Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change: Minister’s Annual Report on Drinking Water 2015

The Minister’s Annual Report on Drinking Water 2015 includes an overview of Ontario’s drinking water systems’ performance, our efforts to manage the impacts climate change may have on our water resources and our work to protect the Great Lakes and improve drinking water for First Nations.

Minister’s message

Each year the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change delivers its report on Ontario’s drinking water. As Minister, I’m pleased to share this year’s report, our ninth. It focuses on what is being done, and what we can do together, to protect Ontario’s rivers, lakes and ground water. It also looks more closely at how we’re working to reduce the impacts of climate change on our water.

Climate change is a global reality. It affects the environment in ways that are both direct and complex, including our water. It affects the quality of the water we drink, whether it comes from ground sources or from lakes and rivers. Clean water is vital to peoples’ health and the integrity of our ecosystems. Protecting it is a challenge for everyone around the world, including all of us in Ontario.

While climate change is global, its effects are local too. Many countries and regions now face more droughts due to higher temperatures and less rainfall. Others face floods, as rainfall becomes more frequent and severe. Warmer temperatures and floods can both have a direct, immediate impact on our infrastructure and economy, affecting food production, tourism, transportation and manufacturing.

Climate change can also indirectly impact the sources of our drinking water. Harsher and more frequent storms can wash pollutants and excess nutrients into the water. Excess nutrients and soaring temperatures that warm rivers and lakes can contribute to the growth of potentially harmful algal blooms.

Under the source protection program we are protecting drinking water at its source. I am pleased to inform you that Ontario has approved all 22 source protection plans, and 16 of them are already in effect. These plans are based on science and are locally driven. I congratulate the source protection committees for developing these plans. They will contribute to the health and welfare of Ontarians.

Our ministry is also taking action on climate change by working with Ontario’s national and international partners. We reached a Memorandum of Understanding with Quebec to collaborate on concerted actions to meet the challenge of climate change, and we are one of 11 subnational areas that have agreed on the need for accelerated global action.

We are taking action at home too. After ending coal-fired electricity generation — the largest single greenhouse gas initiative in North America — Ontario met its 2014 greenhouse gas reduction targets.

We are already two-thirds of the way toward our target for 2020, to have these emissions 15 per cent below 1990 levels, and we have established a further target to be 37 per cent below 1990 levels by 2030. To achieve these goals, we have announced a cap and trade program to limit the main sources of greenhouse gas pollution. We have also released an all-of-government Climate Change Strategy and will be launching a detailed action plan in early 2016.

All of this action serves to protect our rivers, streams and lakes from the effects of climate change and safeguard the sources of our drinking water. We are making progress. We are moving forward with our partners and stakeholders — and with you — to work toward a promising future for Ontarians, with clean, safe drinking water. I look forward to working together with you, for our future and our children’s future.

The Honourable Glen Murray

Minister of the Environment and Climate Change

Government of Ontario

What’s in this report?

Ontario’s drinking water continues to be among the best protected in the world. Keeping it protected, and improving the ways we do this, is a challenge not only for the ministry but for all of us, especially as we face the effects of climate change.

Protecting our drinking water and water resources is vital for Ontario and for the government. It’s a shared responsibility too. By working with our partners, at other levels of government, in communities across Ontario, with First Nations organizations and individuals, we can continue to have among the best-protected drinking water in the world.

Protecting the Great Lakes and making sure that they are resilient to climate change is a key priority. They are the world’s largest supply of fresh water, and millions of people rely on their health and sustainability. The first section of this report summarizes the actions we’re taking to help make sure that the Great Lakes stay protected, now and in the future.

Drinking water protection begins at its source. That’s also a shared responsibility, and this report provides updates and news on the work being done by local committees, with multiple stakeholders, to deliver watershed plans to protect drinking water at its sources.

This year’s report includes an update on the ministry’s work with First Nations and the federal government to help improve drinking water on reserves, as well as a summary of the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s report highlighting the state of our drinking water across the province.

I am pleased to note that 99.8 per cent of more than 533,000 test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards in 2014-15.

We’re continuing to develop and adapt our policies and programs to make sure your drinking water is safe and our resources are protected. This report provides updates on emerging issues, such as microplastics, as well as how our blue-green algae 12-point plan is leading to improved sampling and information sharing.

Our ministry is committed to supporting water conservation and innovative water technologies while expanding on our work across ministries, municipalities, conservation authorities, water agencies — and with you — for clean, safe drinking water.

Overview of sections

This report covers a wide range of information on the actions to protect Ontario’s drinking water and its sources while addressing the impacts of climate change.

The Great Lakes and collaboration — What the Province is doing, along with national and international efforts to protect and restore Ontario’s waters.

Source protection — The work being done to protect the sources of drinking water.

Emerging issues — What is happening next in Ontario’s water protection and the science used to address these issues.

First Nations — An update on working with First Nations and the federal government to help improve drinking water on reserves, with a focus on remote communities.

Ontario’s drinking water — An overview of the ministry’s compliance activities that help ensure safe drinking water for the people of Ontario.

The Great Lakes and collaboration

Ontarians rely on the Great Lakes — one of the largest fresh water systems on earth. Ninety-eight per cent of Ontarians live in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin and 95 per cent of our agricultural lands are found in this essential resource. Almost 60 per cent of us get our drinking water from the Great Lakes.

Our population is growing. That puts more demand on the Great Lakes — and makes it all the more important to protect our prime source of fresh water. While the Great Lakes are resilient, climate change is a challenge that impacts all of them. The lakes are also confronted with habitat loss from land development, loss of wetlands and the presence of invasive species and excess nutrients. New challenges need new solutions.

Our role in protecting and restoring the Great Lakes is a key responsibility. Our Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River shoreline is 10,000 kilometres long. This is the longest freshwater coastline in the world and we share responsibility for protecting the water with a number of partners. We work with other provinces and states, First Nation and Métis communities, municipalities and two federal governments.

Protecting the Great Lakes is complex. It requires a great deal of coordination. Our scientists and experts, aboriginal knowledge holders, our officials and our communities are finding ways to meet a wide range of challenges to the lakes — from algal blooms to stormwater to emerging issues such as microplastics. And of course, climate change.

This work requires cooperation, across the Great Lakes and often, in specific areas too. For example, Ontario, Canada, the U.S. and the Great Lakes states are working together to address concerns about the levels of nutrients in Lake Erie.

We’re also working with First Nations and Métis communities, the federal government, municipalities and grassroots organizations who are trying to protect and restore their own areas and shores, for today and for future generations. We share a vision of healthy Great Lakes — water that is drinkable, swimmable and fishable.

Great Lakes Protection Act

In October 2015, Ontario passed the Great Lakes Protection Act which will strengthen the Province’s ability to keep the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River clean, as well as protect and restore the waterways that flow into them.

The act enables Ontario to address significant environmental challenges to the Great Lakes, including climate change, harmful pollutants and algal blooms.

The act strengthens protection of the Great Lakes by allowing the Minister to set environmental targets and provides tools to take action on priority issues in priority geographies. The act also requires the establishment and maintenance of monitoring programs where needed, for the purposes of improving understanding and management of the Basin, as well as regular reporting.

A key principle to guide efforts to achieve Ontario’s Great Lakes goals is recognition of First Nations and Métis communities. Aboriginal communities within the Great Lakes Basin have important connections to the Basin. First Nations maintain a spiritual and cultural relationship with water and the Basin is an historic location where Métis identity emerged in Ontario. The act requires consideration of traditional ecological knowledge in decisions made about the health of the Great Lakes if offered by First Nations or Métis communities, as well as various opportunities for engagement.

The Great Lakes Protection Act enshrines Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy, the Province’s action plan on the Great Lakes, as a living document to be reviewed every six years and reported on in the legislature every three years.

The act also establishes a Great Lakes Guardians’ Council to provide a collaborative forum for discussing and gaining input on issues and priorities relating to the Great Lakes.

More information on protecting great lakes

The Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund

Ontario cooperates at every level to protect our shared source of drinking water and a great deal of work is happening at the grassroots level. The Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund provides support for not-for-profit groups within communities on the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River Basin. Since its launch in 2012, the fund has awarded $4.5 million to 221 community based projects, with grants of up to $25,000 per project.

A new round of funding was launched on August 27, 2015. The fund’s projects and the community groups that undertake them are helping to protect habitat and species, clean up shorelines and restore wetlands to help manage the impacts of harmful runoff from stormwater.

The fund provides grants for projects that contribute to at least one of the following goals:

- Protecting water quality for human and ecological health

- Improving wetlands, beaches and coastal areas

- Protecting habitats and species.

Here are some examples of Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund projects:

- In Lake Erie’s Kettle Creek, local volunteers, post-secondary students and local nature clubs are working with the Drainage Investment Group to help reduce nutrients entering Kettle Creek at two locations. They’re installing flow control structures and riparian buffer strips — vegetation near the water that protects it from adjacent land uses. Buffer strips make the habitat more hospitable for wildlife, lower water temperatures by providing shade and act as a filter for run-off. The group is also helping with water quality testing and a study of the invertebrate organisms that live at the bottom of the creek, whose presence can indicate the water’s health.

- The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Ottawa Valley Chapter engaged high school students to monitor and remove invasive species, clean up a wetland shoreline, and plant native trees and shoreline plants. The work forms part of a new initiative led by the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society called the Youth Wetland Caretaker Network. This community engagement and important field work will help protect wetland habitats and species in the Ottawa Valley.

- The Huron Stewardship Council’s “Trees Beyond Goderich” project helped restore woodlots along the Maitland River that were damaged by tornados and the emerald ash borer in recent years. Working with the County of Huron, the local conservation authorities and volunteer groups such as the Maitland Trail Association and the Lower Maitland Stewardship Group, Trees Beyond Goderich planted more than 800 native trees or shrubs and more than 1,600 seedlings on approximately 20 hectares of land in rural Huron County. Their efforts helped conserve at-risk woodland areas, enhanced riparian areas, improved water quality and wildlife habitat by planting trees along waterways, and increased biodiversity and resilience in woodlands by introducing diverse but rare native tree species.

More information on the Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund

Canada-Ontario agreement on Great Lakes water quality and ecosystem health, 2014

On December 18, 2014, a new Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health was signed, which outlines the federal and provincial governments’ commitments to protect the Great Lakes.

The Great Lakes are Ontario’s primary source of drinking water. Almost 60 per cent of Ontarians get their drinking water directly from the Great Lakes. The Lakewide Management Annex of this 8th Canada-Ontario Agreement includes commitments to further assess and address threats to sources of drinking water in connection with efforts underway under Ontario’s Clean Water Act. These commitments include identifying sensitive areas, mitigating risks to drinking water, and maintaining and developing education and outreach on the protection of drinking water sources.

There is an urgent need for a coordinated and strategic response to reduce nutrients in many of the Great Lakes, and in Lake Erie in particular. Excessive amounts of nutrients, especially phosphorus, entering waters can lead to algal blooms. These blooms can prevent people from enjoying the water and result in harmful effects on our ecosystem.

The Nutrients Annex of this new Canada-Ontario Agreement includes commitments to improve understanding and address issues related to nearshore water quality, aquatic ecosystem health and harmful and nuisance algae. Early efforts are focused on the nearshore and open waters of Lake Erie and its priority tributaries. As part of these early efforts, Ontario is supporting Canada in the development of science-based targets for phosphorus for Lake Erie and its selected tributaries by 2016.

More information on Canada-Ontario Great Lakes Agreement

Collaboration

It’s important for Ontario to work with the federal government, other provinces, states, cities and towns and First Nations and Métis communities to protect the Great Lakes and meet the challenges of climate change.

In addition to the work we do on our own and with the federal government, Ontario has taken a number of steps to work more closely with others:

- In January 2015, new water taking rules took effect to manage large water withdrawals and transfers within the Great Lakes-St Lawrence River basin in ways that are consistent with an agreement we signed with Quebec and eight Great Lakes states. The agreement is called the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement and was signed in 2005. Of note 2015 represents the 10th anniversary of the signing of this agreement.

- In May 2015, Ontario and Quebec announced a Joint Committee on Water Management to improve the way we work together on common environmental issues related to the water we share, including the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River.

- The Lake Friendly Accord signed in June 2015 commits Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta and Minnesota to reduce excess nutrients in rivers and lakes that contribute to algal blooms.

- In June 2015, Ontario signed the Western Basin of Lake Erie Collaborative Agreement with Michigan and Ohio. It commits the parties to work together towards achieving a 40 per cent reduction in the amount of phosphorus entering the Western Basin by 2025.

- In September 2015, the Great Lakes Commission adopted a Joint Action Plan for Lake Erie developed by the Lake Erie Nutrient Targets Working Group, including Ontario. The Joint Action Plan complements the Collaborative Agreement and contains ten commitments intended to help achieve a proposed 40 per cent reduction in the contribution of phosphorus to Lake Erie’s Western and Central basins by 2025.

Ontario is also a member of the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, which recommends priorities for cooperative action on water issues and coordinates the delivery of programs under the council’s strategic vision.

More information on the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment

Showcasing water innovation

Ontario invested $17 million through the Showcasing Water Innovation program to protect water in communities across the province through innovative technologies and practices. The projects produced knowledge and solutions that can be used by other communities both in Ontario and around the world.

Since first reporting in 2013 on the Town of Moosonee’s water meter installation project, the town measured improvements in their water system which can be attributed to the meters.

Six months after the meters were installed, the town was using 20 per cent less water and the cost of chemicals used to treat the water was down 20 per cent. The municipality is also now able to track the amount of water consumed and is better equipped to detect leaks. The meters created water conversation awareness among residents and the volume of wastewater that has to be treated has decreased. These achievements are helping the town effectively manage its water and wastewater systems into the future.

Guelph took steps to improve the efficiency of its water distribution system and fight climate change at the same time. The city utilized a variety of improvements, including technology made in Ontario to monitor and analyze power use and performance of the water system. New components included the implementation of advanced metering, power monitoring at each facility and usage of innovative pressure devices. These improvements along with an energy efficient operational strategy make up the City’s Smart Water Network.

So far these improvements have achieved an energy use savings of up to 7.3 per cent per month. This is equivalent to a reduction of 118 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, and up to 26 per cent per month savings in energy costs. It’s good for the economy and the environment.

In another project, the ministry is funding the Credit Valley Conservation Authority to evaluate low impact development stormwater management and produce guidance to facilitate its implementation. Low impact development mimics natural processes and controls stormwater at its source. This reduces overall stormwater volumes and the likelihood that municipal sewage systems will be overwhelmed. Such overwhelmed systems are an increasingly urgent problem as severe storms occur as a result of climate change.

Some results at study sites show that low impact development management may absorb up to 90 per cent of rainfall and remove up to 99 per cent of suspended solids, as well as 84 per cent of total phosphorus from water that could enter the Great Lakes. Controlling these pollutants at the source prevents them from entering water bodies such as the Great Lakes.

The project has contributed to training more than 4,000 practitioners in new stormwater management technologies. This has had a positive impact on the economy by supporting jobs for local people. A survey of local businesses found anticipated sales of low impact development products and services growing by up to 50 per cent in the next five years.

More information on showcasing water innovation

Lake Simcoe

The ministry’s first Five Year Report on Lake Simcoe was released on October 23, 2015. It marks a milestone in protection of the watershed under the Lake Simcoe Protection Act. After the law was passed in 2008, the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan was established in 2009 as a framework to protect and restore the ecological health of the watershed.

Lake Simcoe is the largest inland lake in southern Ontario aside from the Great Lakes and its watershed is home to more than 435,000 people.

The report summarizes the actions taken to protect the watershed since the launch of the protection plan. Trends are positive. Ontario’s five year report on Lake Simcoe shows the health of the lake is improving.

Long-term spring phosphorus levels, which cause algae in the lake, have improved and some native fish are showing signs of recovery. Pollution contributions from sources such as sewage treatment plants have decreased, even as the population has grown.

Several native cold water fishes and other aquatic life are showing signs of recovery. In the mid-2000s fewer than 20 per cent of Lake Simcoe’s lake trout and whitefish that were caught had reproduced naturally; by the winter of 2014 that rose to 50 per cent.

Lake Simcoe is still under stress from population growth, urban expansion, agriculture, invasive species and climate change. While the report shows a lot of progress, there is still lots of work to be done.

Since 2008-09, the ministry has committed $32.9 million to Lake Simcoe. Through the Lake Simcoe Protection Act and Plan, the ministry will continue to work closely with other ministries, municipalities and stakeholders to move forward.

More information on Lake Simcoe

Source protection

We protect our drinking water in Ontario at many points along the way from its sources to the tap. This is called a multi-barrier approach. The first step in this approach is one of the most important — protecting water at its source.

Approval of all source protection plans

Protecting water starts with the natural sources that supply our drinking water systems. Ontario has the most comprehensive source protection program in Canada, built on watershed-based protection plans. The Clean Water Act ensures communities protect the quality and quantity of their drinking water supplies through prevention — by developing collaborative, watershed-based source protection plans that are locally driven and based on science.

Local source protection committees in 19 source protection areas or regions have developed plans to identify and address existing and potential risks to municipal drinking water in their communities. Committee representatives include municipalities, First Nations, farmers, industry and the general public. Every plan is the result of many years of work and public consultation. All of the plans have been approved:

| Number | Source Protection Plan | Plan Effective Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lakehead | October 1, 2013 |

| 2 | Mattagami | October 1, 2014 |

| 3 | Niagara Peninsula | October 1, 2014 |

| 4 | Catfish Creek | January 1, 2015 |

| 5 | Kettle Creek | January 1, 2015 |

| 6 | Mississippi-Rideau | January 1, 2015 |

| 7 | Quinte Conservation | January 1, 2015 |

| 8 | Trent Conservation Coalition | January 1, 2015 |

| 9 | Ausable Bayfield Maitland Valley | April 1, 2015 |

| 10 | Cataraqui | April 1, 2015 |

| 11 | Raisin-South Nation | April 1, 2015 |

| 12 | Sudbury | April 1, 2015 |

| 13 | North Bay-Mattawa | July 1, 2015 |

| 14 | Sault Ste. Marie Region | July 1, 2015 |

| 15 | South Georgian Bay Lake Simcoe | July 1, 2015 |

| 16 | Essex Region | October 1, 2015 |

| 17 | Central Lake Ontario, Toronto Region and Credit Valley (CTC) | December 31, 2015 |

| 18 | Halton-Hamilton | December 31, 2015 |

| 19 | Thames-Sydenham and Region | December 31, 2015 |

| 20 | Saugeen, Grey Sauble, Northern Bruce Peninsula | July 1, 2016 |

| 21 | Long Point | July 1, 2016 |

| 22 | Grand River | July 1, 2016 |

We are already seeing how these plans are helping us manage activities that pose risks to our sources of municipal drinking water. This includes:

- Putting locally developed risk management plans in place to regulate activities that pose significant risks in vulnerable areas around municipal drinking water intakes and wells with the help of over 200 trained risk management officials and inspectors

- Making changes to provincial and municipal spill response programs to better protect sources of drinking water

- Making changes to agricultural practices around wells

- Reviewing provincial programs to enhance the protection of sources of drinking water

- Requiring the regular inspection of all septic systems in areas where such systems may pose a significant risk to drinking water sources

- Making changes to municipal land use planning decisions to keep incompatible land uses away from drinking water systems

- Placing road signs on provincial and municipal roads to inform the public and early responders of where vulnerable areas are around drinking water supplies, and

- Increasing public awareness of their local sources of drinking water and the importance of protecting them.

The Province has funded the entire planning process, providing more than $250 million to date. This funding supported the development of plans, training, outreach, technical studies and water budgets. Funding has also been provided to landowners and others across Ontario to reduce or remove potential drinking water risks on their properties, in advance of source protection plan approvals. Furthermore, small, rural municipalities are being funded to help offset start-up costs associated with implementing their source protection plans and collaborating with each other in this regard.

Local leadership will continue to play a key role in protecting our drinking water sources.

More information on source protection

Emerging issues

Protecting our water requires constant attention to new risks that can threaten human health and the environment, particularly in a world dealing with climate change. The Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change works hard to address these emerging issues, to identify and understand them and to respond.

Ontario’s research and planning is geared to think ahead, to anticipate and prepare for emerging water issues, to apply new technologies and the best science to protect and restore our vital resource.

Blue-Green algae in Ontario’s lakes

Blue-green algae (the scientific name is cyanobacteria) are primitive microscopic organisms that have been on Earth for 2 billion years. Though not normally visible, they can form a scum-like bloom in warm weather, with calm water and when there are high levels of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. These algal blooms can produce toxins that threaten animals and human health. The number of algal blooms may increase due to climate change.

The ministry responds to blue-green algal blooms when they are reported. As of October 26, 2015, there were 48 confirmed blooms. Municipal residential drinking water systems are required to have filtration, disinfection and other treatment systems that can help remove the algal cells and help neutralize the toxins they contain. At this point, algal toxins have not been detected in any treated drinking water sample at or above Ontario’s drinking water quality standard (1.5 micrograms per litre).

The ministry oversees detailed monitoring of municipal systems where blue-green algae is detected and runs education and outreach programs on this issue; there is a 12-point plan, developed in 2014, to protect the public from blue-green algal blooms. Once a bloom is reported, the water in that location is monitored more frequently. The ministry works with municipalities and local Medical Officers of Health to respond to blooms. The ministry also set up an online site where laboratory test results and information about blue-green algae is shared amongst ministry staff, Ministry of Health and Long Term Care staff, municipal drinking water system owners, public health units and others.

More information on blue-green algae

Microplastics and microbeads

Microplastics are tiny particles of plastic, less than five millimetres in diameter that come from a number of sources — degraded debris, garbage and microbeads. Microbeads are the tiny, non-biodegradable beads found in many consumer products including skin cleansers and washes.

Microplastics are finding their way into Ontario’s waterways. First noticed in the Great Lakes in 2007, when small pellets began washing up on the shores of Lake Huron, scientists are learning more all the time about the threat they pose.

Early studies show that these plastics may impair feeding and nutrition of organisms as small as zooplankton, the building blocks for freshwater and marine life. Some smaller microplastics have shown the ability to move through membranes and enter tissues.

Ontario is currently a leading Canadian jurisdiction undertaking monitoring for microplastics. Scientists at the ministry are doing their own studies, as well as working with other researchers, to get a better understanding of the microplastics in the Great Lakes. The ministry monitors water and sediment quality in the nearshore areas of the Great Lakes. In 2014, it began to assess the occurrence and sources of microplastics in the water and bottom sediment.

Results so far show that the abundance of plastic particles varies widely and depends a lot on location, currents and stormwater runoff. On average, approximately 14 per cent of microplastics were comprised of microbeads while in streams they were present generally in low numbers at less than two per cent.

Microbeads from personal care products are present in the Great Lakes and urban streams and they are only a small portion of the microplastics found there. Fragments from broken down plastic (e.g., containers, bottles) and polystyrene foam particles (e.g., packaging and food containers) are also found in abundance. It’s hard to identify microbeads because they come in different shapes in consumer products. This makes it hard to classify them as experts look for ways to address their presence in the water.

Ontario is also working with stakeholders to ban microbeads in all personal care products sold in the province. Some corporations have committed to voluntarily phasing out microbeads in their products.

In July 2015, Environment Canada announced its intent to add microbeads to its list of toxic substances under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. It is also considering options to manage the manufacturing, importing and sale of personal care products that contain plastic microbeads. Ontario will closely monitor and provide input to the proposed measures under the federal act to ensure they provide an effective ban on personal care products that contain microbeads to protect our lakes, rivers, fish and wildlife. Ontario supports immediate steps to phase out the use of microbeads in consumer products.

More information on microplastics and microbeads

Monitoring quality of Ontario’s water resources

Water monitoring provides valuable information about the health of the Great Lakes, inland lakes such as Lake Simcoe, along with many rivers, streams and groundwater across the province.

Every year, the ministry collects and analyses tens of thousands of water, sediment and aquatic life samples. Information and data from the ministry’s ongoing scientific monitoring helps us to measure the impact of human activities and climate change on our water resources and identify emerging environmental issues.

The ministry has operated a surveillance program on drinking water for 30 years, collecting data on more than 300 contaminants. It’s a rich source of information on contaminants in both source water and drinking water.

The Drinking Water Surveillance Program is recognized internationally as one of the only existing comprehensive data sources on the quality of raw and treated drinking water in North America — critically important for setting standards. The surveillance program, has given us a better understanding of potential threats to our drinking water.

More information on:

First Nations

Ontario continues to work with First Nations to help improve access to safe drinking water. While the federal government is responsible for the provision of safe drinking water on reserves, we’re collaborating with First Nations and the federal government to achieve progress.

The number of First Nation reserves without access to safe drinking water in Ontario remains disproportionately high. Some of the longest-standing drinking water advisories in Canada are found in First Nation communities in Ontario. According to Health Canada, as of May 2015, 34 per cent of on-reserve public drinking water systems in Ontario were subject to drinking water advisories, with 88 per cent of these advisories in effect for more than one year and 67 per cent in effect for five years or more. We continue to collaborate with First Nations and the federal government to achieve progress.

We have learned a lot from previous efforts. Effective collaboration with the federal government and First Nations has been critical to successes and led to improvements. We can build on each other’s strengths — for example, Ontario’s technical expertise.

The Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change and its agencies currently support efforts to improve First Nations drinking water in several ways.

The ministry provides technical support for a number of collaborative projects and conducts engineering design reviews for systems when requested. The Walkerton Clean Water Centre provides training to First Nation operators. First Nations and Métis may participate in source protection planning under Ontario’s Clean Water Act.

Four First Nations participate in the ministry’s voluntary Drinking Water Surveillance Program.

The Ontario Clean Water Agency has also provided operations and maintenance services to some First Nations.

Canada-Ontario First Nations drinking water improvement initiative

Ontario, the federal government and four First Nation communities have worked together to launch innovative, customized and cost-effective ways to deliver clean drinking water. Through this initiative the federal government provides capital funding while the Province and the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation provide technical support and training. All parties collaborate to make key decisions and the result so far is that two long-term boil water advisories have been lifted. The initiative is a potential model for future programs.

Munsee-Delaware and Alderville are two examples of how Ontario is collaborating with the federal government and First Nations through the Canada-Ontario First Nations Drinking Water Improvement Initiative. Projects are small, nimble and effective, bringing solutions to communities that have waited for years for clean drinking water.

In Munsee-Delaware First Nation, a community of 63 homes and seven community buildings near St. Thomas, the existing water supply consists of only individual bored or dug wells and water delivered in bulk. Early estimates of a conventional water treatment system put the cost to improve this at $3.8 million. Instead, thanks to collaboration under the improvement initiative, there’s a better, community-specific solution — a system with two drilled wells and a new treatment plant that will cost $1.7 million. The treatment system has been built and bids have been posted for the water distribution system. Ontario is providing three years of technical support once the project has been commissioned.

Alderville First Nation, with more than 100 homes and buildings, is about 28 kilometres northeast of Cobourg near the south shore of Rice Lake. Its existing water supply also consists of only individual bored or dug wells and bulk water delivery. New treatment equipment is being planned, with filtration, water softening and ultraviolet disinfection. This will cost $500,000, including three years of operation and maintenance compared to previous cost estimates which were nearly double. As in Munsee-Delaware, Ontario is providing technical support for three years after the project is commissioned.

Another project supported by the Showcasing Water Innovation program is at Constance Lake First Nation, a community in Northern Ontario of about 1,470 members of Ojibway and Cree ancestry. Recently, the community switched from a lake source to a groundwater source for its drinking water because of blue-green algae in Constance Lake. However, the surface water treatment system was not equipped to treat elevated iron and manganese in the groundwater.

Constance Lake looked for an innovative solution and came up with a two-step approach. First, it created a water management plan and then it selected an innovative technology to treat the elevated levels of iron and manganese. The water management plan includes actions to ensure long-term sustainability of the community’s water resources, and the innovative technology is a green sand filter that removes iron and manganese without using harsh chemicals and at a lower cost than comparable technologies. The green sand technology is being incorporated into a new water treatment plant funded by the federal government, to be completed in 2015.

Ontario’s drinking water

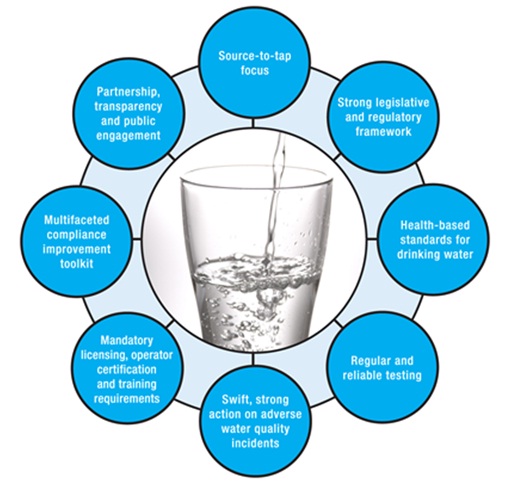

Ontario protects its drinking water through a comprehensive safety net based on the idea that protection starts at the source and continues right to when you turn on your tap. It’s built out of eight parts, to help ensure that Ontario’s drinking water remains among the best protected in the world.

Figure 1: Ontario’s drinking water safety net

Every year Ontario’s Chief Drinking Water Inspector delivers a report on the performance of Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems. The report also looks at the laboratories that perform testing and analysis, the enforcement orders that the ministry issues and convictions against system owners or operators who fail to comply with Ontario’s high standards.

This year we are also providing information from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s report on the Province’s Open Data catalogue. Watch for regular updates to the catalogue in the near future.

Drinking water quality standards

Ontario’s drinking water is among the safest and best protected in the world and our strict, health-based water quality standards are a key part of this protection.

Ontario sets limits for contaminants in drinking water. Most of these are based on Health Canada’s Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines and are reviewed on a regular basis to ensure that they reflect new information when it becomes available.

The Ontario Drinking Water Advisory Council also advises on drinking water quality and testing standards. For more information on the Advisory Council’s work.

My ministry has acted on internationally recognized scientific research and expert advice that recommended strengthening standards for four substances and adopting new standards for four more.

We consulted on the drinking water quality standards as well as the associated testing and reporting requirements through two postings on the Environmental Bill of Rights Registry, one posting on the Regulatory Registry, and by targeted consultations with key stakeholders.

In November 2015, the Province’s Drinking Water Quality Standards (Ontario Regulation 169/03) and Drinking Water Systems (Ontario Regulation 170/03) were amended. We have adopted new standards and strengthened existing ones, and clarified testing and sampling requirements for two substances. The changes will be phased in to allow time for implementation.

The revised and new standards for these substances will improve the quality of drinking water in the province and ensure that Ontario remains a leader in drinking water protection.

Performance results for Ontario’s drinking water

Every year Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems must submit drinking water samples to laboratories that are licensed or eligible to perform drinking water tests. These tests determine whether the samples meet provincial drinking water quality standards.

The performance results as presented in the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report 2014-2015 cover the period from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015.

Key findings of the Ministry’s inspection program 2014-2015

More than 80 per cent of Ontario residents get their drinking water from municipal residential drinking water systems. Every year, ministry staff inspect all municipal residential drinking water systems and laboratories that perform drinking water analysis for Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems to ensure that they meet the Province’s regulatory requirements.

In 2014-2015, these systems demonstrated consistently excellent results and continue to meet Ontario’s strict regulatory requirements.

All 662 municipal residential drinking water systems were inspected:

- 99.8 per cent of more than 533,000 test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards

- 99.4 per cent of municipal residential drinking water systems received an inspection rating greater than 80 per cent

- 67 per cent received an inspection rating of 100 per cent.

Our inspection results also demonstrate that laboratories continue to meet Ontario’s strict regulatory requirements.

Compliance and enforcement activities

When drinking water system owners or operators and licensed laboratory owners do not comply with Ontario laws, ministry inspectors may issue contravention and/or preventive measures orders to resolve and/or prevent non-compliance at a drinking water system.

In 2014-2015:

- One municipal residential drinking water system owner received one preventive measures order.

- Six contravention and two preventative measures orders were issued to eight non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems.

- Two systems serving designated facilities received two contravention orders.

- One contravention order was issued to a non-licensed laboratory facility.

- One operator had its drinking water certificate revoked and one exam applicant received a written reprimand.

There were 17 cases involving convictions at 20 regulated drinking water systems and non-licensed facilities, with fines totalling $161,000.

Operator certification and training

Ontario’s certified drinking water operators are among the best trained in the world. They must go through rigorous training, write examinations and meet mandatory experience and continuing education requirements to obtain and maintain their certification. Drinking water operators must complete 20 to 50 hours of training each year to maintain their certificate.

In 2014-2015, 754 operators received 1,299 operator-in-training (OIT) certificates. Four of these drinking water OIT certificates were issued to four operators employed by First Nations systems.

As of March 31, 2015, Ontario had 6,388 certified drinking water operators, holding 8,916 certificates. Of these, 151 were employed as system operators in First Nations across the province, holding 220 drinking water operator certificates.

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre was established in October 2004 as part of the Province’s response to Justice O’Connor’s recommendations. In 2014-15, the centre continued to provide leading-edge education, hands-on and classroom training, technology demonstrations and information and advice to drinking water system owners, operators and operating authorities across the province. It also serves as a platform for research on cost-effective solutions for small drinking water systems.

As of March 31, 2015, the centre has trained more than 55,700 new and existing professionals. The centre provides high quality operator training programs on water treatment equipment, technology and operating requirements, as well as environmental issues including water conservation. It delivers province-wide training, including on-site training, with a focus on small and remote drinking water systems, including those serving First Nations.

More information on Walkerton Clean Water Centre

Final thoughts

Climate change is a global problem with local impacts, often expressed through water — such as flooding, intense rain, and changing water conditions. Ontario has demonstrated leadership on fighting climate change through a series of measures. We have ended coal-fired power — one of the largest greenhouse gas reduction initiatives in North America. We have improved the province’s commuter rail network. These and other actions have taken us a long way down the road. But there is still much more to do. We have announced a cap and trade program to limit greenhouse gas pollution. We have also released a Climate Change Strategy and will be launching a detailed action plan in early 2016 to deliver on our commitments and transition Ontario to a prosperous low-carbon economy. Our dedicated professionals are working with our partners and stakeholders to make a difference — positive change that will benefit our children, their future, our province and the planet.

Our work on climate change at the ministry will help protect our drinking water.

Our goal is ambitious but achievable. We’re going to keep boosting our efforts to protect the Great Lakes ecosystem, keep our water supply clean and safe and bring our source protection plans into effect. We’re committed to continue to work with our partners — and with you — to protect our drinking water. When you turn on your tap, we want you to be confident that your drinking water in Ontario is among the best in the world.