Climate change

Climate projections by the LSRCA have suggested that further increases in air temperature and changes in precipitation events are expected to occur on the Lake Simcoe watershed. By the end of this century, annual mean temperature is expected to increase up to 5.5°C with the largest temperature increases occurring in winter (LSRCA 2024).

Meteorological trends

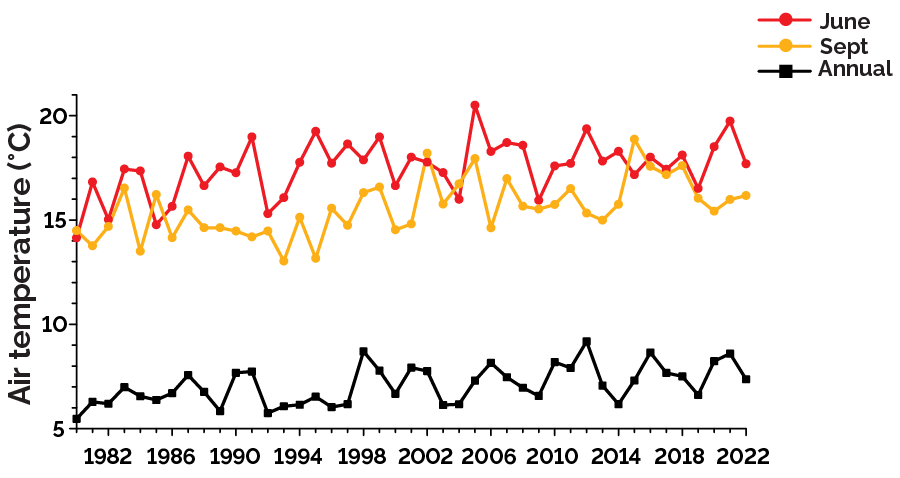

Annual air temperature data collected at Shanty Bay station by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) continue to show a significantly increasing trend. Between 1980 and 2022, there was a 0.04°C/year increase that increased air temperatures by 1.9°C. There was a significant increase in temperature in June and September of 0.04 and 0.05°C/year, respectively (Figure 10).

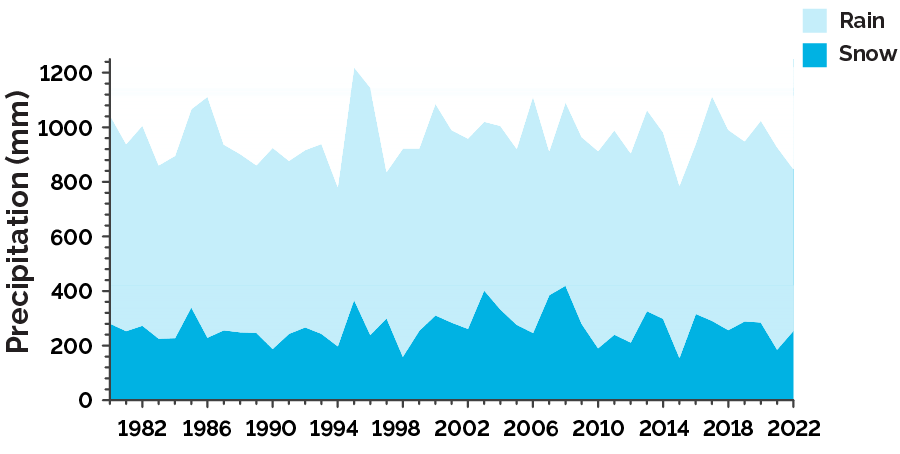

The amount of rain, snow or total precipitation did not change significantly from 1980 to 2022 at the Shanty Bay station as monthly or annual averages (Figure 11). However, it is expected that the projected warmer air temperatures will result in a greater proportion of rainfall relative to snowfall, with more frequent and intense precipitation events (LSRCA 2024). There have been notable changes in streamflow due to changes in precipitation patterns. In particular, there have been longer periods of low flow, and more intense periods of high flow and these are expected to increase.

Lake temperature during ice-free months

The effect of climate change continues to be very apparent on Lake Simcoe. In particular, the patterns of warming and cooling of lake water have shifted to earlier and later in the season, respectively.

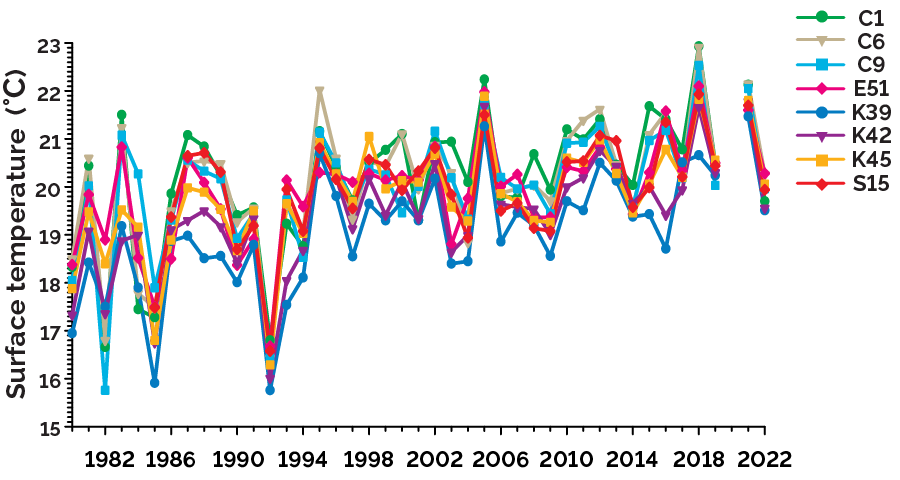

With increasing air temperatures, the average surface water temperature of Lake Simcoe (measured 1 m below the surface) from June through September has increased significantly at all lake stations since 1980 (Figure 12). Months with a significant increase in surface temperature were July, August (except at stations C1 and K45) and September.

As water temperatures warm in the spring, deep temperate lakes such as Lake Simcoe separate into 3 horizontal layers:

- warm surface layer (epilimnion)

- middle layer in which temperature declines rapidly with depth (metalimnion)

- cooler bottom layer (hypolimnion)

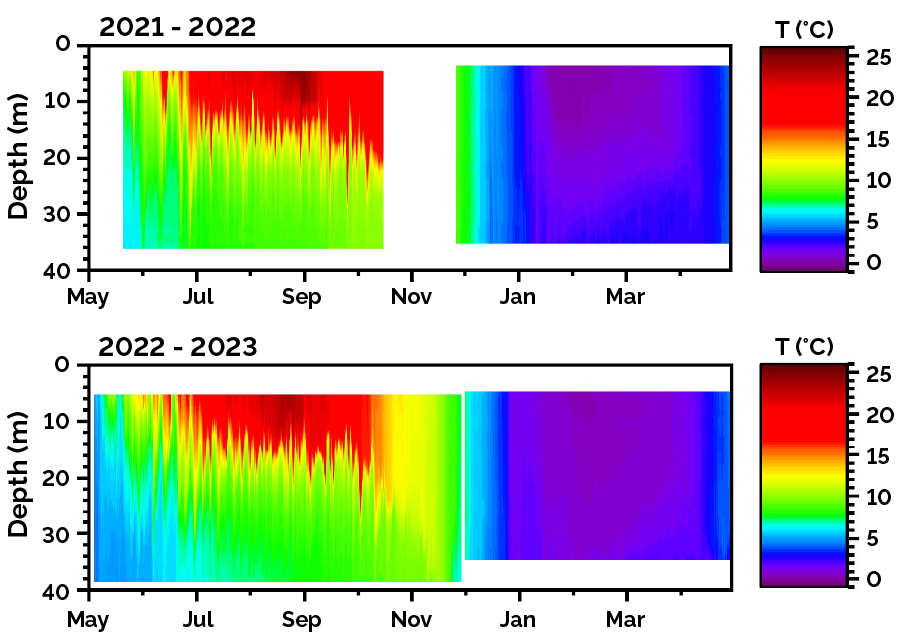

The separation of the lake into different temperature layers is called stratification, which is illustrated for the summer of 2021 and 2022 at station K42 in contour plots from high-frequency data loggers (left side of Figure 13).

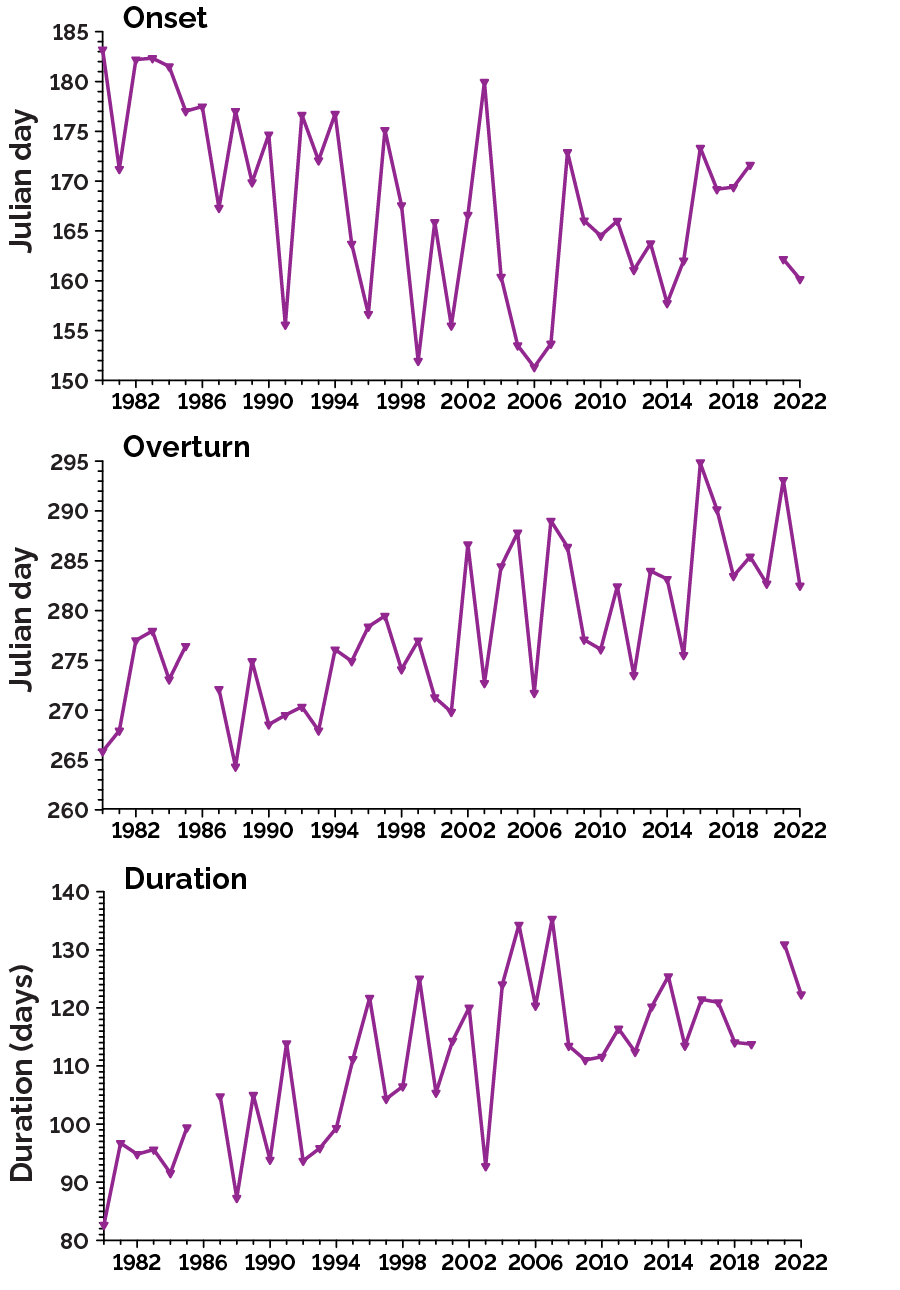

With warming spring air temperatures, the onset of stratification of Lake Simcoe into these separate layers has occurred significantly earlier since 1980 with an overall change of 23 days. Similarly, the timing of the breakdown of stratification or “overturn” of Lake Simcoe has also changed (Figure 14). When surface waters cool in the fall, they become denser and start to sink. As a result, the water column becomes less stable and easier for wind to fully mix. The date of overturn reported here was when the stability was low enough (800 J/m2 or “joule per square metre”) that the lake could become fully mixed meaning the lake had the potential to turn over but had not done so yet. This date of potential overturn has been happening later into the fall, suggesting that actual overturn was also happening later year after year.

Changes in the seasonal water temperature patterns can greatly affect aquatic biota and the broader lake ecology. Many seasonal biological processes use temperature cues. For example, a later turnover in the fall can affect when coldwater fish spawn (see below). In addition, many other processes in the lake, such as those that alter nutrients and dissolved oxygen, are affected by stratification and water temperatures.

Ice cover

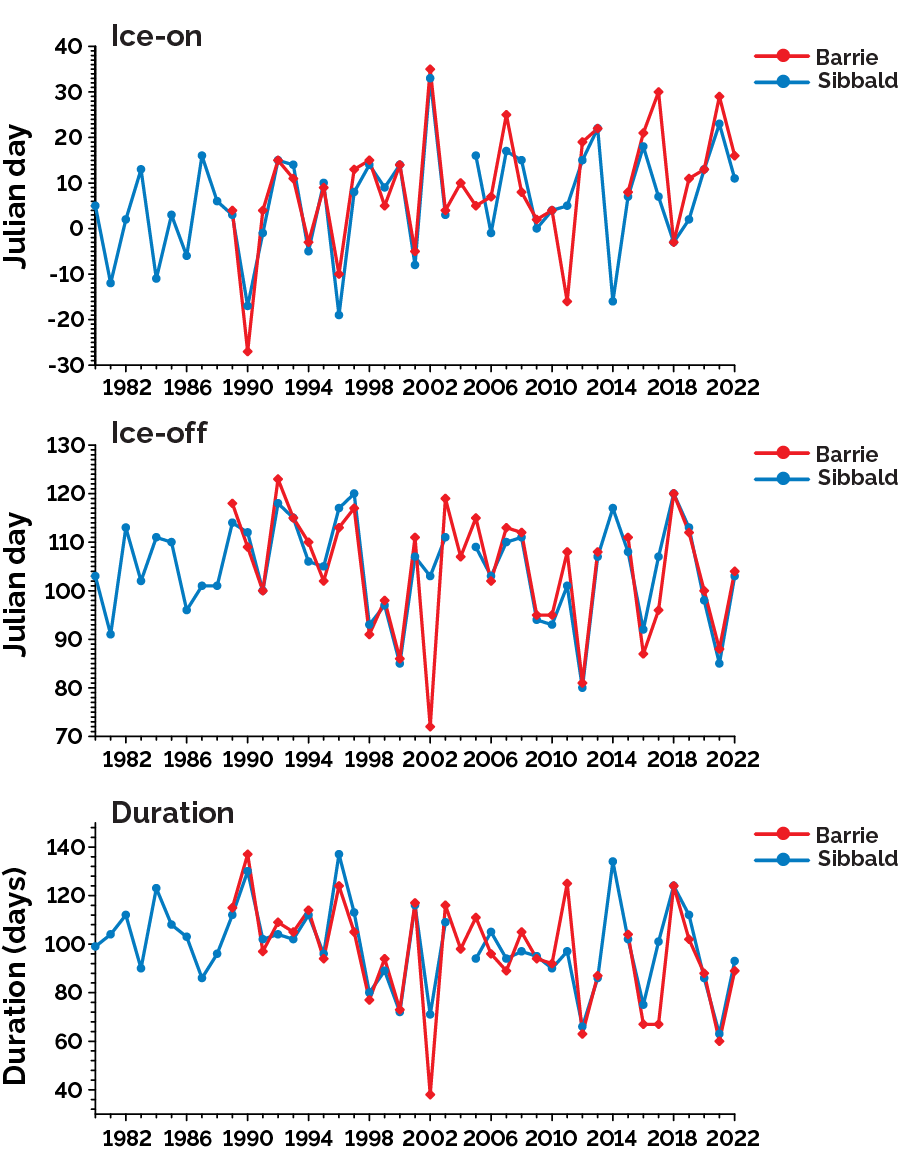

Lake Simcoe is a popular destination in the winter and can be used for ice fishing and winter recreation when the lake freezes over. However, warmer air and water temperatures have led to a delay in when the lake surface freezes (ice-on) and an advance of when the lake thaws (ice-off).

The dates of ice-on and ice-off have been recorded near Barrie (by a private citizen) since 1964 and from Sibbald Point (by the MNR) since 1989. These independent observations from different locations were relatively similar (Figure 15). Overall, the lake has been freezing later and thawing earlier, resulting in a shorter duration of ice cover. These trends were significant, except for the duration of ice cover at Sibbald Point.

From Barrie, the longest duration of ice cover observed was 137 days in 1996 and the shortest duration was 63 days in 2021. From Sibbald Point, the longest duration of ice cover observed was 137 days in 1990, while the shortest duration was 38 days in 2002 due to a very early ice-off. Over the past decade since the last report, ice duration has fluctuated substantially. For example, there was a 68-day difference in the length of ice cover between 2012 and 2014.

As winters become warmer, another consideration for lake ice is a decline in quality, which can affect both ice safety and the water quality conditions under the ice (Weyhenmeyer et al. 2022). Further research into this area is currently being supported by the province in Kempenfelt Bay, Lake Simcoe.

Complimentary to the research with University of Toronto at Scarborough is a new study with York University looking into the effect of changing winters on ice and snow conditions and how these changes influence:

- under-ice nutrients

- light availability

- water temperature

- primary production

These changes during the winter could affect important lake conditions during the ice-free season, such as spring and summer algal blooms, water temperatures and deepwater oxygen, which in turn can affect aquatic species and the food web.

Understanding water conditions under the ice

The duration that Lake Simcoe is covered with ice is about 3 months on average. This is approximately one-quarter of the lake’s annual cycle, and yet this period is still not well understood. In recent years, there has been a growing interest to study the dynamics of lakes under ice, largely because it is difficult to collect water samples in these conditions. In Lake Simcoe, the MECP have been studying under-ice temperature and oxygen dynamics using high-frequency data loggers since the winter of 2014 in collaboration with the University of Toronto at Scarborough.

Lake Simcoe experiences 2 periods of circulation patterns under the ice (Yang et al. 2020). In early winter (the first months after ice-on), the lake is usually covered by thick and/or white ice, thus there is no incoming solar radiation to heat the surface waters or promote photosynthesis by phytoplankton and aquatic plants. During this period, the only input of heat is from the sediments and incoming river water, so the water warms from the bottom where oxygen levels can decline. In late winter or early spring when the ice and snow cover starts melting, the water below the ice starts warming from incoming solar radiation, driving large scale mixing beneath the ice that gradually leads to the deepening of this warm surface layer. Changes to the duration and thickness or quality of snow- and ice-cover resulting from a changing climate could alter the timing of these dynamics, which increases the need to further understand this important time of year as it becomes shorter.

Lake Simcoe was one of many lakes included in a study that introduced a new classification system for the winter thermal structure of lakes: cryo-mictic vs. cryo-stratified (Yang et al. 2021). Lake Simcoe, along with other lakes with a large surface area that exposes the lake to more wind, is colder and well mixed before it ices over and thus it was classified as a “cryo-mictic” lake. Smaller lakes, such as Harp Lake, Ontario, that are not well mixed before freezing over were termed “cryo-stratified”. This classification provides insight into winter habitat conditions for fish and plankton. It also helps identify how climate change may affect seasonally ice-covered lakes depending on their classification. For example, the way a lake is thermally structured under ice will affect how it responds to changes in heat input from solar radiation during late winter and early spring.

Climate change indicator

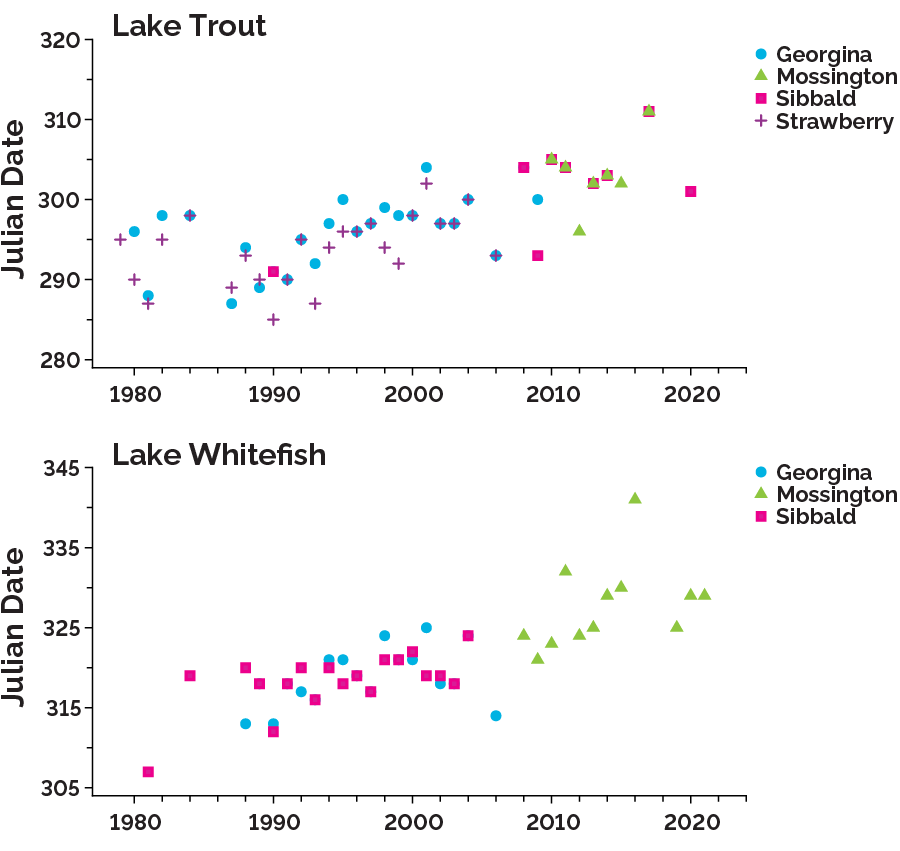

Changes to the lake due to changes in climate can have significant effects on lake biota. A climate change indicator in the LSPP is “the timing of seasonal processes like fish spawning”. In the 5-year monitoring report, data were provided that suggest delays in the halfway date of lake trout spawning from 1979 to 2003 that were correlated with increases in air and water temperature. This report shows changes over time in the first day of egg collection of lake trout and lake whitefish. While egg collection projects were designed for the sole purpose of egg collection and were not standardized to calculate spawning timing, their data are treated here as a proxy for the start of the spawning period for each of these species.

Both lake trout and lake whitefish spawn in the fall along Lake Simcoe’s shoals, and some of their eggs are collected during spawning by the MNR for future stocking purposes. Data from 1979 to 2022 show that the date of first egg collection for both species has been delayed (Figure 16). Overall, the collection of lake trout eggs was 0.37 days later per year (roughly one day later every 3 years), and the collection of lake whitefish eggs was 0.45 days later per year (roughly 1 day later every 2 years). The best model for predicting the date of first egg collection included the date of fall turnover at station K42, water temperature (3rd week of October for lake trout and 3rd week of November for lake whitefish) and sampling site. Two of the sampling sites (Sibbald Point and Mossington Point) were only sampled after 2008, so it is likely that sampling site reflected a change over time and not differences between the sites themselves. These data provide evidence suggesting that the start of spawning of lake trout and lake whitefish in Lake Simcoe has been delayed by warming water temperatures and later fall turnover.