Invasive species

Many aquatic and terrestrial species within the Lake Simcoe ecosystem were newly introduced to the lake or the watershed, including invasive species. A species is considered invasive when it is both non-native and threatens the environment, economy or society.

Lake Simcoe Invasive Species Watch List

In 2014, the MNR established a Lake Simcoe Invasive Species Watch List to focus on and prioritize prevention efforts for the highest-risk invasive species threatening to be introduced to the Lake Simcoe watershed. Progress has been made on all species identified on the original watch list since the previous monitoring report (Table 3), including:

- regulatory action

- development of provincial strategies and plans

- establishment of collaborative management groups

All of the species on the Lake Simcoe watch list (with exception of the federally-regulated forest insect pests, kudzu and Chronic Wasting Disease) are now regulated under the Invasive Species Act (see management box titled “Ontario’s Invasive Species Act”).

| Common name of species | Progress on species |

|---|---|

| Asian longhorned beetle | Federally regulated (CFIA) |

| Hemlock woolly adelgid | Federally regulated (CFIA) |

| Kudzu | Federally regulated (CFIA) |

| Oak wilt | Federally regulated (CFIA), reporting page |

| Wild boar | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015, Ontario’s Strategy to Address the Threat of Invasive Wild Pigs (2021) [PDF] |

| Chronic Wasting Disease | Reportable disease under the Health of Animals Act (CFIA), Chronic Wasting Disease Prevention and Response Plan |

| Water soldier | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015, Prevention and Response Plan for Water Soldier (Stratiotes aloides) in Ontario (2020) [PDF], Water soldier working group (Trent-Severn Waterway, Bay of Quinte, Lake Simcoe) |

| Parrot feather | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

| Hydrilla | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

| Brazilian elodea | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

| Fanwort | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

| Invasive carps | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015; Regulated federally under the AISR (DFO); Ontario member of the Invasive Carp Regional Coordinating Committee |

| Northern snakehead | All snakeheads regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 and federally regulated under the AISR (DFO) |

| Stone moroko | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

| Yabby crayfish | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

| Wels catfish | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

| Tench | Regulated under the Invasive Species Act, 2015 |

Of the species included on the 2014 Lake Simcoe Invasive Species Watch List, only 2 species are currently found within the Lake Simcoe watershed: oak wilt and water soldier.

Oak wilt

Oak wilt was detected in Springwater Township in July 2023. This invasive fungal disease (Bretziella fagacearum) is transmitted among oak and chestnut trees by native beetles. Vulnerability for the fungus differs among oak species — some die within the year, while in others mortality occurs within 2 to 6 weeks following infection. In response to the detection of oak wilt, the MNR installed several insect flight traps near the infected tree. The aim was to identify potential insect vectors present in the area. MNR staff in the Forest Health Research Program have also been working to adapt management strategies used for oak wilt in the United States, where it is common. The research program is also working to improve detection of the fungus. In 2024, Simcoe County and Springwater Township partnered with the MNR and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to improve the detection of oak wilt fungus on beetles collected from insect flight traps. There are currently 15 partners across southern Ontario.

Water soldier

Water soldier is an invasive aquatic plant native to Europe that is regulated under Ontario’s Invasive Species Act. It was detected in the Black River, a tributary of Lake Simcoe, in October 2015. Since then, collaborative monitoring and management efforts have included:

- development and implementation of a rapid response plan to contain and control spread

- manual removal

- herbicide applications

- over 700 staff hours of field surveys

No water soldier plants have been observed in the Black River since 2017. Furthermore, annual eDNA monitoring by the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters and the MNR has not detected the presence of water soldier in the Black River.

In 2024, water soldier was found on the southern side of Lake Simcoe in Cook's Bay. This new infestation is unlikely to be related to the previously detected and successfully controlled water soldier population in the Black River. Upon receiving the initial report of water soldier in Lake Simcoe, the Ontario Water Soldier Working Group, including members from provincial ministries, Indigenous organizations, municipalities, conservation authorities, universities, federal agencies and other environmental organizations quickly mobilized to survey the area and explore management and treatment options. Currently, work is ongoing to assess and manage the infestation.

Ontario’s Invasive Species Act

In 2015, Ontario passed the Invasive Species Act. The act is focused on preventing the introduction and spread of invasive species (both terrestrial and aquatic) that threaten Ontario’s natural environment, including the Lake Simcoe watershed. It provides legislative tools to prohibit and restrict high-risk invasive species and carriers that help invasive species spread. The legislation and accompanying regulations came into force in 2016. Since then, 42 species have been regulated as well as 4 groups of species and 2 carriers (Ontario Regulation 354/16): watercraft and watercraft equipment.

Carriers (watercraft and watercraft equipment): In 2022, the province regulated watercraft and watercraft equipment as carriers of spread for aquatic invasive species. Watercraft (such as motorboats, rowboats, canoes, punts, sailboats, rafts or other related equipment) may only be transported overland and placed into a body of water if:

- drain plugs and other devices used to control drainage of water are opened or removed at the boat launch and before transporting a boat overland

- the boat is cleaned of any invasive species

These rules help prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species across Ontario and protect Ontario’s biodiversity.

Lake Simcoe Aquatic Invasive Species Guide

Ontario has worked for over 30 years with the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters on invasive species awareness through Ontario’s Invading Species Awareness Program. This program develops and implements innovative education and awareness programs, addresses key pathways contributing to introductions and/or spread, and facilitates monitoring and early detection initiatives for invasive species. These objectives are met through a variety of initiatives and programs. A key component of this work for Lake Simcoe includes development and promotion of the Lake Simcoe Aquatic Invasive Species Guide. This guide lists the aquatic invasive animals, plants and invertebrates in Lake Simcoe that are established and present, as well as how to identify them. New species added to the list that were not included in the 5-year monitoring report’s list of aquatic invaders are banded mystery snail and Chinese mystery snail. The guide also describes 14 “threat” species that have the potential to be easily introduced to the watershed and that would be especially harmful.

Established aquatic invaders

The abundances of key established aquatic invaders are monitored in Lake Simcoe and many of them continue to have an effect on the ecosystem.

The spiny water flea

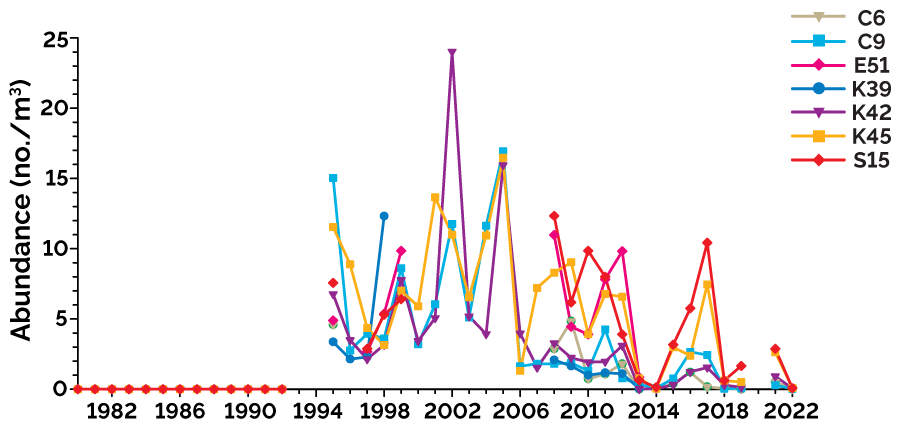

The spiny water flea (Bythotrephes cederstroemii) is a predator measuring around 1 cm in length that established itself in Lake Simcoe around 1994. It is a type of zooplankton, which are small crustaceans that live in the open water of lakes.

The spiny water flea significantly reduces abundances of its prey, the smaller zooplankton, and has had substantial effects on native zooplankton communities (Barbiero and Tuchman 2004), including those in Lake Simcoe where abundances of some native zooplankton species, such as Daphnia retrocurva, were rarely observed for a decade after its invasion (Young et al. 2024). Species such as this Daphnia are an essential link in the lake food web, as they consume primary producers (the phytoplankton) and serve as food for small fish.

In Lake Simcoe, the reduction of zooplankton by the spiny water flea likely led to less food for small fish, including young lake trout, suggesting that this invader contributed to slowing the recovery of coldwater fish species (Goto et al. 2020).

Since its establishment, the spiny water flea has declined significantly at all Lake Simcoe stations (except E51, where sampling was less frequent) (Figure 6). It appeared to decline in the late 2000s, which coincided with the recovery of vulnerable zooplankton species (Young et al. 2024). The decline of the spiny water flea could be driven by other changes in the ecosystem:

- increases in abundance of its key predator (cisco)

- increases in water temperature

- indirect effects from other invaders

Invasive mussels

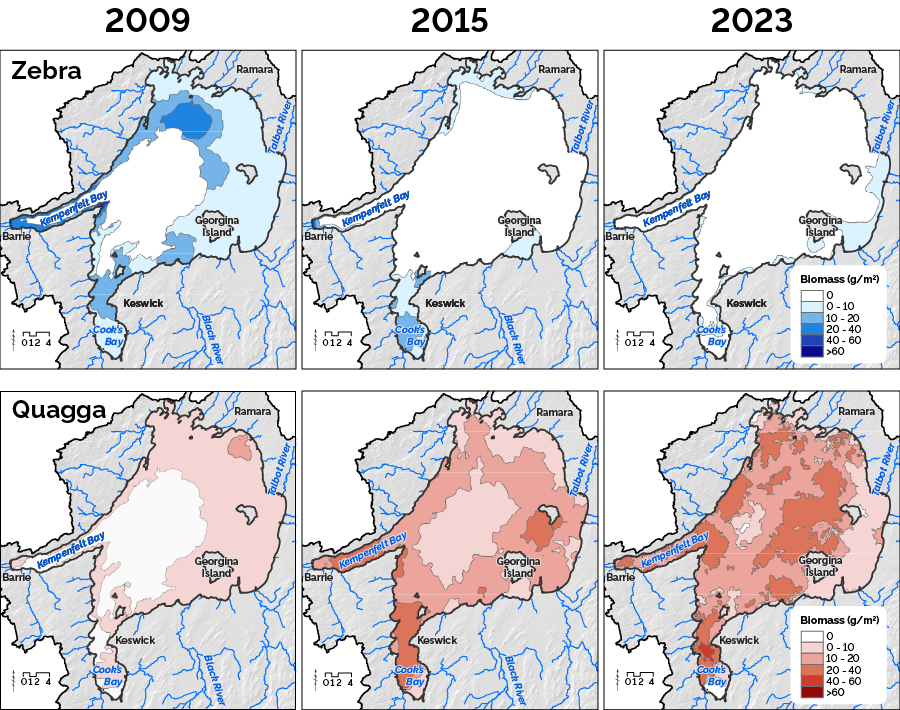

There has been a shift in the species of invasive mussels in Lake Simcoe over the past 15 years that was detected by the LSRCA’s lake wide mussel assessment monitoring. The zebra mussel (Dreissenia polymorpha), which had high densities in the lake from around 1996 to 2010, has substantially declined and is now isolated to small shoreline areas such as along the eastern shoreline and Cook’s Bay (top of Figure 7). In its place, the quagga mussel (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis) has become dominant.

The quagga mussel was first detected in Lake Simcoe in 2004 by the MNR, surpassed zebra mussel densities sometime between 2009 and 2015, and as of 2023 made up 99.2% of the dreissenid mussel population, covering almost the entire bottom of the lake (bottom of Figure 7). Unlike zebra mussels, the quagga mussel does not need hard substrate for habitat, so the quagga mussel population was able to expand its range to the soft substrate in the deeper parts of the lake.

Mussels filter the lake water and consume phytoplankton, which are free-floating algae and are the primary producers in a lake. There are now about 1.2 trillion quagga mussels in Lake Simcoe that could theoretically filter the volume of the entire lake in 3.6 days (pers. comm. LSRCA). Thus, quagga mussels have the capacity to significantly alter the phytoplankton community of Lake Simcoe, presumably more than the shift noted following zebra mussel invasion in the mid-1990s (Winter et al. 2011, Kelly et al. 2017). Food web impacts in Lake Simcoe are also expected to be larger relative to zebra mussels since the quagga mussel can reproduce and feed at much cooler temperatures (4°C) than the zebra mussel (12 to 20°C) (Karatayev and Burlkova 2022a,b), allowing it to feed and grow throughout the year.

Further significant effects on the Lake Simcoe ecosystem could follow a similar trajectory to that seen in the Great Lakes, where quagga mussels similarly replaced zebra mussels as the dominant invasive mussel. Following quagga mussel establishment in Lake Michigan, substantial declines were observed up the food chain, from phytoplankton to zooplankton and possibly to offshore planktivorous fishes (Pothoven and Fahnenstiel 2015). Also in Lake Michigan, a significant reduction in the late winter and spring phytoplankton abundances was observed following quagga mussel establishment (Vanderploeg et al. 2010).

Stable isotope research on food web changes

Stable isotopes can be used to help understand changes to the pathways of energy flow in a lake’s food web. Using carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes, Rennie et al. (2013) illustrated changes to the nearshore Lake Simcoe food web following zebra mussel establishment; meanwhile, similar changes were not observed, or occurred to a far lesser degree, in the offshore fish and invertebrates. Further changes in energy flow in Lake Simcoe have likely occurred following the establishment of the quagga mussel, which now also covers the offshore lake bottom. To investigate, the LSRCA with support from the province will be doing a similar stable isotope food web study in 2025 to 2026.

Round goby

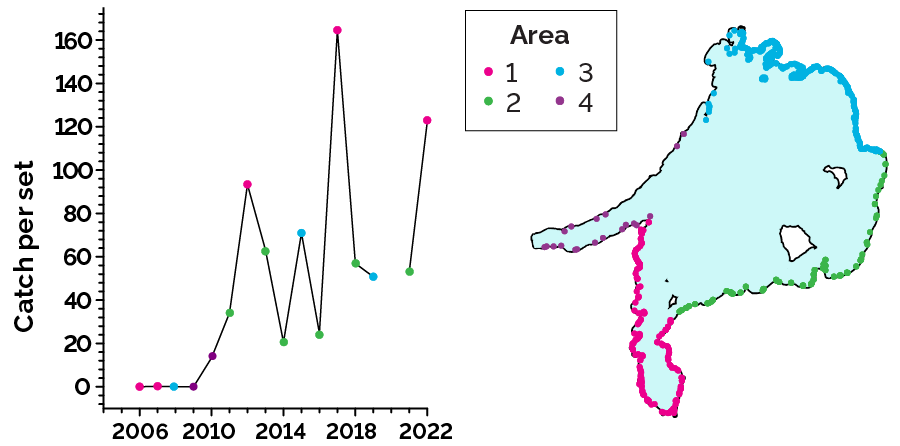

The first round goby (Neogobius melanostomus) spotted in the Lake Simcoe watershed was in the Pefferlaw River in 2004 and, by 2011, this invasive bottom fish had spread throughout the lake at relatively high abundances (Young and Jarjanazi 2015). Since 2012, round goby abundance has not changed as observed from MNR’s small fish sampling program around the lake (Figure 8). Round goby has been captured in the lake by anglers every summer since 2009 (Finnigan et al. 2018).

Round goby has altered the Lake Simcoe food web and likely has had both negative and positive effects (Finigan et al. 2018). It can negatively affect other fish by competing for food and by preying on them or their eggs. It can also transfer contaminants through the food web. On the other hand, the prey of round goby includes invasive mussels and the spiny water flea, thus potentially helping to control invaders in the lake (Johnson et al. 2005). Round goby is also prey to both warmwater (black crappie, rock bass, smallmouth bass, yellow perch and round goby), and coldwater (lake whitefish and, beginning around 2016, lake trout) fish species, possibly providing winter forage (Finigan et al. 2018).

Invasive macroalga

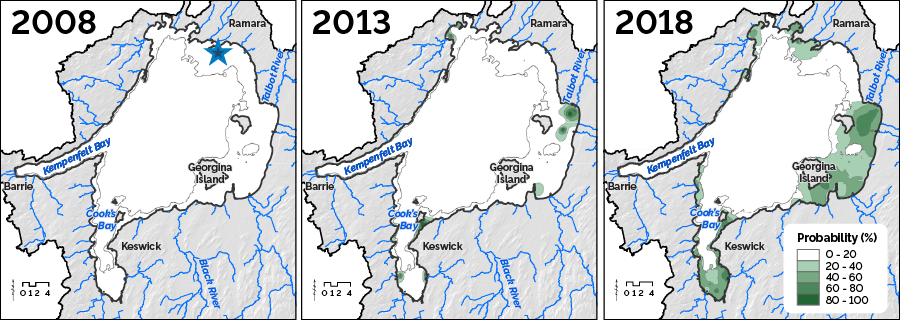

Starry stonewort (Nitellopsis obtusa) was first detected in 2009 by the LSRCA during routine benthic sampling on the northeast shore near Ramara (Ginn et al. 2021). By 2011, it was recorded in Cook’s Bay and in 2018, it was the dominant macrophyte in Lake Simcoe (67.6% of the total biomass) (Figure 9).

While starry stonewort looks like a plant, it is in fact a macroalga. This means it does not have roots and it takes up nutrients from the water rather than the sediments, similar to seaweed in marine coastal systems. By nature of its growth, it forms thick, dense mats underwater that prevent growth of other aquatic vegetation. Areas with starry stonewort are also unusable by small fish, as the mats are too dense to penetrate, pushing these fish offshore where they are more vulnerable to predators.

Annual sampling of starry stonewort in Cook’s Bay by the LSRCA suggests that it reached a peak in Lake Simcoe in 2019 and then declined (Table 4). A decline in starry stonewort also occurred at the same time in lakes in Central Ontario and the United States Midwest where it is also widespread (Harrow-Lyle and Kirkwood 2022, Alix et al. 2017).

| Year | Biomass (g/m2) |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 0.00 |

| 2011 | 10.41 |

| 2013 | 68.38 |

| 2018 | 1003.25 |

| 2019 | 1535.40 |

| 2021 | 321.44 |

| 2022 | 1008.54 |

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Starry stonewort biomass data for Table 4 were collected by the LSRCA using grab samples at 25 sites and standardized to mean wet weight per square metre.