Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy: Second progress report

Read about the actions we’ve taken under the Great Lakes Strategy to improve the environmental, social and economic health and wellbeing of the Great Lakes.

Message from the minister

As someone who lives along Lake Ontario, I am very proud to call the Great Lakes region home. There is an incredible natural legacy in these lakes and rivers, and they are central to the quality of life and strong industry that we enjoy in our province. The Great Lakes support almost 40% of Canada’s economic activity and are a vital source of safe drinking water for most of our province. They also hold great historic and cultural significance. First Nations peoples have maintained a strong spiritual and cultural relationship with the Great Lakes and the Basin is where Métis identity emerged in Ontario.

Ontario continues to take action to protect, conserve and restore the Great Lakes, and one of the ways we are doing this is through Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy. The strategy was introduced in 2012 and includes initiatives from 16 provincial ministries to further the environmental, social and economic health and well-being of the Basin.

This is the second progress report on the actions we’ve taken under the strategy, and it shows the considerable progress we are making to safeguard the Great Lakes.

In the pages that follow, you will read about how Ontario is investing in local actions and supporting partnerships to restore and protect wetlands and wildlife. You will also gain a better understanding of the economic importance of agriculture in the Great Lakes Basin, and the agri-environmental stewardship programming delivered by Ontario that focuses on positive outcomes for soil health, water quality and climate change.

This report also details how Ontario’s investments in stormwater and wastewater management will make a difference in improving water quality and outlines how we have supported municipalities and communities around the Basin to prepare for, and adapt to, climate change.

Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy is a living document, and we will continue to update it to meet the latest challenges. A review of the strategy is underway, and we will engage the Great Lakes community and partners in this process to ensure the updated strategy is reflective of the needs of the Basin today and for years to come.

While much work remains to be done, this report shows that our efforts are making a difference. We will continue working together with all the Great Lakes community partners and the public to protect the health of the Great Lakes so they can be enjoyed today and for generations to come.

The Honourable David Piccini

Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

Introduction

Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy (also known as the strategy

) was introduced in 2012 to ensure the Great Lakes continue to provide clean water to drink and where it is safe to go swimming and fishing. The strategy identified six goals to protect and restore the health of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River Basin:

- Engaging and empowering communities

- Protecting water for human and ecological health

- Improving wetlands, beaches and coastal areas

- Protecting habitats and species

- Enhancing understanding and adaptation

- Ensuring environmentally sustainable economic opportunities and innovation

The Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015, requires that the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks maintains the strategy and report on, among other things, actions that have been taken to address the priorities identified in the strategy. In 2016, Ontario reported on the accomplishments achieved in the first three years of implementing the strategy in its first progress report. The second progress report is intended to be read in conjunction with the first report as it highlights achievements made since that first report to early 2022, and encompasses actions and efforts across the 16 Great Lakes ministries:

- Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

- Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade

- Education

- Energy

- Environment, Conservation and Parks

- Finance

- Municipal Affairs and Housing

- Indigenous Affairs

- Health

- Infrastructure

- Intergovernmental Affairs

- Mines

- Natural Resources and Forestry

- Northern Development

- Tourism, Culture and Sport

- Transportation

Goal 1: Engaging and empowering communities

The Great Lakes, St. Lawrence River and their surrounding lands and waterways give us a high quality of life, and their importance to the people of Ontario is reflected in the number of individuals, communities, and organizations that contribute to their protection and restoration. First Nations peoples have lived and thrived in the Basin for millennia, relying on the lakes as a source of food and water, and building cultural and spiritual relationships with the land and water. The Anishinaabe people, many who continue to live in the Basin today, identified the Great Lakes as Nayaano-nibiimang Gichigamiin, which means the five freshwater seas

in the Anishinaabemowin language. The Mohawk people have long-standing ties to the St. Lawrence River Valley, and the St. Lawrence River is also known as Kaniatarowanenneh, which is Mohawk for the ‘big waterway,’ or River of the Iroquois.

The purpose of engaging and empowering communities is to create opportunities for individuals and communities to become more involved in the protection and restoration of the ecological health of the Great Lakes Basin. Actions in the strategy include supporting collaboration and partnerships with governments and with First Nations and Métis communities, building awareness, and supporting community action.

Collaboration and partnerships

Supporting and engaging in collaboration and partnerships with the broad Great Lakes community to generate awareness and local action on the Great Lakes is a key component of the Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy.

Ontario continues to collaborate with Canada and other Great Lakes jurisdictions by being an active participant, advisor and/or member on numerous commissions, councils and committees, such as the:

- Great Lakes Executive Committee under the Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement

- The Executive Committee under the Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health

- Great Lakes Commission

- Great Lakes Fishery Commission

- Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers

- Regional Body of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement

- International Joint Commission committees, boards and tasks teams

In addition, Ontario continues to collaborate with various agencies and other partners, such as academia, to advance our knowledge and scientific understanding through identification of science priorities, such as participating in the State of the Lake Conferences to report on findings and identify science priorities and future work, participating in the Great Lakes Mapping Coalition, providing data and information to support assessments, priority setting, and day to day collaborations on Great Lakes projects.

Collaboration with First Nations and Métis partners to protect, restore and conserve the Great Lakes Basin is a particularly important component of the strategy. The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks has worked with First Nations communities to support a range of Great Lakes projects and initiatives, including community-based monitoring, habitat and species restoration efforts, shoreline cleanups, gatherings with First Nations youth and Elders and supporting Traditional Ecological Knowledge. This has included work led by M’Chigeeng First Nation, Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, Walpole Island First Nation and Magnetawan First Nation, who each hosted Traditional Ecological Knowledge workshops to support the development of Indigenous Knowledge databases. Other community-led projects, such as work led by Red Rock Indian Band, have helped to map valued ecosystem components and support watershed management and climate change adaptation planning. Ontario’s other Great Lakes ministries also continue to work with First Nations and Métis and play an integral role in collaboratively advancing Great Lakes protection and restoration efforts.

Other examples of collaborative efforts among the Great Lakes community to address priority issues in the Great Lakes Basin include:

Groundwater chemistry mapping on Manitoulin Island

In 2017, the Ontario Geological Survey collaborated with local Indigenous communities to carry out a groundwater chemistry mapping campaign on Manitoulin Island, resulting in mutually beneficial information and resource sharing. Community members shared knowledge of groundwater spring locations to inform sampling locations, and results were provided to homeowners and community members. The project helped the province characterize groundwater geochemistry of the major rock and overburden units in Ontario, and provided water quality information to community members.

4R Nutrient Stewardship Program

Following the initiation of the partnership in 2015, Fertilizer Canada partnered with OMAFRA, the Ontario Agri Business Association, Grain Farmers of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Agriculture, and Christian Farmers Federation of Ontario to implement the 4R Nutrient Stewardship (Right Source @ Right Rate, Right Time, Right Place®) program in Ontario. In 2018, the voluntary 4R Certification program was launched and works to audit agri-retailers, independent consultants and other certified professionals on their ability to recommend and apply 4R Nutrient Stewardship principles with their grower customers. 4R Nutrient Stewardship balances farmer, industry, and government goals to improve on-farm economics, crop productivity and fertilizer efficiency and retain nutrients on-field to reduce excess loss to the environment. As of March 2022, 24 sites were certified through the program, verifying over 590,000 acres of farmland in Ontario and 2,500 farms as following 4R Nutrient Stewardship.

Canadian Agricultural Partnership

The Canadian Agricultural Partnership (Partnership) is an investment by federal, provincial and territorial governments to strengthen and grow Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sector. The Partnership provides funding (from Canada, and Ontario) to support region-specific agriculture programs and services tailored to meet regional needs. An example of programming offered in Ontario under the Partnership is the Lake Erie Agriculture Demonstrating Sustainability (LEADS) initiative, a five-year (2018–2023), $15.6 million investment that helps farmers take action to improve soil health and water quality in the Lake Erie watershed.

Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program

The Green Infrastructure stream of the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program has been used to leverage existing funds to make infrastructure improvements in communities on the Great Lakes. In 2018, Ontario and Canada signed an agreement for $11.8 billion in federal funding across specific program streams. Under the first intake in October 2019, $200 million in federal-provincial funding was allocated towards projects addressing critical health and safety issues associated with water, wastewater and stormwater infrastructure, such as improvements to the City of Belleville’s municipal stormwater pumping station, and conversion of a combined sewer in Leamington to separate stormwater and wastewater mains. This also included 41 projects with First Nations communities, such as drinking water treatment improvements for Pays Plat First Nation and the construction of a new water treatment plant for the Biigtigong Nishnaabeg First Nation. Under the second intake in July 2021, $330 million in federal-provincial funding was allocated towards critical health and safety issues associated with drinking water infrastructure, with 10% of the available funding allocated towards First Nations community projects.

Great Lakes Guardians’ Council

The Great Lakes Guardians’ Council, established under the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015, is a unique forum for provincial, municipal, First Nations and Métis leadership representatives that have a historic relationship with the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin. It also includes representatives from the science community, environmental groups, agriculture, industry, recreation and tourism sectors. The purpose of the Council is to identify and find solutions to Great Lakes challenges, increase the science and consideration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and strengthen our shared understanding of the Great Lakes. The Council is co-chaired by the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, and a representative from Indigenous leadership. To date, the Council meetings have been co-chaired by the Grand Council Chief of Anishinabek Nation.

Following the inaugural meeting on March 22, 2016, at the suggestion of the former Chief Water Commissioner, Anishinabek Women’s Water Commission, Josephine Mandamin, the Council gathered on Manitoulin Island on August 21–23, 2016. The purpose of this gathering was to build relationships, foster discussion on Great Lakes priorities, and build a foundation for the Council’s work going forward. Participants were encouraged to share stories of the lakes and foster cross-cultural learning and partnership on Great Lakes protection activities and initiatives.

It was noted that the Great Lakes are a unifying concept for people who live in Ontario. Some of the key themes of the discussion included the importance of connecting people to the lake, education on the Great Lakes and treaties, and the use of information — including Traditional Ecological Knowledge — for better decision making. The Council has met seven times since the inaugural meeting, and most recently met on April 22, 2021.

Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health

Implementation of Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy is a collaborative effort across government, with multiple ministries coming together to implement actions to support environmental, economic and social goals for the Great Lakes Basin. Collaboration with Canada is a key component of addressing Ontario’s strategy commitments, and this relationship is coordinated through the Canada-Ontario Agreement (COA) on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health. COA assists Ontario in meeting its goals in Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy and helps Canada meet its obligations under the Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

The 2014 COA was in effect from 2014 to 2019 and led to significant progress in protecting and restoring the Great Lakes. In addition to many activities included in this report, examples of key accomplishments under the 2014 COA include:

- completion of the Great Lakes Nearshore Framework

- identification of priority areas and collaboration with partners on initiatives to improve nearshore areas, such as the Western Lake Ontario Land to Lake Initiative, the St. Lawrence River Strategy and the Southern Grand Rehabilitation Initiative

- completion of projects across the Basin to support research, monitoring and reporting of native fish, aquatic wildlife, food webs and habitats, such as an assessment of the Lake Ontario lower food web, monitoring of Atlantic Salmon using multi-sensor technology, and restoration monitoring for Lake Trout, American Eel and Lake Sturgeon

- support of focused opportunities for participation and collaboration with First Nations and Métis in Areas of Concern (AOCs)

- establishment of Lake Erie phosphorus reduction targets and development of the Canada-Ontario Lake Erie Action Plan

- implementation of a First Nations Youth Program on the Thames River

- support of Traditional Ecological Knowledge pilot projects related to Great Lakes protection and restoration

Lake-by-lake examples of recent accomplishments undertaken by Ontario and partners under the 2014 COA

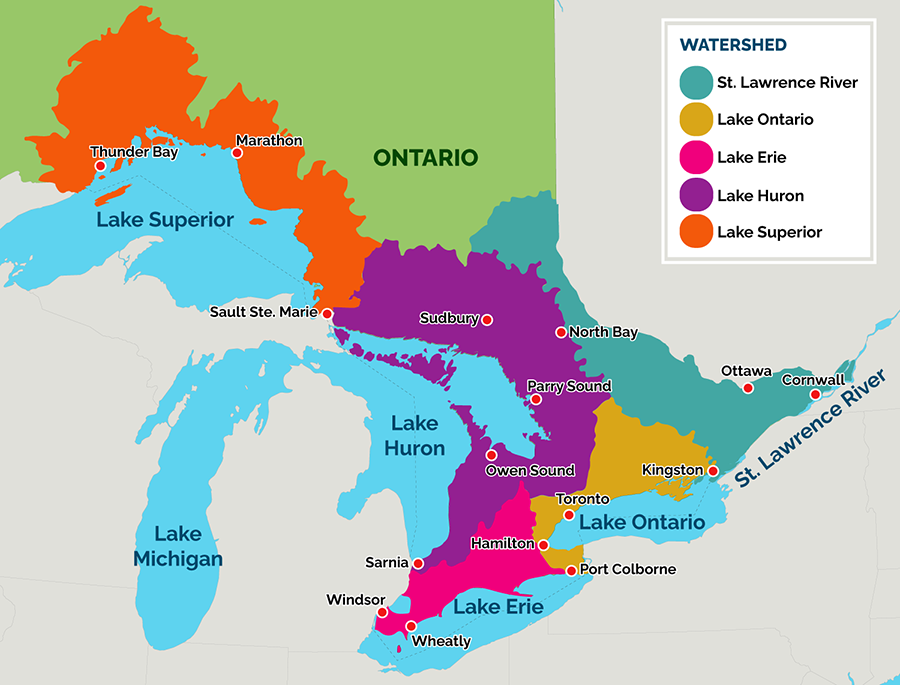

The Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River Basin in Ontario

The map shows the five Great Lakes, four of which are in Ontario (Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron and Superior), and the St. Lawrence River. Coloured shading is used to show each of the watersheds of the respective lakes and river.

Lake Superior

A recent example of continued progress on addressing legacy contaminated sediments in the Great Lakes is the application of a thin-layer sediment cap to Jellicoe Cove, the area with the highest mercury concentrations, in the Peninsula Harbour Area of Concern in Lake Superior (Anishinaabewi-gichigami in the Anishnaabewowin language). The Harbour is identified as an AOC due to historical inputs from the pulp mill and chlor-alkali plant, and log booming. Decades of industrial activity has resulted in elevated levels of mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in sediment. The science indicated that a 15–20 cm sand cap over the contaminated sediment would accelerate natural recovery of the site by 75 years. Since its application in 2012, monitoring has shown that the cap has been effective and met the objectives of the remedial effort. It reduced the movement of mercury and PCBs to the overlying waters and the exposure of aquatic organisms to mercury in sediment, which is below the clean-up target. As a result, the Degradation of Benthos Beneficial Use Impairment was redesignated in January 2022 to “not impaired.” In addition, two other impairments to the AOC — Degradation of Fish and Wildlife Populations, and Loss of Fish and Wildlife Habitat — were designated “not impaired” in 2021.

Lake Huron

Since 2010, Ontario, Canada, municipalities, conservation authorities, non-governmental organizations and others have worked together to coordinate actions to protect and improve water quality along the southeast shores of Lake Huron. The Healthy Lake Huron Initiative aims to reduce the amount of nutrients and bacteria entering the water in six priority watersheds. Since 2018, over 75 projects and approximately $4 million dollars have been invested in the area. Examples of recent projects include the installation of stream buffers, berms, and use of cover crops to reduce soil loss and improve soil health; septic system inspections and upgrades; and restricting livestock from streams. Outreach and education are undertaken through annual newsletters, a projects website, landowner workshops and one-on-one visits and demonstrations. Long-term monitoring in these watersheds shows some improvements over time.

Lake Erie

First Nations have a strong cultural and spiritual connection to Deshkan Ziibi (from the Anishnaabewowin language), or the Thames River, which flows into Lake St. Clair and is part of the Lake Erie basin (Waabishkiigoo-gichigami). The Thames River Clear Water Revival (TRCWR) is a long-running partnership between the First Nations with traditional territories in the watershed, the City of London, the Lower Thames Valley Conservation Authority, the Upper Thames Conservation Authority, Ontario and Canada. Ontario has supported a number of TRCWR projects, most notably a First Nations Youth Program launched in 2015 to: provide First Nations youth with an awareness and appreciation of work opportunities in the environmental field; improve connections between communities; and advocate for environmental issues. The information gathered as a part of this initiative also informed a 20-year plan to protect and restore the watershed water quality and quantity, while supporting economic and urban development.

Lake Ontario

Within the Hamilton Harbour AOC in Lake Ontario (Niigani-gichigami), Randle Reef sediment is highly contaminated with polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), as a result of over 150 years of historical industrial inputs. There is an ongoing $139 million restoration project to contain the contaminated sediment in an underwater steel box. Hydraulic dredging of the contaminated sediment was completed in October 2021. The project will be entering its final phase, with the installation of the isolation cap for the steel box. The project is funded by Canada, Ontario and local partners. When the project is completed in 2024, the environmental, economic and social benefits will be numerous, including improved fish and wildlife habitat, reduced spread of contaminants through the harbour, enhancement of recreational, shipping and port opportunities, and an estimated economic impact to the community of $126 million in job creation, business development and tourism. The project is also essential to delisting Hamilton Harbour as an AOC.

St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River, or Kaniatarowanenneh in the Kanien’kéha language, has a significant connection to the cultural identity and rich history for Indigenous peoples that have lived along the river for millennia. The Mohawk community of Akwesasne, meaning Land Where the Partridge Drums

is located along the river in Akwesasne, near Cornwall, Ontario, which is an AOC. One of the most harmful aspects of the contamination in the St. Lawrence River was the fear it created among Akwesasr:onon to engage in practices with the water, fish, and land. The maintenance of Akwesasr:onon cultural knowledge and values is contingent on being connected with the land through land-based practices. In 2021, Ontario and Canada funded a project called “St. Lawrence/Cornwall Area of Concern — Fish Consumption and Sampling Community Input” to analyze fish species of interest for contaminants and provide up-to-date information on contaminant levels for Akwesasne to review and distribute to the community. The project also supports the facilitation of workshops that will include open discussions about fish species of interest, environmental fears, cultural responsibilities to the fish, and what is needed to repair the disconnect between Akwesasr:onon and the water and fish. The project will help determine if consumption of fish and wildlife is still impaired within the St. Lawrence River AOC.

Following many months of negotiations, on May 27, 2021, Canada and Ontario signed the 9th Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, marking more than 50 years of collaboration between Canada and Ontario to improve conditions in the Great Lakes. The 2021 COA sets out specific actions that each government will take as they work together to restore, protect and conserve the water quality and ecosystem health of the Great Lakes. The 2021 COA outlines new and ongoing actions to safeguard the world’s largest freshwater lake system, such as improving wastewater and stormwater management, managing nutrients, reducing plastic pollution and excess road salt, restoring native species and habitats and increasing climate resilience. The agreement also includes a new focus on protecting Lake Ontario and supporting nature-based recreation opportunities.

In addition, Ontario is committed to both new and continued actions to support engagement of First Nations and Métis partners as they continue to provide local community context, knowledge, expertise and resources that help to inform future collaborative efforts for Great Lakes restoration, protection and conservation. The 2021 COA maintains the specific First Nations and Métis Annexes introduced in the 2014 COA, directs all Annex Leads to collaboratively engage First Nations and Métis partners in the delivery of Annex commitments, as appropriate, and makes a series of new commitments throughout the agreement.

Building awareness

Ontario works to increase awareness of the Great Lakes by forging new partnerships between conservation authorities, non-governmental organizations and school boards. Educational events such as mini-water festivals, virtual field trips, student conferences and multi-day student summits have been co-created and delivered by partners since 2016. Recently, Ontario adapted its Great Lakes student/teacher conference model to fund virtual field trips to the Great Lakes, which supported Ontario’s switch to remote learning. The virtual field trips include: Lake Superior, Georgian Bay/Lake Huron, the Lake Huron/Lake Erie connecting channel and Ottawa River/St. Lawrence River.

Ontario’s provincial parks provide a way for many people to interact with and enjoy the Great Lakes. Over 20 parks in the Great Lakes Basin have senior interpretative naturalist staff who deliver programs to hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

Ontario Parks recently partnered with Canadian Geographic to produce giant floor maps and lesson plans for use as a teaching resource, one of which highlights Ontario’s waterways and the Great Lakes. In addition, Ontario Parks’ Discovery School Program reaches tens of thousands of children annually, and parks along the Great Lakes such as Pinery Provincial Park and Bronte Creek Provincial Park host school group field trips.

Supporting community action

Ontario launched the first round of the Great Lakes Local Action Fund in September 2020 to support local projects that protect and restore coastal, shoreline and nearshore areas of the Great Lakes and their connecting rivers and streams. In 2021, 44 projects were selected to receive funding totaling $1.9 million over two years. The projects are led by community-based organizations, municipalities, conservation authorities and Indigenous communities and organizations across Ontario, from Ottawa to Thunder Bay. Some of the recipients include:

- ALUS Norfolk, who worked with farmers to restore land to reduce agricultural impacts on Lake Erie

- the City of Pickering, in collaboration with 50 community and youth groups, cleaned up litter along the shorelines and tributaries of Lake Ontario

- Manitoulin Streams Improvement Association, in partnership with Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, worked to restore habitat, improve water quality and clean up the shoreline of a Lake Huron tributary

- I-Think developed a Great Lakes Challenge Kit, which trains teachers on expanding teaching practices to include Great Lakes issues in student lessons

On February 7, 2022, Ontario announced an additional $1.9 million investment in the Great Lakes Local Action Fund. This new investment will support local projects led by community-based organizations, small businesses, municipalities, conservation authorities, and Indigenous communities and others that focus on protecting and restoring coastal, shoreline and nearshore areas of the Great Lakes and its connecting rivers and streams.

Read the measuring progress section of this report for more information on Ontario’s progress in engaging and empowering communities in the Great Lakes.

Goal 2: Protecting water for human and ecological health

The purpose of this goal is to protect human health and well-being through the protection and restoration of the ecological health of the Great Lakes Basin. The strategy includes actions to:

- manage and protect drinking water

- identify and mitigate impacts to water quality

- manage water usage and adapt to lake level changes

Management and protection of drinking water

Collaboration with municipalities, conservation authorities, source protection committees and others to support effective and ongoing implementation of source protection plans is a key commitment in the strategy to manage and protect drinking water. As highlighted in the Minister's annual report on drinking water (2021), implementation of 38 collaborative, watershed-based source protection plans that protect existing and future sources of drinking water is underway across Ontario. These plans contain policies to address certain activities identified as threats to drinking water sources, which include the Great Lakes. Approximately 39% of surface water drinking water systems which connect to the Great Lakes are included in source protection plans.

For example, the Essex Region Source Protection Area has formally identified the toxin produced by blue green algae, called microcystin-LR, as a drinking water issue at all Lake Erie drinking water intakes. The identification of activities and areas that contribute to this issue are being considered through the source protection plan, and can be adapted if required in the future.

In addition, the Credit Valley — Toronto and Region — Central Lake Ontario Source Protection Plan includes policies to specify actions to mitigate spill risks from fuel storage, pipelines, and nuclear power generation.

In 2017, an approach was added to the Technical Rules made under the Clean Water Act, 2006 to allow individual source protection committees and authorities to better identify water quality risks to drinking water systems in larger water bodies such as the Great Lakes that can be more vulnerable to contamination in a nearshore environment. In 2021, further changes were made to the Technical Rules to consider climate change risks, improving the risk-assessment approach to better identify risks associated with road salt, and the handling and storage of toxic chemicals.

To help ensure communities and landowners with drinking water systems not covered by provincially-approved source protection plans have the tools they need to continue to protect their drinking water sources, the province released new best practices for source water protection on ontario.ca on February 18, 2022. The new user-friendly best practices provide easy-to-understand information and tips to help private landowners, such as farmers and cottagers, First Nations communities, and communities protect drinking water sources from contamination. This includes ensuring a septic system is functioning properly and that on-site fuel tanks and pesticides are stored safely.

First Nations Drinking Water

The Ontario Clean Water Agency (OCWA) has established a First Nations Advisory Circle to gain a greater understanding of the broader water issues facing First Nations communities from an Indigenous perspective. The Advisory Circle, which reports to OCWAs Board of Directors through the Board’s First Nations Committee, meets at least four times annually and is comprised of a diverse group of individuals that identify as Indigenous, representing a variety of backgrounds, experiences and communities. The Advisory Circle provides advice and recommendations on the integration of First Nation perspectives into the OCWAs strategies and how the OCWA can enhance its partnerships with First Nations communities to better support their water and wastewater needs and concerns. The goal of the Advisory Circle is to provide a better understanding of the challenges that First Nations face, not only with respect to addressing water and wastewater treatment in their communities, but also in the context of their unique experiences, culture and history in Canada. The OCWA is committed to strengthening its current First Nations partnerships and developing new partnerships based on mutual trust, respect and collaboration.

Through the Walkerton Clean Water Centre (WCWC), Ontario has also been working with First Nations on the development of training programs to support operators, managers and community leaders in maintaining safe drinking water systems. Between April 2017 and March 2022, 167 individuals successfully completed the Entry-Level Course for Drinking Water Operators for First Nations,

and 116 successfully completed Managing Drinking Water Systems in First Nation Communities.

This training is provided in-kind and at no cost to the communities. WCWCs courses help build capacity and have been positively received by First Nation participants and communities, who we have heard want to see this relationship continue.

Read the measuring progress section of this report for more information on Ontario’s performance in ensuring drinking water in the Great Lakes Basin meets a high standard of safety.

Identifying and monitoring impacts to water quality

Research and monitoring are needed to identify impacts to water quality to inform management actions. The strategy commits Ontario to work to address water quality issues, including harmful and nuisance algal blooms, as well as toxic chemicals of emerging concern. Since the first progress report in 2016, Ontario has continued to invest in and support activities to identify and understand impacts to water quality in the Great Lakes Basin.

Collaborative Lake St. Clair and Thames River water quality study

Ontario, in partnership with Canada, collaborated with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Great Lakes Institute of Environmental Research and Lower Thames Valley Conservation Authority to assess the water quality of Lake St. Clair and the Thames River. This multi-year collaborative study confirmed the presence of harmful algal blooms, which can occur extensively along the Canadian shoreline of Lake St. Clair and the lower Thames River.

Lake Erie phosphorus studies

Studies by the Ontario Geological Survey, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks and additional partners examined levels of phosphorus in Lake Erie and its tributaries, as well as modelled lake-wide phosphorus and annual internal phosphorus loading, to enhance understanding of conditions in the lake and the role of nutrients in causing algal blooms.

Urban impacts studies

Recent studies in Lake Ontario by the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks used monitoring data and modelling to examine water quality, nutrient patterns and lake circulation to develop a proposed study framework to assess urban effects on the lake and the interaction of the land and water, and to help support the design of solutions.

The Multi-Watershed Nutrient Study

The Multi-Watershed Nutrient Study was conceived as a response to algae blooms and other signs of excess nutrients in the Great Lakes.

The main goals of the study included investigating the changes from the 1970s to today in:

- Diffuse sources of nutrients from agriculture

- The relationship between agricultural land use / management and nutrient inputs to water bodies

- Seasonal patterns of nutrient inputs to water bodies

- The types and ratios of phosphorus that are coming from agricultural landscapes

In addition, the study was designed to gauge the scope for change in the amount of nutrients coming from diffuse agricultural sources.

The study included:

- 4 continuous measurements

- 11 sentinel watersheds

- 15 million+ data points

- 55 tests per water sample

- 1800+ water sampling events

- 8 meteorological stations

- 10 parameters per station

- 5 years of sampling

- 3 university partners

- 12 research projects

Early findings of the study show that compared to a similar study in the 1970s:

- Nutrient inputs to water bodies have increased overall at most study sites

- Inputs of nutrients to water bodies have shifted to being mainly during the non-growing season in many areas, instead of the growing season as before

- More water is moving through some watersheds now

- There is now better information to model nutrient information in Ontario

Pesticides in stream water

Ontario’s Pesticide Concentrations in Stream Water study analyzes approximately 500 pesticide compounds in 18 Great Lakes tributaries dominated by agricultural land use. The results from this program have the potential to demonstrate the effectiveness of watershed management programs, policies and regulations, and illustrate areas where continued vigilance is needed.

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) monitoring

Ontario’s Great Lakes monitoring has demonstrated that concentrations of PCBs in sediments have declined in some nearshore areas of Lake Ontario since 1994. On average, levels of PCBs in sediments at the sixteen sites that were sampled over this time period have decreased by half, and there were significant improvements in some Areas of Concern, such as the Toronto Inner Harbour. However, there are areas where PCB concentrations remain elevated, particularly in areas closer to shore and near urban areas. The data suggests that concentrations of PCBs in Lake Ontario surface sediments should continue to decline with reduction of inputs to the lake.

New technologies to support monitoring

New techniques and technologies have also been used to support monitoring efforts. For example, real-time monitoring buoys deployed in the nearshore of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario provide an opportunity for early warning of water quality issues. Recently, data from monitoring buoys are being made available via a new data sharing platform called Seagull. Making the data accessible through this platform will facilitate its use by researchers in both Canada and the U.S. — for example, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently used this data to develop a model to help predict movements of low-oxygen water in Lake Erie, which can impact fish populations and water quality at drinking water intakes.

A real-time monitoring buoy in the nearshore of Lake Ontario

In addition, the use of passive samplers has enhanced monitoring of contaminants of ongoing and emerging concern. Passive samplers are devices that can be placed and left in water or sediment to assess concentrations of chemicals. These devices have been used at Great Lakes long-term monitoring sites and watersheds, to track down sources of legacy contaminants such as PCBs in Hamilton Harbour, for monitoring historical contaminants in the Niagara River region, and evaluating the effectiveness of remediation in Peninsula Harbour. Passive samplers are also very useful for enhancing monitoring for contaminants of emerging concern, such as flame retardants, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides, and their use has allowed us to screen for unknown contaminants and prioritize for further assessments, such as contaminants from the breakdown of tires.

Actions to protect and restore water quality

Protecting and restoring water quality requires action on multiple fronts. The strategy strategy includes sixteen commitments to reduce stormwater and wastewater impacts, reduce excessive nutrients, and protect water quality by reducing toxic chemicals and other pollutants such as salt and plastic.

Excess phosphorus

Addressing threats to the water quality of the Great Lakes requires sustained, collaborative effort. When excess amounts of phosphorus from urban stormwater and farmlands enter waterways, for example, this can lead to the growth of algal blooms, which is currently threatening the water quality of water bodies like Lake Erie. To address this, the strategy commits Ontario, with Canada and implementation partners, to develop and implement an action plan to reduce phosphorus loads to Lake Erie.

Under the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015, Ontario committed to a 40% phosphorus load reduction target for Lake Erie. This 40% phosphorus reduction target was established through a binational science process for the western and central basins of Lake Erie to address harmful algal blooms in the western basin and hypoxia in the central basin.

The Canada-Ontario Lake Erie Action Plan to reduce phosphorus loadings to Lake Erie was released in 2018 and identifies more than 120 actions to help achieve the phosphorus target, such as better management of wastewater and stormwater discharges, using best management practices to keep phosphorus on farmland and out of waterways, restoring natural heritage features such as wetlands, improving monitoring and science, and enhancing communication and outreach. Almost half (46%) of the actions in the Lake Erie Action Plan are designated for the ministries of Environment, Conservation and Parks, Natural Resources and Forestry, and Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Through the Canada-Ontario Lake Erie Action Plan, Ontario works with Canada and partners to implement actions towards the phosphorus reduction targets, which complements U.S. efforts to achieve binational phosphorus reduction targets for the lake. See the measuring progress section of this report for more information on progress to date in Lake Erie.

Excess salt

As reported in the last progress report, excess salt also has a negative impact on water quality in the Great Lakes Basin. A recent analysis of Ontario’s long-term chloride (an indicator of salt) data found that many monitoring locations near roadways or in urban areas exceeded the chloride water quality guideline. To act on this issue, the Ministry of Transportation’s Salt Management Plan was reviewed and updated in 2017 and now includes proven and science-based best management practices to ensure the optimal rate, timing, and location of salt application on roads. The plan ensures the best available winter maintenance practices are implemented to ensure safe driving conditions on the provincial highway network while minimizing environmental impacts.

In addition, the province works with stakeholders across Ontario, Canada and the U.S. to invest in research to understand new products and practices to deliver snow and ice control that reduce road salt usage and mitigate environmental impacts while maintaining public mobility and safety on provincial highways. Ontario has also conducted extensive research into winter materials over many years that has led to changes in winter maintenance standards and best practices, such as using pre-treated salt at lower application rates in place of dry salt.

In spring 2022, the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks held workshops with a range of stakeholders to seek input on the role of best practices in reducing excessive salting on Ontario’s roads, parking lots and sidewalks. The sessions offered a lot of helpful input and insights, including factors driving overapplication and key obstacles and challenges experienced by industry in adopting leading practices. The ministry is considering the feedback to help inform any next steps.

Collaboration and support from the Province of Ontario has been instrumental to Pollution Probe’s work related to addressing plastic pollution in the Great Lakes, which includes establishing and expanding the Great Lakes Plastic Cleanup, the largest initiative of its kind in the world aimed at preventing and removing plastic debris from the lakes. We look forward to continuing to work together for the benefit of our Great Lakes and the communities that rely on them.

Christopher HilkeneChief Executive Officer, Pollution Probe

Improvements to wastewater and stormwater management

As stormwater and wastewater are major conveyers of pollution, improvements to their management can have significant, tangible impacts on the water quality of the Great Lakes. The strategy includes four commitments to reduce stormwater and wastewater impacts to the Great Lakes, including assisting communities in reducing the volumes and impacts of stormwater; working with municipalities on solutions to minimize discharges of untreated sewage; and reducing the impacts of treated wastewater by working with communities and stakeholders to update policies, manage water infrastructure assets, and optimize wastewater treatment plants.

In addition to the Green Stream of the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program, Ontario has used multiple avenues to invest in improvements to wastewater and stormwater systems around the Basin:

- Under the Ontario Community Infrastructure Fund program, eligible communities receive stable and predictable funding to support core infrastructure priorities including road, bridge, water and wastewater (includes stormwater) projects. Wastewater projects are assessed on various criteria including minimizing discharges of raw sewage by rehabilitating or developing new wastewater infrastructure. As announced in the 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, Ontario is increasing the Ontario Community Infrastructure Fund by $1 billion over the next five years ($200 million per year) beginning in 2022.

- The Ontario government is providing nearly $10 million in funding to provide support for wastewater monitoring and public reporting, to improve transparency around monitoring and public reporting of sewage overflows and bypasses from municipal systems. The government is also providing $15 million in capital funding to improve the management of wastewater and stormwater discharges into the Lake Ontario basin.

Ontario also continues to support local groups and programs to improve management of wastewater. For example, the Grand River Watershed-Wide Wastewater Optimization Program provides wastewater treatment optimization technical support to wastewater operators and managers, and reports on improvements in the quality of wastewater discharges in the Grand River watershed. In addition, Ontario invested in optimization projects at wastewater treatment plants in Sarnia, Oxford County and Leamington, and facilitates a group of wastewater managers to regularly discuss optimization at wastewater treatment plants.

Inadequate readiness for storm events can have environmental, social and economic impacts. The insurance industry tells us that water damage from extreme weather events, such as flooding, is the key factor behind growing insurance costs. These losses across Canada averaged $405 million per year between 1983 and 2008, and have more than doubled to $1.8 billion per year between 2009 and 2017. While conventional stormwater management infrastructure can be costly, low impact development (LID) can be a cost-effective way of managing stormwater runoff because it can potentially generate a $1.60 to $2.40 return on the investment, with benefits including aesthetics, recreation, air quality, local climate regulation, improved water quality and avoided economic costs (such as stormwater treatment, mitigation costs). In order to improve our readiness, Ontario is taking a number of steps to reduce barriers for stormwater managers.

In January 2022, a draft Low Impact Development Stormwater Management Guidance Manual was posted on the Environmental Registry for public comment. The purpose of this draft manual is to provide guidance for stormwater managers on reducing stormwater volume and associated contaminant release into waterways. This will be an important step for reducing barriers to adoption of innovative, adaptation technologies for stormwater management. Ontario is committed to protecting our lakes, rivers and groundwater supply, now and for future generations. Ontario sought public input on:

- a discussion paper on potential opportunities and approaches to improve municipal wastewater and stormwater management and water conservation

- a proposed subwatershed planning guide to help municipalities and other planning authorities with land use and infrastructure planning

Another initiative that complements the overall approach for stormwater management is the proposed regulatory changes under the Ontario Water Resources Act to exempt certain low risk sewage works from requiring an environmental compliance approval (ERO 019-4456 October 25, 2021). The proposed changes, if implemented, would reduce red tape and make it easier to build LIDs by removing the need to obtain an environmental compliance approval for stormwater management LIDs located on single private residences.

Ontario funded the Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority in partnership with Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program, to advance a best practice

training program for stormwater infrastructure maintenance and inspections. Municipal stormwater management inspector training has been provided to over 100 municipal participants from the Lake Simcoe watershed and across Ontario in 2021.

Agricultural stewardship and best management practices

Ontario agriculture and agri-food sectors are an important economic engine for the province and contribute to our quality of life by providing good jobs, safe and secure food and contribute to Ontario’s economic success. Ontario provides assurance and oversight of the agri-food system to protect the productive capacity of our natural resources and support sustainable actions. Best management practices help to minimize the risks of excess nutrients to the Great Lakes. Ontario delivers agri-environmental stewardship programming to assist Ontario producers in managing soil and water impacts. The strategy commits Ontario to:

- improve understanding of the effectiveness of agricultural stewardship programs and practices

- encourage and strengthen the adoption of effective best management practices

- seek opportunities to reduce nutrient inputs to the environment and advance monitoring of agricultural best management practices in priority geographic areas and in agricultural production systems to enhance performance

Ontario provides technical support for farmers, watershed initiatives and industry groups, and invests in environmental stewardship activities to provide support to farmers in implementing best management practices. Conservation authorities and agriculture sector groups are also leading several initiatives across the Great Lakes Basin towards improving soil health and water quality. This includes one-on-one outreach, workshops and demonstration projects to increase the adoption of best management practices in high priority watersheds that will enhance water quality by reducing the excess loss of phosphorus from agriculture.

The first progress report on Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy noted the initiation of the Great Lakes Agricultural Stewardship Initiative, funded through the Canada-Ontario initiative Growing Forward 2. This four-year initiative produced significant results for projects in Lake Erie and the southeast shores of Lake Huron, including:

- a total of $30.6 million invested — $10 million government and $20.6 million from farmers and custom applicators

- 1,300 environmental improvement projects on farms and 214 improvement projects for custom applicators of agricultural nutrients

- 850 Farmland Health Check-Ups, developed by farmers working one-on-one with participating technical experts

- establishment of six monitoring sites by conservation authorities to collect information on implementation of agricultural best management practices and water quality to evaluate effectiveness of practices for removing phosphorus

- 12 education and outreach projects with selected organizations implementing local projects to increase awareness of soil health and water quality within the agricultural community

While efforts are province-wide, there is a specific focus on the Lake Erie and Lake Simcoe watersheds, due to local water quality concerns and the dominance of agriculture production in these regions. Under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership’s Lake Erie Agriculture Demonstrating Sustainability initiative, farmers work one-on-one with a participating certified crop advisor or professional agrologist to identify best management practices tailored to the specific needs of their operation. This helps to increase farmers’ awareness of field-specific risks and supports them with a plan and financial support to take up practices that improve soil health and water quality. Across the province, between 2018 and December 2021, Ontario farmers completed approximately 1,840 projects representing an investment of approximately $58.7 million in on-farm environmental improvements ($18.8 million in cost-share funding from Canada and Ontario, and $40.4 million in farmer cash contributions). These projects:

- reduce the risk of soil loss from agricultural land through implementation of best management practices including planting cover crops, planting windbreaks and buffer strips and implementing erosion control structures

- improve management of agricultural land through modifications to tillage equipment to reduce soil disturbance and soil and nutrient losses

- improve placement of agricultural nutrients through modifications to equipment to reduce loss of nutrients from agricultural land

In addition, in 2021, Ontario created a new regulation under the Drainage Act to simplify processes for minor improvement projects that do not increase the risk of erosion, do not occur within existing wetlands, and do not enclose a drain. This update is expected to reduce costs and the time required for municipal authorization for some drainage projects that may include environmental benefits such as grassed waterways, sediment traps, and natural channel design features, which can improve water quality and reduce the frequency of floods.

Management of water usage and adaptation to lake level changes

The strategy makes five commitments to improve water quantity management, including working with the International Joint Commission (IJC) on managing lake levels, and assessing Ontario’s approach to manage water takings. As part of managing lake levels, Ontario continues to participate on the IJCs Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Adaptive Management Committee, which undertakes monitoring and technical assessments to support the on-going regulation of water levels and flows. This work is coordinated annually within a multi-agency and binational adaptive management framework. Ontario contributes to elements of various priority research and monitoring activities identified by the committee, such as testing remote sensing products and geospatial data sets used to enhance detection of changes to the wetland vegetation of coastal areas of Lake Ontario and the Upper St. Lawrence River.

The strategy also commits to Ontario fulfilling its obligations under the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement (the Agreement) in cooperation with Quebec and the eight Great Lakes States. As part of its obligations, Ontario continues to report its water use data to the Great Lakes Regional Water Use database annually as well as submit an annual assessment of the provinces water conservation and efficiency programs to the Regional Body. In 2019, Ontario met its commitment to submit an every-five-year report on its water management program and also contributed to the development of a renewed Science Strategy which identifies priority actions for collaboration with regional partners in order to strengthen the scientific basis for sound water management decision-making under the Agreement.

To support assessment of the importance of groundwater systems for sustaining water quality and quantity in the Great Lakes and tributaries, approximately 26,000 square kilometers of aquifers within the Great Lakes Basin were recently mapped by the Ontario Geological Survey.

Ontario also took action in 2021 to strengthen protection of water resources by updating our framework for managing water takings in the province. Based on a comprehensive review of existing water taking policies, programs, science tools, and consultation with the public, stakeholders and Indigenous communities, the province made the following enhancements:

- required water bottling companies to have the support of their local host municipality before applying to the province for a permit for a new or increased groundwater taking

- established provincial priorities of water use that can guide decisions when there are competing demands for water

- put in place new, more adaptive approach for the ministry and water users to better assess and manage multiple water takings together in areas of the province where water sustainability is a concern in areas where water sustainability is a concern

- made water taking data that is reported to the province publicly available

To support the changes, the province provided new guidance on managing water takings in areas where water sustainability is a concern and where there are competing demands for water.

With these new rules and guidance in place, we can be confident that water resources in the province are protected by strong policies and managed sustainably for future generations.

Goal 3: Improving wetlands, beaches and coastal areas

The purpose of this goal is to protect and restore wetlands, beaches, shorelines and other coastal areas of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin. The strategy includes commitments to:

- ensure and promote clean, safe shores

- protect and restore wetlands

- restore priority areas, such as AOCs

- use planning and policy tools, as well as best management practices to protect and restore these important areas in the Basin

Ensuring and promoting clean, safe shores

The strategy commits Ontario to work with public health units to improve the way beach water safety is monitored and assessed. Ontario’s public beaches are monitored regularly throughout the summer by public health personnel to assess water quality for the safe enjoyment of users. They do this by looking for conditions that might be hazardous or could pollute the water to an extent that would make it unsafe.

Routine monitoring is accomplished through testing of the recreational water for bacteria at a level that helps to determine its suitability for public use. In 2018, Ontario updated the Recreational Water Protocol and the Operational Approaches for Recreational Water Guideline to provide direction to boards of health on the delivery of local, comprehensive recreational water programs. The guidance includes:

- annual assessments, surveillance, inspection, and reporting of testing results of public beaches

- investigation and response to complaints of adverse events at public beaches

- encouraging the safe use and operation of public beaches through public health education tools

If the test results indicate that beach water quality is poor, the public health unit will inform the public of the status of the beach using the most appropriate method(s) of communication. These may include issuing precautionary notices at the beach, posting recreational water test results on the public health unit website, media releases and other forms of outreach. The Blue Flag program is promoted by regional tourism organizations in the province, particularly in southwestern Ontario, where four of the 26 Blue Flag beaches in Canada are located.

Read the measuring progress section of this report to read more about how the quality of Ontario’s Great Lakes beaches compares to previous years.

Protecting and restoring wetlands

The conservation of wetlands is an important part of improving the resilience of natural landscapes across Ontario. Wetlands purify our air and water, protect biodiversity and natural heritage, provide recreational opportunities and support First Nations and Métis traditional practices.

The strategy commits Ontario to supporting partnerships and collaborations to conserve and restore wetlands across the Basin. Since the first progress report, Ontario has made significant investment in protection and restoration of wetlands. For example:

- In 2017, the province matched $650,000 in federal funding through the Clean Water and Wastewater Fund to provide Ducks Unlimited Canada with $1.3 million to create 75 new wetlands and restore 17 existing wetlands in the Lake Erie basin in order to capture agricultural runoff and ultimately reduce the amount of phosphorus entering Lake Erie.

- Between 2016 and 2021, Ontario invested $1.75 million in the Eastern Habitat Joint Venture partnership through collaboration with Ducks Unlimited Canada, who has leveraged this support to over $5.5 million dollars for the protection of over 3,800 acres of wetland habitat and 9,900 acres of upland habitat primarily located in the Great Lakes Basin, as well as enhancement of an additional 3,400 acres of wetland and 212 acres of associated upland habitat.

- In 2020, Ontario announced an investment of $30 million over 5 years for wetland restoration and enhancement through the Wetlands Conservation Partner Program. Year 1 included approximately 60 wetland restoration and enhancement projects by Ducks Unlimited Canada. For Year 2, the program expanded to include agreements with six conservation organizations. From the first two years of this program, over $12 million has been invested in about 180 wetlands projects, restoring and enhancing over 4,200 acres of wetlands across the province.

In addition, in 2020, Ontario Regulation 454/96 "Construction under the Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act" was amended to provide alternative, optional rules for wetland dam owners to repair existing low hazard wetland dams without obtaining approval if they meet the requirements in the regulation. This allows eligible dam owners to benefit from cost savings and regulatory relief for wetland dam repairs while supporting the continued management of Ontario’s wetlands.

Restoration of priority areas

The strategy identifies seven actions for addressing other coastal areas in the Great Lakes Basin, including collaboration with partners on initiatives to improve nearshore areas, addressing key challenges in AOCs, and continuing to implement the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan.

Addressing concerns in priority areas across the Great Lakes Basin continues through implementation of the COA as well as other location-specific protection plans. For example, through investment by Ontario, Canada and the City of Toronto, the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative (2000–2028) aims to generate a thriving waterfront that can be enjoyed for generations. This initiative will transform 800 hectares of brownfield lands into sustainable mixed-use communities, with 25% of the revitalized area dedicated to waterfront parks and public spaces.

Recent work includes the development of the Don River Mouth Naturalization and Port Lands Flood Protection Project. This project will reduce flooding risk by naturalization of the Don River mouth through creation of new river channel and coastal wetlands, and will help with completing actions necessary to delist the Toronto and Region Area of Concern. The revitalization of Toronto’s waterfront is the largest urban redevelopment project underway in North America and is one of the world’s largest waterfront revitalization efforts ever undertaken.

Areas of Concern

Another priority for Ontario is the restoration of locations in the Great Lakes that were identified as having experienced high levels of environmental degradation. These are called Areas of Concern (AOCs). Through the 1987 Protocol of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, 12 Canadian and 5 binational AOCs were identified.

To date, three Canadian AOCs have been delisted (Severn Sound, Collingwood Harbour, and Wheatley Harbour). Significant progress has been made in the restoration of the remaining Canadian and binational Great Lakes AOCs since the first progress report. For example, five Beneficial Use Impairments not impaired

in 2019 and one — Degradation of Phytoplankton or Zooplankton Populations — in 2020.

To learn more about how Ontario has made progress in cleaning up Great Lakes AOCs, read the measuring progress section at the end of this report. These online resources also provide more information about ongoing work in the remaining Canadian and binational AOCs:

- Bay of Quinte

- Detroit River

- Hamilton Harbour

- Jackfish Bay

- Niagara River

- Nipigon Bay

- Peninsula Harbour

- Port Hope

- St. Clair River

- St. Lawrence River

- St. Marys River

- Spanish Harbour

- Thunder Bay

- Toronto and Region

Lake Simcoe

Lake Simcoe (Zhooniyaang-zaaga’igan in the Anishinaabemowin language) and its watershed covers 3,400 square kilometers and is part of the Trent-Severn Waterway, which flows into Georgian Bay of Lake Huron. As an important component of the Great Lakes Basin, the strategy commits Ontario to continuing to implement the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan (LSPP). This includes ongoing monitoring of key environmental indicators, supporting research to better understand the stressors facing the lake, and identifying innovative solutions and encouraging their adoption through local partnerships. The Minister’s 10-Year Report on Lake Simcoe, released in July 2020, highlights some of the actions that the province and partners have taken to protect and restore Lake Simcoe, such as:

- restoration of more than 15 kilometres of degraded shorelines

- planting of more than 55,000 trees and shrubs

- creation and restoration of 120 hectares of wetlands

- 50% reduction in phosphorus loads from sewage treatment plants entering the lake

- plans developed for improved water and nutrient management on approximately 54,000 acres of cropland

Monitoring has shown that the amount of algae in Lake Simcoe has decreased over time, leading to improved water quality, which has remained stable through much of the watershed since the 2015 Five-Year Report. For the cold-water fish community, monitoring has shown that lake trout, lake whitefish, and cisco continue to successfully reproduce, although the wild populations of these species are dominated by only a few year classes (fish produced in the same year), and are at lower levels than historically. A legislated review of the LSPP began in 2019 and was publicly launched in December 2020, with significant engagement and consultation throughout 2021.

Planning, policies and best management practices

As committed in the strategy, Ontario has made progress in updating wetland data and mapping to support conservation efforts and assist municipal and shoreline planning. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry developed the Great Lakes Shoreline Ecosystem, a classification and mapping tool to enhance and update the inventory, mapping and classification of terrestrial and wetland shoreline ecosystems in the Great Lakes.

The tool uses existing data and a standardized methodology to identify and map Great Lakes shoreline ecosystems, including all coastal and inland wetlands. This can be used to track progress towards conservation targets, monitor ecosystem change, assist municipal and shoreline planning, support conservation efforts such as habitat restoration and shoreline management, and improve our understanding of ecological processes.

Through updates to the Greenbelt Plan and A Place to Grow: A Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, municipalities are now required to consider the Great Lakes Strategy, the targets and goals of the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015 and any applicable Great Lakes agreements as part of watershed planning activities. These updates include provisions such as:

- integration of watershed planning approaches, taking into consideration the goals and objectives of improving, restoring and protecting the Great Lakes

- new policies to identify water resource systems and provide protection for key hydrologic areas such as significant groundwater recharge areas, highly vulnerable aquifers, and significant surface water contribution areas

In addition to the above, the update to the A Place to Grow: A Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe included a natural heritage system made up of natural heritage features and areas to provide connectivity and support natural processes.

Ontario is investing $12 million over three years (2021–2023) to support the Greenbelt Foundation’s ongoing work to help protect and restore the environmental and agricultural integrity of the Greenbelt area and enhance sustainable recreational and economic opportunities through several programs, including a grant funding program. Projects delivered through provincial funding will focus on three priority objectives: planting trees to increase natural cover, enhancing recreational opportunities for people to experience nature, and maintaining and enhancing green infrastructure and climate resilience. Examples of these projects include:

- enhancements to 1,200 kilometers of the Greenbelt to Lake Ontario waterfront cycling loop to increase recreational cycling and tourism, and contribute to Ontario’s rural economies with the expansion of six new connector routes

- advancing natural infrastructure in the Greenbelt by increasing natural cover by planting approximately 500,000 trees on private lands over two planting seasons

Goal 4: Protecting habitats and species

The purpose of this goal is to protect and restore the natural habitats, biodiversity and resilience of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin. The strategy includes actions to protect and restore species through tools such as habitat restoration, and reduce the introduction and spread of invasive species.

Protecting habitats and species

Assessing the status and improving our understanding of factors affecting the health of aquatic ecosystems, habitats, native species and food webs is a component of Goal 4 under the strategy. Protecting the habitats of the Great Lakes Basin and the plants and animals that live there can be a complex and challenging task, requiring dedicated research and monitoring to better understand relationships and impacts for effective management and protection.

Muskrat in the Great Lakes

A multi-year project by Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry determined that muskrat populations were very low in many Lake Ontario coastal wetlands and appeared to be influenced by lake-wide water level management in that basin. Future work will examine additional components of muskrat habitat, such as the type and density of vegetation and the presence of invasive species like Phragmitesand hybrid cattails. Muskrats provide a variety of ecosystem services in wetlands and their populations can serve as an indicator of wetland health. The results of this work will support the early evaluation of the International Joint Commission’s new water-level regime, and will provide greater knowledge of Great Lakes coastal habitats and ecosystems that is needed to protect these habitats and the species that reside within.

River-spawning Lake Trout populations

The strategy commits Ontario to continue the rehabilitation and maintenance of native Great Lakes species. Native populations of Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush) in the Great Lakes suffered catastrophic collapses in the mid-20th century due the impact of human activities as well as ecosystem stressors. Among the populations that collapsed were river-spawning Lake Trout populations that were known to swim up more than a dozen Lake Superior tributaries each fall.

As these populations collapsed, efforts by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry were made to preserve this unique type of Lake Trout in a chain of sanctuary lakes followed by years of stocking to restore the population. Ongoing work by Ontario since the 1970s has documented the successful restoration of a wild reproducing population spawning in the Dog River. The use of radio telemetry is providing information on the timing of spawning, and genetic analysis of eggs has confirmed the locations where spawning occurs, and the habitat preferred by spawning Trout.

Until recently, the Dog River was the only Lake Superior tributary known to have a spawning Lake Trout population. However, during an assessment of several eastern Lake Superior tributaries in the fall of 2021, Lake Trout in spawning condition were discovered in the Pukaskwa River potentially representing a second previously unknown river-spawning population. This positive discovery is a welcome success in Ontario’s continued work to protect and restore the species of the Great Lakes.

Fish behaviour and movement

In addition, Ontario has undertaken work to better understand the behaviour and movements of various fish species to support fisheries management and restoration efforts using the Great Lakes Acoustic Telemetry Observation System. In Lake Ontario, Ontario and academic partners have tracked tagged Lake Whitefish, Cisco, and Bloater in eastern Lake Ontario, revealing the behavior and seasonal movements of these fish. The use of acoustic receivers in Lake Superior’s Black Bay from 2016 to 2021 is providing information on Walleye migratory behaviour and location and timing of spawning, particularly in important spawning tributaries.

Ontario continued ongoing projects to track movements of Walleye in the Grand River, Lake Whitefish in Lake Erie, and Muskellunge in Lake St. Clair. New tracking projects were also undertaken for Walleye in the Thames River, Burbot in the east basin of Lake Erie, as well as expansion of the tracking area in Lake Erie’s east basin, the Thames and Grand Rivers, and Lake St. Clair.

Greenlands Conservation Partnership

In 2021, Ontario invested $20 million over four years in the Greenlands Conservation Partnership to help secure land of ecological importance and promote healthy, natural spaces. The funding will enable the Nature Conservancy of Canada and the Ontario Land Trust Alliance to conserve, restore and manage natural areas such as wetlands, grasslands and forests. This initiative will help mitigate the effects of climate change and increase the number of conserved natural spaces for the public to enjoy. Some key areas that have been secured with contributions from Greenlands funding include Michael’s Bay and Vidal Bay on Manitoulin Island, Brighton Wetlands, Alfred Bog near Ottawa and the Auzins Nature Sanctuary near London.

Protected areas

Ontario has published a series of indicator reports on the state of Ontario’s protected areas, and continued reporting on the general state of the environment, resource management and landscape planning. In 2020, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry and Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks completed technical work for a data set of information on all natural heritage and protected areas in Ontario, including the Great Lakes. Protection of Ontario’s natural heritage and biodiversity conservation is also supported by reporting sightings of animals and plants of conservation concern, wildlife concentration areas, plant communities, and natural areas in Ontario to the Natural Heritage Information Centre.

Through Ontario’s Greenlands Conservation Partnership, the Nature Conservancy of Canada and the Province have delivered 31 key conservation projects and protected over 164,200 hectares of lands and waters across Ontario. These protected areas will remain a home for wildlife, a haven for recreation, and a vital resource that cleans our air and water, while protecting communities against the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss. We sincerely appreciate the work that has led to this important investment for all Ontarians.

Mike HendrenRegional Vice President, Ontario Nature Conservancy of Canada

Read the measuring progress section of this report to read more about how Ontario has made progress in protecting habitats and native species.

Taking action on invasive species

Ontario is strengthening its efforts to protect the province’s natural environment and economy from the threat of invasive species. On January 1, 2022, new rules for 13 invasive species and watercraft as a carrier of invasive species came into effect. The new invasive species regulations add five additional aquatic invasive species:

- Tench

- Marmorkreb

- New Zealand Mud Snail

- European Frog-bit

- Yellow Floating Heart

Ontario has now regulated all 21 species included in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors Premier’s list of Least Wanted Aquatic Invasive Species, helping to protect the shared ecosystems and economies in the Great Lakes Basin. The regulation of overland transport of watercraft, is the first regulation of its kind, in Ontario and will help prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species within the Great Lakes as well as to inland waters in the province.

One commitment in the strategy is to develop scientifically defensible surveillance activities in areas at high risk of invasive species introductions. Ontario is continuing early detection and response actions for high-risk invasive species to prevent their spread to new waters and impacts to biodiversity and the provincial economy.

For example, community Environmental eDNA testing at sentinel sites across the Great Lakes allows for early detection of invasive species that are not currently being looked for and will potentially enable rapid responses before they can become established. Initial studies using this technique have detected aquatic invasive species in waters flowing into or adjoining the Great Lakes, such as Rudd in the Grand River. Sites across the Great Lakes that have been identified as potential entry points for invasive species will be seasonally sampled to develop an eDNA

metabarcode

, or a baseline characterization of the community of fish and other aquatic organisms present at that point in time. Comparison of the eDNA metabarcode at a location from one time period to the next will enable early detection of not only known aquatic invasive species, but also others that are not currently known to be in the Great Lakes Basin.

Other actions on invasive species include:

- In 2020, Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources, and Forestry developed prevention and response Plans for European water chestnut and water soldier, which are prohibited species under the Invasive Species Act, 2015.

- Ontario worked with Parks Canada Agency, the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters, Ducks Unlimited Canada and other partners to control water soldier in the Trent Severn Waterway, and European water chestnut in the Rideau Canal and in Lake Ontario, and at the Welland River. Rapid response efforts led by Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters were also undertaken at Red Horse Lake (in the Gananoque River watershed of the St. Lawrence River).

- Ontario and Canada continue to conduct surveillance for invasive carps within high priority areas within the Great Lakes including Lake Erie, and Lake St. Clair, utilizing techniques such as environmental DNA.

Read the measuring progress section of this report to read more about how Ontario has made progress in reducing the threat of aquatic invasive species to the Great Lakes.

Goal 5: Enhancing understanding and adaptation