Aquatic life

Tributary communities

There is an abundance of aquatic life that lives in the tributaries of Lake Simcoe. Their health can be affected by changes to their habitat, such as:

- altered channels

- barriers or removal of overhanging vegetation

- water quality, such as increased chloride or temperature

- invasive species

- flow regimes

The effect of these changes are summarized by the LSRCA using indicators of biotic health in LSRCA (2024).

The small animals without a backbone that live on the bottom of a water body are called benthic invertebrates. Monitoring by the LSRCA continues to show higher indices of the health of tributary benthic invertebrates in headwater streams where there is more shading and a fresh supply of cool groundwater. Communities downstream tend to have lower scores due to changes in habitat caused by natural changes or land uses.

A key indicator of fish tributary communities is the presence of brook trout, a sensitive species that prefers cool, headwater streams. The LSRCA has shown that there are fewer (or no) brook trout in streams when there is more urban area around the monitoring site, with the exception of Kidds Creek in downtown Barrie. This site may support brook trout because of groundwater upwellings that provide fresh, cool water. An example of improving brook trout populations in the watershed occurred in the headwaters of the Pefferlaw River. There, in 2012, a barrier was removed resulting in decreased average summer water temperatures and a measured increase in brook trout abundance (LSRCA 2024).

Lake communities

Macrophytes

Aquatic plants and macroalgae, which are collectively called macrophytes, are a natural and important component of the nearshore area of a lake. They help maintain lake health by filtering contaminants, taking up phosphorus, and providing habitat and shelter for fish.

Currently, there are 27 macrophyte species recorded in the lake, including 3 invasive species (with date they were first reported):

- Eurasian watermilfoil (1984)

- curly-leaf pondweed (1971)

- starry stonewort (2009)

The very recent infestation of water soldier was not included here as it is currently being assessed.

Aquatic macrophytes have been surveyed by the LSRCA approximately every 5 years at over 200 sites around the lake since 2008, with annual monitoring at a subset of 50 sites since 2019. The most recent published survey was performed in 2018 (Ginn et al. 2021) and results were also presented in the Minister’s 10-year report on Lake Simcoe. Another survey was performed in 2024.

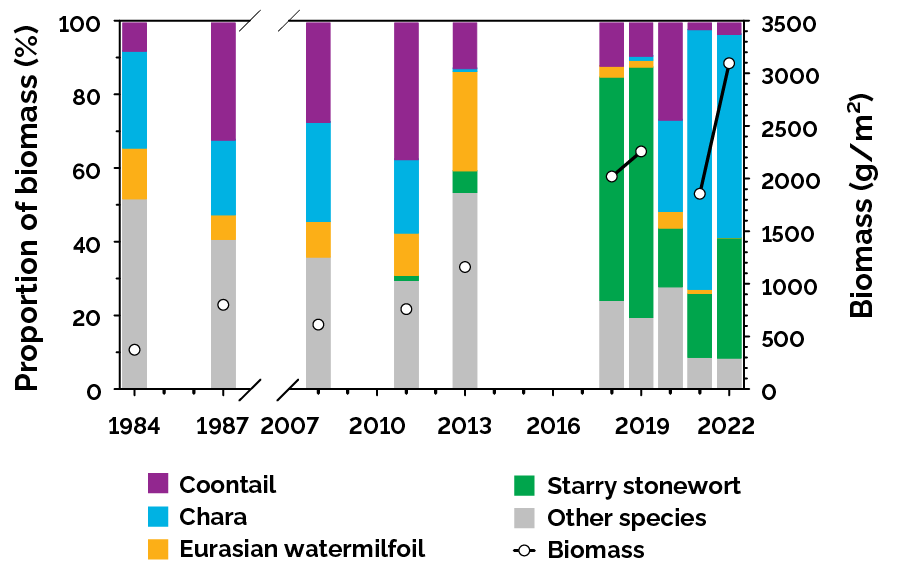

Macrophyte surveys have also been done in Cook’s Bay in many years since the 1980s. These results show that the dominant macrophyte species in Cook’s Bay has changed over the years and that total biomass has increased (Figure 39). Up to 2011, coontail, Chara (also known as muskgrass, a native macroalga) and the invasive Eurasian watermilfoil were the most abundant species. Since 2018, starry stonewort appears to have replaced Eurasian watermilfoil, and, in 2021, Chara became a large component of the community.

In recent years, mean wet weight plant biomass has been > 2,000 g/m2 likely due to both the increase in water clarity, which allows plants to grow at deeper depths, and the dominance of the native Chara species and invasive starry stonewort. As described in the invasive species section, starry stonewort has affected the amount and quality of habitat available for fish and other aquatic species.

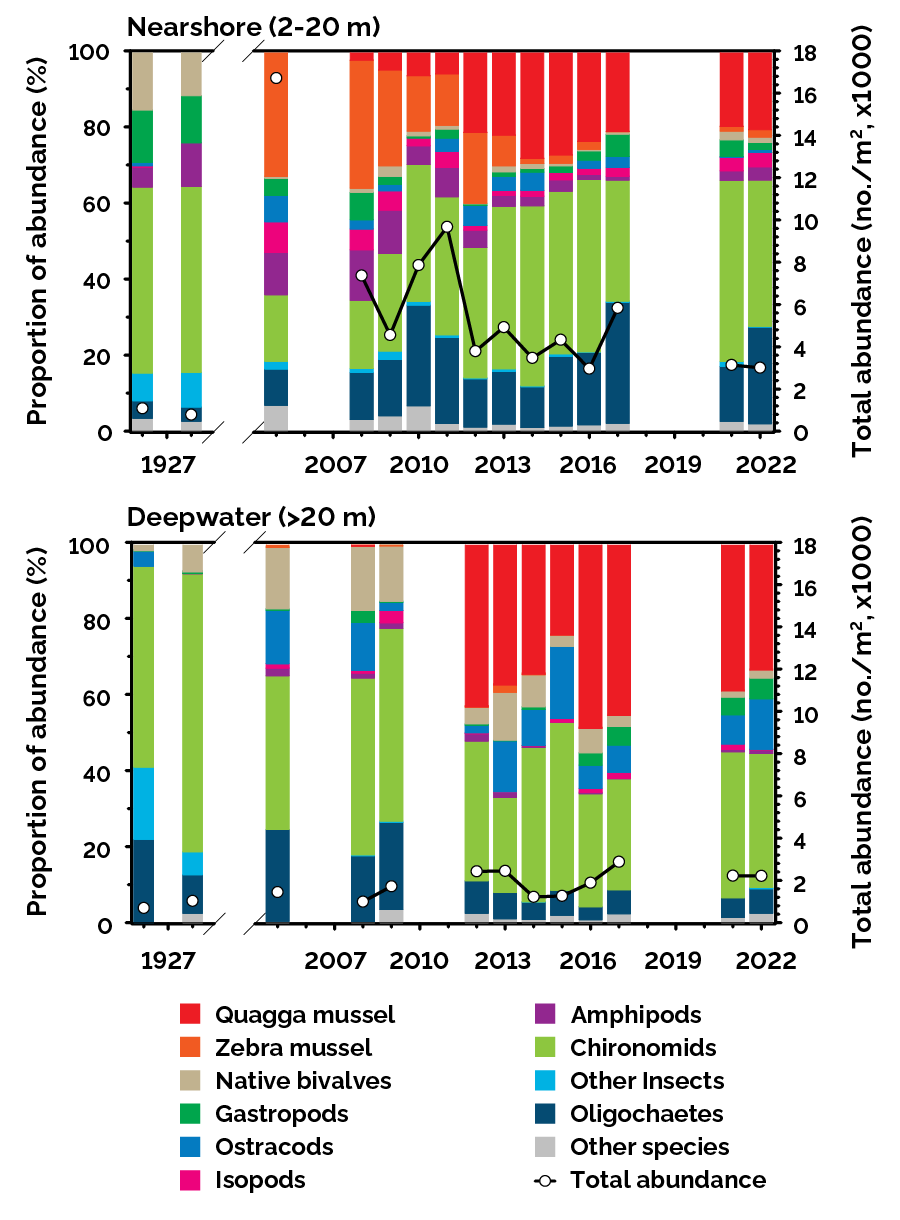

Benthic Invertebrates

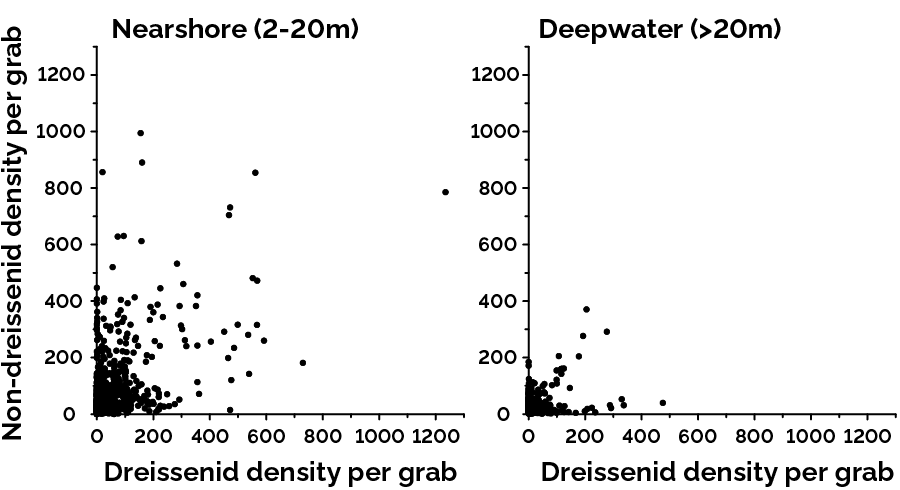

Following the expansion of the quagga mussel in the nearshore and into the deep water of the lake in 2010, the make-up of the invertebrate community living on the bottom of the lake changed (Figure 40). Over the past decade, total abundance and community structure of the lake benthic invertebrate community has been relatively stable with chironomids and quagga mussels dominating, along with oligochaetes in the nearshore and ostracods in the offshore.

In particular, there were higher densities of scavenger species such as oligochaetes, isopods, amphipods and chironomids at quagga mussel sites in the nearshore (p<0.001) (Figure 41). Densities of scavenger species could benefit from the nutrient-rich particles released by the mussels. A benthic invertebrate community dominated by dreissenid mussels and scavengers would likely not provide the same quality of prey for native fish species that feed on the lake bottom.

Phytoplankton and zooplankton of the open water

Microscopic algae and animals that are “free-floating” in the open water of lakes are called phytoplankton and zooplankton, respectively. Phytoplankton use the sun’s energy to grow and feed a lake food web. Zooplankton are an essential link in the food web, as they consume the phytoplankton and in turn are consumed by small fish. Because plankton are sensitive to environmental changes, they are good indicators of ecosystem change. Both types of plankton are monitored in Lake Simcoe by the MECP, along with the concentration of chlorophyll-a, which is a component of all types of phytoplankton and thus can be used as an indicator of the amount of phytoplankton.

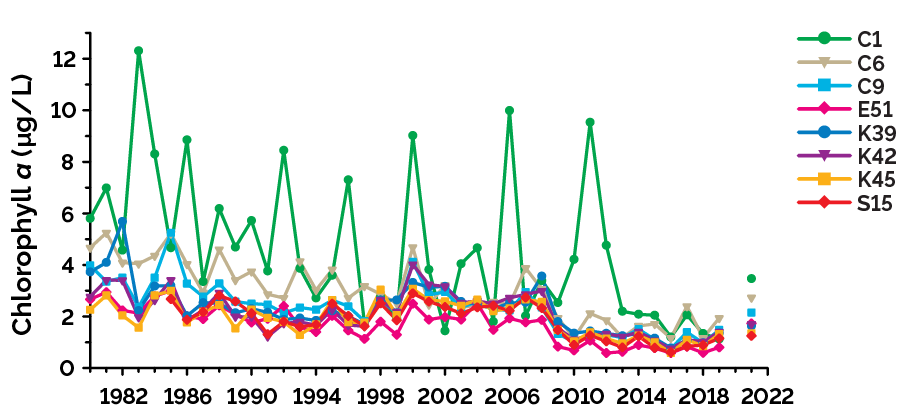

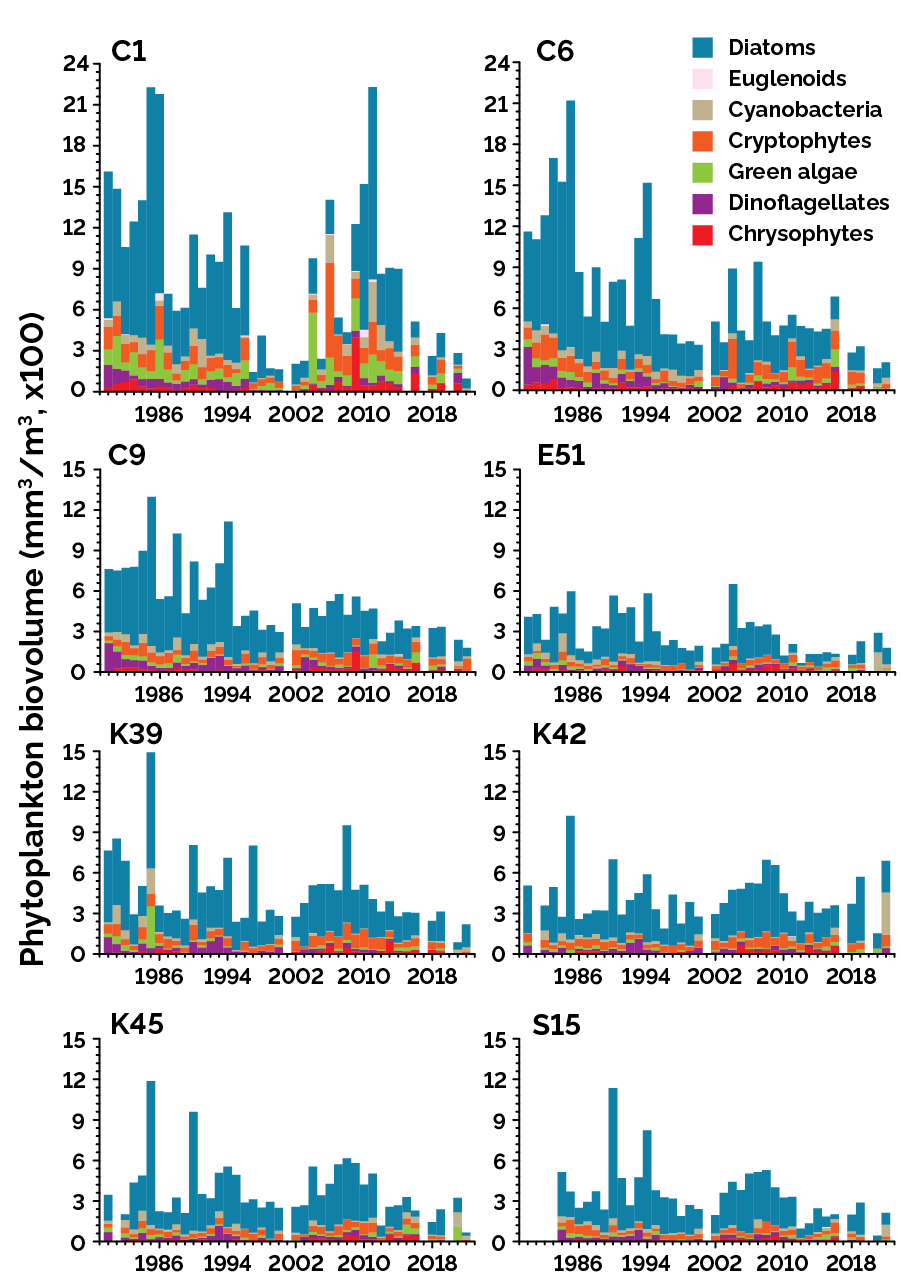

Since 1980, average chlorophyll-a concentration has declined significantly at all lake stations (Figure 42) and phytoplankton biovolume (volume of cells measured by microscopy) declined at all except the 2 deepest stations: K42 in Kempenfelt Bay and K45 in the main basin (Figure 43).

Although numbers vary greatly from year to year, 2 periods of noticeable change in the phytoplankton community occurred. First in the mid-1990s, when only biovolume declined and then rebounded, followed by a period starting in the late 2000s, when both chlorophyll-a and biovolume were lower. The Lake Simcoe phytoplankton community was historically dominated by diatoms but the proportion of this type of phytoplankton has decreased greatly, particularly within the last decade.

Under favourable conditions, phytoplankton can accumulate to form short-lived blooms in lakes. Of the different types of phytoplankton that bloom, such as chrysophytes, diatoms or blue-green algae, only blue-green algae (more correctly called cyanobacteria) have the potential to produce toxins that can be harmful to humans. During the recent data period of this report (2018 to 2022), reports confirmed as blue-green algal blooms in Lake Simcoe were confined to small, localized areas. In 2024, a larger blue-green algal bloom was observed by the MECP in several parts of the lake, but measurements of blue-green algal toxins were very low or undetectable. Triggers for these types of blooms are lake-specific and are not yet clear for Lake Simcoe, particularly as the lake continues to undergo significant alteration from climate change and invasive species.

What to do if an algae bloom is suspected

If you suspect a bloom of blue-green algae, avoid contact and do not use the water for drinking or cooking, even after boiling. It is not possible to tell if blooms contain harmful toxins just by looking at them. Keep people, pets and livestock away from all blooms. Suspected harmful blooms can be reported to the MECP:

- Tel: 1-866-MOE-TIPS (663-8477), 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

- Using the online form at Report pollution online

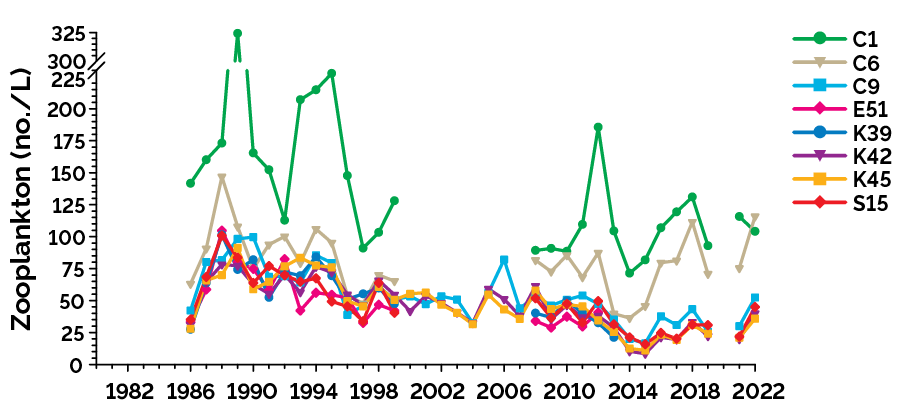

The zooplankton community of Lake Simcoe has experienced significant change since MECP’s zooplankton monitoring began in 1986. Total density of zooplankton decreased in the mid-1990s, following the invasion of the spiny water flea, and further declines in density began around 2013 (Figure 44) at which time abundance of the spiny water flea also declined (Figure 6). The composition of the zooplankton community, in other words, the abundances of the different zooplankton species, has also changed substantially with some species such as the coldwater Daphnia longerimus no longer present (Young et al. 2024).

There are similarities in the timing of the declines in the abundance of phytoplankton and zooplankton. These could be attributed to sequential invasions as well as the effect of climate change on the lake environment (Kelly et al. 2017; Young et al. 2024). Declines of phytoplankton and zooplankton in the mid-1990s were synchronous likely because of the closely timed invasions of the spiny water flea, which preyed on the zooplankton, and zebra mussels, which grazed on the phytoplankton. However, the invasion by quagga mussels in the late 2000s likely affected both plankton groups sequentially by first reducing phytoplankton, thus reducing the primary food source for zooplankton. Additionally, changes to the timing and duration of stratification in the lake as a result of climate change may be affecting both communities.

Importance of diversity to the zooplankton community

Researchers from the Universities of Toronto and Guelph, in collaboration with the MECP, analysed MECP’s zooplankton data from 1986 to 2019 using a portfolio effect technique. They showed that, between 1986 and 1999, there was greater species diversity and seasonal asynchrony in the Lake Simcoe zooplankton community.

With many different zooplankton species, each with different abundances throughout the ice-free season, the total zooplankton abundance was relatively stable providing a constant food source for fishes. However, a loss of zooplankton diversity and an increase in the seasonal synchrony of species abundances during 2008 to 2019 suggested that the structures (for example, portfolio effects) that generate community stability were eroding. These changes coincided with significant changes to the lake due to local and global factors. These results suggest that the zooplankton community of Lake Simcoe is less vulnerable to environmental change when it has a higher species diversity due to both the seasonal and spatial differences between species.

Fish

There are currently 56 freshwater fish species identified as permanent residents of Lake Simcoe (pers. comm. MNR). A fish species was considered ‘permanent’ if caught more than 5 times in the MNR’s standard monitoring programs (Moles 2010). The 4 “new” permanent residents since the 5-year monitoring report are:

- hornyhead chub

- yellow bullhead

- brook silverside

- black bullhead

American eel was also caught more than 5 times; however, it is not a freshwater species and thus is likely not reproducing in Lake Simcoe.

Creel monitoring results

Lake Simcoe has long been a popular fishing destination with the greatest fishing effort of any inland lake in Ontario (Hunt et al. 2022). The harvest of fish species, if not properly managed, however, can contribute stress to the fish community. Lake Simcoe is designated as a provincially significant inland fishery and its fish community is well monitored and researched.

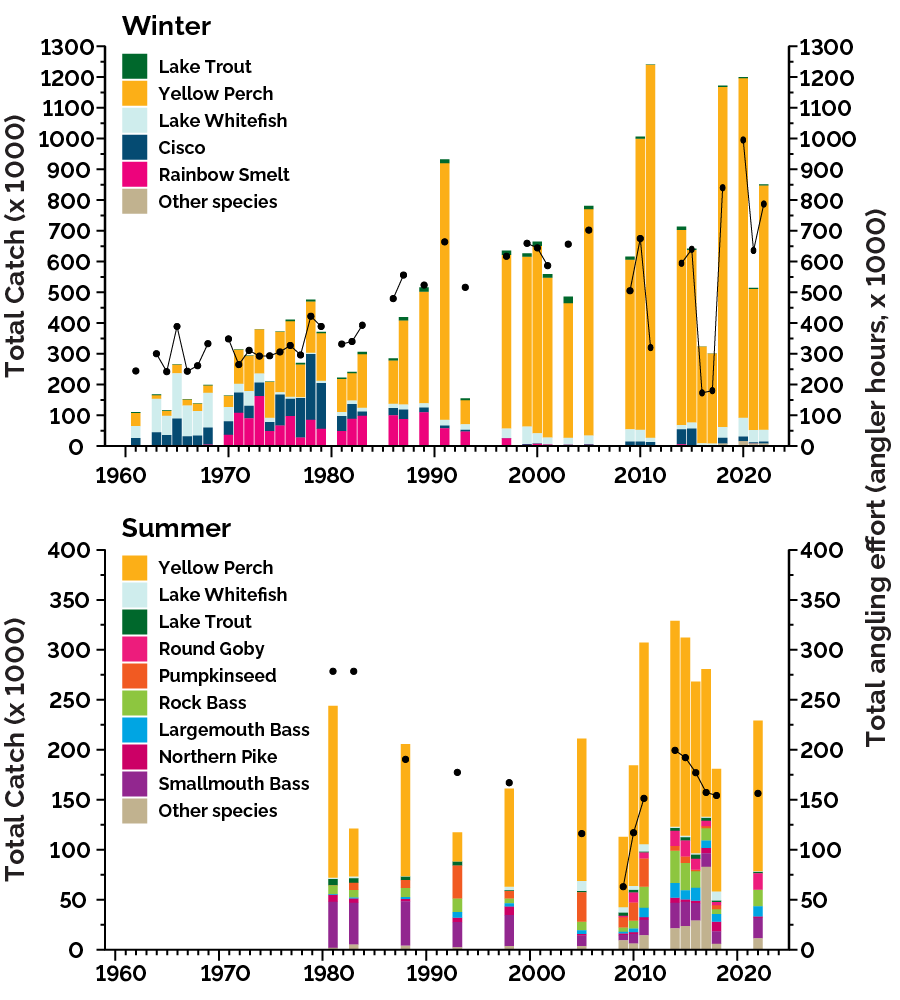

The recreational fishery in Lake Simcoe is dominated by yellow perch. Among fish caught in the 2022 winter and summer seasons, 94% and 66% were yellow perch, respectively. Yellow perch was also the most sought-after fish in both winter and summer. The total number of fish caught in Lake Simcoe reflects the amount of time anglers spent fishing, and both total catch and angling effort have consistently been much higher in the winter than the summer (Figure 45). From 2014 to 2022 (for years with data collected), winter creel surveys estimated an average of 714,542 total fish caught and 605,650 angler hours, while summer surveys averaged 266,652 fish caught and 172,779 angler hours.

Angler surveys and method changes due to decreasing ice

Surveys of anglers, also known as “creels”, have been used to monitor anglers and their fishing habits in Lake Simcoe. These are done every 2 to 5 years to measure the total number of fishing days (total angling effort) and total catch by species. Traditionally, standardized roving creels were performed in boats during the summer (mid-May to September) and on snowmobiles in the winter (end of January to mid-March). However, due to decreasing ice cover duration, and poorer ice conditions and safety in recent years, roving creels have become less reliable during the winter.

Between the winters of 2013 and 2019, both the traditional method of roving creel by snowmobile along with on-land access-point creels by vehicle were used. Since 2020, roving winter creels have been dropped due to ice conditions. Instead, access-point creels and counts of vehicles in parking lots at access points have been used to collect creel data. To analyze these data, a flexible statistical model combining multiple survey types was developed (Tucker et al. 2024). This model provides more robust estimates than previous approaches that relied on a single survey type. Note that 2019 through 2021 summer creel data and 2020 winter creel were not collected.

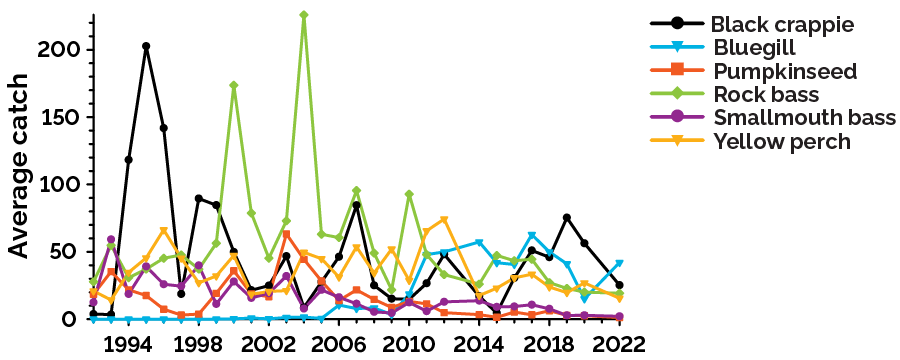

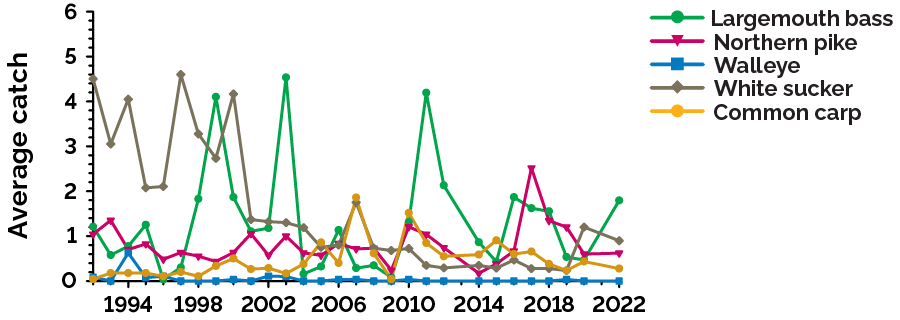

Warmwater fish community

With increased water clarity and water temperatures for greater durations of the year, the nearshore environment of the warmwater fish community has changed significantly in past decades. Despite these environmental changes, the relative abundances of recreationally important fish species, except smallmouth bass, were stable from 1992 to 2022 (Figure 46, 47) (Thorn and Zrini 2022).

The smallmouth bass population has continued to change. Its abundance has continued to decrease over time, while length at age has increased, which has resulted in fewer but larger smallmouth bass in recent years. Yellow perch, northern pike and black crappie remained stable, with no temporal trends in relative abundance or biomass. Bluegill, on the other hand, has expanded in population and distribution. This species first appeared in Lake Simcoe in 2000 and now is the most abundantly caught species in the MNR’s nearshore monitoring program, making up one third of the 2022 total catch.

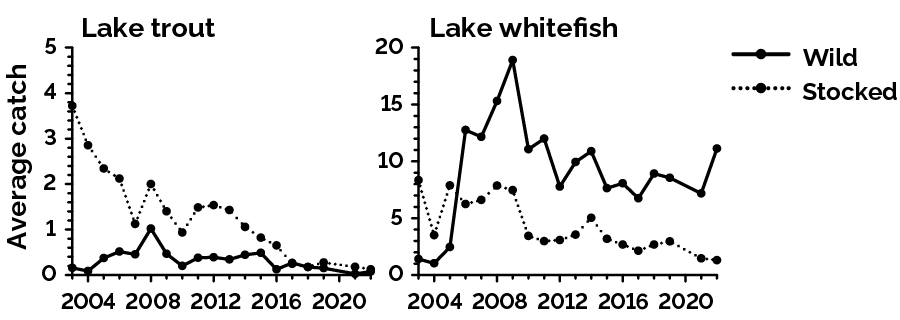

Coldwater fish community

The coldwater fish community of Lake Simcoe is a key indicator in the LSPP, as coldwater fish species are sensitive to low dissolved oxygen levels and changes to the lake caused by the climate. Lake Simcoe’s coldwater fish community was significantly affected by low dissolved oxygen in their deepwater habitat historically. In 1966, large-scale rehablitative stocking efforts began and the fishery for lake trout and whitefish on Lake Simcoe relied almost entirely on stocked fish for several decades until the early 2000s.

Between 2001 and 2009, wild, naturally produced lake trout were documented. Since that time, the number and biomass of both wild and stocked lake trout have declined and are the lowest they have been since the Offshore Benthic Index Netting (OSBIN) monitoring program began in 2003 (left side of Figure 48). In the absence of substantial recruitment, the size of lake trout caught in the OSBIN program has increased concurrent with the ageing of the population.

Wild lake whitefish was abundant and its numbers have remained stable for the past fifteen years (right side of Figure 48). Biomass has increased due to ageing and growth of many wild lake whitefish all born in 2004. Younger wild lake whitefish continued to be caught since the 2004 cohort. On the other hand, the number and biomass of stocked lake whitefish have declined and are the lowest since the early 2000s.

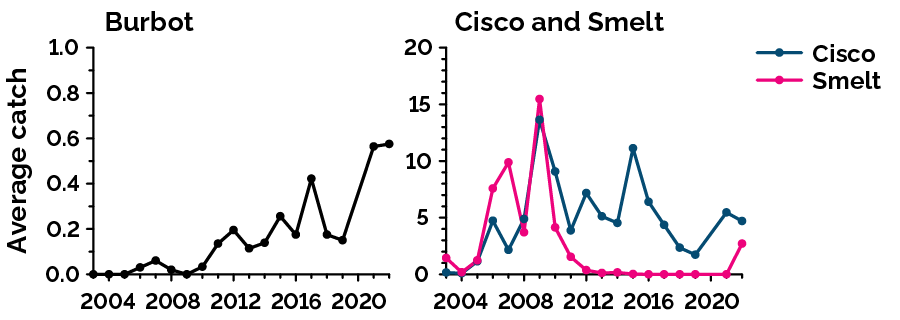

The relative abundance and biomass of burbot, although relatively low, have increased (left side of Figure 49). The relative abundance and biomass of cisco had no temporal trend from 2003 to 2022 (right side of Figure 49). Its biomass peaked in 2009 and then declined. Cisco cohorts regularly appeared on a 4-year basis in the past, while sizeable 2018- and 2019-year classes have recently been caught. Rainbow smelt abundance has been very low; however, there were recent catches in 2022 (right side of Figure 49).

Modernizing monitoring of fish in Lake Simcoe

Starting in 1992 and occurring each August, the MNR’s Nearshore Community Index Netting (NSCIN) program has monitored the littoral fish community of Lake Simcoe using trap nets set in 3 m or shallower waters overnight (Thorn and Zrini 2022). Starting in 2003 and occurring each July, the Offshore Benthic Index Netting (OSBIN) program has monitored the coldwater fish community of Lake Simcoe using benthic nets set in 20 m or deeper waters overnight (Zrini 2024). However, the spatially limited NSCIN and OSBIN methods may not provide reliable estimates of overall abundance and size trends of recreationally important species as these methods individually only sample shallow water or deepwater portions of the lake, respectively.

Broad-scale Monitoring (BsM) is a depth-stratified, standardized fish community monitoring effort conducted by the MNR to track the status and health of Ontario’s inland provincial fisheries. In 2018, a lake wide BsM survey was conducted on Lake Simcoe to investigate spatial bias in the OSBIN and NSCIN methods, and 2 reports were produced that summarized the comparison studies (Thorn and Zrini 2022, Zrini 2024). These reports concluded that the BsM protocol offers a more comprehensive assessment of the fish community by encompassing a broader range of lake depths and habitats than other protocols historically used on Lake Simcoe. Moreover, it holds the advantage of being a widely used and well-studied protocol both within and outside the province.

BsM allows the MNR and partners to leverage the understanding of species biomass and mortality reference points; quantify lake-wide metrics of size and catch per unit effort; and link to zone, regional, and provincial data through the BsM database. In a paired comparison of nets used in the BsM and OSBIN programs, net type did not significantly affect the number of lake whitefish and cisco caught per net when adjusted for differences in the net’s physical dimensions. The ability to understand long-term trends in catch data for these species would not be affected by a transition to BsM. Catches of lake trout and burbot were consistently low in either net type and therefore were insufficient for evaluation.

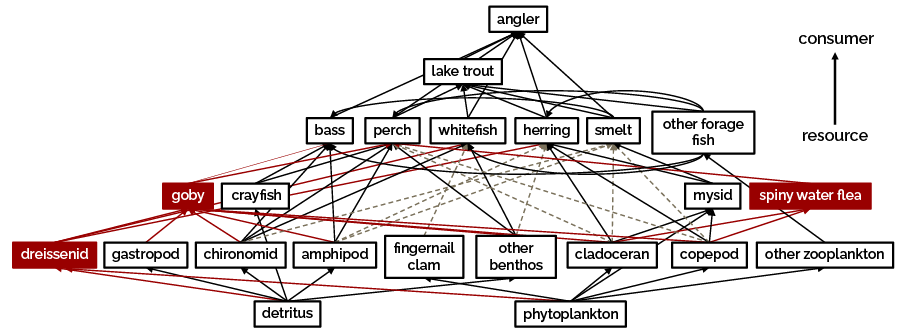

Ecosystem model of the Lake Simcoe food web

An ecosystem model of the Lake Simcoe aquatic food web that was collaboratively developed by the MNR, MECP and the University of Toronto used the wealth of monitoring data available for Lake Simcoe to recreate the food web (Figure 50) of the lake as a computer-based model. Using this model, researchers tested for the effects of fishing, fish stocking, phosphorus reduction and invasive species on coldwater fish populations. A key finding was that lake trout benefitted from phosphorus reductions and improved water quality. However, invasive mussels and spiny water flea decreased the recovery potential of lake trout (Goto et al. 2020).

Internal waves alter coldwater fish distribution

Using nighttime sonar and netting surveys collected in 2015 in Kempenfelt Bay, Flood et al. (2021) examined the vertical position of 2 coldwater fish species, cisco and lake whitefish, to determine if they responded to internal waves to remain in their preferred temperature and oxygen ranges. These fish species typically occupied a narrow vertical band of the lake approximately 5 to 8 m thick located just below the thermocline, which is the depth of greatest temperature change. This depth coincided with the species’ preferred temperature range but was at the lower end of their preferred oxygen range. When the thermocline moved up and down with internal waves, the fishes’ depth moved with it, suggesting that the fishes responded to remain within their preferred thermal habitat. Because oxygen concentrations were sufficient but not ideal at these depths, this study suggests that the fish were responding more to temperature than oxygen concentrations.

The findings in this study have important implications on how and when fish are monitored. Knowing that internal waves can affect the vertical location of cisco and lake whitefish provides information on where to place nets in the lake for monitoring their populations. Also, if internal waves are frequently shifting oxygen and temperature profiles up and down in the lake, then biweekly estimates of end-of-summer deepwater dissolved oxygen may vary depending on when measurements were taken during an internal wave event. Continued measurements have been made with high-frequency data loggers to examine this.

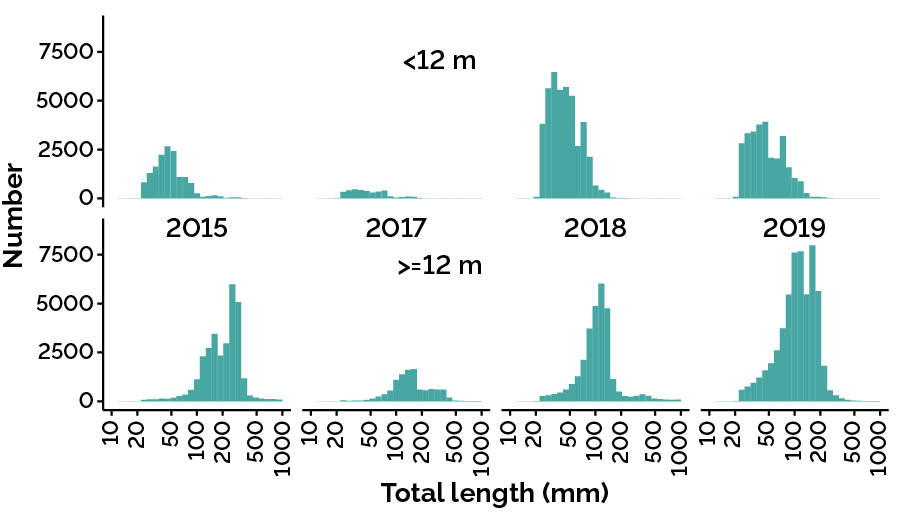

Larval fish surveys

In the spring, fishes in Lake Simcoe hatch from their eggs and can be found near the surface waters of the lake. This young life stage, referred to as larvae, is highly vulnerable and can represent a bottleneck in the population for survival through to older life stages. To better understand why some years produce fewer fish than others, MNR researchers have been sampling these larval fish — the predominant species captured are cisco, lake whitefish and yellow perch — as well as how much zooplankton prey there is available for these young fish to eat at sites across Lake Simcoe (Figure 51). This work is being used to understand how species invasions (for example, by dreissenid mussels), climate change, and other stressors are influencing larval fish diets, growth, and survival and how this affects the numbers of fish available for the recreational fishery.

Results are also being compared to the Great Lakes where fish are experiencing similar stressors. As part of this study, researchers investigated whether the tiny ear stones (called otoliths) from these larval fish can be used to estimate the fish’s age in days, which helps determine when the fish hatched and how fast the larvae are growing. Using larval lake whitefish raised in the hatchery from wild egg collections in Lake Simcoe, it was found that a near daily ring is formed on the otoliths of these fish, allowing researchers to estimate the ages of lake whitefish larvae captured in the wild (Dunlop et al. 2023).

Tracking coldwater fish movement

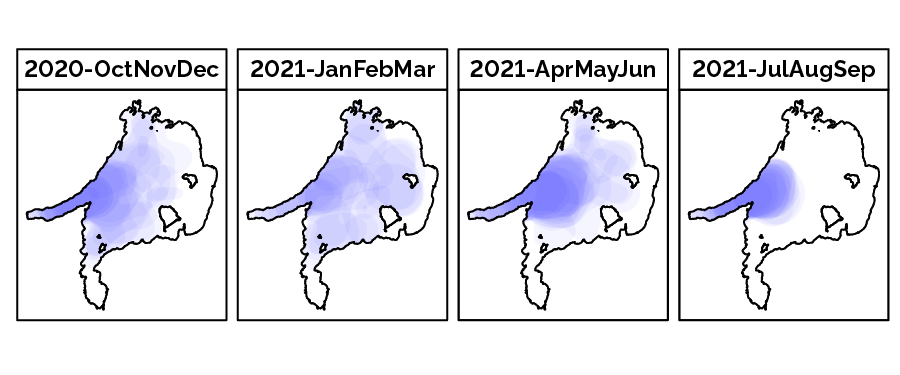

MNR researchers have been using new technology to study the movement and habitat usage of coldwater fishes in Lake Simcoe. Acoustic tags, which “ping” a unique code identifying each fish were inserted into 59 adult lake trout and 63 adult lake whitefish from 2020 to 2022. Some of these tags have additional sensors that measure depth and temperature. An array of 44 underwater listening posts were deployed in the lake to record the signals from these tags as fish swim by.

This project provides data on movement, mortality, spawning behaviour and habitat, as well as differences between stocked and wild fish. A key question being addressed is the role of dissolved oxygen and water temperature in determining the summer habitat of lake trout and lake whitefish. Results so far have shown that lake trout can be found throughout many parts of Lake Simcoe during the winter months, whereas during the summer its distribution is highly concentrated in the deeper, colder water habitat (Figure 52).

Pelagic prey fish dynamics

Several important prey fish in Lake Simcoe are found in the open-water habitats of the lake, making them difficult to assess with traditional monitoring nets that are set on the lakebed (for example, benthic gill nets). These prey fish include cisco, rainbow smelt and emerald shiners, and are an important source of food for predators like lake trout.

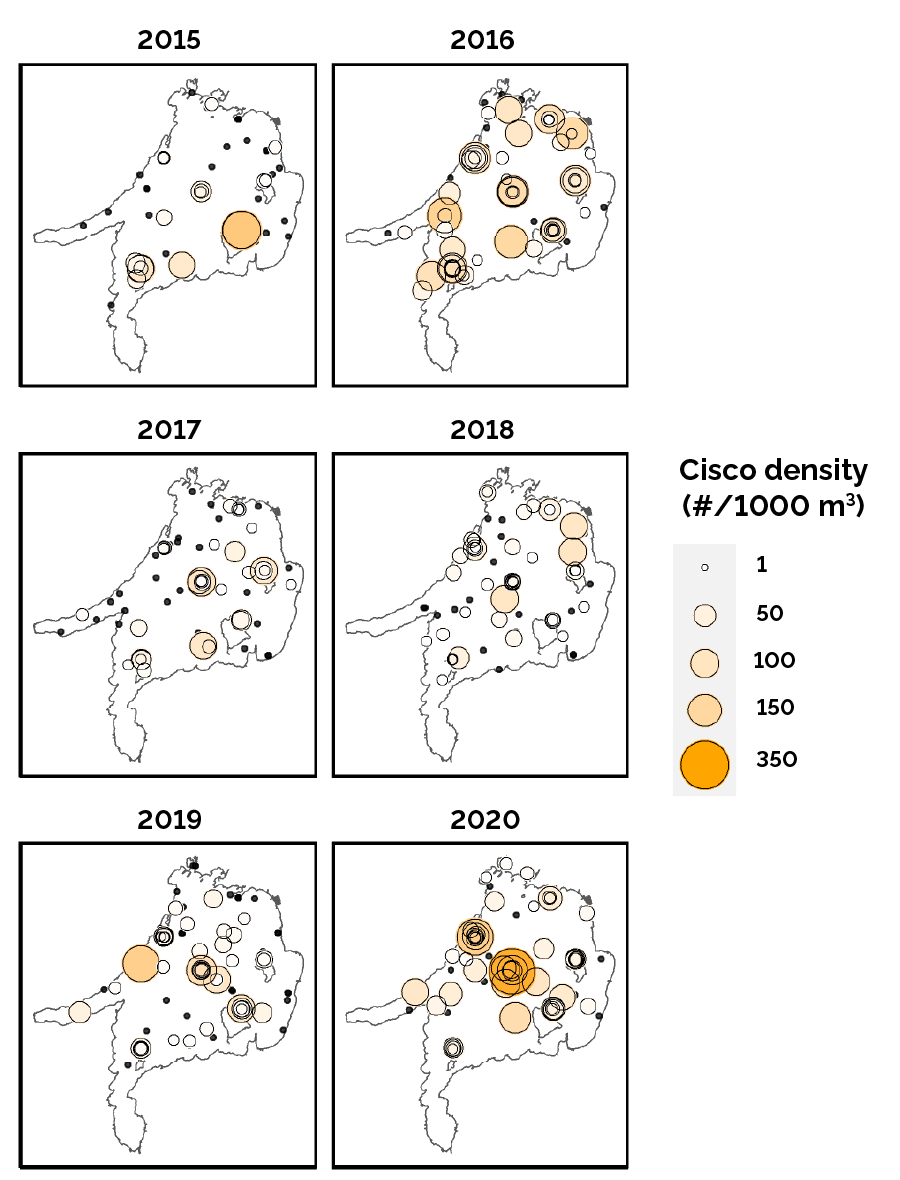

Since 2011, sonar technology called hydroacoustics has been used by the MNR in combination with mid-water netting to assess the status and trends of these prey fish in Lake Simcoe. These surveys detected and tracked multiple strong year classes of cisco, which helped inform the re-opening of a recreational fishery for cisco in 2015. Results have also shown that a strong year class produced in 2012 survived through to older ages and that there have been other prominent year classes produced in subsequent years (for example, 2018).

Estimates of fish size observed with hydroacoustics (shown in Figure 53) allows researchers to track year classes of fish as they grow year-over-year and helps separate different species of fish. These surveys will continue to be used as part of an ecosystem-based approach to understand the responses of the prey fish community to management measures such as changes to lake trout stocking levels.