development of 10 units or more. These units would then need to be maintained as affordable over a specified period of time.

The tool is typically used to create affordable housing for low-and moderate-income households. In Ontario, this means families and individuals in the lowest 60% of the income distribution for the regional market area, as defined in the Provincial Policy Statement, 2020. However, it is critical for municipalities of all sizes to assess whether this is an appropriate tool for achieving their affordable housing goals. Generally, inclusionary zoning tends to work best in locations experiencing rapid population growth and high demand for housing, accompanied by strong economies and housing markets.

The Planning Act and the associated regulations set out the framework for developing an inclusionary zoning program. Each program will differ as it is informed by local affordable housing needs, conditions and priorities. The key components of inclusionary zoning programs include:

- an assessment report on housing in the community

- official plan policies in support of inclusionary zoning

- a by-law or by-laws passed under section 34 of the Planning Act implementing inclusionary zoning official plan policies

- procedures for administration and monitoring, and

- public reporting every two years

Inclusionary zoning is implemented through zoning by-laws passed by lower-tier and single-tier municipal councils. Following the completion of an assessment report to examine potential impacts of inclusionary zoning on the housing market and the financial viability of development, or redevelopment, a lower-tier municipality may adopt official plan policies for inclusionary zoning without any specific or general policies for inclusionary zoning in the upper-tier official plan.

Lower-tier municipalities may wish to discuss and coordinate with the upper-tier municipality on matters relating to administration and monitoring so that affordable housing units created through an inclusionary zoning program are kept affordable over the long-term.

A municipal council may implement inclusionary zoning within a Community Planning Permit System, as set out in Ontario Regulation 173/16 (Community Planning Permits).

Economic development through land use planning

Municipal councils can promote economic development through their land use planning decisions and by implementing planning tools. Your municipality should have an up to date official plan and zoning by-law in order to adhere to required provincial deadlines, and to be investment-ready and able to seek and take advantage of economic opportunities.

The following table summarises some of the Planning Act tools and their benefits:

| Planning Act tool | Description | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Community improvement plans (CIPs) (section 28) | CIPs are used by municipalities as one way of planning and financing development activities that effectively use, reuse and restore lands, buildings and infrastructure. | Municipalities may make grants or loans within designated CIP project areas to help pay for all or part of eligible costs. |

| Brownfields community improvement planning | Provincial participation through the Brownfields Tax Incentive Program (BFTIP) matches municipal brownfield CIP property tax incentives with the provincial education tax portion. | Can provide financial incentive by making clean up and development less expensive. |

| Community planning permit (section 70.2) | Optional land use planning tool that replaces a standard multi-layered development approval process (zoning, site plan and minor variance), with a single process. Previously known as Development Permit System. Inclusionary zoning for affordable housing may be implemented within an area with a community planning permit system established in response to a Minister’s order. | Results in a more streamlined, timely development process that:

|

| Protection of employment lands (sections 22 and 34) | No appeal of a council refusal to re-designate/ rezone lands from employment to other uses. | Allows municipalities to maintain a sufficient supply of serviced and ideally located (near transit, highways, ports, rail, airports) employment lands. |

| Community benefits charges (section 37) | Community benefits charges enable single and lower-tier municipalities to collect funds from new developments or redevelopments to cover the capital costs of community benefits required because of the development. If a municipality passes a community benefits charge by-law, the charge will only apply to development of buildings that are 5 or more storeys and have 10 or more residential units. The maximum charge payable in any instance cannot exceed 4 percent of the value of land being developed. Community benefits charges are a complementary tool to development charges (which allow municipalities to collect funds from developers for any services listed as eligible). Please see Section 9 for more information on development charges. A community benefits charge by-law may be appealed to the Ontario Land Tribunal. Community benefits charges replace the former section 37 density bonusing provisions in the Planning Act, subject to transition rules. | The new tool, which came into effect September 18, 2020, can be used with development charges and parkland dedication to enable growth to pay for growth, so that municipalities can provide important local services that growing communities need.

Community benefits charges increase transparency and accountability providing municipalities with the flexibility to collect funds to help pay for growth related services and infrastructure. CBCs can help make the costs of building housing in Ontario more predictable. |

| Reduction or waiving of application fees (section 69) | A tool that lets council reduce or waive planning application processing fees. | Could reduce the cost of planning approvals. |

| Conveyance of parkland or cash in lieu (sections 42 and 51.1) | Allows a municipality to pass a by-law applicable to all or part of a municipality, which can require the conveyance of land (up to 5 per cent) for park purposes or cash in lieu as a condition of development or redevelopment (s. 42) or as a condition of approval of a plan of subdivision (s. 51.1). | Could act as a financial incentive if the by-law excludes geographic areas where development/ redevelopment is desired or the condition is not imposed on plans of subdivision within that area. |

| Alternative parkland dedication rate for cash-in-lieu dedications (section 42) | Allows a municipality to pass a by-law applicable to all or part of a municipality, which, as a condition of development or redevelopment, can require the conveyance of land for park purposes at an alternative rate of one hectare for every 300 dwelling units. For cash-in-lieu dedications, the alternative rate is one hectare for every 500 dwelling units. Parkland by-laws that make use of the alternative rates may be appealed to the Ontario Land Tribunal. | Can help provide parkland more quickly and address current needs in communities. May be useful in cases of higher density development. |

| Parks plans (section 42) | Prior to passing a by-law and adopting new or updated official plan policies that allow for an alternative rate of land conveyance for park purposes, municipalities must develop a parks plan in consultation with school boards, and, as appropriate, the general public | Better positions municipalities to strategically plan for parks and be prepared for potential opportunities to acquire parkland to meet community needs. Provides opportunities to identify and discuss future surplus sites (including school sites) in the community and plan accordingly. |

| Reduction of cash in lieu of parkland when sustainability criteria met (section 42) | Where sustainability criteria set out in an official plan are met and no land is available for conveyance a municipality may reduce cash in lieu of parkland. | Can reduce cost of development and redevelopment while improving sustainability (could result in energy savings). |

| Reduction or exemption from parking requirements (section 40) | Provides that council may enter into an agreement to reduce or exempt an applicant from parking requirements in exchange for cash payments. | Could reduce cost of development by not having to supply as much parking, which can require additional land or parking facilities. |

A balanced view

Before approving any planning application, you and the rest of council should look closely at all the related environmental, social and financial costs and benefits that may affect your municipality.

Environmental considerations include the effects of development on land, air and water. Social considerations include the local need for housing and job opportunities, as well as the possible demand for additional services such as schools, parks, day cares, nursing homes, group homes and other social support facilities.

From a financial point of view, when developing new official plans or assessing planning applications, council should weigh the benefits of additional tax revenues in light of:

- the capital costs of the hard and soft services that will be required

- the ongoing costs of maintaining those services

- the effects of both the initial and long-term costs on the tax rate and the existing ratepayers

Your municipality may also be undertaking other long-term strategic initiatives such as asset management planning, long term financial planning and planning for affordable housing through a housing and homelessness plan. The objectives and outcomes of these exercises and your land use planning documents should align.

Responsible community planning involves examining both the potential positive and negative impact of a proposed development on your community. The policies your municipality adopts should reflect a balance between supporting the economy, meeting social needs and respecting the environment.

Participants in land use planning

In addition to technical experts, commenting agencies, and the provincial government, there are two other potential important players in the land use planning process: the public and Indigenous communities.

The role of the public

The public plays an essential role in the planning process. Planning decisions made by council directly affect the people living in your community. The planning process is designed to give citizens the opportunity to share views on your community’s planning policies, examine planning proposals, register their concerns and ideas before decisions are made, and appeal decisions.

To ensure that the public and stakeholders are involved and understand the details of the planning process, the Planning Act provides for certain regulations to be made. For example, regulations exist that set out procedures for public involvement in the process, procedures for giving notice of planning applications and other procedures. As these regulations are minimum requirements, your municipality can provide for increased public involvement. Your municipal or planning board staff can explain the regulations related to public involvement in your municipality.

The Planning Act provides flexibility for your municipality to tailor their notice procedures (for example, who receives notice and how it is given) through the use of alternative notice procedures for a broad range of planning matters including official plan amendments, zoning by-laws and amendments, plans of subdivision and land severances. Council can determine whether a departure from provincial notice requirements is appropriate through an official plan public engagement process.

Council can also consider how to meet the Planning Act’s requirements using electronic and virtual channels to engage and solicit feedback from the public on land use planning matters. This may include a mixture of technologies to meet local public needs (for example, webinars, video conferencing, moderated teleconference).

Engaging with Indigenous communities

As neighbours or as community members, Indigenous peoples may have interests in the land use planning decisions of municipalities. There are linkages between land use planning, and Indigenous economies and cultures, their use of traditional lands, and commitment to a healthy environment. Engagement with Indigenous communities on land use planning issues helps with relationship building, information sharing, and achieving common goals related to social and economic development. For more information on municipal engagement with Indigenous communities, see Section 5: municipal organization.

Land use planning for Northern Ontario

If you are a councillor in Northern Ontario, you probably know that some aspects of land use planning are different in your region. Some of the factors that make land use planning in Northern Ontario different:

- all municipalities are single-tier, in comparison to the upper-tier and lower-tier structure of much of Southern Ontario

- in contrast to its vast land base – that covers 90% of the province – about six per cent of the province’s population lives in Northern Ontario. While over half of northerners live in the five biggest cities, many live in smaller, rural communities

- large portions of Northern Ontario have no municipal organization and are referred to as a territory without municipal organization or “unincorporated areas.” While there are a number of local service delivery organizations in territory without municipal organization, including local roads boards, local services boards and planning boards, there are large areas where these services may not be available

- crown land makes up about 87% of the province’s land mass and more than 95% of the land base in Northern Ontario. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry is responsible for land use planning on Crown land, which is generally directed under the Public Lands Act or the Far North Act, 2010. In these cases, it is generally not subject to the Planning Act or the Provincial Policy Statement. Before Crown land is developed, however, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry consults affected councils and takes any official plans and policies that are in effect into account

Responsibility for land use planning in some northern municipalities and in areas without municipal organization is shared by planning boards and the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing.

Planning boards are unique to Northern Ontario and present an opportunity for municipalities to share planning services and coordinate development across municipal boundaries. In territorial districts, the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing can define a planning area that may include two or more municipalities, one or more municipalities and unorganized territory, or only unorganized territory. The Minister can establish a planning board to handle land use planning activities in these areas.

- Members of planning boards representing municipalities are appointed by the municipal councils, and members from areas without municipal organization are appointed by the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing.

- A planning board is authorized to prepare an official plan for a planning area. A planning board also has the power to pass zoning by-laws for areas without municipal organization within a planning area.

- Most planning boards have been delegated a range of other land use planning responsibilities from the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, such as the power to grant consents, approve subdivision applications and administer Minister’s zoning orders.

In areas that are without municipal organization (and that are not Crown land), where planning boards do not exist, the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing continues to make decisions on land use matters such as land division. The Minister has made zoning orders in some areas, which are similar to municipal zoning by-laws, to control land use and development.

Land use planning decisions in our provincial policy-led system are made by informed councillors who consider both technical advice from professional planning staff and the views of the community. Your involvement in community planning will require you to make decisions on issues of public concern that are often controversial. Despite this, your participation in a process that will determine the future of your community may well be one of the most enduring and gratifying contributions you can make as a councillor.

Read more about land use planning.